Vera Lutter, unique photographs that make the real ambiguous. What the exhibition at MAST in Bologna looks like.

That the aura of the work of art no longer derives from its uniqueness is a fact that has been acknowledged ever since Walter Benjamin, at the turn of the two world wars, published the famous essay The Work of Art in the Age of its Technical Reproducibility technique, in whose introduction he pointed out how the new technologies for producing, reproducing, and disseminating art on a mass level had radically changed the artistic experience both from the point of view of creation and fruition. Chiefly responsible for the invalidation of the sense of the distinction between original and copy was photography, whose uncanny effect depends, despite all the manipulations to which it is liable, on its innate relationship to visual evidence, a concept we instinctively tend to equate with a kind of “proof” (in English “evidence”) of the existence of something. A photograph, no matter how programmatically adulterated, blurred, mendacious or abstract it may be, is always the imprint of a presence endowed with its own inescapable reality, even when it does not coincide with the sense and truth of the image that renders (even with sectarian or imaginative intent) a particular aspect of it. And it is precisely this continuous coming and going of the mind and the gaze between what the author wants to show in his shot and our personal archive of already metabolized images that makes us dwell on a photograph in order to decode its elements and then assign to their whole that specific degree of trustworthiness that they call into question in fiction as in relevance to reality. The primacy of sight as the arbiter of our judgment is still more alive than ever in the disorientation generated by hyper-communication, despite the fact that the uncontrollable quantity of images conveyed by the Net, many of which can no longer be defined as photographs because they are automatically generated without starting from a real referent, seems to definitively sanction their unfoundedness.

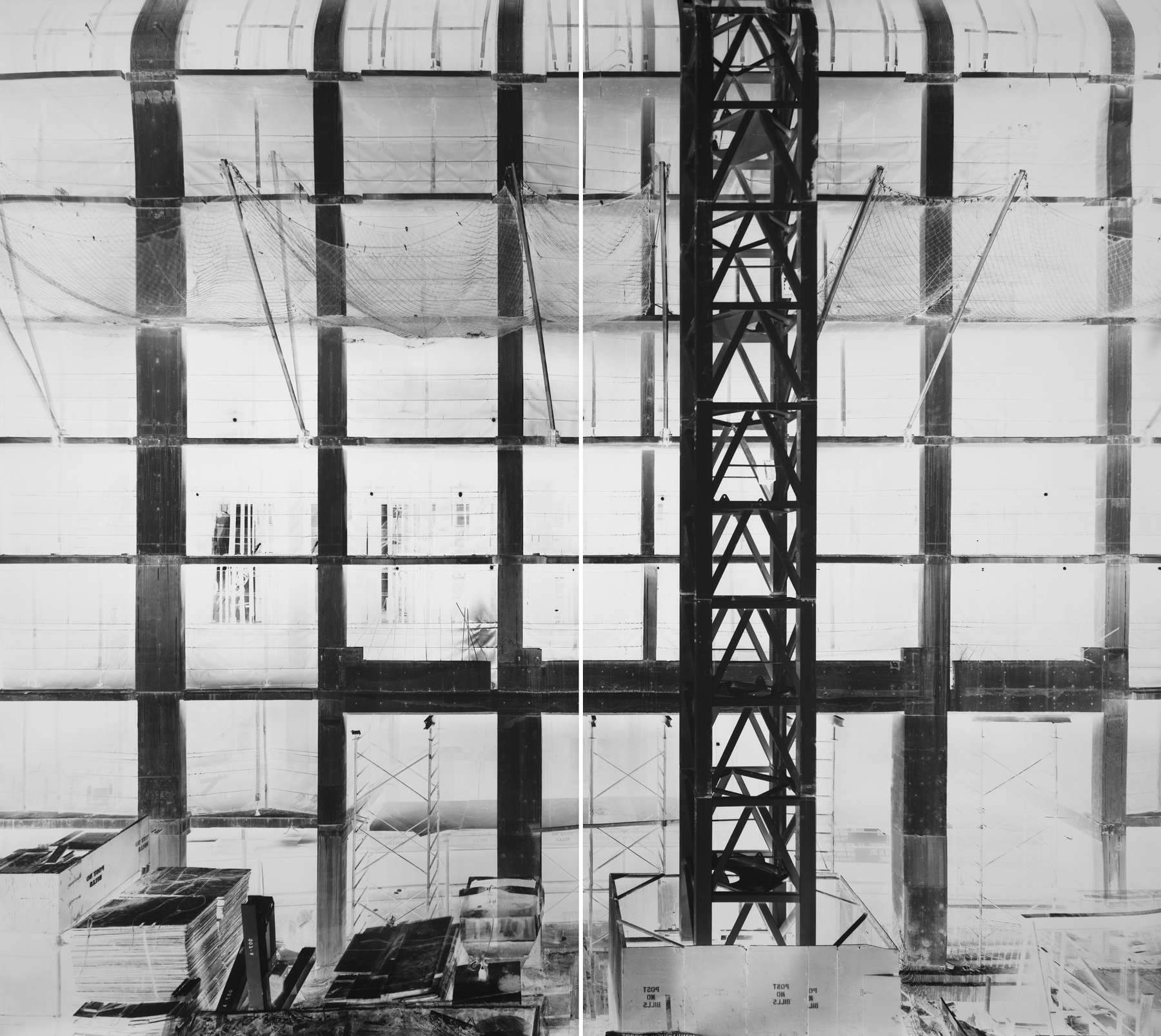

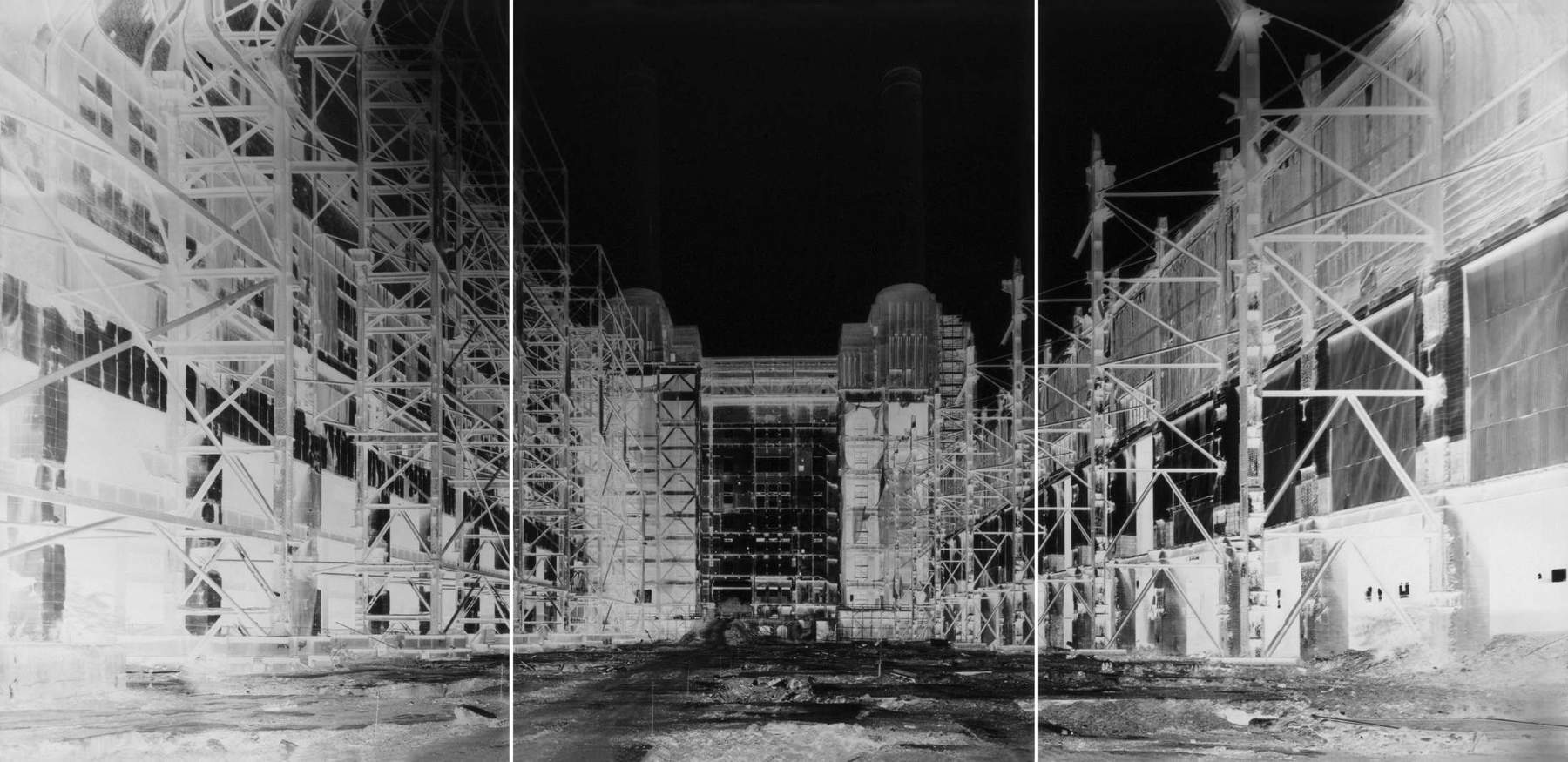

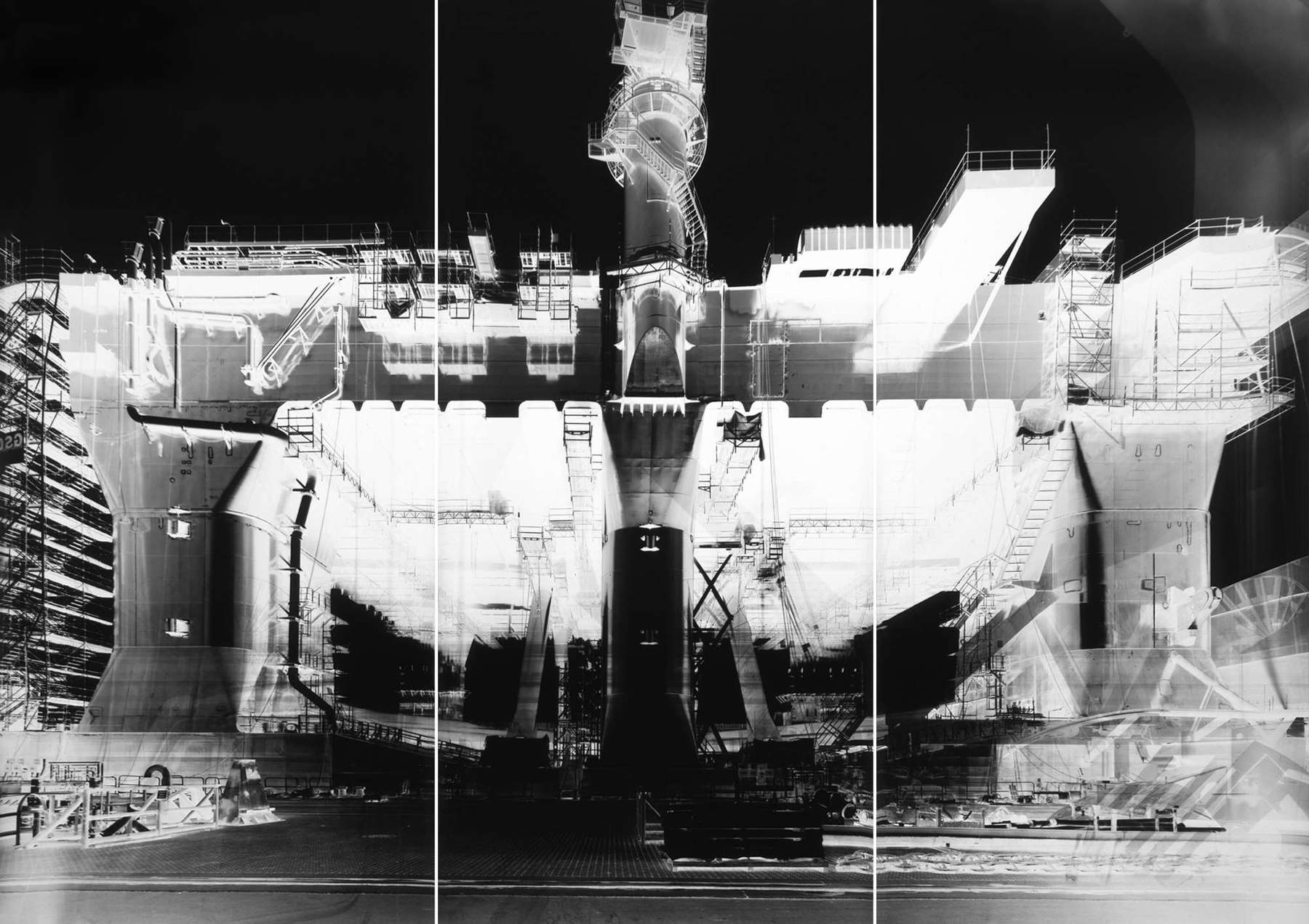

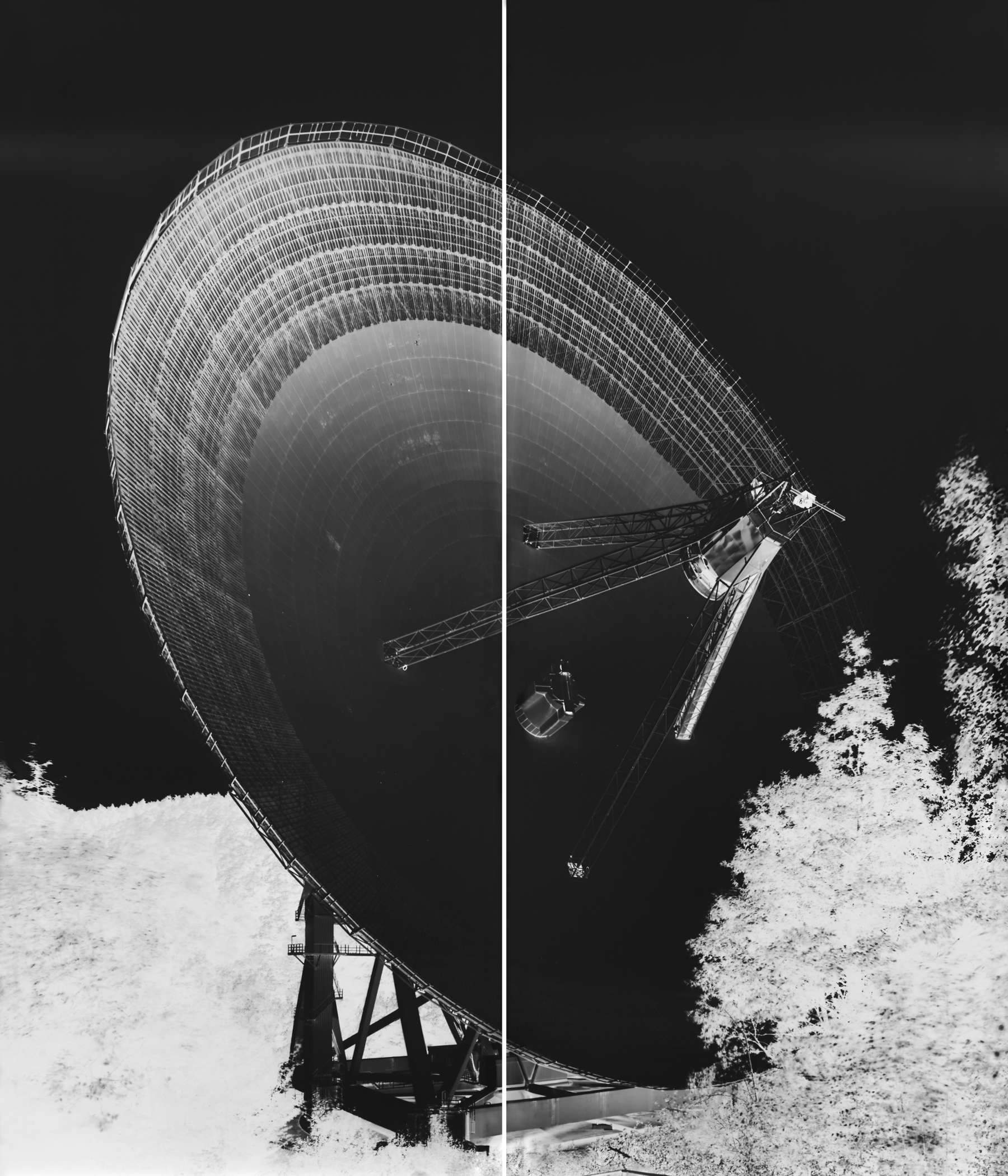

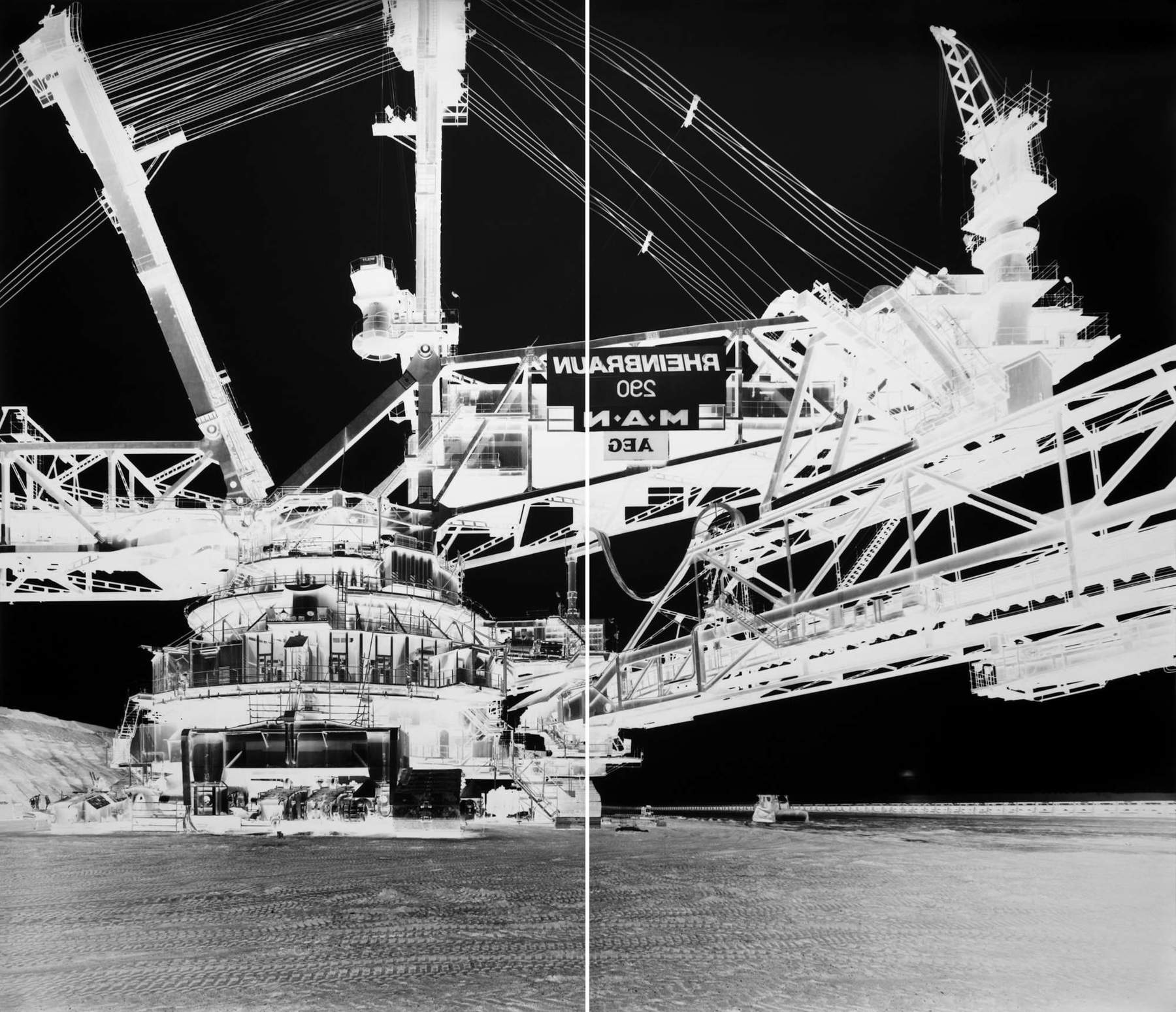

Placing itself in an interesting dialectical relationship to these issues is the work of photographer Vera Lutter (Kaiserslautern, 1960; lives and works in New York), who in her exhibition Spectacular, currently on view at the Fondazione MAST - Manifattura di Arti, Sperimentazione e Tecnologia in Bologna, presents twenty large-scale works made from the 1990s to the present and focused on the themes of industry, labor and transportation infrastructure. The uniqueness of the artist (represented in Italy by the Alfonso Artiaco gallery and abroad by giants of the caliber of Gagosian, Baldwin Gallery and Galerie Max Hetzler) lies first and foremost in the particular technique she uses, at the origin of the unmistakable aesthetic character of the large, x-ray-like black-and-white images with which her signature has been associated for thirty years. Instead of using an ordinary camera, the artist realizes her shots through optical chambers that she conceives as real inhabitable rooms, inside which a thin beam of light coming from a single hole placed on the wall facing the subject projects on the opposite one, covered with photosensitive paper, the upside-down and inverted image of what is outside. The silver salt-based emulsion with which the paper is coated darkens in areas where it is reached by light: all the bright elements of the real landscape, then, such as the sky or reflective surfaces, turn black on the paper, while those that are dark in reality because they tend to absorb light, such as tree canopies or the metal pylons of construction scaffolding, appear as white traces because they only laboriously impress the paper.

Exposure times are very prolonged and, depending on ambient light conditions and pinhole size, can range from several hours to months. This process, which is extremely elaborate in the preparatory operations of building and positioning the darkroom, is as reflective and prolonged in the shooting phase as it is unrelenting and instantaneous in the developing phase. Nothing is conceded to post-production: at the end of the exposure, the artist rolls up the impressed paper in a special container to protect it from the light and transfers it to her laboratory for the revealing and fixing of the image. The result of this process, unknown to herself until the work is completed, is a single paper negative of which the right-left and light-dark inversion is maintained, while a simple 180-degree rotation from the shooting position eliminates the upside-down tilt from fruition. The dimensions of the prints are dictated by those of the room to which the photosensitive papers were affixed, and in those with an environmental vocation like most of the works exhibited at MAST, structurally similar to polyptychs, compositions of several sheets make up for the absence in the market of formats wider than 1, 45 meters.

The artist recounts that she began adopting this procedure in the 1990s when, in the midst of the conceptual temperament, after studying sculpture at the Akademie der bildenden Künste in Munich, she moved to New York to attend the School of Visual Arts. Inspired by the new architectural and environmental context, very different from that of European cities, she decided to transform the entire room of the 27th-floor loft where she lived into a pinhole camera to record the changes in the landscape (a parking lot gradually replaced by a building) she saw through the window. For two years he documented the construction site with this pre-photographic tool, which calls into question both the optical chambers popular among Vedutist painters since the Renaissance, in which theupside-down image of the chosen landscape was projected onto a surface first vertical then horizontal so that it could be copied onto a sheet of paper, as well as the first photographs in history, such as the heliograph on a tin plate View from the Window at Le Gras taken on August 19, 1826 by Nicéphore Niepce. Like Canaletto, who obtained his astonishing perspective views of Venice through this very technique, based on the same principle in the German artist’s panoramic images, every element appears perfectly in focus, despite the width of the frame and the oversizing of the prints. Moreover, like nineteenth-century daguerreotypes, her shots are also unique non-replicable pieces that, by invalidating the assumption of reproducibility as consubstantial to the essence of the photographic medium, restore the category of uniqueness in the aesthetic evaluations and quotations of her works.

Another exceedingly interesting aspect in his interpretation of this process is the ambiguous relationship he establishes with reality: while each shot is the outcome of an unmediated recording of the visible, the end result is never a representation of reality, but an ambiguous restitution of it, rendered indecipherable by the overlapping of the multiple temporal and spatial levels of the observed world in its synchronicity. The artist’s are always deserted settings (because paper is unable to impress dynamic events such as the passage of people and vehicles), predominantly urban, monumental and mysterious in their syntactic legibility, seemingly immobile in time but simultaneously teeming with concomitant happenings.

In these views based on alternating impenetrable blacks and diaphanous imprints of architectural objects, the contrast between the sharpness of the details and the surreality of the whole generates an exciting battleground between the universal and the particular, density and volatility, past and future, presence and absence, control and the unexpected. It is as if the most impermanent aspects of reality acquire a supernatural solemnity, while those designed to be imperishable exhibit the melancholy of their constitutive fragility. Seemingly aseptic objects such as mining plants, construction sites, disused industrial areas, hangars and means of transportation acquire a dreamlike spectacularity, where there is always something that does not add up and arouses suspicion. Sometimes the artist accentuates the alienating effect inherent in the technique being set up by placing mirrors in the pinhole’s field of view that multiply perspectives or even prints of other negative images of environmental dimensions (which, of course, being re-photographed, are subject to further inversion). In this maze of alterations the viewer’s gaze becomes confused and gives way to memory and mental representation, while the image absorbs him but at the same time repels him with its dazzling whites, never allowing him to delve into its mystery.

The exhibition at MAST provides a particularly happy setting for the proposed works, all of which focus on the imagery of technology, work and industry as per the programmatic intentions of the Bologna-based cultural institution, which was established in 2013 to experiment, including through photography, with new ways of business-community integration and constitutes a valuable opportunity to see “live” a broad and representative selection of the artist’s creative path, so far never the protagonist of a solo exhibition in an Italian institution.

Slightly missing (to the desire, not to the thematic rigor of the exhibition) is a mention of the iconic shots she took at some historical sites, such as Paestum, Venice, Rome or Athens, which it would have been intriguing to visually relate to the industrial or housing facilities on which the exhibition focuses in order to grasp continuity and differences in approach and rendering. The informative apparatus that supports the public in the correct reading of the works is effective, starting with guided tours and ending with the provision, outside the structure, of a darkroom similar to those built by the artist for his photographic sets. Upon entering this dark shed equipped with a pinhole and closing the door tightly, one will be able to see projected on the wall opposite the one from which the light enters a strip of upside-down city skyline, which will allow visitors to identify with Vera Lutter’s particular way of “inhabiting” the construction sites of her images. Immediately recognizable even in this reflected horizon is the reflective arch of “Reach,” a site-specific stainless steel sculpture created by British artist Anish Kapoor in 2017 and placed on the access ramp to the public part (consisting of a museum, a foyer and an auditorium) of the multifunctional complex that houses the corporate welfare services of the Coesia group of companies of which MAST is an emanation.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.