The birth certificate of Renaissance painting is not to be sought, as one might imagine, within the walls of Florence, under Giotto’s bell tower, in the shadow of Brunelleschi’s dome. As far as we know, Florence was not the first recipient of a panel capable of speaking the new language. It is necessary to go further south, among the Valdarno countryside dotted with woods and olive trees: the Renaissance in painting was born in the parish of San Giovenale, a tiny rural village just below the hills separating the Upper Valdarno from the Casentino. In the village church stood an altar whose patronage belonged to the Castellani family, a dynasty of merchants and bankers who were among the most prominent in Florence, even though they came from Cascia di Reggello, the hamlet just beyond San Giovenale: it was probably a member of the family, Vanni Castellani, who commissioned Masaccio to paint the altarpiece for the high altar, destined to become the first cornerstone of the new painting. The Triptych of St. Juvenal was delivered by that scruffy, revolutionary genius on April 23, 1422, according to the date written on the lower border in humanistic capitals instead of Gothic letters. To be sure, the painting was made in Florence and then sent to the Valdarno, and we are not even certain that it reached San Giovenale immediately: there are those who think that it remained for a few years in Florence, where the artists working in the city could see it and assimilate the powerful, overwhelming force of novelty that that painter in his early twenties had unleashed on his three panels. But the suggestion remains to think of a painter at the beginning of his career who sanctioned one of the most profound ruptures in the history of painting by painting for a small country church. And exactly six hundred years later, on April 23, 2022, the first exhibition built around this fundamental triptych opened in Cascia di Reggello: Masaccio and the Renaissance masters in comparison is the very high tribute that the Masaccio Museum of Sacred Art is dedicating to his main work, as part of the Florentine museum’s Uffizi Diffusi and the Fondazione CR Firenze’s Piccoli Grandi Musei projects.

The Triptych of St. Juvenal therefore had to wait until its birthday to have an in-depth study dedicated to it. And as is well known, round anniversaries can lead to outcomes of the opposite sign, since they can bring exhibitions set up more for duty of date than to open up real opportunities for study and understanding, or on the contrary they can offer the opportunity to build up exceedingly relevant focuses. The Reggello exhibition certainly belongs to the second case in point: between the rooms of the Masaccio Museum, curators Angelo Tartuferi, Lucia Bencistà and Nicoletta Matteuzzi have created an extremely dense exhibition on the origins of Renaissance painting, reconstructing contexts, proposing unpublished comparisons, advancing hypotheses, all in the meager space of only twelve works. The Reggello exhibition, however, is proof that if the scientific project is solid and well planted on its foundations, there is no need for long carrels of loans to leave a trace on the public. A project that has been made possible by widening the traditional mesh of the Uffizi Diffusi, since in Cascia di Reggello not only works from the great Florentine museum are arriving: to compose this exhibition, important pieces from private collections as well as from churches and museums in the area have been gathered together. The result is an exhibition that has managed to combine, on the one hand, the spirit of the Uffizi Diffusi, that is, to bring works back to their territories of origin by offering small museums in the Tuscan province the possibility of reknitting the threads of contexts that have been unraveling over the centuries, and on the other, the setting of a traditional exhibition.

It may seem strange that a work so central not only to the vicissitudes of its time, but also to those of twentieth-century criticism, which has been the focus of long and impassioned discussion around the Triptych of San Giovenale, has never been the main protagonist of an exhibition event dedicated to it. The astonishment can, however, be mitigated by the long exhibition fortune of the work, well reconstructed in the catalog by Nicoletta Matteuzzi: after having survived unscathed the looting of the Nazis during World War II (also in the catalog, Maria Italia Lanzarini publishes the testimony of Aurelio Bettini, Renato’s nephew who was sacristan of the church in 1944: according to Aurelio’s account, his father allegedly hid the Triptych of St. Juvenal first behind the headboard of his bedroom, which was, however, requisitioned by a German officer who therefore unknowingly slept under Masaccio’s masterpiece, and then, deeming the hiding place no longer safe, moved it to a cellar, taking advantage of a moment of the Nazi’s absence), the Triptych of St. Juvenal was rediscovered in 1961 by Luciano Berti, the first to formulate Masaccio’s name for the work. The proposal is said to have met with some resistance (above all that of Roberto Longhi, Ugo Procacci, Carlo Volpe and Luciano Bellosi), on the grounds that the quality of the work does not reach the same degree of excellence as other products certain to be by Masaccio’s hand: arguments that Tartuferi rejects, rightly pointing out that “some uncertainty is perfectly understandable even in a rookie genius, and at the same time it seems unlikely that the scurvy 20-year-old from Valdarno was already endowed with an overcrowded array of helpers.” In the year of Luciano Berti’s recognition, the work was immediately taken to Florence for a lengthy restoration that would keep it away from Reggello and even from the eyes of the public until 1988, except for a few sporadic exhibition moments, such as the 1972 exhibition Firenze restaurata, and the comparison with Beato Angelico’sAnnunciation of San Giovanni Valdarno staged in 1984 in Fiesole. Then, when the restoration was finished, the work returned to Valdarno, but it was decided, for its safety, to exhibit it in the parish church of San Pietro in Cascia, where it remained until 2007, when it was brought to the Masaccio Museum, which had opened its doors in 2002. Since 1988 there have been further technical and scientific investigations, another restoration (that of 2011), and participation in five other exhibitions. Finally, since 2014, the work has not left its museum and has, if anything, undergone a long and continuous work of valorization that has employed the most varied languages (even a theatrical performance) and that this year culminates with the dedicated exhibition.

An exhibition that begins by transporting the public to early fifteenth-century Florence, a time when peace and economic stability ensured prosperity for a city where public works were bustling and where private patrons also competed to secure the services of the best artists on the market: it is a Florence where the elegant late Gothic culture of a Lorenzo Monaco or a Gherardo Starnina is rooted but where naturalist impulses are already manifesting themselves, which at the beginning of the century translate into a neo-Giottism capable of smoothing out the sharper points of late Gothic abstruseness and extravagance. The first room of the exhibition thus presents the visitor with the different languages that characterize Florentine figurative culture at the beginning of the 15th century: one thus puts oneself in the shoes of a young Masaccio who, at a very young age, left his native San Giovanni Valdarno to move to Florence at the age of seventeen, in 1418, going to live in the neighborhood of San Niccolò Oltrarno to complete his training in a local workshop, perhaps that of Bicci di Lorenzo, a painter with whom, as the Reggello exhibition intends to demonstrate, Masaccio reveals some points in common at the start of his career.

In the room, therefore, one can admire what Masaccio could see at the time of his move to Florence: we begin with the earliest work in the exhibition, Lorenzo Monaco’s triptych with Our Lady of Humility and Saints Donnino, John the Baptist, Peter and Anthony Abbot, on loan from the Museo della Collegiata in Empoli, a manifesto of the late Gothic finesse that became established in the city in the latter part of the 14th cent, and to which refer the elongated proportions of the saints (but also those of Saint Donnino’s dog), the sinuous and unnatural lines of the draperies, certain preciousnesses such as those of the cushion on which the Virgin sits, and the almost metallic iridescence of the saints’ robes. A work of 1404, the Empoli triptych is considered the first fully Gothic work by a painter who had been trained in the wake of Giotto’s idiom: the beginning of work on the North Door of the Baptistery of Florence, the undertaking that Lorenzo Ghiberti had begun just the year before, may well have contributed to orienting him toward the new international Gothic style, but perhaps more decisive was the return from Spain in 1402 of Gherardo Starnina, about fifteen years older than Lorenzo Monaco, a point of reference not only for Lorenzo but for all the younger artists, and the first innovator of Florentine culture at the end of the 14th century. Demonstrating the wealth of experience Gherardo brought back with him from the Iberian peninsula is a highly refined Madonna and Child between Saints Anthony Abbot, Francis of Assisi, Mary Magdalene and Lucy, on loan from the Oriana and Aldo Ricciarelli collection in Pistoia: it is a work characterized by elegant, twisting lines, tender and delicate colors, sliced and tapering figures, and decorative motifs that themselves demonstrate a Spanishate taste (the carpet on which the two saints sit at the feet of the Virgin, for example). Finally, giving an account of the opposite pole is a Madonna and Child by Giovanni Toscani of about 1420, from the parish church of Santa Maria Assunta in Montemignaio: a work that stands out for its tender rendering of the affections, it is an interesting example of neo-Giottesque painting, capable of bringing back the language of the early fourteenth century without reproposing it slavishly, but updating it with some of the finesse typical of late Gothic taste, beginning with the course of the borders of the Virgin’s wide sleeves.

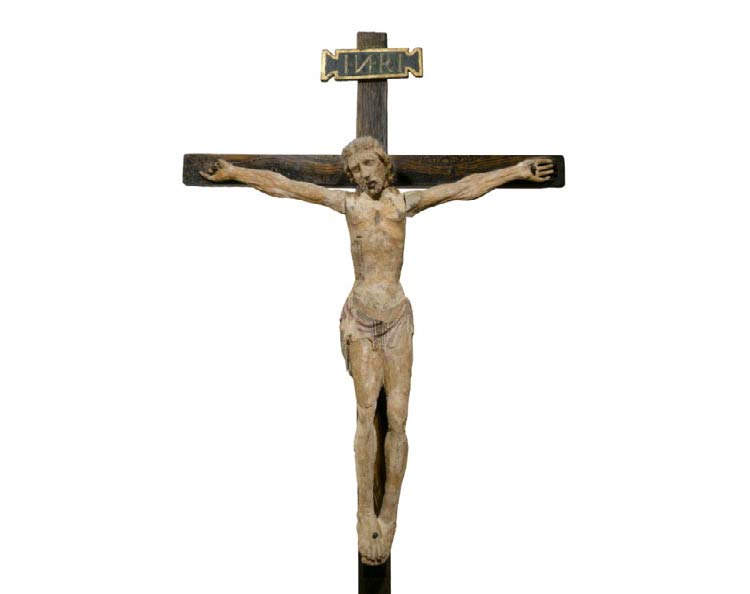

These, however, are not the masters with whom the young Masaccio was confronted on his arrival in Florence (Starnina himself died when the Valdarno artist was only twelve years old): they were other artists with whom he probably came into contact, and the second part of the room has side by side a couple of works fully participating in the artistic temperament dominated by the flamboyant painters of the International Gothic and the devotees of tradition, and who perhaps provided Masaccio with the first test beds on which to measure himself. From the church of San Niccolò Oltrarno comes an important loan, the left-hand compartment of Bicci di Lorenzo’s triptych, which Masaccio (again, however, admitting an early date and assuming that the Florentine painter began working on it in 1421) in all likelihood knew very well and perhaps kept in mind when he began work on the Triptych of Saint Juvenal (one will note the strong resemblance of Bicci’s Saint Bartholomew to the counterpart saint that Masaccio painted for his triptych in 1422). Similarly, Masaccio will surely have admired the Crucifix in the church of San Niccolò Oltrarno, another work that can be dated to the early 1420s: restored in 2021 (it is being exhibited in Reggello for the first time after the intervention), it now presents itself to our view with all the suffering it has endured over the centuries, which does not, however, prevent us from framing this work in a context of great renewal, since the anonymous author of this wooden sculpture gives us back a Christ whose face is pervaded by an expressive motion of pain and which, even in its still fourteenth-century setting, shows that it was already sensitive to the innovations that a decade earlier were being introduced by the crucifixes of Donatello and Brunelleschi, inescapable models for anyone who set about sculpting Christs on the cross from then on. The Crucifix of San Niccolò Oltrarno is therefore a work that, writes Grazia Badino, “already belongs to Masaccio’s world.” By contrast, the last work in the room, Giovanni dal Ponte’s Madonna and Child with Saints Nicholas and Julian, a painting that looks to the Iberianisms of Gherardo Starnina (especially in the way the faces are illuminated and brightened), but which is also imbued with, writes the young scholar Alice Chiostrini, of “elements that foreshadow an interest in the protagonists of late Gothic humanism, such as Gentile da Fabriano, and of the Renaissance, such as Masaccio” (the plastic relief of chiaroscuro contrasts, for example, which will improve precisely through contact with Masaccio).

The Triptych of Saint Juvenal is at the center of the second room, in an unprecedented comparison with Beato Angelico’s Triptych of Saint Peter Martyr. We dwell first, however, on Masaccio’s masterpiece, and if it is true, as Giuliano Briganti asserted, that Masaccio’s first master was Brunelleschi, then this alumnus at a distance is evident from the Valdarno artist’s first known work: the young artist on his debut immediately makes central perspective his own, applied in a solid, firm and rigorous manner as can be seen by looking at the foreshortening of the ivory throne of the Virgin and the lines of the floor (which is shared by all three compartments: Masaccio imagines a unitary space) that converge toward the ideal, but also geometric, center of the composition, namely the face of the Mother of God, where the artist places the focal point of the composition, thus assuming a bottom-up view (the real reason why the Madonna appears to us a little elongated). The figures are firm and their volumes full, truly inserted in space: the plasticism learned from observing the works of Brunelleschi and Donatello enjoys an accomplished rendering of perspective. The discoverer of the Triptych of San Giovenale, Luciano Berti, spoke of a “continuous insistence on three-dimensionality,” mastered with great mastery by Masaccio, evident also from certain details such as the feet of the Child “which flow [...] into the frontal view without falling, as hitherto, on point,” or the hands of the Virgin “caught in a double situation of profile, horizontal and vertical,” and again the angels from behind with their arms stretched forward. And one could then mention at least the book of Saint Juvenal, in whose writings Masaccio’s handwriting has been recognized through a comparison with an autograph document. The saints (i.e., from the left, Bartholomew, Blaise, Juvenal and Anthony Abbot), already alien to the flexuosity of the International Gothic, are investigated in their frowning expressions with great psychological acuity, and their figures, as Berti already noted, hark back to Donatello: look at the Saint Juvenal, who brings to mind the princess of the predella of the San Giorgio, or the Saint Blaise who recalls the bronze Saint Ludovico executed for Orsanmichele and now in the Museo di Santa Croce. Masaccio, Lucia Bencistà points out, knew, moreover, how to “grasp from the very first Florentine steps, through individual elaboration and rethinking, the perspective and plastic novelties of the new art of Brunelleschi and Donatello, but also, and above all, the moral and cultural value that flowed powerfully from such novelties.”

In front of him, the exhibition curators placed, as mentioned, the Triptych of St. Peter Martyr by Beato Angelico, the first painter to fully grasp the scope of the Masaccio revolution. The friar painter’s machine shares some innovative solutions with the Triptych of St. Juvenal, although we do not know whether Angelico arrives at his conclusions independently or after measuring himself against Masaccio’s works. This is a question that has long been debated by art historians. There is no doubt, however, that certain cues are common to the two artists: above all, the idea of linking the three compartments so that the figures share a unified space, while preserving the traditional tripartition, and the same spatiality that appears in the two scenes of the Preaching and Martyrdom of St. Peter Martyr painted above the cusps, which are so original that in the 1950s they were considered late additions by Benozzo Gozzoli. It is actually the product of the hand of a Beato Angelico who, Angelo Tartuferi writes, “is already capable of exhibiting a control of spatiality (in the perspective placement of the pulpit and the buildings in the background) and an absolute mastery in the restitution of the plastic masses (the female figures crouched on the ground wrapped in large cloaks), which accredit him precisely as an independent sodal of Masaccio at the beginning of the 1520s.” The Triptych of St. Peter Martyr marks a turning point in the career of Guido di Pietro, who from being a “man of the fourteenth century” (so Tartuferi in his essay in the catalog, all dedicated to the comparison between Masaccio and Beato Angelico) trained in the more traditional Gothic language, is transformed into one of the main innovators of his time: or rather, he turns into an artist who, according to recent hypotheses, should be placed alongside Masaccio in the renewal of painting, although the two were divided by a different conception of their naturalism (modern and decidedly more worldly that of Masaccio, universal and mystical that of Angelico: two visions of reality that, however, “from the point of view of stylistic outcomes turn out instead to be practically identical,” Tartuferi points out).

Accompanying the comparison between Masaccio and Beato Angelico are works by two other greats of the time, Masolino da Panicale and Filippo Lippi. The former is present with the Madonna of Humility from the Uffizi, a work from the mid-1910s, still obviously unaware of what was to come: An elegant, gentle and rare product of Masolino’s early activity, the Madonna of Humility represents one of the pinnacles of late Gothic Florentine art, a work, writes Nicoletta Matteuzzi, “marked by a calm and sinuous grace, due to the elongated forms of the figures, the broad falcatures of the draperies, the extreme delicacy of the chiaroscuro and the luminosity of the color range.” Masolino, too, would shortly thereafter be fascinated by Masaccio’s innovations, and as is well known he would also have the opportunity to measure himself directly against him in the Saint Anna Metterza and especially in the undertaking of the Brancacci Chapel. The Madonna and Child by Filippo Lippi, the most Masaccio-esque of the painters of early 15th-century Florence, whose presence in the exhibition is determined precisely to illustrate the earliest ways in which Masaccio’s language spread: an early work, it shows clear references to Masaccio not only in the full and solid volumes of the figures, but even in the niche on which the Madonna stands, a reference to the Trinity painted by Masaccio in Santa Maria Novella in Florence.

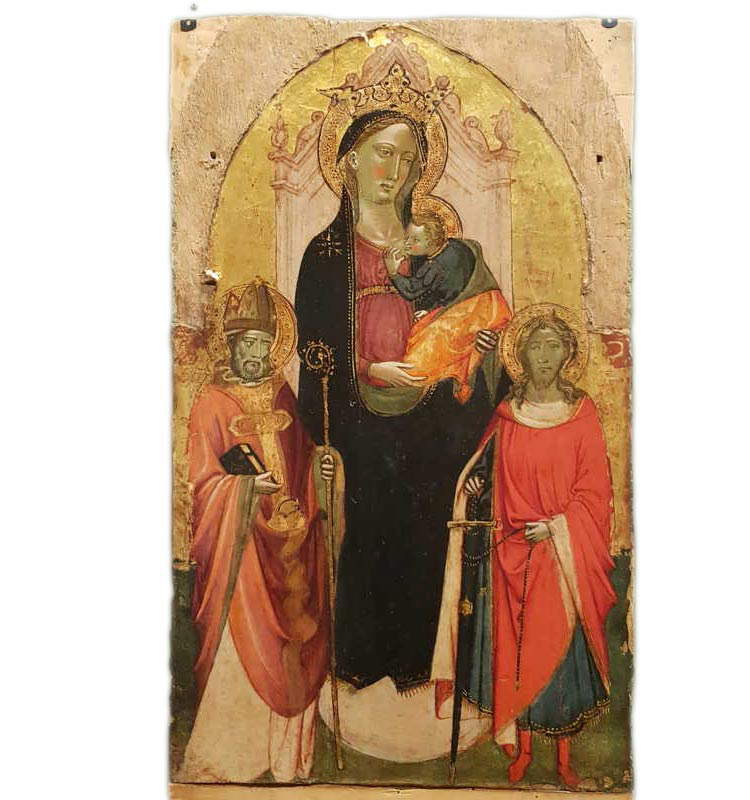

The exhibition closes in the next room, where there are two panels, a Madonna and Child with Saints John the Baptist and James the Greater by Francesco d’Antonio di Bartolomeo and a Madonna and Child Enthroned and Two Angels by Andrea di Giusto, tending to show how the Florentine painters’ attention to Masaccio had not waned even after the precocious death of the Valdarno artist, who died at only twenty-seven. Francesco d’Antonio di Bartolomeo is according to Tartuferi one of the most original interpreters of Masaccio (but also of Beato Angelico and Masolino): the Virgin and the Herculean figure of the Child could denounce a direct dependence on the Triptych of San Giovenale, despite the presence of the two much slimmer saints, which demonstrate instead the breadth of the cultural horizons of this curious and singular painter. Less original and more schematic is the interpretation of Andrea di Giusto, moreover Masaccio’s collaborator in the Pisa polyptych in 1426: the mixture of new elements (the measured plasticism of the Virgin, mindful above all of Beato Angelico’s Madonnas, the foreshortened perspective) and traditional ones (the course of the gilded border of the Virgin’s mantle, the fineness of the gilding) give us back the traits of an artist who, writes Daniela Matteini, “seems to have achieved a balance between the adherence to the traditional Gothic conception and the attention to the formal modules of the masters of the early Florentine Renaissance.”

There is, finally, an appendix to the exhibition inside the parish church of Cascia. A fixed appendix, one might say, since the fragment of fresco with theAnnunciation by Mariotto di Cristofano, a neo-Giottesque work executed around 1420, was considered an integral part of the itinerary of the exhibition, given its role as a living witness to the events that affected Valdarno in the first decades of the 15th century. What’s more, Matteuzzi recalls how certain the contacts between Mariotto and Masaccio are (the former had married the daughter of Masaccio’s stepfather in 1421), plus the two painters were both from San Giovanni Valdarno and separated by only eight years of age, although the older Mariotto does not appear in any way close to Masaccio’s innovations, “preferring rather,” Matteuzzi writes, “to remain faithful to the fourteenth-century tradition or to update himself on texts by other painters, such as Lorenzo Monaco and Beato Angelico.” The Cascia fresco, however, is another figurative text that Masaccio may have seen during the period when he was waiting for the Triptych of San Giovenale. It is therefore difficult to think of an exhibition more connected to the territory than the one that was set up for the 600th anniversary of Masaccio’s first masterpiece.

Masaccio and the masters of the Renaissance in comparison is a choral exhibition, to whose excellent result a heterogeneous group of scholars of various backgrounds, including experts and young people, has contributed. They have been able to develop a harmonious and balanced itinerary, and to recount it in a catalog of considerable scientific and cultural depth, literally translated into popular terms in the impeccable apparatus of the rooms. The apparatuses, moreover, also stand out in terms of sustainability: there are no invasive panels that, in the cramped spaces of the Masaccio Museum, would have produced nothing but visual pollution, and they have, however, been replaced by nimble QR Codes that refer to texts published on the web and a pleasant free audio guide that accompanies the public almost work by work. This is a solution that even the major exhibitions of the most famous museums should seriously consider to lighten their tour routes. Masaccio and the Renaissance masters in comparison is then an exhibition with a two-faced nature: it tells a story that was born in the deepest province, but from which the foundations of Renaissance painting sprouted, and it is set up in the rooms of a small museum hidden in the Valdarno hills, but it speaks with the tools of the most up-to-date museography. The imprint of the Uffizi, after all, is marked and clearly distinguishable, and the Reggello exhibition can be counted among the most remarkable outcomes of the Uffizi Diffusi project, which marks another step in raising its already high standards of quality. Masaccio and the Renaissance masters in comparison is therefore an exhibition that, in short, points the way to a future that will be increasingly under the banner of occasions such as the one in Reggello: exhibitions of limited size, founded on high-level scientific projects, aimed at the valorization of the works and the history of the territory, capable of speaking to scholars as well as to the general public with identical ease.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.