In conclusion to their essay published in the catalog of the major exhibition Paris Bordon. Pittore divino, set up at the Museo di Santa Caterina in Treviso until January 15, 2023, curators Simone Facchinetti, a researcher at the University of Salento, and Arturo Galansino, director of the Fondazione Palazzo Strozzi in Florence, emphasize that from their point of view "there was no need to give Paris a new position in the Venetian Renaissance, for the simple reason that he already occupied it by right." And they are keen to specify in the same essay that the current exhibition is in the wake of the initiatives that Paris Bordon ’s hometown (Treviso, 1500 - Venice, 1571) supported to celebrate its most illustrious painter, whom Venetian historiographer Marco Boschini called “Divin Pitor” (hence the title of the current retrospective): in 1900, for the four hundredth anniversary of Bordon’s birth, Luigi Bailo and Gerolamo Biscaro had initiated careful research and a series of studies with the intention of returning as much data on the painter’s life as possible; this was followed in 1984 by a monographic exhibition in the Palazzo dei Trecento and the following year by an international conference with the same objectives. The current monograph is thus intended to be an “exhibition designed for a wide audience,” complemented by a “specially written catalog in simple forms,” as explicitly stated by the curators, and consisting of “carefully selected works by Paris Bordon” from major European museums.

A laudable goal that of the curators, who have followed as a basic principle that of an exhibition aimed at everyone, told both in the exhibition spaces and in the catalog in a way that is understandable and suitable for the general public, in order to make people understand the variety and extraordinary quality of the artist’s production. Not an exhibition only for connoisseurs and scholars, but apopular exhibition: the exhibition itinerary is in fact divided into sections, eight to be exact, which take the visitor through Paris Bordon’s production, from his beginnings in Titian’s Venetian workshop (Bordon was in fact among his greatest pupils) to the genres and themes he tackled, such as portraits, paintings for private dev otion and large altarpieces for public devotion, but he also devoted great attention to themes such as mythology anderos. The public has an opportunity here to get to know Bordon’s art in its various aspects, as the largest monographic exhibition to date in Italy devoted to the painter from Treviso, as it has been called, offers the opportunity to see up close as many as thirty-five of the painter’s works , including paintings and drawings, from the most important museums in the world, such as the Alte Pinakothek in Munich, the Louvre, the National Gallery in London, the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna, the Muzeum Narodowe in Warsaw, the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford, the Musée des Beaux - Arts in Caen as far as abroad is concerned, and the Gallerie degli Uffizi, the Galleria Doria Pamphilj in Rome, the Pinacoteca Nazionale in Siena, the Musei di Strada Nuova in Genoa, the Ca’ d’Oro in Venice, the Accademia Carrara in Bergamo, the Pinacoteca “Corrado Giaquinto” in Bari and the Vatican Museums. It is a total immersion in Paris Bordon’s art that truly sets the pace among the initiatives aimed at getting to know the painter accomplished over the decades.

We start with a selection of paintings from the third decade of the 16th century, between 1518 and 1530, where we recognize the strong influence of Titian, at whose Venetian workshop Paris trained. We do not know of any works prior to this decade, so his earliest paintings date from when he had already left Titian’s workshop: on June 21, 1518, Bordon is in fact documented as “pictor habitator in Venetiis in contrada Sancti Iuliani,” thus already autonomous. Those on display are therefore works by an already trained painter, but Titian’s legacy is clearly visible especially in thehorizontal setting of the Holy Family in the painting in the Doria Pamphilj Gallery in Rome, comparable in composition to Titian’s Holy Family with a Shepherd in the National Gallery in London, not on display. More nonchalant and with an attempt at emancipation from the Titian setting, however, are the Glasgow panels, in which there is a glimpse of Jacopo Palma the Elder. One of these, The Madonna and Child, Saints Jerome and Anthony Abbot and a worshipper, is among the first paintings in which Paris signs himself Paris Bordon Tarvisinus, enhancing his own origin.

There follows a section devoted to Bordon’s critical fortune, beginning with Pietro Aretino , who wrote a letter in December 1548 comparing him to Raphael, and continuing with Vasari , who in his 1568 Lives traced a sort of description of Bordon as a continuation of Titian’s life, pointing to him as his only worthy heir. The description is the result of a meeting between Vasari and Bordon in the latter’s house in Venice’s contrada San Marcillian in May 1566. He describes him as a peaceful and simple man, far from intrigue; a man who led a secluded life, “fleeing competition and certain vain ambitions,” and a “most excellent musician.” Nearly a century after the Lives, it was Carlo Ridolfi’s Maraviglie dell’arte, in 1648, that described the painter: he devoted an entire profile to him, taking up Vasari’s information, and considered him the leader of an uneven array of painters originating or active in Treviso. In the early 19th century Abbot Luigi Lanzi described him in the third tome of his Storia pittorica as a man of wit and a painter of great originality, a pupil of Titian for a short time and then a fervent imitator of Giorgione. Giovan Battista Cavalcaselle ’s attention is instead shown through a series of drawings accompanied by annotations of some of Bordon’s famous paintings such as the Pala Manfron in the Galleria dell’Accademia in Lovere. Finally, in 1900, on the 400th anniversary of the painter’s birth, the aforementioned Luigi Bailo and Gerolamo Biscaro published the first modern monograph dedicated to him.

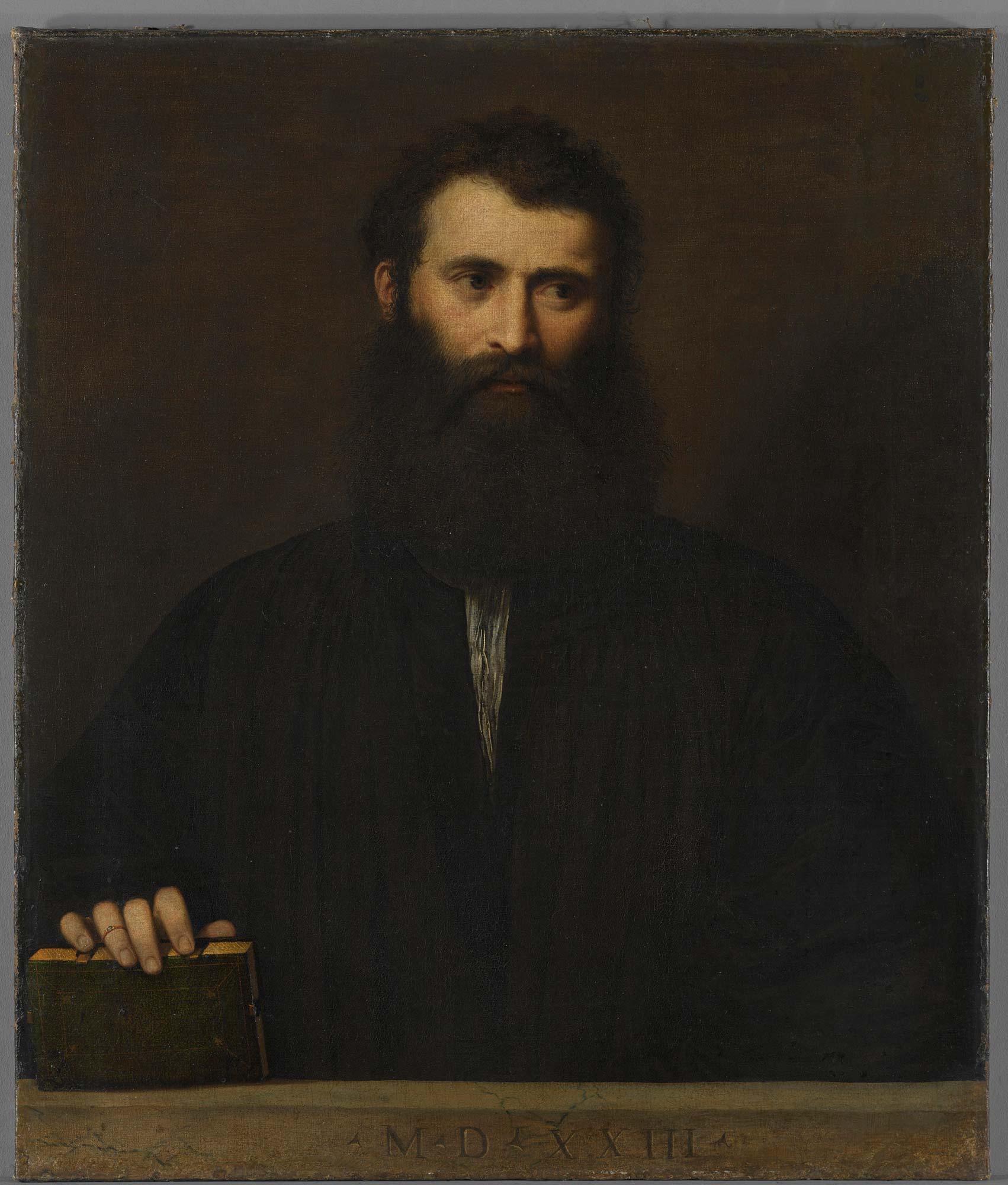

The exhibition tour continues with portraits, a genre widespread in 16th-century Venice, in which Paris Bordon was skilled. On display here are portraits of seven figures whose identities are, for the most part, unknown. Prominent among the five men depicted is the Portrait of a Gentleman from the Alte Pinakothek in Munich, which is the oldest portrait painted by the painter, dated 1523. The Portrait recalls those by Giorgione characterized by a veil of melancholy and strong psychological intensity, such as the Giustiniani Portrait from the Gemäldegalerie in Berlin. In fact, it seems that about ten years after Giorgione’s death from the plague in 1510, Bordon “set himself [...] in mind to want to per ogni modo seguitar[n]e la maniera,” as Vasari states. Prouder, however, are the portraits of Nikolaus Körbler, a merchant who became a nobleman at the behest of Charles V, the so-called Attaccabrighe, and Thomas Stahel, a merchant from Augsburg who played an important role in the city. The latter is identified by the initials T.S. and the family coat of arms on the column, while the name of Augsburg merchant Hieronymus Kraffter appears on the letter he is holding. The Gentleman of the Red Palace is also holding a letter: in this painting we see two consecutive moments between them at the same time. The noble gentleman in the foreground, with sleeves of garish red, holds the letter, which in a later moment, as seen in the sketch on the left, behind him, a woman will receive from a servant. With a similar composition, the young woman in the National Gallery is also waiting for news from the man seen among the architectural elements in the background. Luxuriously dressed and embellished with jewelry and pearls in her hair, all we are given to know about the young woman is her age: on the base of the column is in fact written “Aetatis suae / Ann. XVIIII.” Both paintings could refer to amorous relations, since the red dress was usually worn at weddings. However, if the Young Woman in the National Gallery in London has more real features, the Young Woman in the Kunsthistorisches Museum comes across as more idealized. In a domestic setting, the young woman is depicted with a shifty gaze, ethereal skin and long blond hair, between which she slips the fingers of her left hand, while with her right she holds open a small wooden box.

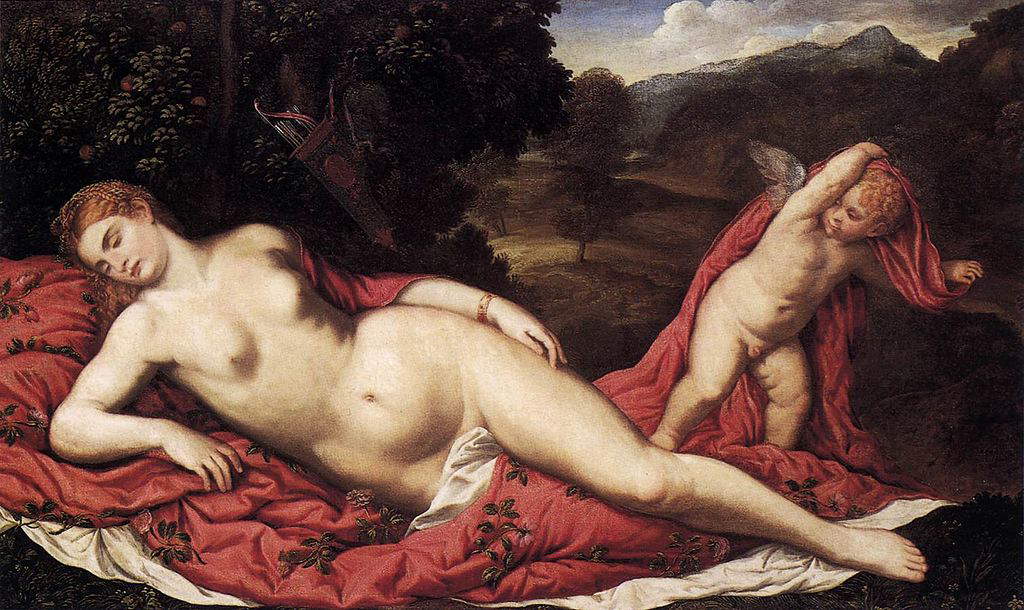

The next two sections are closely related because Paris Bordon’s paintings of mythological subjects often depict very sensual characters, especially the female figures. Examples are the Venus and Cupid in Warsaw and the one in the Ca’ d’Oro in Venice: the former close to the Venuses of Palma the Elder, the latter to those of Giorgione and Titian. That of the beautiful young maiden lying on a drape and completely naked immersed in a wooded landscape while her little son Cupid approaches her is, however, one of the most widespread secular subjects in Venetian art of the 16th century. They leave the breasts uncovered in Bordon’s sensual female figures, characterized by a mother-of-pearl complexion, long tawny hair and soft iridescent fabrics: Vasari recalls in his Lives of a painting “d’una donna lascivissima” sent by Bordon to Ottaviano Grimaldi. Although we do not know which painting Vasari was referring to, however, it is certainly a work similar to the Portrait of a Young Woman from a private collection displayed in the exhibition.

Sometimes more or less markedly lascivious portraits were made in marital contexts, such as the woman in the guise of Flora, a symbol of fertility and marital concord, in which the clothed but bare-breasted young woman rotates her torso slightly and raises her arm to pluck roses and then places them on a flap of her dress, which she holds up with her other hand. Even more explicitly related to the nuptial theme is the beautiful painting depicting Mars, Venus and Cupid crowned by Hymenaeus, a masterpiece in the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna, rich in amorous and erotic elements. In the center of the scene, Venus, with her breasts completely uncovered, is held in a tender embrace by Mars in armor; the two hold hands as they are crowned by the patron of the wedding rite Hymenaeus with wreaths of roses (a gesture also made by the Cupid in the Pair of Lovers in the National Gallery, London), and Cupid, after abandoning his quiver and bow, spills a basket of roses onto Venus’ belly. With her right hand, the goddess offers rose blossoms to Mars, which he is about to pluck, and with her left hand she plucks a quince from the tree, a symbol of love and fertility. A recent study, which began with the reconstruction of Jeremias Staininger’s collection, considers this large painting part of the secular-themed cycle made for Christoph Fugger, a patron of Augsburg. The Stainingersers were natives of Augsburg, and the list of their paintings includes six by Paris Bordon, some of which are now in the Kunsthistorisches Museum and coincide in both subject matter and format with those in the painting cycle.

Paris

Paris Paris Bordon,

Paris Bordon,

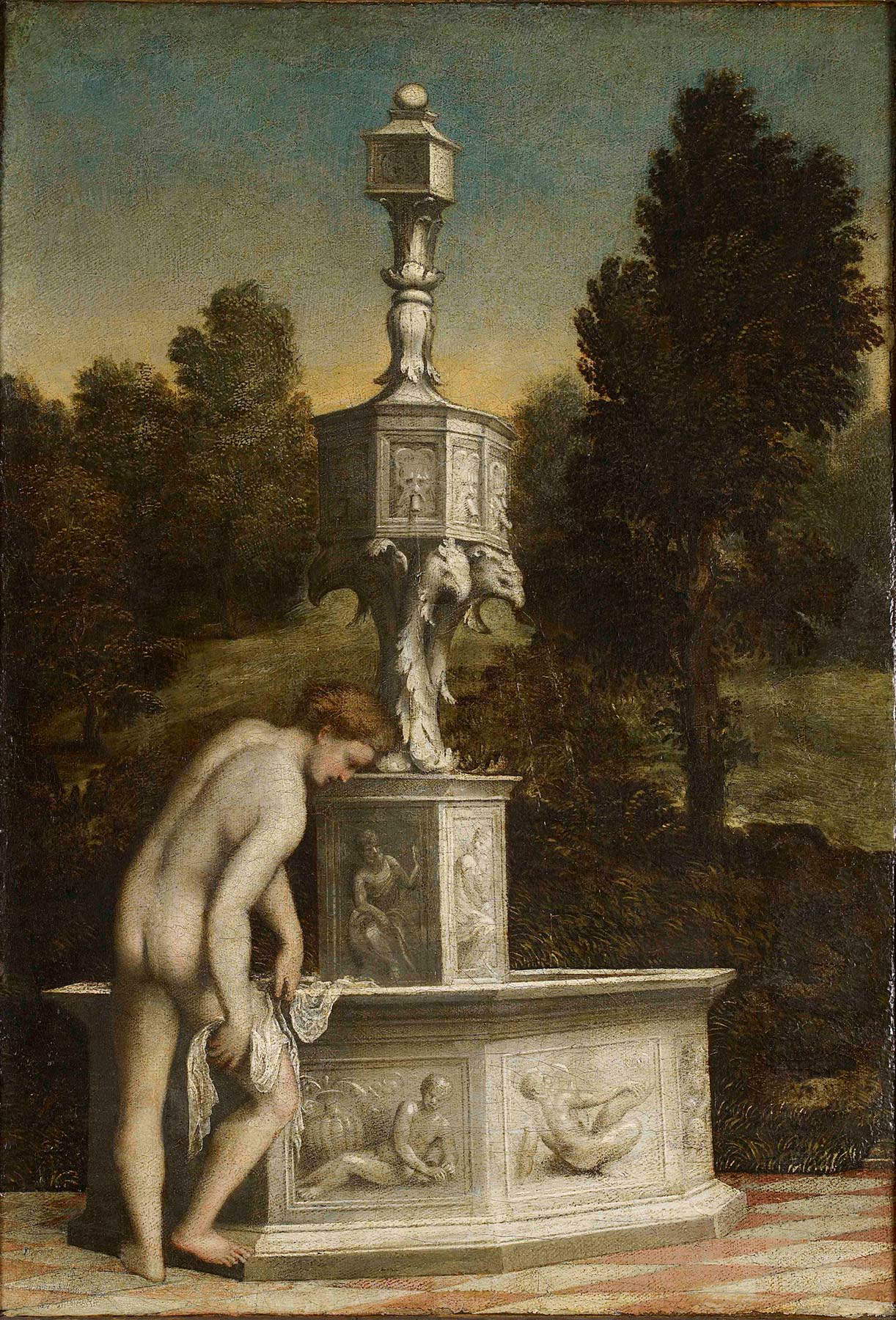

In the exhibition we then have the opportunity to admire some of the artist’s drawings that give insight into the careful study behind each image in his paintings. Venetian art has traditionally had little to do with drawing, unlike Florentine art, while it is very much tied to color: by contrast, a remarkable graphic corpus has come down to us of Paris Bordon; these are studies of an anatomy or a pose, studies focused on a single figure. The drawings on display come from the Louvre and the Prints and Drawings Cabinet of the Uffizi, and of particular note are, in addition to the Study for a Nude Man possibly referable to Christ in Limbo (of which the original is lost, but of which a copy is preserved in a private collection), the preparatory study for the Virgin of theAnnunciation in the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Caen, displayed at the end of the exhibition itinerary, and the preparatory study for a Bathsheba at the Bath, a frequent theme in Bordonian painting production, as evidenced by the painting on display at theAshmolean Museum inOxford in the section on Eros.

Approaching the conclusion of the monograph, the visitor is placed in front of devotional, private and public works: the former represented by the two examples of Christ the Redeemer from the Carrara Academy in Bergamo and the MAR in Ravenna, a very recurring iconography in Bordon’s production; the latter represented mainly by important altarpieces, such as the Pala Tanzi and the Pala Manfron. The Tanzi Alt arpiece, depicting the Madonna and Child Enthroned between Saints Henry of Uppsala and Anthony of Padua, is now kept at the “Corrado Giaquinto” Pinacoteca in Bari but comes from the chapel of the family of Enrico Tanzi, consul general of the Milanese and Lombards residing in the Kingdom of Naples, in the Bari cathedral of San Sabino; the Manfron Altarpiece, depicting the Madonna and Child Enthroned between Saints George and Christopher (the latter visibly similar to Titian’s Saint Christopher in the Venetian Doge’s Palace) and housed since 1827 in Lovere, constitutes a youthful masterpiece by the artist completed following the death of the condottiere Giulio Manfron, who was killed at the age of thirty-five in 1526 during the siege of Cremona. Commissions obtained by the painter in Venice that led him to travel to other parts of the peninsula as early as the 1520s, such as the commission he received in Noale to create one of his most monumental paintings, namely the St. George Slaying the Dragon for the church of San Giorgio in Noale at the behest of the jurist Alvise Campagnari. The saint in shining armor is depicted here while riding his horse he has already pierced the dragon, already on the ground to receive the last mortal blow, and next to it is the mutilated body of a young man. The princess observes the scene in the bush, while a group of onlookers climb over or look out from a late Gothic-style building to watch the fight. It is this imposing and monumental painting, restored for the occasion and now housed at the Pinacoteca Vaticana, that closes the exhibition, along with theAnnunciation of Caen set in an evocative architectural setting reminiscent of Serlio’s ancient structures and dating from around 1545 to 1550.

Paris

Paris

The itinerary does not follow a chronological thread, but proceeds as mentioned by themes and genres through the significant moments of the painter’s production, which also led him out of his territory. And given the necessity of bringing a selection of Paris Bordon’s works to the exhibition, to complement this, an extensive itinerary is proposed by the director of the Treviso Civic Museums Fabrizio Malachin to explore the artist’s masterpieces found in the Treviso and Veneto area, beginning with the permanent collections of the Museo di Santa Caterina, which preserve several of his paintings, including the monumental Paradise, continuing in the Duomo and the city streets and on to the Gallerie dell’Accademia in Venice, where it is possible to admire the Consegna dell’anello al doge, a masterpiece of which the Museo di Santa Caterina possesses a small-scale copy. Lacking in the exhibition are contextual works, but one can fill the gap first of all with a visit to the upper floor of the museum to become familiar with the environment in which Bordon lived and worked, and then by visiting the area, since the exhibition is inextricably linked to the geographical area that hosts it.

Almost forty years after the first Treviso monographic exhibition, Paris Bordon. The Divine Painter thus ranks in the history of initiatives, in terms of dissemination and accuracy, aimed at raising awareness of the art of the illustrious pupil of Titian, who knew how to make his way into becoming one of the greatest artists of the 16th century Veneto.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.