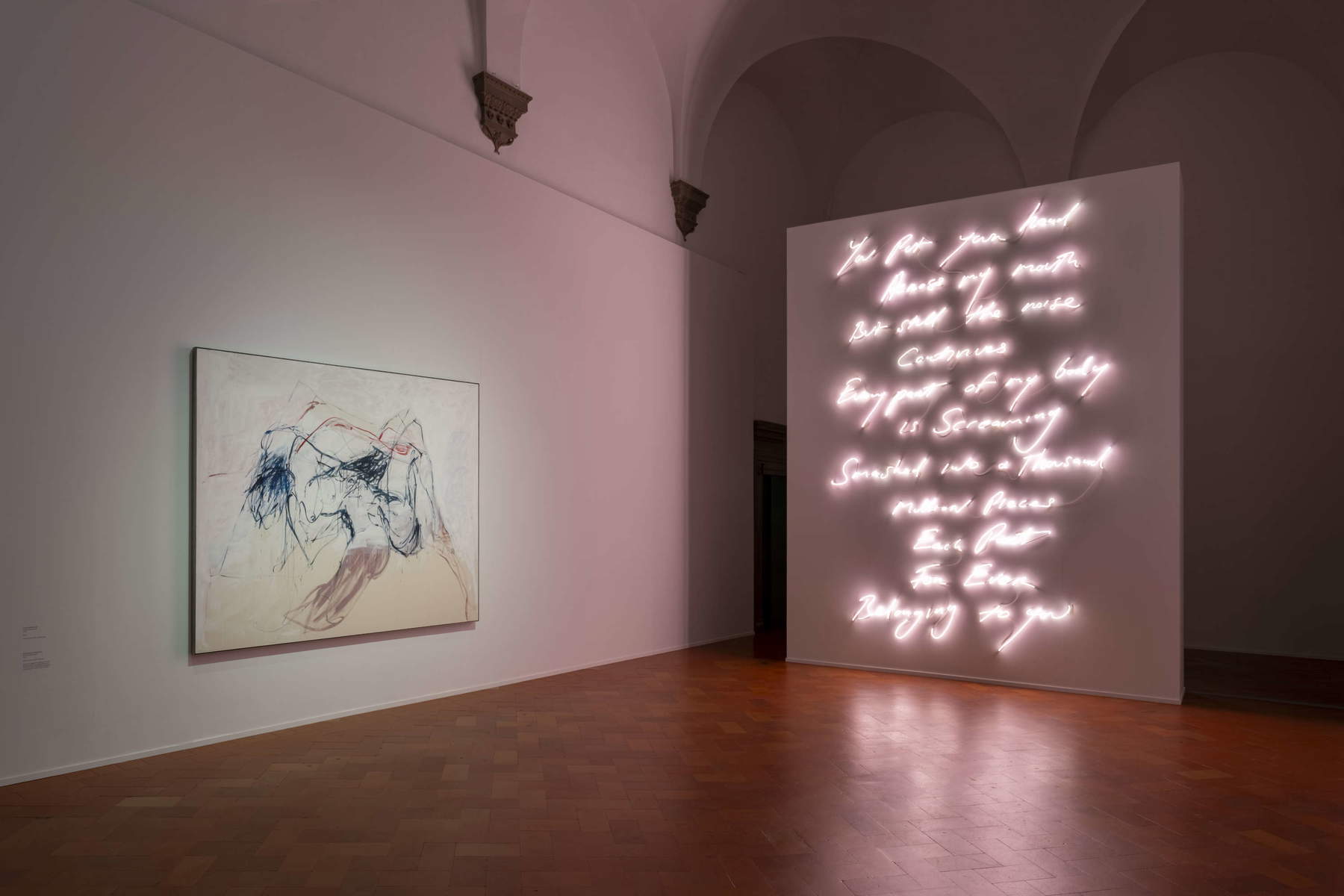

Tracey Emin. Sex and Solitude is the first major exhibition dedicated to the British artist in Italy. At Palazzo Strozzi in Florence it will be possible to visit until July 2025 an exhibition with more than sixty works, created over a period of time from the 1990s to the present day. Sculptures, paintings, embroideries, and neon reveal Emin’s complex universe, in which intimacy and vulnerability coexist with a visionary “violence” reminiscent of Expressionism, Munch above all (Emin’s great passion, as she herself has repeatedly declared), but at the same time the great authors of the twentieth century, such as Francis Bacon, Giacometti, and Louise Bourgeois. The nervous immediacy of the sign, the plasticity of the tampered body, the essentiality of the forms that reveal all their corruptibility, affirm a rigorous attention to themes that have always been fundamental keys to the art of the past as much as to that of the present. The red thread of the entire exhibition project is, in fact, precisely the body as the ultimate scenario of the skirmishes of existence. Body of desire, of sex, of exhaustion, of isolation, of corruption. To put it in a word that could sum up the entire exhibition, we are before passion, in the dual value of pleasure and sacrifice.

Poetry is the living flesh of language, and there can be no distance between lived life and creative labor. If the sign is wound, a revelation of an afterlife already operating in life, the word turns out, in stark and diametrical opposition, to be the treasure chest of secrets, often dramatic, other times iridescent and blinding that we keep deep inside. Tracey Emin knows this well and expresses it with a corollary of figures that, sketched out, impose themselves on our attention without filter, without sophistication. Emin questions the organism, abolishing spatial constraints, returns to the immediate, the acerbic, voyeuristic stroke. Her urgency and expressive intensity isolates the fragments of an improbable anatomy, putting the subject in awe.

Figure art, in the Deleuzian sense. Figure as a diagram of organic lines. And the philosopher went so far as to say that “painting must become an offense to the eyes.” It is as if there is a continuous search for a disturbed pathos. It is impossible to separate Emin’s biographical universe from her creative process, from the wounded, torn bodies congealed in a painful lump of vitality and at the same time fragility. To exist for her is to create and to create is to r-exist. To find an escape route, a traverse to the rigid straight line of the repetitive day-to-day. Then again, Brecht stated, “the toil of getting up every day, putting on one’s pants, washing, etc., and knowing that this will never end. That is the real tragedy.”

The chaos reconstructed in the room/installation Exorcism of the last painting I ever made, from 1996, catapults us into the other order of the studio of an artist who perceives all the occult load of painting practice. The suspended, rekindled pictorial gesture, the din of colors that denote the vital space in which there can be no distance between the everyday of clothes being laid out and the attempted eternity of the artistic operation. The absent body, or rather externalized by three photographic images that capture the performance that Emin herself held again in 1996 inside that studio room, reveals the breakdown of any balance between model and performer, between action and surrender, between fragility and vigor. In more recent paintings, such as in the large canvas Take me to heaven of 2024, this vigor has the character of the wound flaunted by a sanctified body. A female deposition complete with a halo certifies the sacred as a state of pain, prostration, redemption and ascent to heaven. These are works in which a doggedly perpetrated attempt to restore the suffering tangibility of the flesh through the swirling skirmish of brushstrokes is evident. They are inflicted marks, like razor blows, like deep cuts that a few fields of color attempt to stitch back together with difficulty.

Certainly Emin’s art is sincere, pure, in some ways absolute in its necessary intensity. Says the artist, “Exhibiting, in itself, has a cost. ”I am myself and I am extremely honest,“ ”and it’s not a game it’s what I do, what I create. My works do not come out as shit, vomit, semen. It is my art, in that is magical art, it is spiritual. I am a channel of it, it goes through me and then it comes out. Sometimes I have control, sometimes I don’t but if I wasn’t sincere, art would be meaningless to me, while it is of the utmost value to me. It is my work, it is my vocation." And in this vocation the theme of remembrance, of the past, is no less urgent than those mentioned so far. In the small paintings, as in the 2020 series entitled A Different Time, the somber, bluish, gray colors trace attempts to restore memory. Fragments of interiors, beds, sofas, sinks, evanescent spaces in which human presence seems to have vanished, seems to have merged with the dim light filtering far away. The intimate lyricism, accentuated to the size of these paintings, has no flavor of serenity; on the contrary, a feeling of farewell, of detachment prevails, as if they were hasty visual notes trying to nail down the feeling of a moment, the ecstasy of the fleeting moment, the decay of the inexorable passing of time.

I heard two dissonant (indeed: diametrically opposed) voices on the exhibition. The first praised the extraordinary freshness, immediacy of gestures, as well as the poetry underlying the entire body of work. The second mercilessly criticized a hasty instinctivism that today would come across as academic and a pretentiousness that relies more on the underlying narrative than on the quality of the more or less repetitive and unresolved individual works. Usually an event that generates such distant points of view is an excellent opportunity to confront the phenomenon of contemporary art that is not always accessible and not always immediate and convenient to decipher. I would say that in this Emin has always managed to bring out uncomfortable questions and reflections that revitalize confrontation in the agon of contemporary art production.

The author of this article: Fabrizio Ajello

Fabrizio Ajello (Palermo, 1973) è un artista e ricercatore che riflette e interviene attraverso vari media sulle dinamiche dei modelli culturali, indagando in particolare i temi del sacro, della Vanitas, della memoria individuale/collettiva e del rapporto tra spazio materiale e virtuale. Negli anni ha reinventato l'uso di medium tradizionali come il disegno, la fotografia, la scultura, per produrre opere di intervento e installazione site specific. Attualmente, la sua attenzione è focalizzata sul rapporto tra processi onirici e modelli di interazione e rimediazione attraverso applicazioni TTI (Text to Image software).Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.