The Splendors of the Farnese Collection. What the Capitoline Museums exhibition looks like

“All the statues of marble and metal and of every other matter, the office of the Madona illuminated in gold by the said Giulio Clovio et all his libraria in his palace in Rome from whence they cannot be moved or lent or sold or alienated in any way”: this was the wish of Grand Cardinal Alessandro Farnese regarding his precious art collection. According to his wish, the Farnese Collection should never have left the Campo de’ Fiori Palace in Rome (now the seat of the French Embassy in Italy) and both works and objects should have remained inalienable. But not much time passed after the aforementioned will (1587) and the death of the Grand Cardinal (1589), because already after 1600 part of the collection left Rome to be transferred to Parma and Piacenza following the appointment as Duke of Parma and Piacenza of the latter’s heir and brother, Ranuccio Farnese. And later, in the 1780s, other pieces from the collection were transferred to Naples at the behest of Ferdinand IV, son of Charles of Bourbon, who, as he in turn was the son of Elisabetta Farnese, the last heir of the Farnese family, took under his control both the inherited Duchy of Parma and the conquered Kingdom of Naples. It is for this reason that many works that belonged to the Farnese Collection are now in Naples, between the National Archaeological Museum, the Museum and Real Bosco of Capodimonte, and the “Vittorio Emanuele III” National Library.

It should be emphasized, however, that the heyday of the Collection, considered among the most beautiful and prestigious of the Renaissance, dates back to its Roman period, from the early 16th century to the early 17th century, under the tutelage of its initiator Alessandro Farnese, the future Pope Paul III (from 1534 to 1549), and his heir and successor, Grand Cardinal Alessandro. This is precisely the intent of the exhibition The Farnese in Sixteenth-Century Rome. Origins and Fortune of a Collection, curated by Claudio Parisi Presicce and Chiara Rabbi Bernard, which can be visited until May 18, 2025 at Villa Caffarelli in the Capitoline Museums: to immerse the public in the moment of full splendor and enrichment of the Farnese Collection and to tell the story of its connection with Rome. The result is a harmonious and pleasing exhibition project that winds its way through twelve rooms, featuring 140 masterpieces, including ancient sculptures, bronzes, paintings, drawings, manuscripts, gems, coins and archaeological finds from the Neapolitan museums now custodians of a conspicuous part of the Collection, from museums in Rome, Florence and Parma, as well as from France, Britain and New York. Certainly outstanding are the first pictorial and then sculptural portraits of Pope Paul III, respectively by Jacopino del Conte and Guglielmo Della Porta; ancient statues, particularly of Pan and Daphni; preparatory drawings for the frescoes in the Carracci Gallery; theEros Farnese, the Sottocoppa della Tazza Farnese with Sileno ebbro (the Tazza Farnese often leaves during exhibitions the Museo Archeologico Nazionale in Naples where it is usually kept, but in the Roman exhibition it is not present: formerly in the Medici collections, the masterpiece of Hellenistic glyptics entered like other works from the Medici collection into the Farnese Collection thanks to Margaret of Austria who, left the widow of Alessandro de’ Medici, went on to marry Ottavio Farnese). Also, Raphael’s Madonna of Divine Love , the Book of Hours illuminated by Giulio Clovio for Cardinal Alessandro Farnese from the Morgan Library in New York, and the very precious Cassetta Farnese, a gilded and worked silver casket commissioned by Grand Cardinal Alessandro.

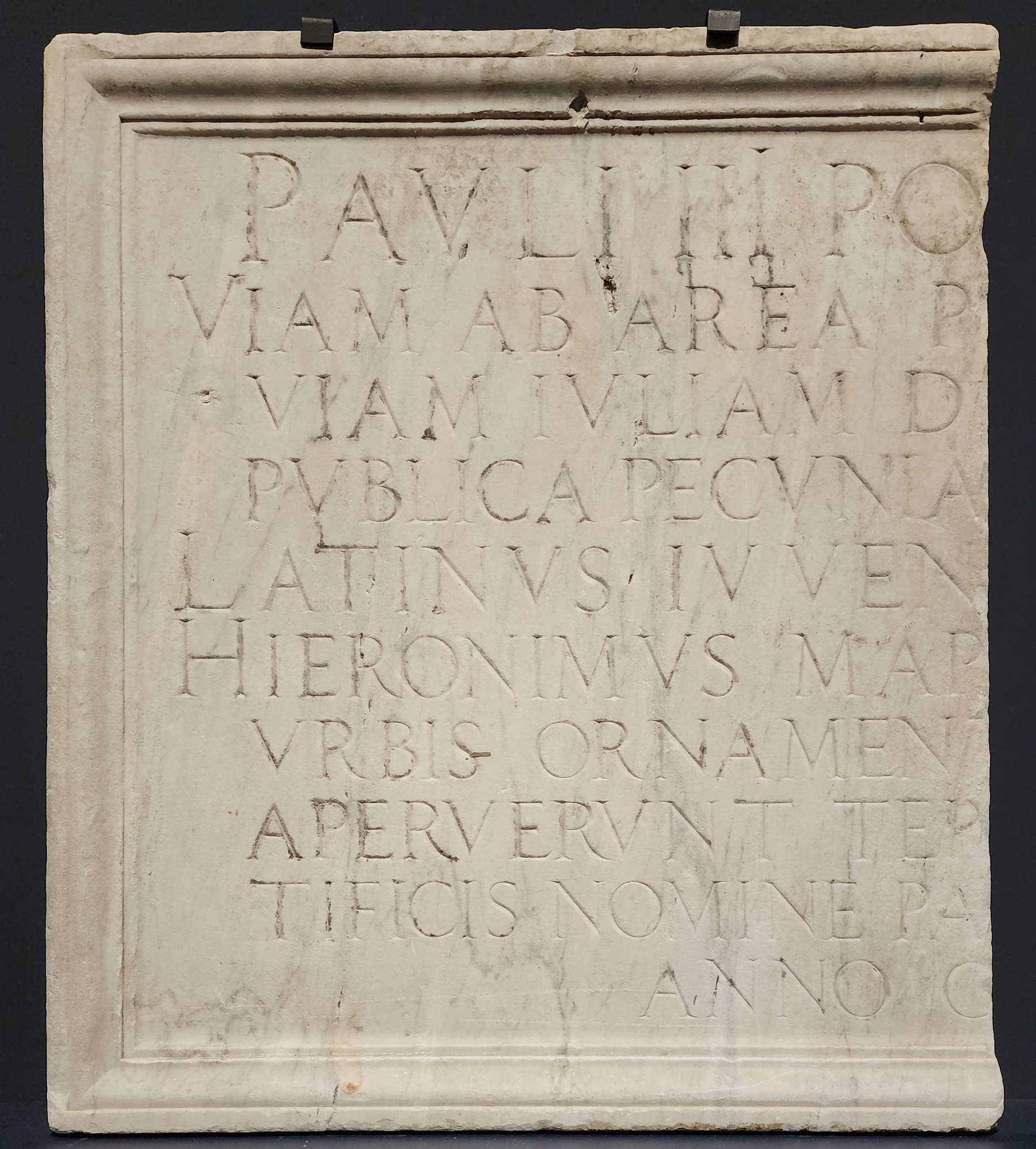

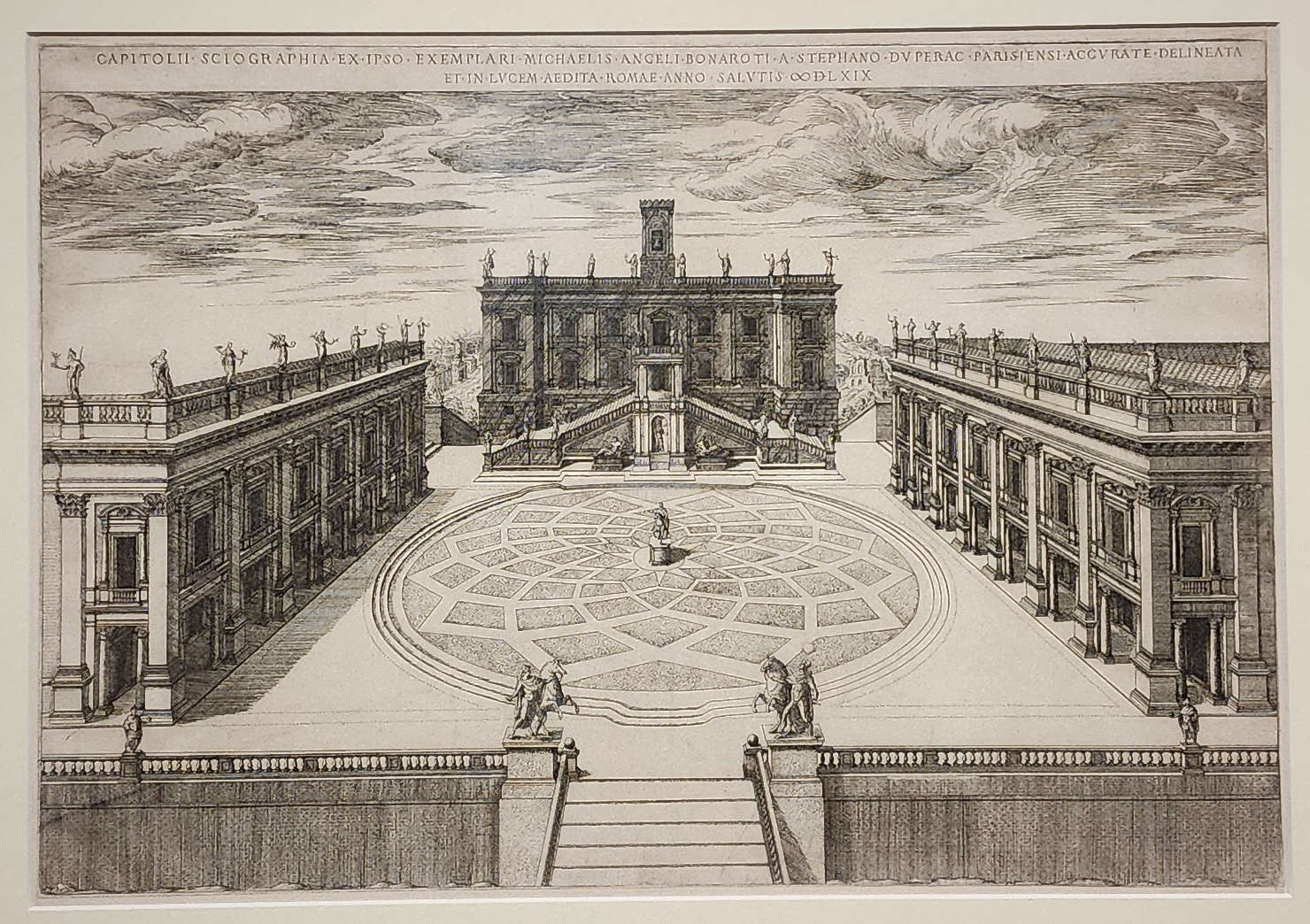

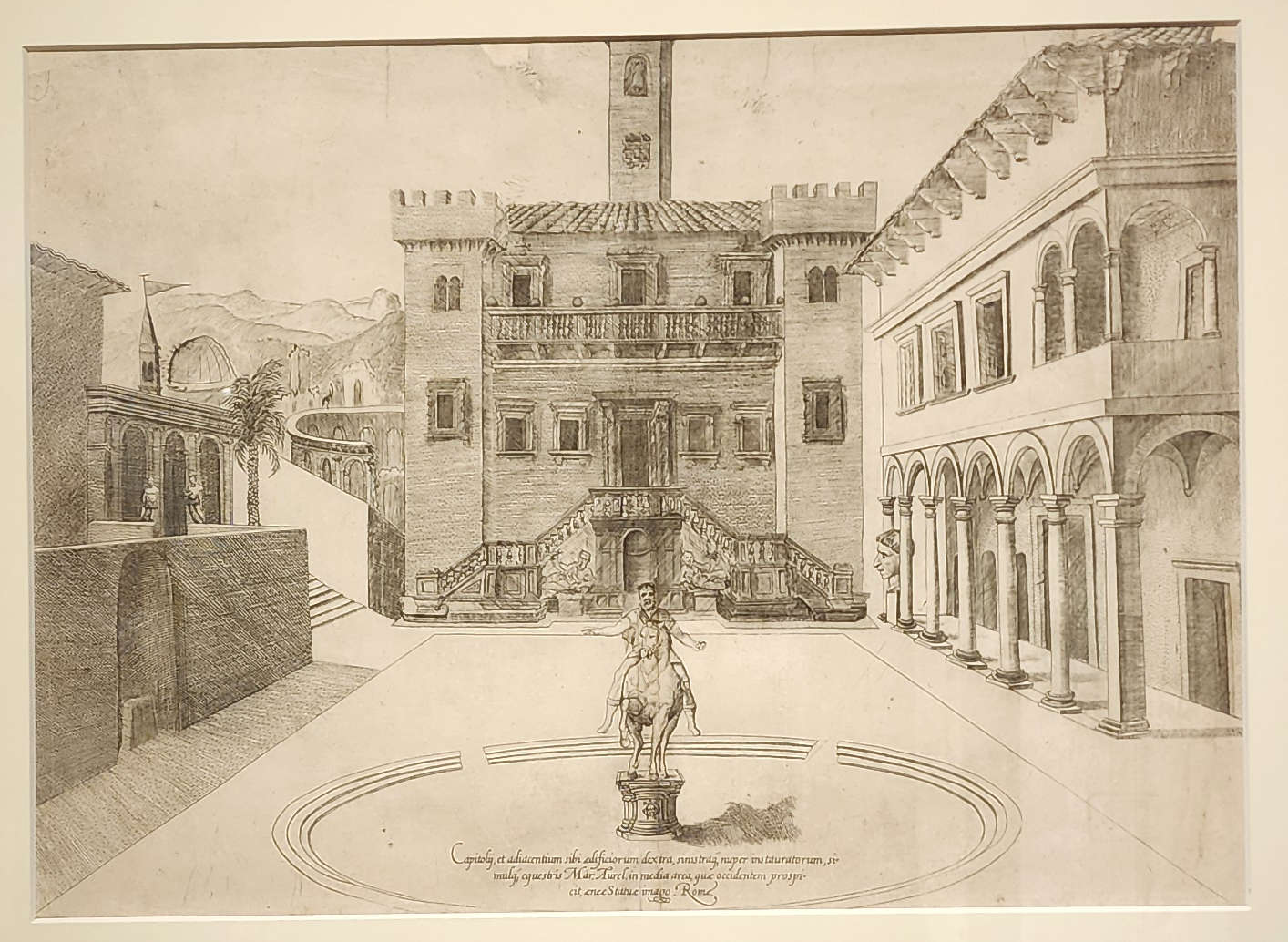

Greeted at the entrance to the exhibition route by Jacopino del Conte’s Portrait of Pope Paul III, it is curious to note that the exhibition in theyear of the Jubilee 2025 kicks off precisely with a Jubilee, that of 1550, in preparation for which Paul III, whose bust completed by Guglielmo Della Porta stands out on the back wall of the room, promoted a series of urban interventions that changed the face of Rome (a 1555 map from the Museum of Rome illustrates the chronology), some of which had already begun for the arrival in the city of Emperor Charles V in 1536. Notable among these interventions are the relocation of the equestrian statue of Marcus Aurelius from the Lateran to the Capitoline Hill in 1538 (on display commemorated with a small bronze statue from the Museo Nazionale del Bargello), the commissioning of the Capitoline Hill redevelopment project to Michelangelo (here it is interesting is the comparison between a print by an anonymous 16th-century artist depicting the Piazza del Campidoglio before Michelangelo’s redevelopment and the print by Étienne Dupérac depicting the same Piazza according to Buonarroti’s project), and the opening of the Via Paola in 1543 (the only surviving fragment of the original epigraph of the work to open the street named after the pontiff is on display). All the protagonists of the Farnese family who contributed to the birth and enrichment of the precious Collection during the Roman period are brought together with their portraits in the next room, preceded by the famous gilded lily that in a family tree reconstructs the noble dynasty, from Paul III to Elisabetta Farnese: there is Alessandro Farnese future Pope Paul III in his cardinal robes depicted by Raphael and in papal robes with camauro and breviary depicted by Titian, there is his nephew, Grand Cardinal Alessandro, portrayed by Perin del Vaga, and then there are the portraits of the latter’s brothers, Ranuccio and Ottavio, the latter next to his wife Margaret of Austria, and finally Odoardo depicted by Domenichino.

Symbol and place of the family’s prestige and power was Palazzo Farnese, where the Collection found its space: the following rooms are therefore meant to be a glorification of the building both from an architectural point of view (some drawings of the entire Palace, the Courtyard, and the second floor are displayed here) and as a “container” of ancient statues that adorned the different rooms and precious objects that gave even more luster to the family. At the center of the first of these rooms isEros riding a dolphin, a statue that was encountered in the atrium that opened at the end of the first flight of the palace’s staircase of honor; drawings and bronzes of theHercules Farnese and a miniature reproduction, also in porcelain, of the Farnese Bull, or the two monumental statues that were placed in the Great Courtyard and were found during excavations at the Baths of Caracalla in 1545-1546 (there is also a detailed marble bust of Caracalla). Also prominent in these rooms are the sculptural group of Pan and Daphni, from the late second century AD, accompanied by a study by Annibale Carracci of the satyr’s head from the Louvre in Paris, the small bronze with theHercules as a boy choking snakes by Guglielmo Della Porta, and the aforementioned Sottocoppa della Tazza Farnese with Sileno ebbro, a refined silver plate engraved with a burin made on commission from Odoardo Farnese by Annibale Carracci. These are all works that testify to the Farnese family’s passion for antiquity.

We continue by emphasizing the rooms of the palace with the Gallery: in the center of the exhibition room is reproduced on one floor the vault frescoed by the Carracci with mythological scenes inspired by Ovid’s Metamorphoses, at the center of which stands the Triumph of Bacchus and Ariadne; on the walls we have the opportunity to admire the preparatory drawings of some details of Annibale Carracci’s frescoes and five of the ten sculptures that in the Gallery were placed inside niches: the so-called Antonia, Dionysus, Ganymede and the eagle, theEros Farnese, and the splendid sculptural group of the Satyr with Child Bacchus; the latter returned to Rome on this occasion after moving to Naples in the last decade of the 18th century. And immediately afterwards follows one of the Great Cardinal’s favorite places, the Hall of the Philosophers, a section devoted to Venuses, in which stands out the beautiful and sensual Aphrodite Callipigia, a copy of the Hadrianic age kept at the National Archaeological Museum in Naples, who, lifting with both hands the draperies of the dress she wears, uncovers with a slight twist her beautiful bottom. This was part of a trio of Venuses (the other two are crouching and one of them is on display in the exhibition). Next on display is Pontormo’s large painting with Venus and Cupid from the Galleria dell’Accademia in Florence, which is one of the finest versions of a canvas attributed to Marcello Venusti that the inventories mention in the Hall of the Philosophers.

A special section, however, is devoted to Fulvio Orsini, erudite humanist, philologist, numismatist, epigrapher and collector in his own right, who was mentioned as early as 1554 among the “relatives” of Alessandro Farnese; he was also appointed director of the Farnese library by Ranuccio and later conservator of the Collections, as well as personal secretary to Grand Cardinal Alessandro and then to Odoardo. It was under his supervision that the Farnese Collection became one of the most prestigious of the sixteenth century. This room dedicated to him contains some of the works belonging to Orsini’s collection that entered the Farnese Collection upon his death by bequest in his will, while his books he left to the Vatican Apostolic Library. On display is a specimen of his Imagines et elogia virorum, a cornerstone for the study of ancient iconography that grew out of Fulvio Orsini’s desire to illustrate his own collection. Notable examples from his art collection include the Double Herma of Herodotus and Thucydides in Pentelic marble from the MANN in Naples, the Savior attributed to Marcello Venusti from the Galleria Borghese, and a selection of agate cameos. Also linked to Fulvio Orsini, however, is the Camerino, a small room on the piano nobile of Palazzo Farnese, since he was responsible for the iconographic design of the decoration that was entrusted to Annibale Carracci. The objective was to exalt the virtues of the members of the Farnese family. In the center of the vault stood the painting now preserved at the Museo e Real Bosco di Capodimonte in Naples ofHercules at the crossroads, that is, forced to choose between Vice and Virtue. Thus, preparatory drawings for the frescoes and one for theHercules at the Crossroads in the vault are on display here, as well as the precious Renaissance-era agate cameo that belonged to Orsini and inspired his iconography.

The immersion in the various rooms of Palazzo Farnese in its heyday, which visitors to the exhibition at Villa Caffarelli have a chance to walk through from the room where theEros astride a dolphin is located, continues with the section devoted to the rooms of paintings and drawings: three rooms on the second floor of the northwest wing of the Palace that housed the paintings (more than two hundred), including sacred-themed paintings and portraits, and the most important drawings in the Collection. Thus we find in this section some of the sacred-themed paintings that belonged to the Collection, such as Raphael and helpers’ Madonna of Divine Love (now at the Capodimonte Museum and Real Bosco), El Greco ’s Healing the Blind Born (now at the Pilotta in Parma) and Christ and the Canaanite Woman (now at the Stuard Picture Gallery in Parma), and Annibale Carracci’s Mystic Marriage of Saint Catherine (now at the Capodimonte Museum and Real Bosco).

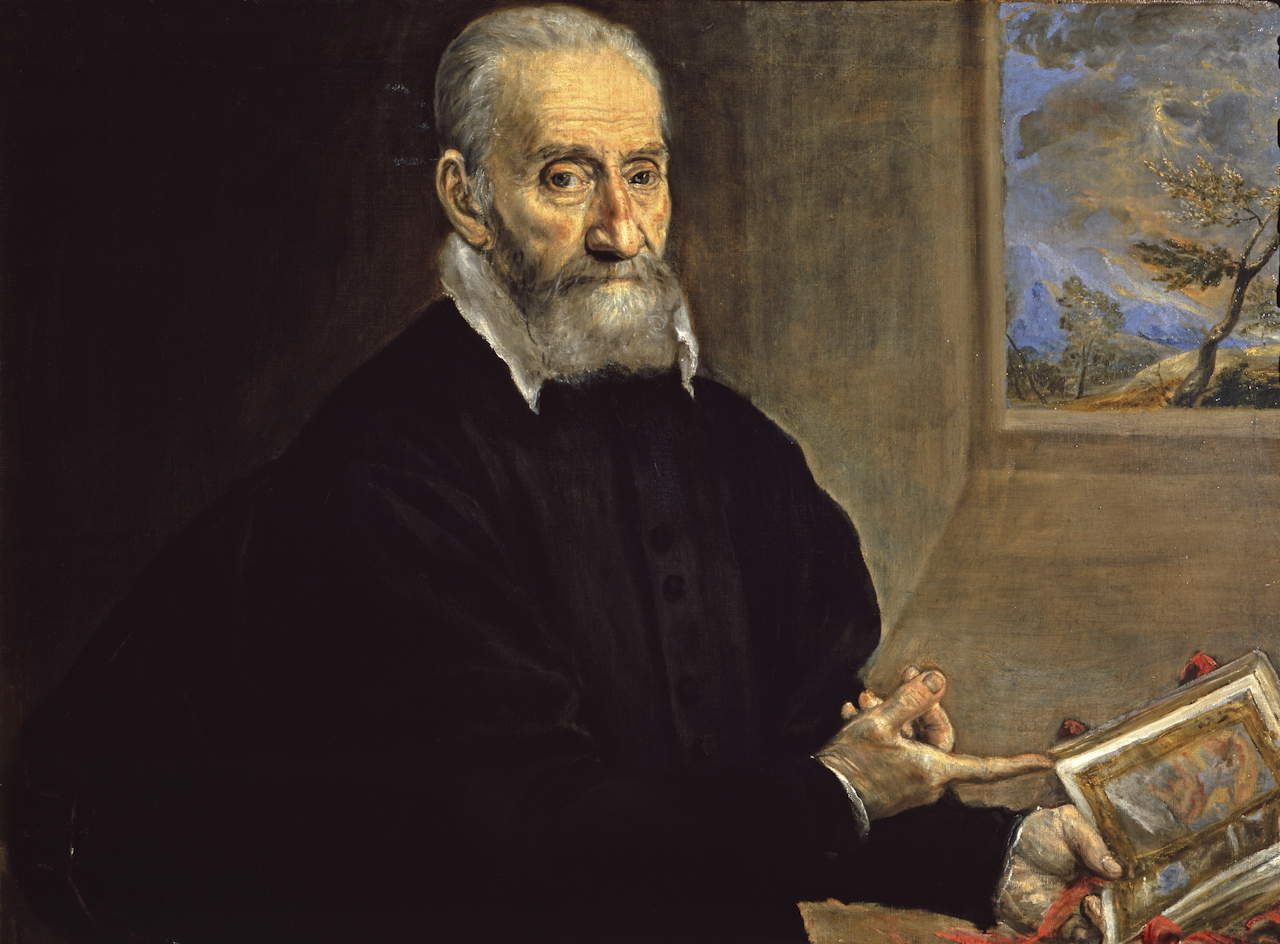

The exhibition concludes with the section entitled Two Collections, One Destiny: the Farnese Collection and that of Fulvio Orsini, which, as mentioned, flowed into the noble family’s collection by will. The section celebrates the union of these two extraordinary collections, but at the same time it also marks the end of the most prestigious period of the Farnese Collection, since this, after the death of Orsini (1600) and the death of Odoardo Farnese (1626), would head towards a slow decline and subsequent transfer from Palazzo Farnese and Rome, thus not respecting the wishes of Grand Cardinal Alexander. Note the curators’ finesse in juxtaposing the Portrait of Julius Clovius holding the Book of Hours, a painting by El Greco that belonged to Orsini’s collection, with the same Book of Hours depicted in the work and displayed open to the same page. The Book of Hours illuminated by Giulio Clovio (whose self-portrait is also on display in the exhibition) is back for this exhibition event for the first time in Italy since its sale to the Morgan Library in New York. In the center of the latter room then makes a fine display of the marvelous and very famous Cassetta Farnese.

The Farnese in Sixteenth-Century Rome. Origins and Fortune of a Collection thus offers an opportunity to understand the prestige of a family that linked itself to Rome through important urban interventions that changed the face of the city and at the same time gave birth to one of the most important collections not only of the Renaissance but of all time. A triumph of ancient statues, precious objects, gems, paintings, and drawings brought together in a single palace, itself decorated and frescoed by great artists of the time. The history of the Collection is told here from its beginnings to its decline, hand in hand with the splendor of a family that in Rome knew its peak but also its end.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.