For us, the 1960s were the classical and academic moment of the twentieth century that after the wartime débâcle repositioned Italy within the horizon of the modern by making it part of a mentality based on a “total” communicative strategy, a practice that a few centuries earlier had responded on the Catholic side to Protestant rigorism and pessimism: Counter-Reformation and communication were the informing principle and rhetorical tool to overcome the “moralism” of the evangelical movement. Similarly, in the “counter-reformation of the modern” we can see today the objective correlative of a new challenge to post-war social and cultural depression through a dream of productive and emotional wealth sprung from the optimism of well-being. Object aesthetics and gratifying consumption. It was not enough just to believe in it; the message had to be accompanied by a concrete promise that interacted, in reality, with a visual communication embodied by the object. Art was the medium of this social “counter-reformation” that would land from Pop to postmodern playfulness. Appearance was an almost total cult, so to speak, because it led the consumer to hope for what advertising promised him. Almost a sacrament of well-being.

The profound realization that the “medium is the message” is not the result of philosophical speculation but of a knowledge that matures in the mere “realism” dictated by a handbook of concepts and works where, to stay with our comparison, Marshall McLuhan becomes the Paleotti of Late Modernity. What the avant-gardes had sown - think of the work of malleverie that futurism exerted on the forms of communication from which advertising as we know it today was born - became consumer conformism founded on the strategies of mass communication in the “global village.” And it was McLuhan who devised the “pedagogical” handbook, the cultural method - as did Paleotti’s Discourse on Sacred and Profane Images for the “re-education” of artists and churchmen - necessary to enact the logics of a future society of Welfare, while the earth accelerated its rhythms of movement and interrelation and recomposed everything and everyone within a space of communicative awe, transforming the far into the near and making our lives dependent on the flow of information beyond that friction still present in the “Gutenberg galaxy.”

The 1960s are thus those of the image in power. But it is not the imagination of the slogan that went “viral” in 1968, because image, it is now blatant, goes to power as the principal tool for the control of freedom; it is not, first and foremost, a means of liberation. The image binds the individual to the real by attracting and conditioning the imagination. The economic boom testifies that the 1960s is the decade where reality is normalized and bends to the optimism of prosperity. Now this vicious circle is unsolvable: everything is economic, and it is complicated by the entry of falsifying factors on the media scene. The new language today is codified in the “post-truth,” which is not a “non-truth,” but a different perspective of true and false, as indifference to truth; as Ionesco recites in TheImprovisation of the Alma: “The false true is the true false, that is, the true true true is the false false.”

On the planetary stage everything is normalized, everything is academic, i.e., harbinger of semantic and formal norms that regulate the strategies of “informed” consumption (until “buying advice,” sublime hypocrisy of the middle class suggesting what is to be appreciated, enters the scene), to produce-in the expectations of the propagating centers-economic effectiveness or simple conditioning.

What to do. Return the image to its initial “iconic” value (of a propaganda that is realized in the critique of its own object). Iconocracy is both a current condition and a utopian ideal if it claims to be free from the powers that rule the world. The visual vocabulary during the decade of the economic boom is essentially advertising by virtue of the performative will acting on every creative sphere (starting with Pop Art, to which Armando Testa will almost immediately offer a “narrative” as opposed to the simple idolatry of the object or message, but icastic, that is, in a broad sense based on abstract parameters). It is difficult to think that one can give up acting outside the schemes that regulate media powers. Armando Testa, as early as the 1940s, toward the end of the war, operates as one of the most incisive “reconstructors” of a graphic and advertising language that already had some brilliant communicators and designers in the years of the regime, however. It should not be forgotten that Testa from a young age wanted to be an artist; and that his inventive talent sprouted from a still autarkic vision of the artistic object (in a certain way, the genius of Bruno Munari corresponded to him, both in playful irony, but also in the design linked to the industrial culture in fieri); finally, while elaborating languages and forms of expression Testa exercised his original predilection for abstract art. He had begun with thears tipographica and then put into practice certain Bauhaus schemes, in an anti-classical logic that determined real architectures on the page (he had trained in Turin following the magazine “Graphius,” to which in Milan corresponded in the 1930s “Campo grafico” where the Modiano-Persico tandem also worked, creators of a parallel vision between page and architecture: “Casabella” was the manifesto of a new graphic design with intentions of augmented communication, but the construction of space became architecture with Persico and Nizzoli’s layouts for the Sala delle Medaglie d’oro and the Costruzione metallica pubblicitaria for the plebiscite, two masterpieces linked to the institutions of the Regime, but also the Negozio Parker, a masterpiece of furniture as Luciano Baldessari’s Bar Craja).

Abstraction and communication Testa had experimented with them on some dialectical pairs of art: Marinetti-Mondrian, but also Caravaggio-Michelangelo and then the seemingly Calvinist minimalism of Mies van del Rohe, where “the less is the more,” but which for the German architect stemmed from meditation on the objective realism of Thomas Aquinas, that ofadequatio rei et intellectus.

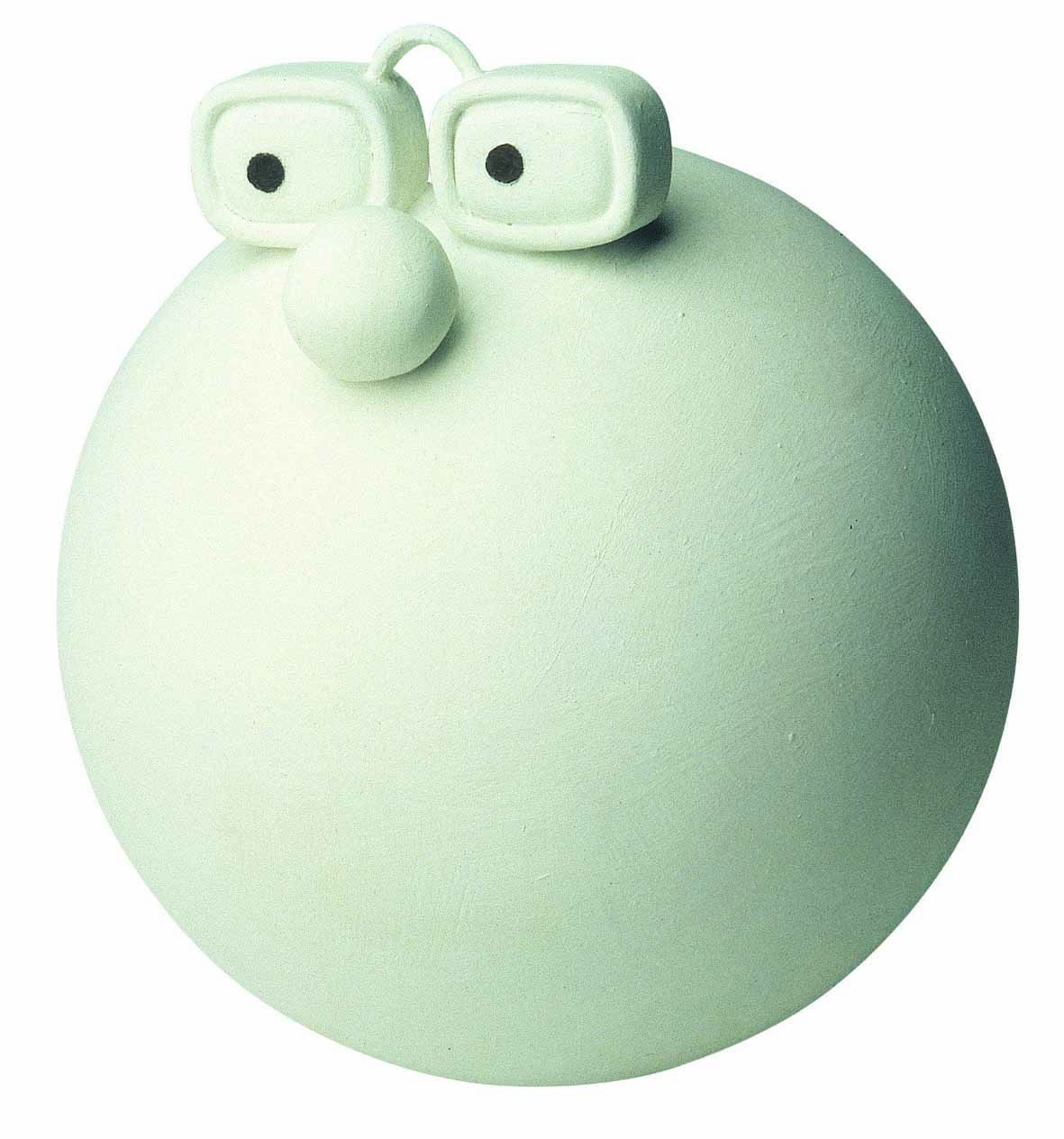

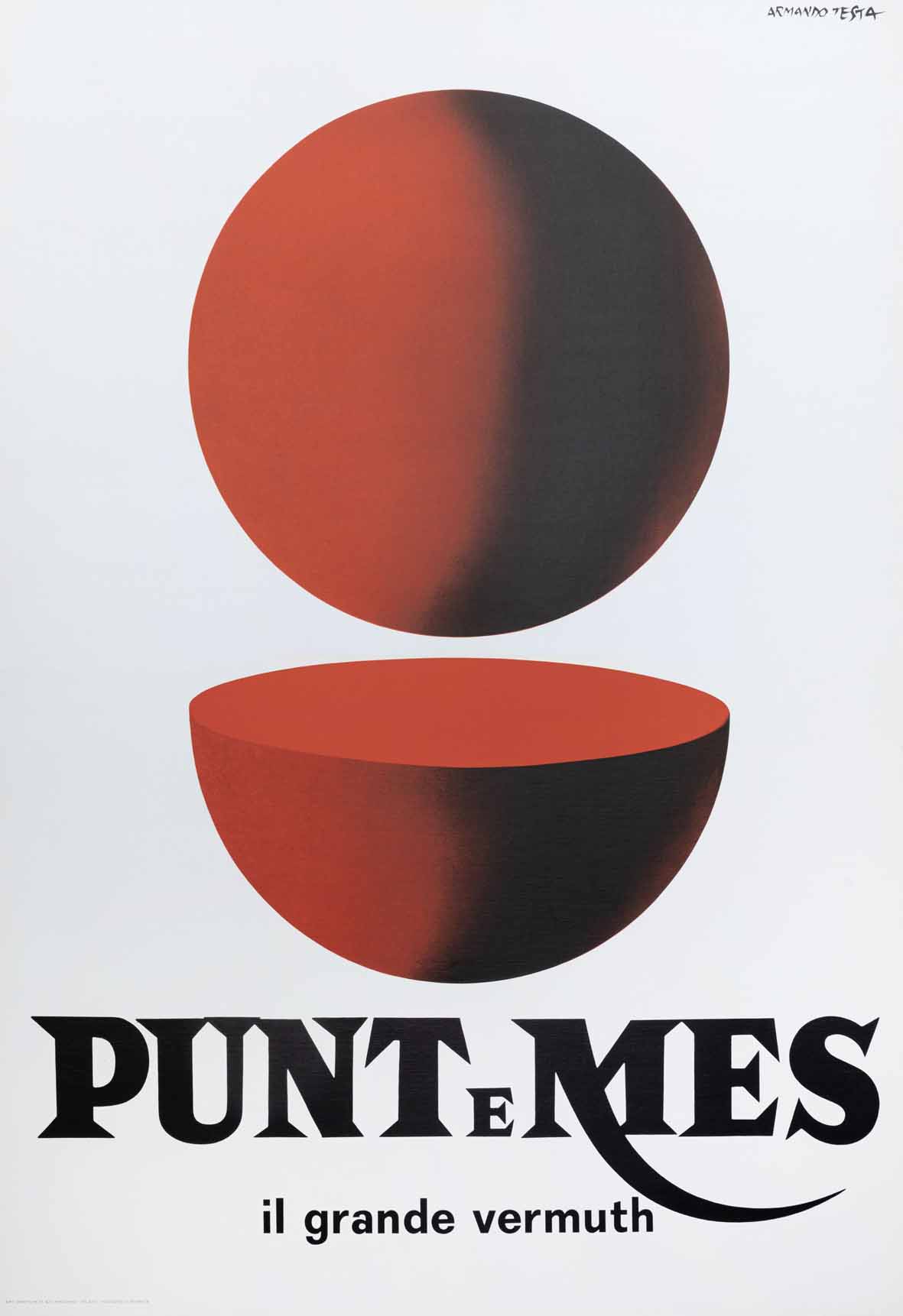

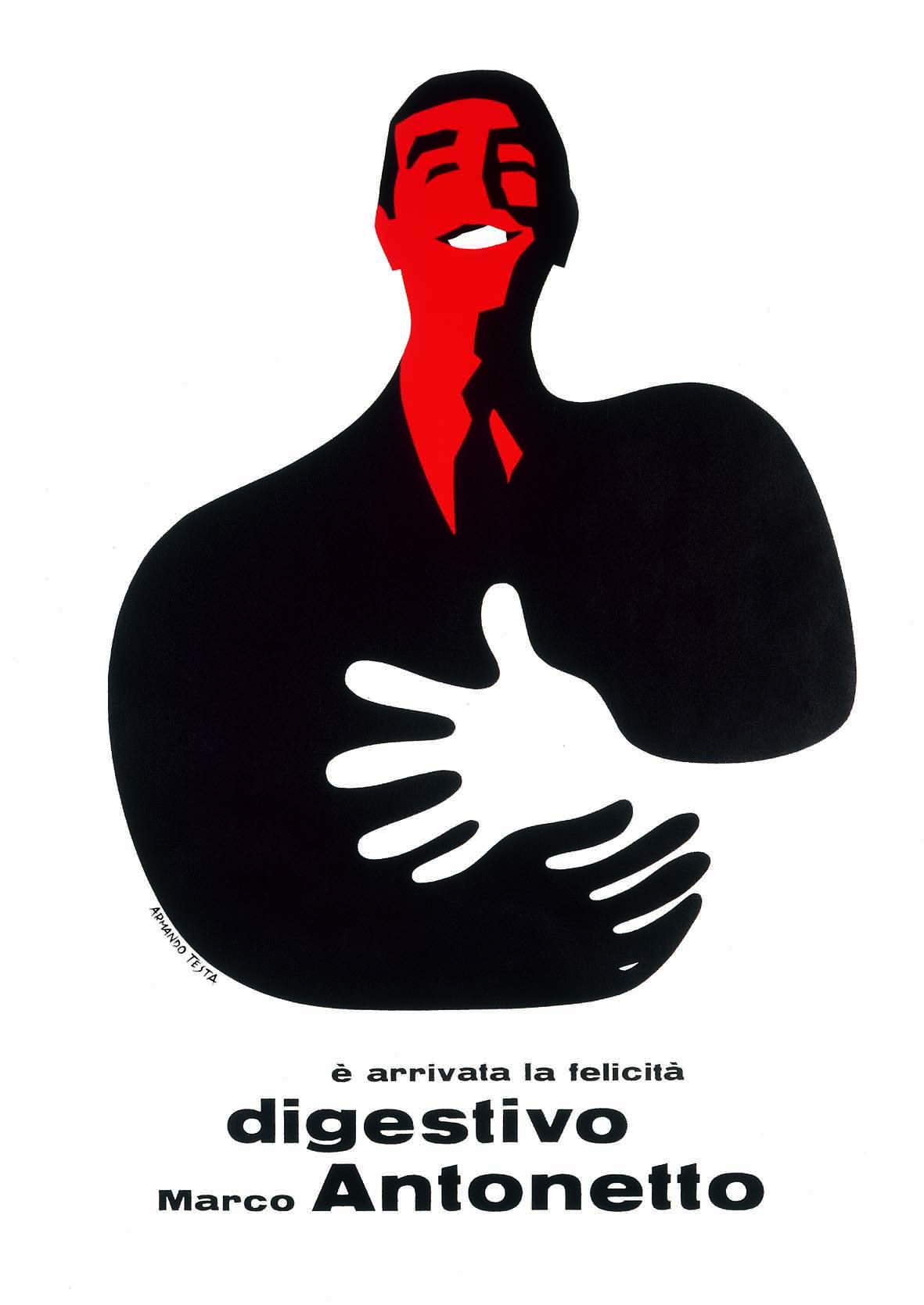

Making painting, sculpture and typography a triad at the origin of his advertising vision, Testa entered the Italian scene with his overbearing talent, first producing billboards (his was the one for the 1960 Olympics), but then following up-after founding Studio Testa-a series of brilliant inventions that spoke precisely to the new Italians who aspired to participate with their choices in the country’s overwhelming rise: Caballero and Carmencita, Papalla, Punt e mes, Pippo the hippopotamus, to the over-ironic King Carpano, a sort of ever-smiling fool who toasts with a bitter grimace along with the characters in the story; and again the beautiful figure of the man advertising the digestive Antonetto, who massages his gastric system expressing a sense of physical well-being, whose silhouette in black and red stands out against a white background: “that very neutral base, like the primer that prepares a canvas for the painter,” Tim Marlow notes in the catalog (Silvana), “was a ’radical’ choice for those times. Testa since these iconic masterpieces poses himself as a great alphabetizer of Italians: of course, one would have to wonder if the slogan for the Paulista café ”Carmencita you’re already mine, turn off the gas and come away" is still palatable to the female world because of the subtle and ironic machismo of the caballero, witty but resolute, who kidnaps his lover with a momentum that subjugates gender. Themes that resurface latently in other testian advertisements as well, from that of the Peroni Carousel to that of Olio Sasso.

The great publicist walked with Italy. In the late 1970s, for example, he anticipated the Eat turn in art (with Spoerri). But his ham chair or the “division of mortadella,” or even the popular sausage that acts as a tablecloth for a table on which rests a block of emmenthal in the shape of a television set, are amusing ideas that play with the sociological mainstream of the time, yet without striking a unique and unrepeatable chord in the way Meret Oppenheim’s Breakfast in Fur had done half a century earlier. In this case, publicity was the object, indirectly, of sacrifice in favor of art itself.

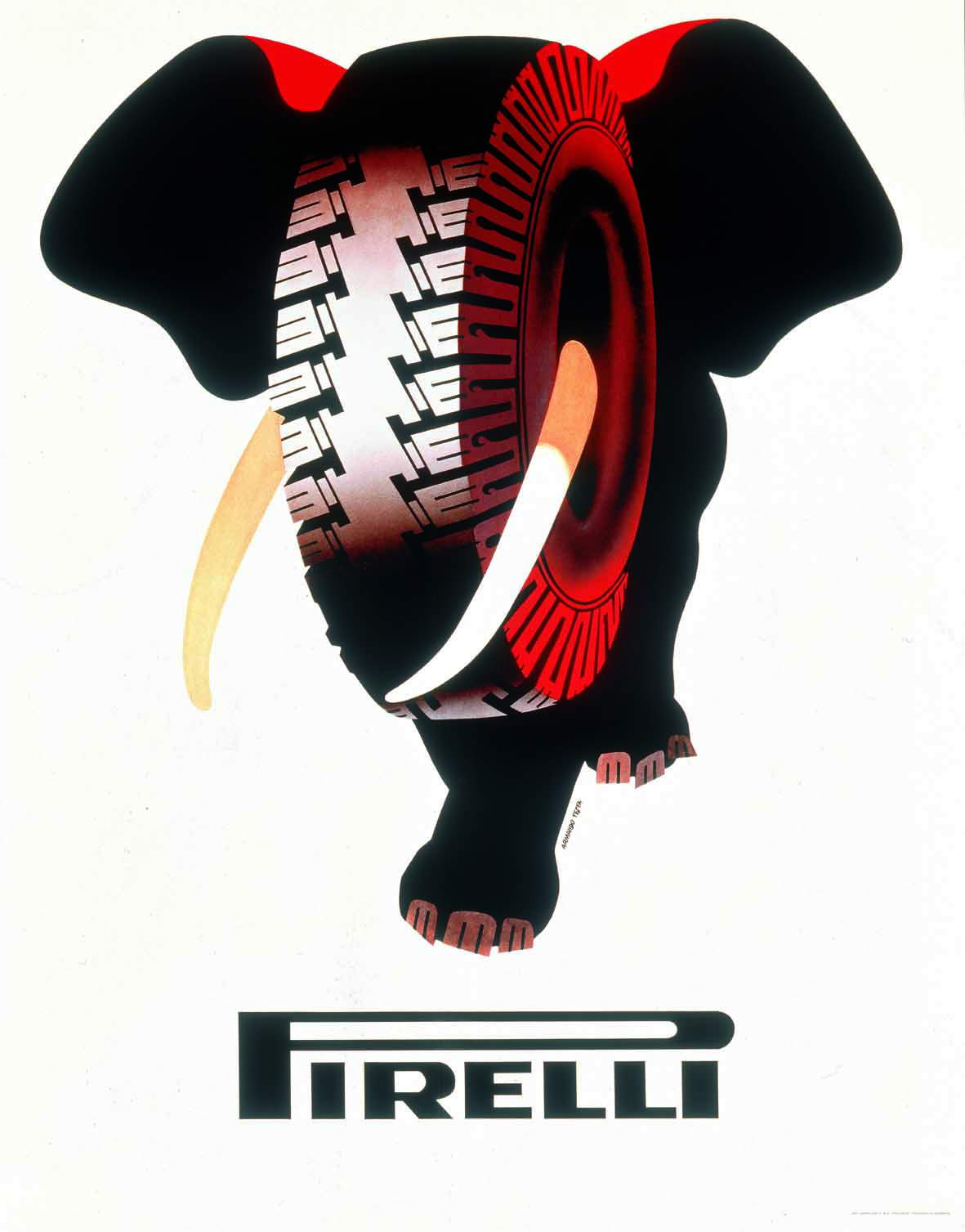

The exhibition set up in these weeks at Ca’ Pesaro until Sept. 15, which follows by about a year the important donation of contemporary art made by Gemma De Angelis Testa, is designed to make the visitor understand the author’s indomitable artistic propensity, his pictorial and plastic vocation - as a painter by vocation, he will sometimes go so far as to use imprimitura as the structural color of the work -, where his technical skills, although through a very conscious formal control, however, do not always have the same creative burst that determines advertising and graphic research. Gemma de Angelis Testa emphasizes the multidisciplinary iter that governed her husband’s research, seeing in this versatility of means the access to a modernity that is still relevant today. “Juggler of the image,” that is, exemplary of the renewed culture of the 1960s, Testa did not repudiate an Italian tradition of the interwar years (evidence of this is the building he designed in the 1980s for his own agency, a red parallelepiped perforated with large windows all the same, between metaphysics and postmodernism, between Sironi and Aldo Rossi); precisely because of this Testa has accomplished a feat that places him as a refounder of the imaginary of a country that is a candidate to be part of the industrialized world sustained by the production-consumption ethic, and with awe-free advertising he accomplishes the miracle of uniting, we might say, Protestant rigorism and Catholic aesthetic form. A marriage that also led him to be a “normalizer” of Italian genius with respect to the great wager of progress that passes above all through advertising campaigns linked both to products (Sanpellegrino bitter, Nastro Azzurro beer, Pirelli tires) and to cultural and mass events (the Olympics and Einstein’s centenary), that is, to social battles against world hunger, for the poor, in favor of divorce, in support of dissent in Eastern countries or for Amnesty international. The sign that most emblematized Testa’s allusive genius was the Punt e Mes symbol, which was multiplied in various ways (Painting, advertising image, object, shape play) until it fell into the almost fetishistic mannerism of the giant black reflective steel sculpture placed in the new Porta Susa AV station in Turin. The Venice exhibition closes with a series of crosses all executed taking inspiration from the iconography ofreclinatio capitis (a Christian symbol that has even determined the floor plans of some churches with the axis of the apse tilted to the left, as at Santa Prassede in Rome). The cross with the sloping “vertex,” almost a syllogism taken in the very form of the object: abstraction, narrative, synthesis. Here is the formal law by which Testa measures himself.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.