The revolution of the circle in Marina Apollonio

The word “abstractionism,” in the arts, is in danger of being a meaningless word. And not because, conversely, “figurative” makes sense. On the contrary. It is a confusion that came about with the avant-gardes who, having faith in the new, considered the forms of art that tradition had handed down to us until almost the end of the nineteenth century a burden to be removed in favor of total freedom. Destroying was a kind of denial of the defining principle of myths: they serve to recount something missing from our historical consciousness, they cure an amnesia concerning the origin of a story(in illo tempore). If abstraction along the twentieth century was also a kind of hyperbaric moment, of purification from the dross of the past, on the other hand, the tabula rasa introduced through the window what had been put outside the door. Catastrophe theory, on the cultural-historical level, is nothing more than this: to destroy in order to continue, Aufhebung, a situation we inherited conceptually from Hegel, who thus defines the essence of the dialectic, the standing together of opposing meanings, but also from Nietzsche, who in Zarathustra sees it as the necessary step: that is, first destroy in order to then rebuild. This, in the end, is one of the cardinal principles of nineteenth- and twentieth-century modernity. And abstractionism represents that new beginning (catastrophe, precisely, with respect to the tradition of art). An origin that is not handed down to us by history, but by an act of foundation, the new precisely, whose rules, as in the avant-garde, are set by the subject who celebrates this recommencement as a gesture that surpasses all previous legacies. Abstractionism, in art, became its ideology, reflected in a conceptuality that by appealing to science, mathematics, and lyrical autonomy from any representation of meaning, allows the total expression of the human imagination in a realm of pure immanence, no longer seeking justification in a space beyond the visible, in transcendence. The spiritual in art is this possibility of finding the beyond in time, that is, in real life.

Having overcome all in all in a relatively short time, a decade or so, the diatribe between realists and abstractionists that had already become apparent during the Ventennio without, however, reaching the conflictual levels of the Postwar period, where ideologies threw gasoline on the fire, all the premises that provided an identity to the two factions, and the various subgroups, turned out to be untenable in light of the fact, as obvious as it is self-evident, that the very category of formlessness, dear to the existentialism of non-being, tends precisely not to non-form, but to a form of the formless - a querelle that, on both sides, very soon wore down the same competitors, not least because the risk for all was the politicization of art condemned, as Vittorini said to Togliatti, to play the fife of revolution (a theme moreover addressed by Benjamin in his essay on the Reproducibility technique of art where he highlighted the transition from religious to political value of the work of art and identified a mirror relationship in the relationship between art and totalitarianisms). Soon artists realized that they did not want to be an expression of political thought, since their only end was art and its free expression. No one can think that in the lyrical abstraction, in Wols’ formlessness, there is no form; on the contrary, it accomplishes the heroic descent into non-being, almost a descensus ad inferos or catabasis into limbo where art loses its prerogative of generating something that struggles against the death that all things submit to destruction. Likewise, one will not be able to deny those archaic, archetypal values that make the oval forms of Fautrier’s Otages an example of a deep structure that from the mineralization of the organic lets “something human” emerge. In Wols, the lucid (existentialist) despair of destruction demolishes any claim to anthropomorphism in art (not coincidentally, he illustrated several of Sartre’s works); while in Fautrier, despair becomes archaeologically grounded hope. And, to give a final example, neither does Pollock’s painting deny form; indeed, dripping itself is the principle by which Gestalt is translated into pictorial gesture. And I could continue with another absolute artist of the twentieth century, Rothko, whose spatial, architectural superimposition of colors offers the purest and at the same time most real distillation of abstract form that becomes inhabitable through mystical intuition. Rothko is, in fact, the painter who peremptorily and magically rejects the loss of aura prophesied by Benjamin: more than any other, in fact, his painting distances itself from technical reproducibility. And it reaffirms the uniqueness of art.

Under what idea of abstraction, then, is the work of Marina Apollonio, whose important anthology is being presented by the Guggenheim Collection in Venice until March 3? The daughter of Umbro Apollonio, an important postwar critic who directed the Historical Archives of the Venice Biennale, Marina in fact belongs to the time following the aesthetic rethinking of the mid-1950s-which also marked Rossellini’s declared end of neorealism in 1954-where, having overcome (more from mental fatigue than from overt victory) the useless polemics between realists and abstractionists, a search for the “scientific” foundations of art, in the optical and perceptual dimensions that open the mind to timeless forms without representational meaning, became established between the 1960s and 1970s. It is an immanent metaphysics, by paradox, that leans on the deep structures of gestalt research, on archetypes that act, Warburg would have said, as mnestic traces, memories sedimented in human evolution, and on their stratifications that reveal themselves to be more complex as the research on forms and interactions through light and color becomes a kind of descensus in profundo.

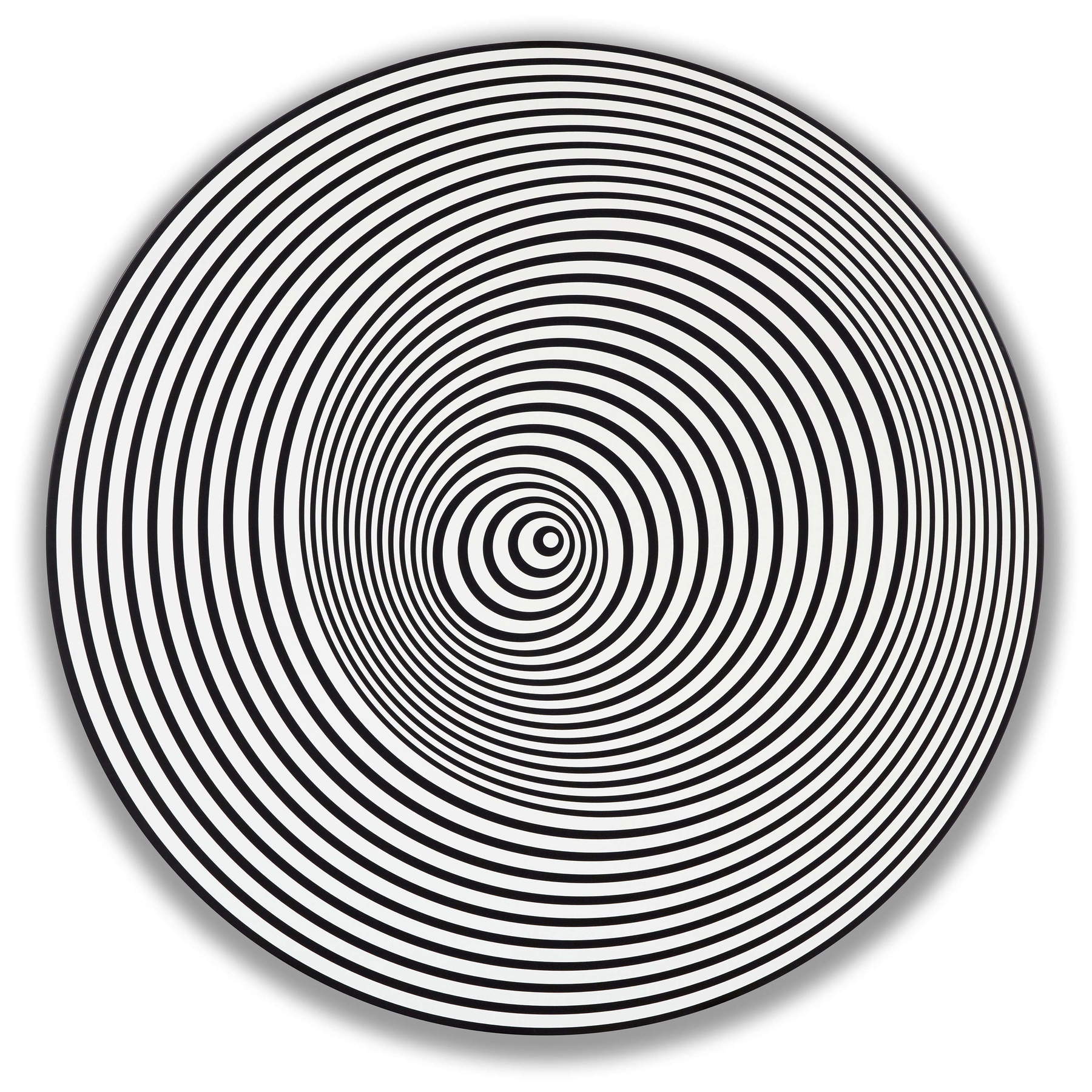

Before going into the specifics of Apollonio’s work, it should be noted that her abstractionism has no direct link to the lyrical abstractionism theorized by Carlo Belli with the “manifesto” Kn that fueled the research of artists such as Soldati, Veronesi, Reggiani, Radice, Rho and others. Compared to this lyrical abstractionism, Marina Apollonio looks elsewhere, for example to the Marcel Duchamp of the 1926 short film Anémic cinéma, or to the Rotoreliefs of 1935, which twirl to create hypnotic spaces, works that Duchamp called “divertissements visuels.” As the curator of the exhibition, Marianna Gelussi, also notes, Marina Apollonio’s attitude, still at the age of 84, is jovial and playful, her ironic and gentle gaze representing her. A way of being that belongs to the spirits whose work -- made up of thought, imagination and numbers -- makes possible a space free from what we might call the friction of time, which acts on us as a tragic abrasion.

Already St. Augustine had explained that time is an elusive chimera. And it is quite amusing that in the Confessions he begins to talk about time by starting with the question: what did God do before he devoted himself to creation? But isn’t God beyond all measure and therefore also beyond time? Augustine knows that the chimera has three faces: a past that is now no more, a future that is not yet, and a present that flows away into the past. Yet, if we talk about it, it means that somehow those intervals exist: “We perceive the intervals of time, we compare them with each other, we define these longer, those shorter,” and the measurement of time makes it “our perception.” So that present, past and future are in our psyche, but are not in themselves. Augustine anticipated by fifteen centuries the great French philosopher of consciousness, Henri Bergson, who in discontinuity from the perennial flow of things sought to define the time of existence. Evidence of both the non-linearity and non-progressiveness of historical development, as the vital impulse that manifests itself in freedom,élan vital alters the temporal continuum of chronological time, like an existential conatus that intersperses the forma fluens.

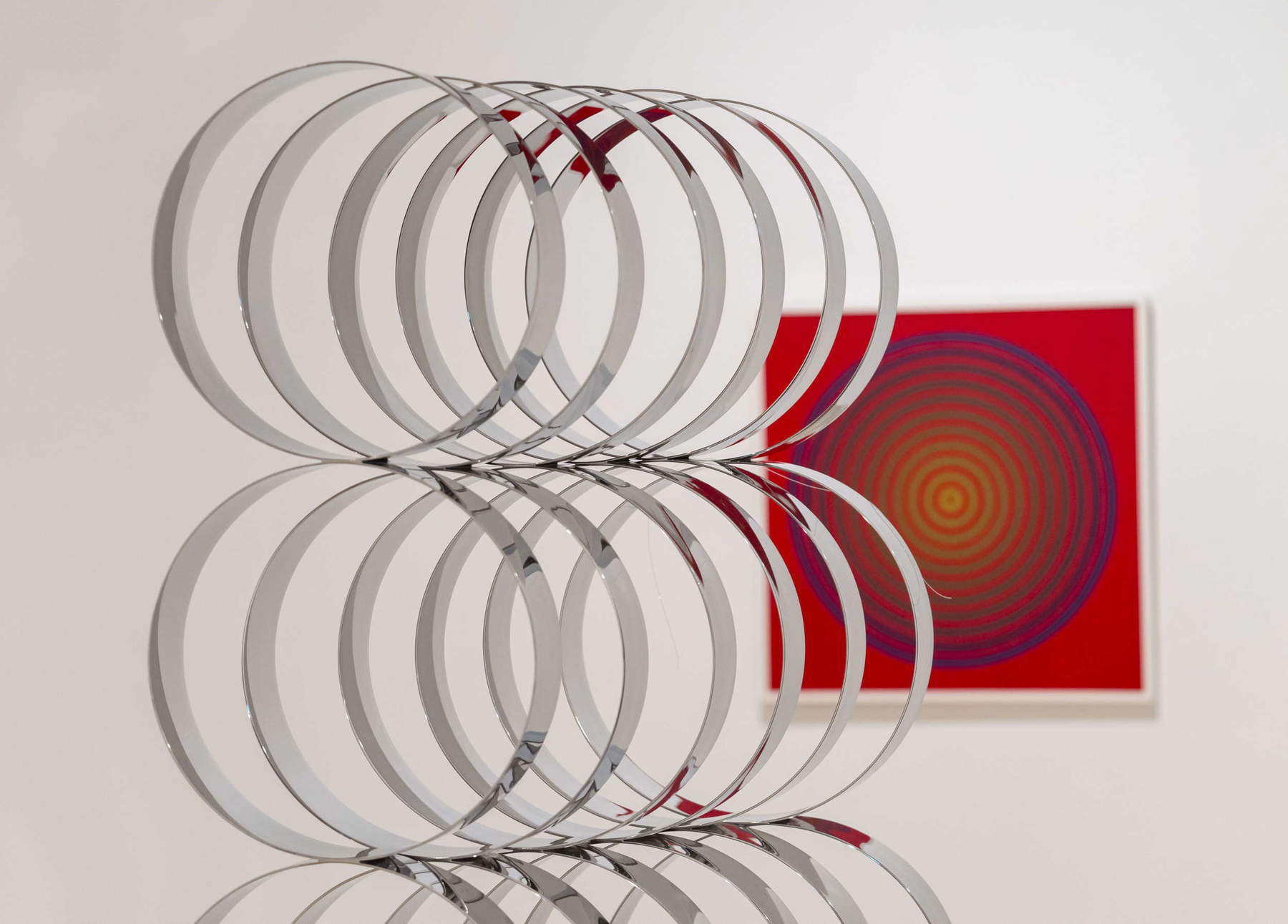

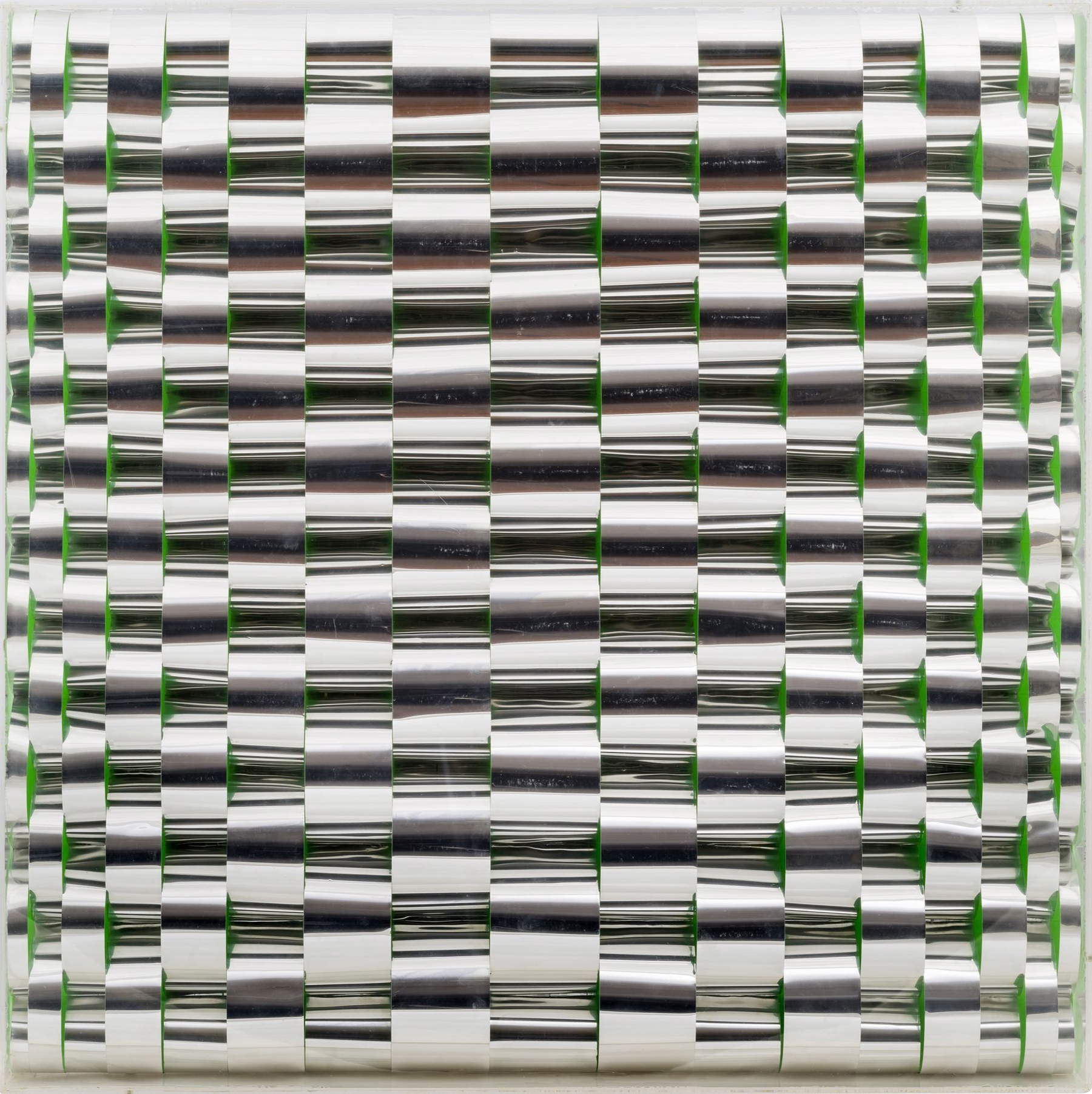

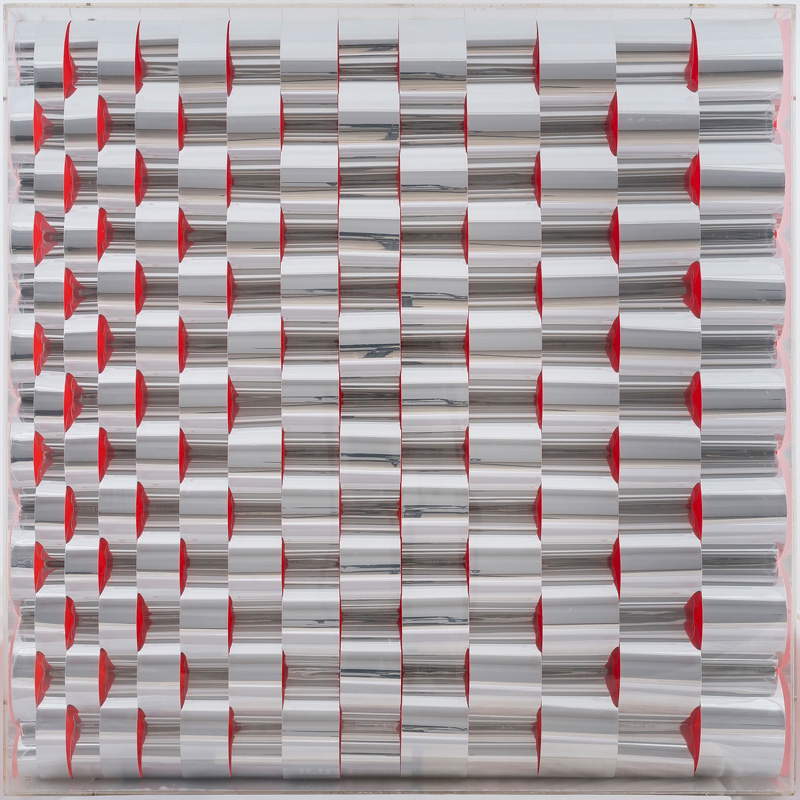

The Guggenheim Collection exhibition, already in its title Beyond the Circle, tells us that we are not in the presence of a closed form. If anything, we are in the presence of an Aristotelian “immanence” and a conceptuality that is in a certain sense Cartesian, since for Apollonio the circle is the condensation of the work that opens toward the viewer, as the Méthode is for the French thinker already philosophy. Apollonio is among the few artists in the Guggenhein Collection still living, and she continues to produce works in Padua where she lives. Her meeting with Peggy Guggenheim took place in 1968, and the American collector commissioned her work Relief No. 505 consisting of interwoven aluminum strips that generate on a painted background a dynamic, undulating surface that captures light.

Although the artist continues to experiment to this day (some recent works are also on view) the season where her work expresses poetic innovation are the 1960s and 1970s; a time, as Cecilia Alemani points out in an interview with Apollonio, where women who wanted to be artists were subjected to male prejudice. The exhibition, therefore, settles a debt by adding a hitherto little-studied tile to the history of Italian and international art of the second half of the 20th century.

Programmed art as intuition on an optical level and verification on the basis of a mathematical system. It was said before Gestalt. It was about resetting “the gap between image and existence,” overcoming what the informal represents, to make visible the continuous becoming of the real. Could it be a way, anguished, of opposing the present; the tragic moment of living that can at any instant end, a conscious reaction to the cyclical and blind upheaval that dominates nature? An escape, in short, from the Nietzschean eternal return of the identical, which is then a declination of the realm of mothers that Goethe places at the end of the Faust gallery.

Apollonio’s artistic story began when in 1964 he won the Golden Nail award in Palermo with Rilievo sbarra 04, now lost. Since the year before, the circle is already his favorite form. I don’t think you can compare Mondrian’s straight line with Apollonio’s curved line, though, as they say in the catalog. Because theimprinting that marks the landing to abstract forms of both of them is very different, and all in all Mondrian’s colored grids always conceal beneath the abstract appearance a reality “of nature” transfigured in its structures and in this way recreated or if you will redeemed in the beauty of a form that goes beyond all immanence thanks to pure lines and fundamental colors.

On the color present in Apollonio’s works, masters of abstraction where color is the foundational or rather ontological element of form are called upon: Josef Albers and Victor Vasarely, while for the plastic-sculptural sphere Naum Gabo and Anton Pevsner. For dynamism and black-and-white forms, another name that seems to have counted, besides Duchamp, is that of Moholy-Nagy (and his wife Lucia, of Prague origin, whose photography had a bearing on the Bauhaus experience, although it is little valued in history books).

The circle, according to Kandinsky, is the most humble but decisive form. And Marina Apollonio has always walked around armed with a compass. That becomes her forma mentis, precisely as the Methode is for Descartes when he thinks. The circle, eternal return yes, but always different, stands out in the catalog. Sort of an interval between structural form and poetic dimension where color leavens the imagination while rotation generates the illusion that leads the viewer to a hypnosis in space.

The first to feel the crisis of Programmed Art was Germano Celant, who had met Apollonio and that art world very early on, and as early as 1968 he broke away from it by launching the wonderful new idea: Arte Povera. The young critic argued that the idea is forged in opposition to the “complex” art of the “abstract microcosm (op),” pop and minimal, which with a “rich attitude” operates within the “system,” “binds itself to history, or rather to the program, and exits the present.” (Celant perhaps wanted to respond in this way to Argan’s Salvation and Fall of Modern Art, which in 1964 denounced, as a critique of the emerging consumer society, the inability of contemporary art to generate real transformation. The utopia of the alliance between culture and the forces of production in industrial society (crisis of design) disappeared. The “death of art” considered by Argan as the development of a new architecture of the system, is the consequence of the persistence of the capitalist mentality that denies, in fact, the possibility of progress that is liberation of the subaltern classes and realization of social equality (will this be why the left from the 1980s to the present has been a “conservative” force rather than a creator of change?).

Programmed Art did not give the impression of being part of that facilitation of consumption that the market needs. It is, in a sense, an oxymoron: playful and difficult, hypnotic and scientific. An immanent form of aspiration to the absolute. And Apollonius confirms, “Programmed Art ... is not the only geometric and well-executed object. Intuition is free, totally free and programming is a consequent fact of operation according to principles of economy and functionality. The non-geometric and the absurd is valid if it is programming.” That is, perfection for perfection’s sake insteril art (likeart pour l’art, it makes it pleonastic and empty).

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.