Walter Valentini: the modern poetry of geometry

There is an ancient, classical and solemn mood that animates the works of Walter Valentini (Pergola, 1928). An Urbino-born artist and Milanese by adoption, like Donato Bramante. An artist accustomed to daily stepping through the doors of the Ducal Palace of Urbino in his youth, in that wing where the local School of Books was located. An artist therefore accustomed, from his earliest days, to meditating on the works of Luciano Laurana, Piero della Francesca, Francesco di Giorgio Martini, and all those magnificent artisans who made the Renaissance of the Marche town great. Observing Valentini’s works, one breathes in the rigor of Laurana, observes the eclecticism of Francesco di Giorgio, gets lost in the mathematical abstractions of Fra’ Luca Pacioli, and slips into the perspective constructions of Piero. And Valentini, like a Renaissance artist, is driven by a constant eagerness to experiment. There is no technique with which he has not tried his hand: panels, canvases, paper, engravings, sculptures “by porre” in terracotta, bronze, aluminum, glass, without of course neglecting those artist’s books that represent a considerable strand of his production.

And again, like the Renaissance artists, Walter Valentini aspires to the universal. His works are marked by a strong personal imprint although the artist’s ego seems almost to hide behind his arcane geometric, mathematical and spatial machinations, they go beyond mere contingency by losing contact with precise and defined spatial-temporal dimensions, they speak a lofty language and at the same time urge meditation, they start from the history of art but they also know how to explore new paths, questioning everything that has been conquered so far. For these reasons, that Renaissance alluded to just above represents but a point of departure: it would be reductive to anchor Walter Valentini’s production to the Urbino Quattrocento, however rooted in those experiences it may be said to be. There is, in Valentini, an extraordinarily modern tension.

One senses this from the moment one crosses the threshold of his latest solo exhibition, Walter Valentini. The Rigor of Geometry, the Fractures of Art 1973 - 2017, under way at CAMeC in Spezia and curated by Marzia Ratti. Welcoming the visitor, in the first room, is a work, Tempo fermo IV, which introduces the early research of the 1970s: geometric forms on a black field, immutable, fixed and eternal refer to the reflections on time of metaphysical painting with which Valentini was inevitably confronted. Deep silences, constructions that look like architecture, shadows that stretch over the elements. There is, in these forms, the sense of De Chirico’s art: the work transcends time by stopping in a motionless instant, the composition appropriates its typical tools such as geometry and perspective foreshortenings, Valentini’s language resembles De Chirico’s “dream-writing,” of which Ardengo Soffici had spoken in an article published in Lacerba in 1914, praising the way the great Ferrara painter had arrived at, “by means of almost infinite fugues darchi and facades, of great direct lines, of immense masses of simple colors, of almost funereal lights and darks,” to express “that sense of vastness, solitude, dimmobility, stasis that sometimes produce certain spectacles reflected in the state of memory in our almost sleeping soul.” The substratum, moreover, is common: if Soffici himself compared De Chirico to Paolo Uccello, another artist capable of an extraordinary, intense, modern and unique “writing of dreams,” Valentini, for his part, celebrates the great Renaissance artist with a Homage to Paolo Uccello that, through a triptych of geometric studies that have the same figure as their subject, almost seems to evoke the Florentine painter’s obsessions with perspective.

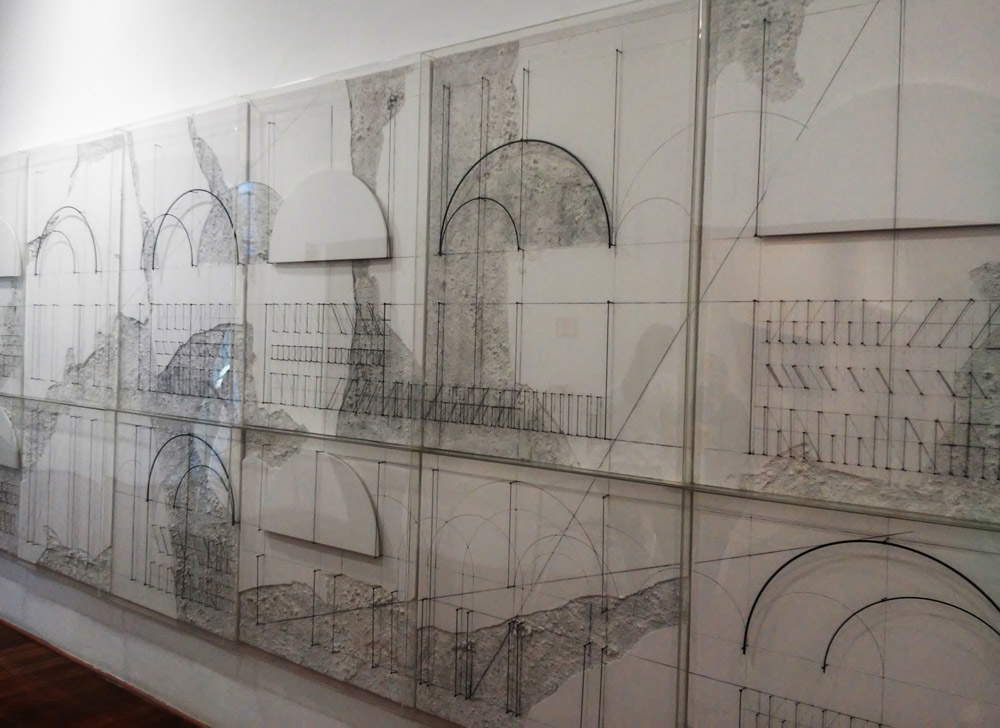

The next decade in the exhibition is represented by the enormous Stanza del tempo, which introduces those new investigations by Walter Valentini that, in certain forms, persist to the present day. The link with the Urbino tradition remains solid and manifest: Valentini, here, makes use of the new medium of lead or black cotton thread which, stretched over swarms of pegs fixed on the support, regulates and accentuates the proportions of the elements that give life to the composition. Still pure geometric forms that seem to give rise to fantastic architectures: in those arches that dominate the compositions, one almost seems to see the loggia of the Ducal Palace of Urbino, one comes into close contact with that “rhythmic musicality” of Walter Valentini’s visual worlds, as per the curator’s timely definition, one perceives how strong is the culture of rigor, balance, and harmony that animates the production of this refined artist. But there is also more: in The Room of Time, the succession of events, which has become the absolute protagonist “in its becoming, in its marking and corroding of things, in its re-proposing the hope of new spaces in which to live, new skies to scrutinize, new times to measure” (so wrote Roberto Budassi in 2006, quoted in the catalog by Gian Carlo Torre) introduces a contrast, a profound and perhaps even irresolvable disagreement between the rational order that man seeks in the cosmos and attempts to make manifest through his own constructions, and the destructive power of time that assaults matter by wounding and lacerating it. Valentini shows himself to be an original artist attentive to the research of Spatialism, Alberto Burri and those who, in earlier years, had posed the problem of time in art. But spatialism also fascinates Valentini in his attempt to overcome the two-dimensionality of the pictorial support: an attempt that was successful precisely with La stanza del tempo.

|

| Entrance to the Walter Valentini exhibition at CAMeC |

|

| A room of the exhibition |

|

| A room of the exhibition |

|

| Walter Valentini, Tempo Fermo IV (1974; charcoal and tempera on canvas, 150 x 150 cm) |

|

| Walter Valentini, The Time Room (1982; mixed media on panel, 200 x 540 cm) |

This suffered disagreement, which contains the essence of the human condition, made as it is of opposites and continuous contradictions, will no longer abandon Walter Valentini’s art, and will increase its contemplative dimension, because the gap between rationality (with all that it entails in terms of aspirations, desires, ambitions: see in this regard the works of the series La città del sole, a clear homage to the utopia of Tommaso Campanella) and the inevitability of time generates a crisis that, according to Enzo Di Martino, is “deliberately sought in order to arrive not at a simple work made to art, but rather to directly experience, and therefore propose to the concerning, an inalienable poetic event.” in other words, Valentini, meanwhile, continually questions that order that belongs to a past “which he well knows is unrepeatable,” unleashing almost a neoclassical artist’s attitude, and then reveals anunderlying restlessness that suggests how the apparent meanings of the work, with its rigorous proportions and balances, are somehow abandoned, denied in order to leave the viewer with new spaces for reflection. It is a way of doing things that has many traits in common with poetry and which, for that reason, becomes quite dense and lyrical in Valentini. “Even with geometry you can make poetry,” the artist reiterated. And with a simple gesture, with a sign, with a proportion, with a taut thread, Valentini is able to open glimpses of the universe, to take us back to remote eras, to guide us into intimate reflections on our existence. It is perhaps in this ability that much of the meaning of his art lies.

The viewer is guided in these meditations by strongly evocative titles, which make constant reference to time, the sky, and the stars. The La Spezia exhibition brings together a large part of these works, in which the golden section often recurs in the search for proportion among the elements that populate the compositions, where tributes to Renaissance artists are not uncommon (we have just seenHomage to Paolo Uccello, but it is also worth mentioningHomage to Raphael: a complex composition that takes up the geometries and perspective directions of the frescoes of the Stanza dell’Incendio di Borgo; in particular, one almost seems to see a geometric analysis of the scene of the Battle of Ostia) or to literature (magnificent is the triptych Inferno, Purgatorio e Paradiso that sets itself the seemingly paradoxical goal of giving rational and balanced interpretation of Dante’s cosmology), where an attempt is made to grasp the ineffable, where the infinite and the finite (and not finite) coexist. Surfaces on which complex orbits find space that seem to approach, sometimes looming, architectural elements such as the usual round arches, as if to demonstrate that man’s activities are influenced by those of the sky (so one might think when observing a work as complex as The House of Heaven). And then, those “graphic tracings” that, Mario Botta writes, seem “put in place to respond to verifications of complex mathematical calculations that require appropriate skills,” “geometric schemes made of images that master the composition of the work with hierarchies and proportions designed for individual themes.”

|

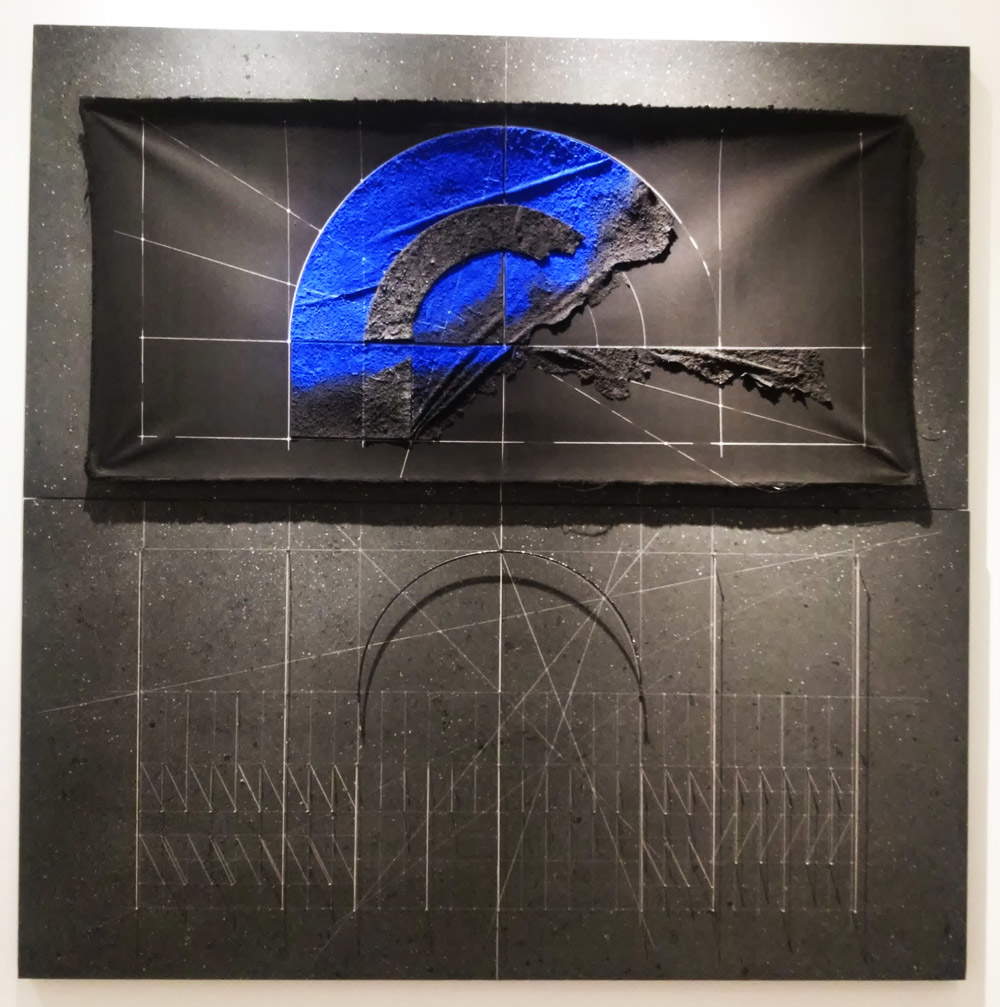

| Walter Valentini, The City of the Sun (1986; mixed media on panel and canvas, 200 x 200 cm) |

|

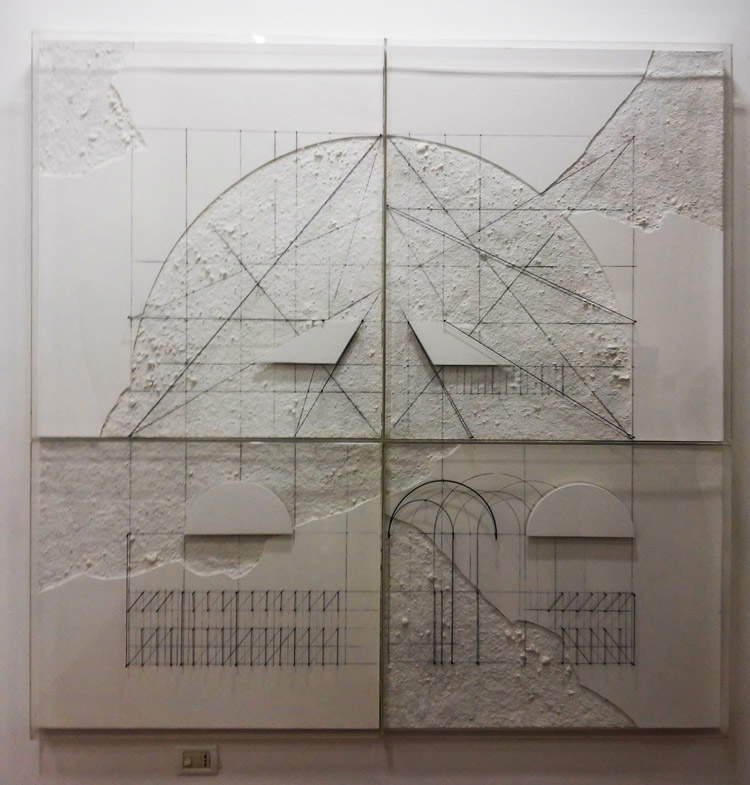

| Walter Valentini, Homage to Raphael (1984; mixed media on panel, 195 x 195 cm) |

|

| Walter Valentini, The House of Heaven (2008; mixed media on panel with gold leaf intervention, 200 x 500 cm) |

|

| Walter Valentini, Inferno, Purgatory and Paradise (1988-1991; mixed media on Duchêne paper, 86 x 62 cm) |

Deserving a separate discussion are the splendid sculptures for which Walter Valentini, even in his constant experimentalism that has led him, over the course of his long career, to try various solutions, prefers two materials: bronze and terracotta. The bronze sculptures, where the orbital ellipses typical of works on paper and canvas return, are animated by a vertical momentum that, added to the artist’s owngeometric abstraction, makes his debts to Russian constructivism even more evident. The Measures, the Sky is a work, in this sense, particularly significant: a half bronze disc crossed by a gnomon that makes it therefore similar to a sundial (symbolizing the dimension of time) and bearing imprinted on its surface signs that evoke orbits and constellations ( space, but also movement). And how can one remain indifferent to the Golden Gate, a small bronze sculpture that, in the exhibition layout, has been placed exactly opposite the large monochromatic composition Zeta 3, so that the semicircle on the top, when viewed from a certain point of view, in perspective ends up matching exactly the homologous forms of the work on canvas?

Terracottas, then, are works whose process that determines their creation is particularly consonant with the spirit of the artist, precisely because there is always a component of unpredictability in the creation of terracotta: “to fully understand the value of a creative work conducted according to the rules of ceramic art, but subjected to the accidentality of the unexpected, which is always present in the alchemical procedures that change the physiognomy and consistency of the plastic material treated,” writes Roberto Budassi, “we must also assess the unpredictability of the firing controlled by fire, which in the kiln forges the earth like metal in Vulcan’s forge. [...] Firing at very high temperatures, almost fusion-like, where it is fire that decides the fate of a rebirth of the artifact or definitively causes its death, its destruction.” Valentini’s terracottas are perhaps his work most prone to evoke a sense of antiquity: rough, sandy, burnt, they almost seem like artifacts from distant civilizations, and even the name of the Tabulae series hints at the waxed tablets on which the ancient Romans wrote with a stylus.

|

| Walter Valentini, The Measures, the Sky (2002; polished and patinated bronze casting, white marble base, 97 x 78 x 45 cm) |

|

| Walter Valentini, The Golden Door (2010; cast in polished and patinated bronze, 88 x 52 x 30 cm) |

|

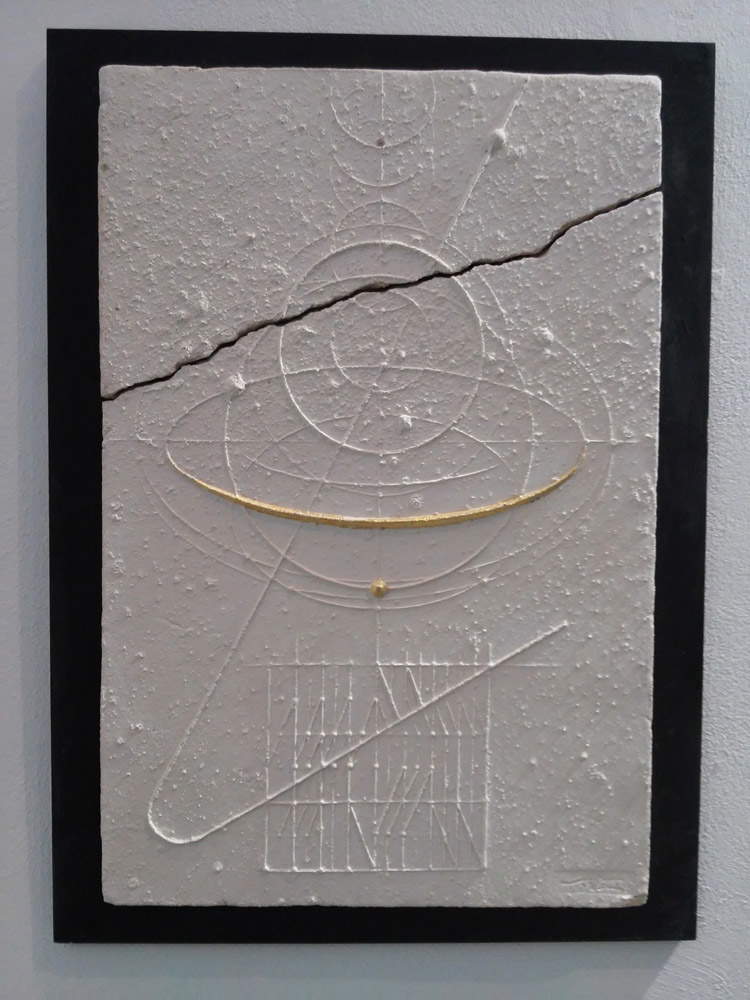

| Walter Valentini, Tabula II (2016; refractory terracotta with gold leaf intervention, 67 x 45 cm) |

CAMeC presents its audience with an exhibition of great quality, a comprehensive retrospective on an interesting master of contemporary art, educated, refined and versatile, who has worked in contact with the greatest masters and exhibited in the most prestigious contexts, including the Venice Biennale. As is typical of the La Spezia museum’s monographs, this one also traces the artist’s entire career, exploring every aspect of his production, with an organization that follows, fundamentally, a chronological line but also manages to depart from it in order to delve into certain themes (special rooms are devoted, for example, to terracottas, graphics and artists’ books). The catalog, sober and essential, with a very rich iconographic apparatus, contains five essays to better probe the depths of Walter Valentini’s art: of particular note are the opening one by the curator and the two that deal with terracottas and artist’s books, by Roberto Budassi and Gian Carlo Torre, respectively.

Finally, it is worth noting that, with more than one hundred works on display, the CAMeC anthological exhibition is the most comprehensive survey of Walter Valentini’s works ever seen. And it is worth concluding with some verses that, a few years ago, poet Eugenio De Signoribus dedicated to his fellow countryman artist: they describe with synthesis and lyricism the highest essence of Walter Valentini’s art. “You raised to the sky / Your gaze and there scrutinized / Its secret plots.... / Your geometric clarity / Brought them into view / With natural harmony... / Now they are charts and measures / For a celestial navigation / Lines that conquer the dark / And never precipitate / Behold, in the face of evil / Your ideal city / Is a fortress in the cosmos / The map of your infinity / Offers to the reclusive gaze / The grace of a pure sign / No wall you leap / No eternity you touch / Without a seed of light!”

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.