There is an exhibition in New York that is bringing Italian art of the 1950s and 1960s to the U.S.

Among the various routes that connected Europe and the United States in the postwar period, there was one that was particularly dear to the art world: Rome-New York. In the 1950s, as artists, writers and intellectuals returned from exile and prison camps, Rome emerged as the center of a new avant-garde. All Italian, untethered from the Parisian influence that had largely defined the first half of the twentieth century. New York, on the other hand, shone with the light of change, illuminating the rest of the world with the promise of a new horizon. In a ménage that united art and society, the link between the two cities took on the flavor of a handover, or at least an irreversible contamination. Rome, with the decadent but still fascinating legacy of a long classical, humanistic and baroque tradition. New York, ocean of freedom with no prior debts, cradle of novelty even in the artistic field, proponent of a future yet to be written. So it happened that, thanks to connecting figures like the gallery owner from Trieste, but based in New York, Leo Castelli, artists placed at the extremes of the Atlantic met, this way or that, for work, love, friendship. In short, for art.

But what did they have to offer each other? America, launched by consumerism on the path of Pop Art, found in Italy a more intimate form of expression, linked in particular to gesture and matter, an Informal imbued with ancient lyricism. Italy, also propelled by the economic boom, is captivated by the immediacy of American consumerist iconography, so much so that it incorporates it into the dominant aesthetic at the time: the new realism. The New World thus yearned for the culture of the Old; the Old World longed for the transformations of the New. This crucial relationship is addressed these days at David Zwirner’s New York office in Chelsea in the exhibition Rome/New York, 1953-1964, curated by David Leiber and on view through Feb. 25.

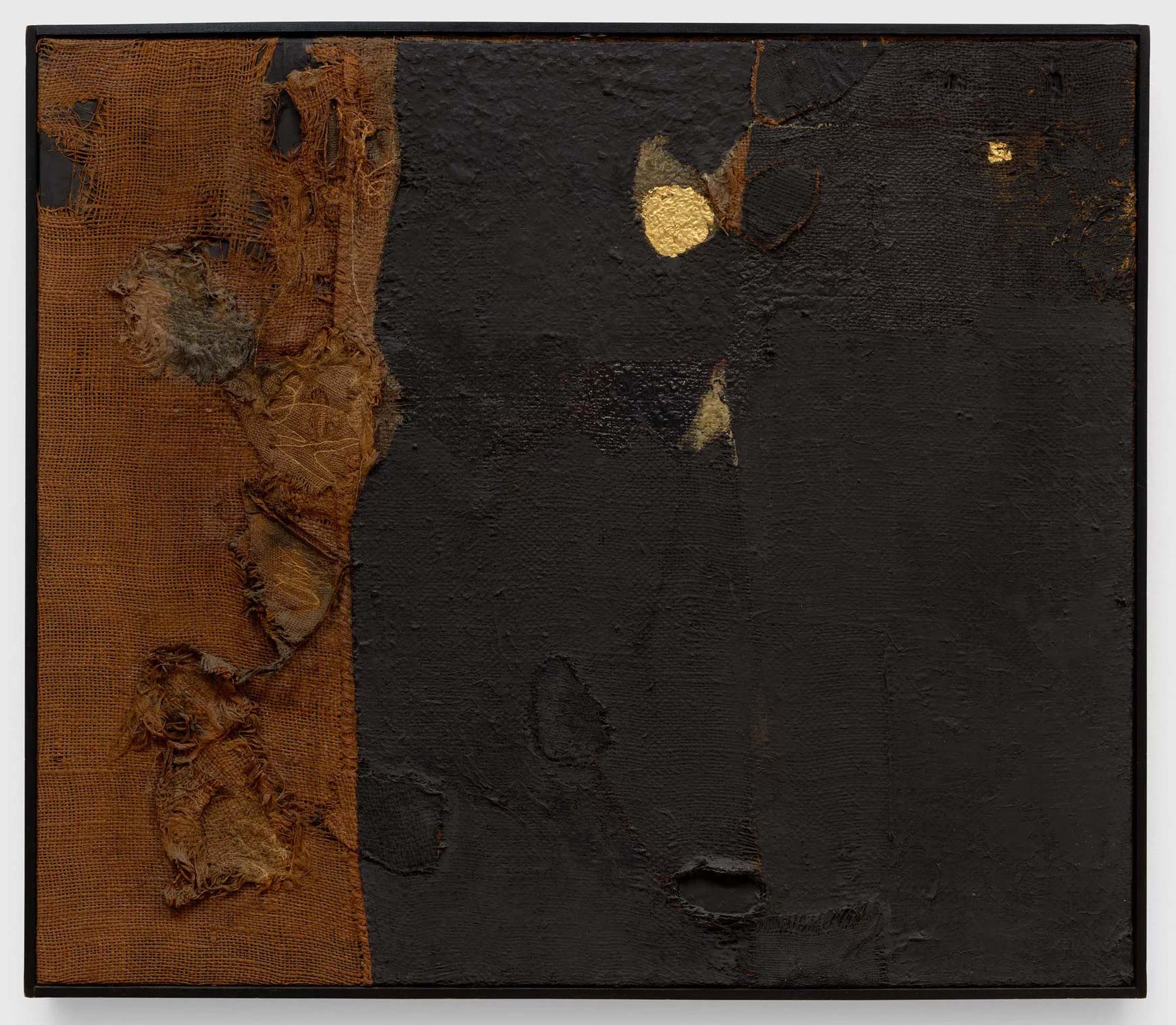

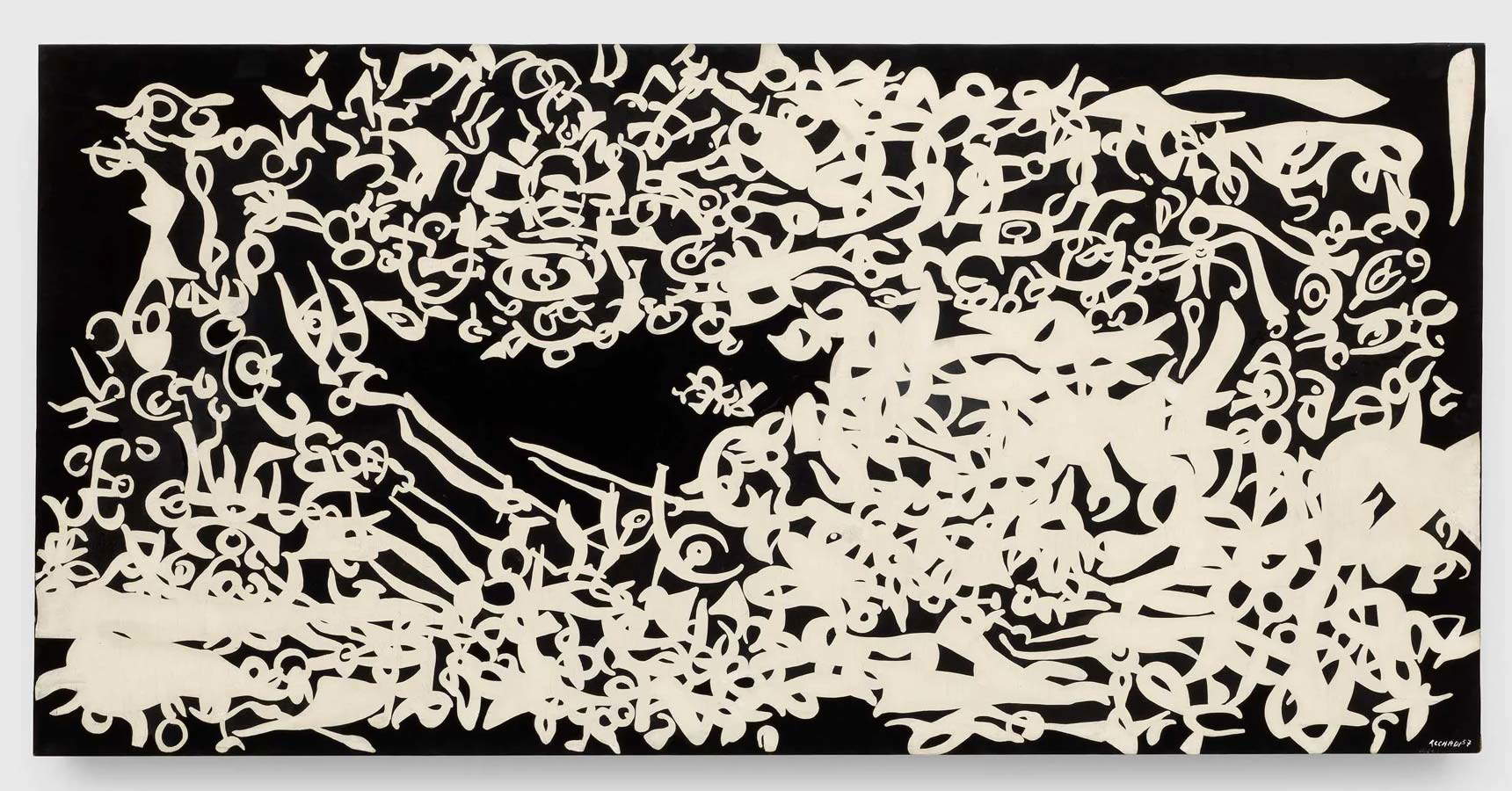

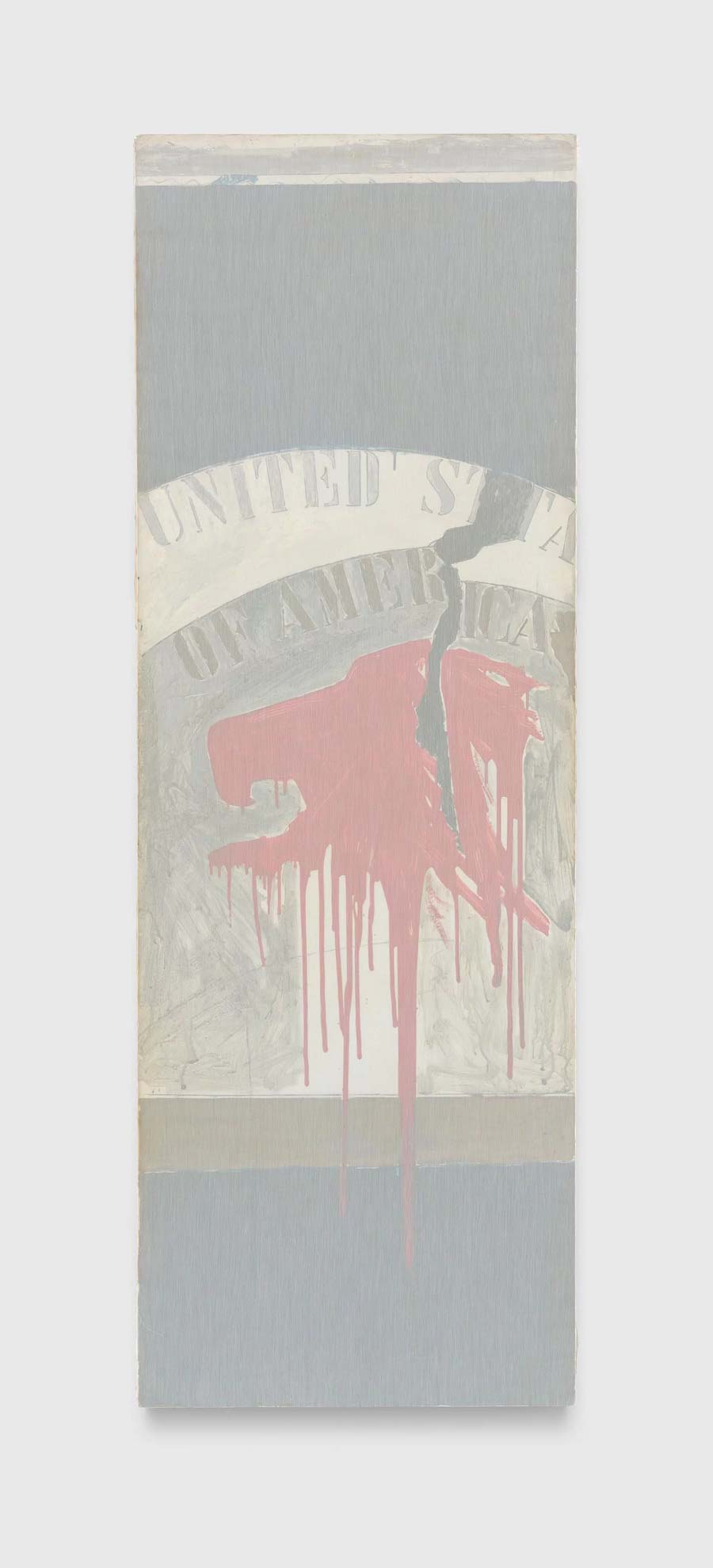

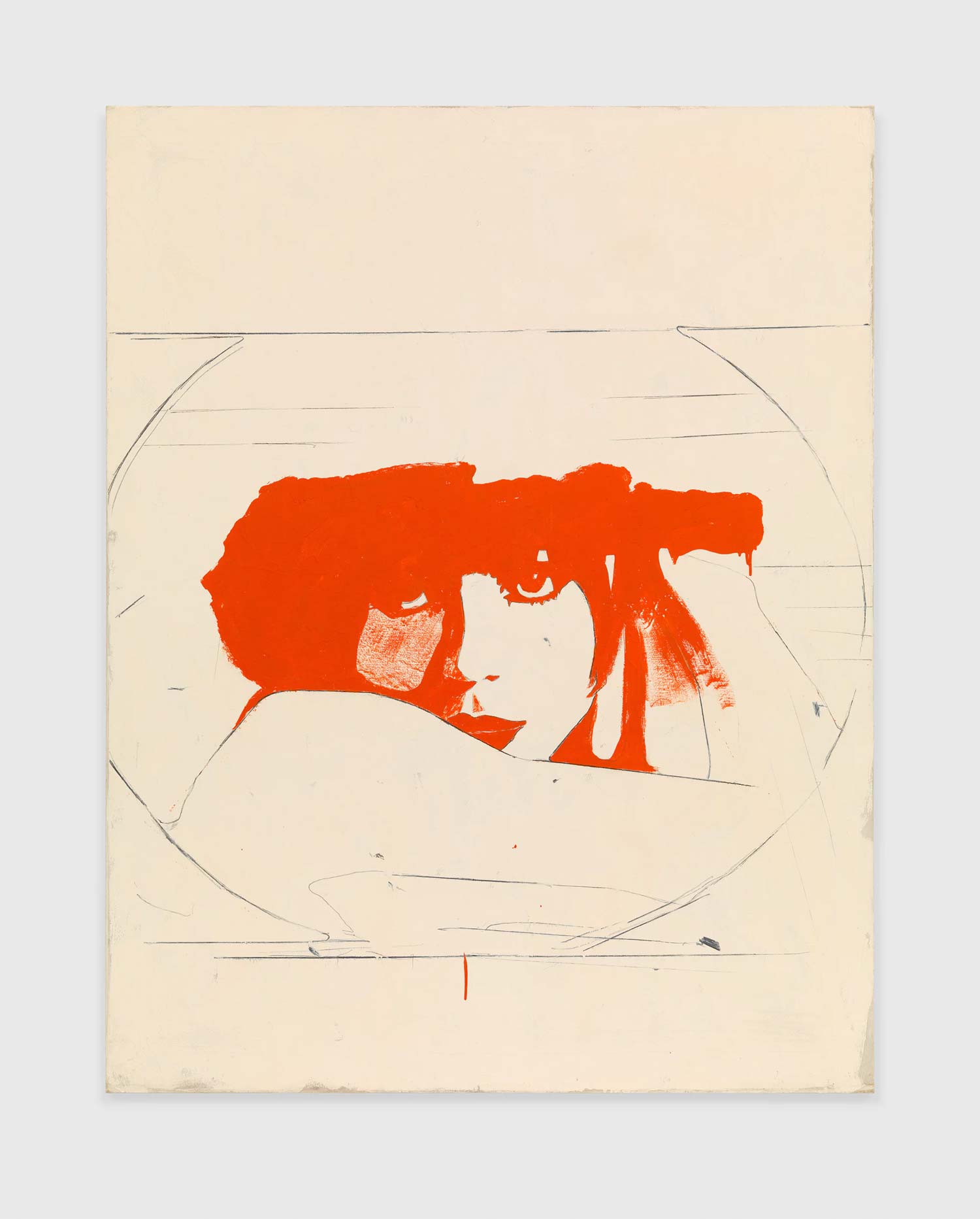

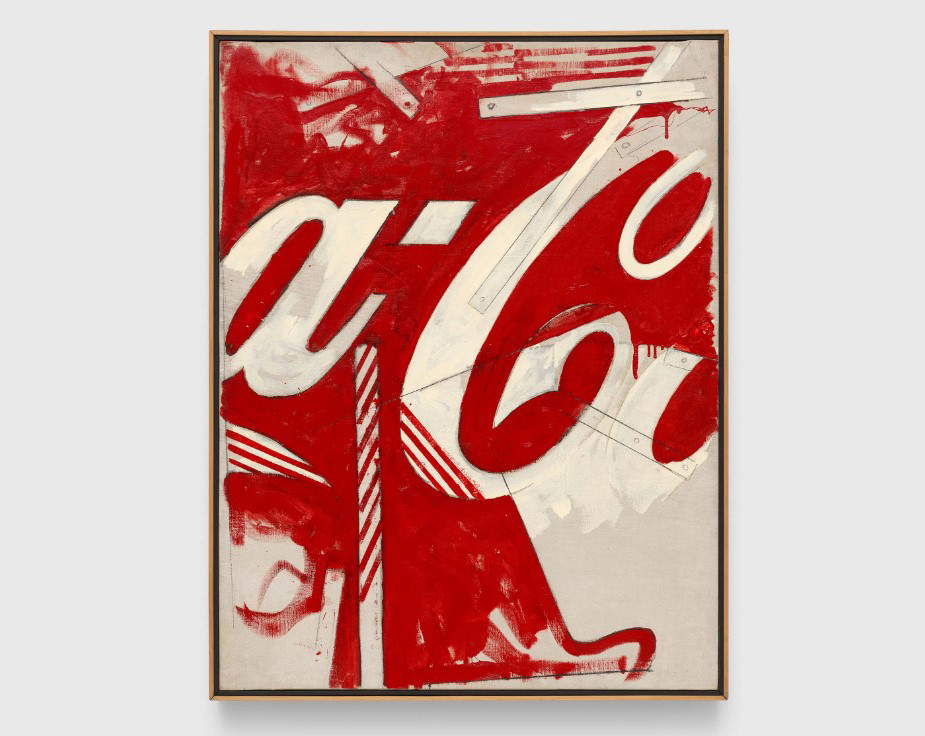

A visual narrative of intertwined worlds and aesthetics, as is evident by comparing the artistic outcomes that the respective authors proposed. In the works of artists who grew up with a neo-realist imprint - such as Franco Angeli, Tano Festa, Giosetta Fioroni, Mimmo Rotella and Mario Schifano - one notices from the mid-1950s onward the annexation of elements drawn from the sphere of consumption or from the urban dimension of an American matrix. In particular, Schifano, who in 1962 exhibited at Sidney Janis in New York in the historic exhibition The New Realists, became the spokesperson for a pictorial practice that incorporated fragments of images, advertisements and texts. It is the birth of Italian Pop Art, which is seduced by the glittering allure of overseas consumerism but is able to transport it to a less immediate, more layered, richer in implications, more classical, more European dimension. Reverse contamination, on the other hand, in the case of the Informal, an abstract current characterized by research into matter. It was figures like Afro Basaldella, Toti Scialoja, Alberto Burri and Piero Dorazio who brought to New York-with exhibitions in the galleries of Eleanor Ward, Catherine Viviano and Leo Castelli-the sublime peaks of a movement that would go on to lose its bite in the mid-1960s.

At the same time, several New York-based artists such as Philip Guston, Franz Kline, Willem de Kooning, Robert Rauschenberg, Salvatore Scarpitta and Cy Twombly were exhibiting in Rome, notably at Irene Brin and Gaspero del Corso’s Galleria dell’Obelisco and Plinio De Martiis’ Galleria La Tartaruga. A dense web of solo and group shows that determined the creative routes of the artists in question. And which Zwirner takes up again, with a curatorial (and commercial) operation aimed at powerfully rekindling the spotlight on the best post-war Italian pictorial achievements in America (thus on the global market), juxtaposing them in such a way as to redound to cross-references and connections. In fact, Rome/New York, 1953-1964 focuses particularly on Italian artists, many of whom-including Angeli, Perilli, Novelli-are recognized and acclaimed in Italy but remain less well known in the United States. But also virtually unknown authors such as Luigi Boille, who nonetheless made himself the protagonist of important exhibitions in the period under consideration, including one at the Guggenheim in New York alongside Fontana, Castellani and Capogrossi. Or Conrad Marca-Relli and his complex collage-based painting practice. Born to Italian immigrant parents, Marca-Relli was a key point of contact between the two art communities, connecting dealers and artists and helping to establish the relationships that made this period so important, unique and perhaps unrepeatable. In fact, as early as 1964, the year Rauschenberg won the Golden Lion at the Venice Biennale, communications began to become more sparse. Rome lost its centrality in the Italian artistic avant-garde, with Milan and Turin attracting more and more artists and investment. New York, on the other hand, remained there, the nerve center of the world art system, and there it still is today, at the apex of the international art system. And he does not forget those years when, if he looked out towards the ocean, he saw Rome.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.