The reconstruction of the Herrera Chapel: Annibale Carracci is given back his last feat

The facade of the church of Our Lady of the Sacred Heart, so smooth, sober, spartan, rigid in its geometric tripartition, does not say much to the millions of people who wander around Piazza Navona and pass by it without paying too much attention. Yet in the seventeenth century it was one of the most important churches in Rome: in fact, under the nineteenth-century remains of the sanctuary lies the ancient church of San Giacomo degli Spagnoli, one of the cult buildings of reference for the populous and influential Spanish community that resided in the Urbe four centuries ago, and helped determine its fortunes both politically (after all, both the Duchy of Milan and the Kingdom of Naples depended on Spain, and Rome was in the middle) and economically and financially, not to mention culturally. San Giacomo degli Spagnoli then followed to lose importance in parallel with the downsizing of Spanish hegemony in Italy, and by 1830 it was already abandoned by the few Spaniards still living in Rome, who preferred to pray in Santa Maria in Monserrato. That sumptuous church, begun in the mid-15th century, the first Renaissance church in the Eternal City, renovated a century later by Antonio da Sangallo the Younger, later enlarged on Piazza Navona and endowed with two facades, was in an irreparable state of decay by the 19th century: occupied by Napoleonic troops who had damaged it, it was then turned into a warehouse, remained neglected by its community, and was finally sold in 1878 to the French missionaries of the Sacred Heart, changing its dedication. Before that, however, the Spaniards had tried to salvage what could be saved: after closing St. James’ to worship in 1824, they moved the sacred furnishings and works of art to Santa Maria in Monserrato, and decreed to detach the precious frescoes by Annibale Carracci and his collaborators that decorated the Herrera Chapel.

In charge of the transfer of the frescoes was a specialist, Pellegrino Succi, who carried out the work between 1833 and 1835: once detached, the fragments were first placed in the studio of the Spanish painter Antoni Solà (who had informed King Ferdinand VII about their state, thus spurring the Spanish authorities to make a decision on the works), who carried out some retouching in preparation for the more than likely sending of the works to Madrid. The transport took place in 1850, when the sixteen fragments were packed into three crates and shipped from Rome to Barcelona. Since then, nine have remained in the Catalan capital, it is not clear why, the others actually reached Madrid, while the altarpiece remained in Santa Maria in Monserrato in Rome. The chapel’s fragments have been separated ever since, but already a few years ago art historian Miguel Zugaza Miranda, director of the Prado in Madrid from 2002 to 2017, launched the idea of an exhibition that could reunite what was left of the chapel: a dream that finally materialized in 2022, with an exhibition in three locations(Annibale Carracci. The frescoes of the Herrera Chapel, curated by Andrés Úbeda de los Cobos), first at the Prado from March 8 to June 12, second at the Museu Nacional d’Arte de Catalunya from July 8 to October 9, and grand finale in Rome, at Palazzo Barberini, from November 15, 2022 to February 5, 2023.

The exhibition in Rome is thus the same as in Madrid and Barcelona, but at the Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Antica in Palazzo Barberini it has a different flavor, since Rome was the city that saw the birth of the frescoes of Carracci and his: the city thus celebrates the return of a little-known masterpiece, which can now be appreciated all together, albeit for a short time, with its altarpiece, within a structure that offers visitors the suggestion of being in the chapel commissioned by Juan Enríquez de Herrera, an important Spanish banker who had left Savona in 1568 with the aim of moving to the capital of the Papal States, where he opened a bank in partnership with Ottavio Costa from Liguria, another wealthy patron of the arts, known to have been one of Caravaggio’s most important patrons. The chapel in St. James of the Spaniards was destined to become the burial place of Herrera and his family, and was dedicated to St. Diego of Alcalá, because of a vow Herrera had made: he had turned to the saint, begging him to heal his son Diego, who was afflicted with an illness.

The reasons that led Herrera to choose Annibale Carracci in particular are not known in detail: perhaps, the scholar Patrizia Cavazzini speculates in her catalog essay, given also the fact that Herrera was certainly not famous for being a sophisticated collector, “the banker’s choice was perhaps dictated by the desire to secure the most successful painter in Rome at that time” (the Bolognese painter had finished in 1601 the highly celebrated frescoes in the Galleria Farnese: Carlo Cesare Malvasia, after all, had already written that Herrera had chosen him after this work), in view of a “public commission so closely linked to the Spanish monarchy.” Indeed, it should be noted that the idea of dedicating the chapel to St. Diego may also have been dictated by political reasons: the Franciscan had been canonized only in 1588, although very little was known of his life, probably under pressure from Philip II who, Cavazzini explains, “wanted to affirm the prestige and Catholic identity of the nation also through canonizations of Spanish saints.” Twenty-five years of attempts were needed to convince the papacy to give the faithful the first Spanish saint after more than a century since the last one. As a result, it was also necessary to invent a practically new iconography, with the difficulty given by the fact that there were no portraits of Diego of Alcalá: however, this was not an insurmountable problem for Carracci, who with the frescoes of the Herrera Chapel also signed the first, important decorative cycle featuring the Spanish saint as its protagonist.

After the unveiling of the vault of the Galleria Farnese a very busy period opened for Annibale Carracci, although the artist, starting from that fateful June of 1601, preferred to deal more with invention than with execution, as reconstructed in the catalog by Daniele Benati, with the consequence that from now on “a more or less extensive intervention by his collaborators will have to be put into practice. or less extensive of collaborators will have to be taken into account for any work he conducted; but, even where the result will be more modest, one cannot fail to sense the lucid intelligence underlying it and which, as the surviving preparatory drawings confirm, leads to the master.” For the frescoes in the Herrera chapel, the judgment becomes more difficult, although, as will be seen later, the paintings Carracci executed for the Spanish banker were quite successful: the point is that they have come down to us in a precarious state of preservation, burdened by their troubled history, so much so that they present attributional problems of no small magnitude, not to mention the fact that Annibale Carracci’s working method called for the intervention of high-level collaborators who participated in the work together with the master, while still seeking a uniformity of style. We are also still unclear about the chronology of the work: in all likelihood, Annibale Carracci had to begin work on the first drawings in 1602, as soon as he received the commission, but the operational phase on the walls perhaps began later, since at the same time work on the expansion of the chapel began. Add to this the fact that in 1604 Annibale Carracci was struck by a serious illness, probably of a nervous nature, which caused him serious consequences for more than a year. The execution of the frescoes, according to Úbeda de los Cobos, could date back precisely to the period 1604-1605: because the master’s interventions are limited, and because the last payments attesting to the dismantling of some scaffolding date back to the summer of 1606. And because the last work involved the gilding of the stuccoes, it is assumed that the frescoes were completed some time before the latter operation, especially since an invoice from a gilder dating from September 1605 is preserved.

In any case, even looking at the paintings, despite the precarious state in which they have come down to us, it is possible to guess that they were completed quickly. After visiting the first room of the Palazzo Barberini exhibition, where a number of drawings and plans related to both the chapel and the cycle of frescoes are on display (twenty-five in all are known to date), and where we lose ourselves in admiring Gaspar van Wittel’s Veduta di Piazza Navona, arriving from the Gallerie d’Italia in Naples, Pa, where we can observe the appearance of the ancient façade on the Piazza di San Giacomo degli Spagnoli, we find ourselves in the presence of the two paintings, theAssumption of the Virgin and the Apostles around the Virgin’s tomb, which were above the entrance arch of the chapel, thus outside, and which were completed in a very short time. TheAssumption, the result of a collaboration between Annibale Carracci and Francesco Albani, took just five days of work, while the Apostles required eight. According to Úbeda, Annibale Carracci’s crisis probably manifested itself in the short time span between the making of theAssumption and that of the Apostles, where Albani took a few more liberties than the master’s prescriptions: if Annibale Carracci in fact preferred that there be a more accomplished symmetry between Saints John and Peter, Albani on the contrary broke the balance that the master wanted to impose, arranging the figures in a less orderly manner. From that moment on, Albani, Carracci’s most experienced collaborator at the time, would take over the direction of the site.

So one enters the reconstructed chapel and immediately turns one’s gaze upward, to encounter the figure of the Eternal Father who formerly decorated the lantern, the first fresco to be completed, since logic dictated that one should start from the top. Annibale Carracci’s biographers attest that the painter himself began to work on the figure of God, but then gave up because of the fatigue that painting a fresco in such an uncomfortable position entailed, and perhaps also because he had preferred to leave to Albani the task of completing a scene that was placed in the least easily visible part of the chapel: he would therefore have continued by taking care of the frescoes on the exterior, about which we mentioned above, as well as the scenes in the vault, depicting episodes from the life of St. Diego, for which, as anticipated, Annibale Carracci found himself forced to work from imagination, since he was a saint who had just been canonized and therefore lacked an iconographic tradition. For the four scenes, in the shape of a trapezoid, Carracci always collaborated with Albani, dividing the work as reconstructed by Úbeda: the hypothesis, meanwhile, is that Albani’s intervention was planned from the beginning and was not a consequence of Carracci’s illness. “The collaboration,” the curator argues, “was not conceived by the master for complete scenes, two each, or for halves (absurd), but for plans and figures, so Francesco took care of the parts of less responsibility, so that the master could concentrate on the more challenging ones. Illness forced Hannibal to radically alter the initial plan, changing the assignments and allowing other artists to participate in the project.” Albani painted the backdrops of the vault scenes and sketched the figures, which in some cases may have been completed by Hannibal himself, who reserved the most important characters for himself, while in other cases they would only have been retouched by the master. The scenes tell of two miracles and two moments in the life of Saint Diego: here is the Miraculous Refreshment, where Saint Diego, together with a confrere, sees bread, fish, an orange and a pitcher of wine miraculously appear along the road to Sanlúcar de Barrameda, after he had long asked for some food and help from passers-by, without getting anything. On the opposite side we admire San Diego rescuing the little boy asleep in the oven: a little boy, who came home late, in order to avoid punishment from his parents hid in the family’s oven, which was turned on the next morning, however, by his mother who had not noticed his presence. The boy, who had spent the night in the oven, woke up in the flames, but San Diego’s miraculous intervention positively resolved the situation. On the right we observe Saint Diego receiving the Franciscan habit, while on the opposite wall is a depiction of the first important episode in the saint’s life, the alms received by the knight. For this last scene, as well as for that of the Miraculous Rest, Carracci required a specific layer of plaster to work on, while in the other two scenes the work was done in two stages: Albani completed the episodes alone, and Carracci intervened later for touch-ups.

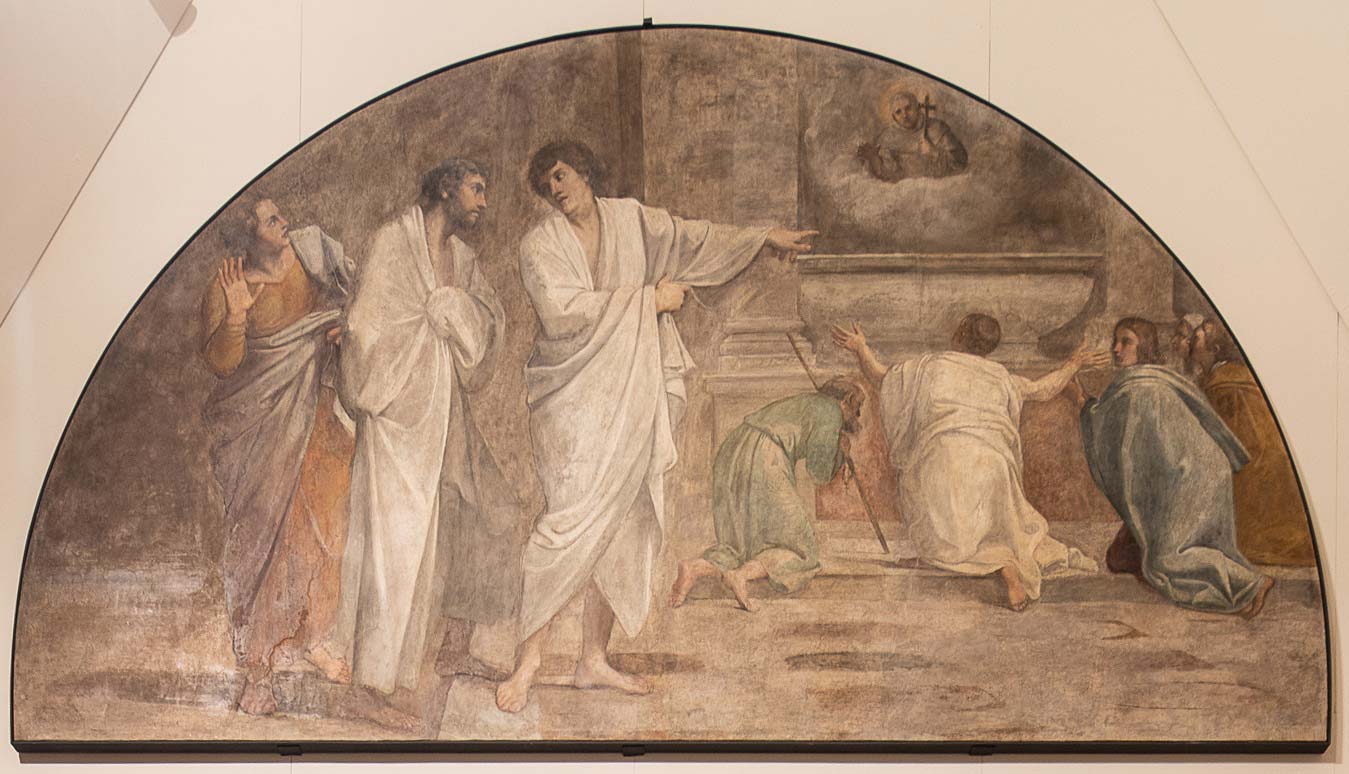

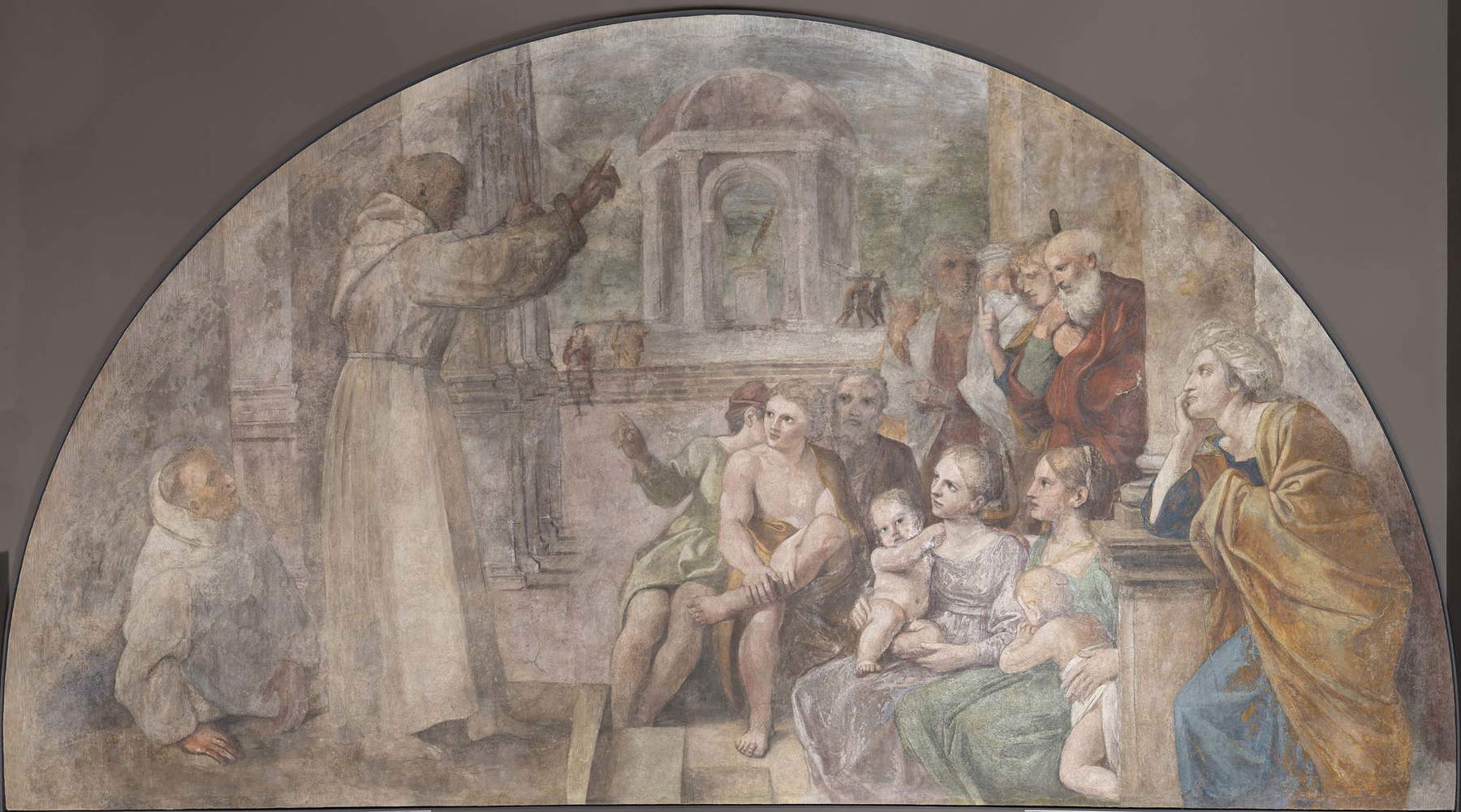

In succession the roundels with saints were made: three survive, which can be assigned to Carracci (the Saint Lawrence, the one that appears to be of better quality), to Francesco Albani (the Saint James the Greater) and to the collaboration between master and colleague (the Saint Francis). They then moved on to the scenes on the side walls, where four more episodes from the life of St. Diego were depicted: on the left, the Miracle of the Roses, a work by Francesco Albani that tells how the loaves that St. Diego was clandestinely distributing to the poor were transformed into roses as soon as he was discovered, and immediately above theApparition of St. Diego at his tomb, a fresco attributed to Giovanni Lanfranco. On the opposite wall, Albani painted the Healing of a Young Blind Man, and in the lunette, in one of the most attributively complicated scenes, we see the Preaching of Saint Diego: a work of Raphaelesque inspiration (in particular, the source is to be found in the cartoon for the tapestry of St. Paul Preaching in Athens for the Sistine Chapel), it is now unanimously assigned to the youngest artist in Carracci’sentourage, namely Sisto Badalocchio, but some parts, especially the figure of the woman on the far right looking at the saint, one of the most intense and best accomplished of the entire cycle, could be attributed to Francesco Albani. The Sermon is one of the most interesting scenes in the entire cycle: besides being a landmark for the young Badalocchio’s activity, it is also a work that, Úbeda writes, turns out to be of a different conception than the others, since “here space is enlarged thanks to a broad perspective surrounded by architecture that creates rigorous axes of symmetry, and the whole is not too far from some of Badalocchio’s works from around the same period, nor, as Donald Posner already pointed out, from the Raphael of the Vatican Rooms.” It is then a work that departs sharply from the outline of the master, who would never have imagined a work following Raphael so slavishly: “the most probable hypothesis,” according to Úbeda, “is that the rigorous semicircular form imposed by the architecture (not foreseen in the design) resulted in a modification of the master’s initial idea, which was replaced by a canonical model that enjoyed unquestionable prestige in Carracci’s workshop, Raphael, used because Annibale, who was ill, was unable to create a new one.”

The work ended with the works on the back wall: the two side saints, Peter and Paul, the result of a collaboration between Albani and Lanfranco, and the altarpiece with Saint Diego of Alcalá interceding for Diego Enríquez de Herrera. In the large painting, the saint, who wears the Franciscan habit as in the entire cycle, kneels imposing his right hand on Juan de Herrera’s son, acting as a go-between to obtain the grace of Christ, whom we see appear seated on a throne of clouds, surrounded by golden light, along with six angels, three on each side, looking at him with intensity. It is a difficult painting to resolve, given generically to “Annibale Carracci and workshop,” since it does not reach the quality outcomes of the works that Annibale conducted himself, but since the executors undertook to carefully imitate the style of the master, it is not given to resolve the question of the belonging of the hand that executed it.

The Herrera chapel did not disappear after the removal of the frescoes: it was in 1936, with the work on the church that followed the opening of Corso Rinascimento, where the older facade once stood, that the chapel was transformed into the entrance to the new sacristy. The cycle, however, had already been forgotten, despite the praise of critics of the time. The first to speak of it on Pietro Martire Felini in the Trattato nuovo delle cose meravigliose dell’Alma Città di Roma, a guide to the city in which the room decorated by Carracci and colleagues is described as a “beautiful chapel.” In the Lives of Giovanni Baglione, a work the Roman painter published in 1642, we read that “in the Church of S. Giacomo degli Spagnuoli for li Signori Erreri, in a chapel to S. Diego dedicated, he has worked with his exquisite colors above the altar an oil painting with a Christ in the air, and S. Diego, laying his hand on the head of a putto,” and we also find there a praise of the collaborators “who honorably by valentuomini carried themselves, and were of great honor to the master.” Again, in 1645 Giovan Pietro Bellori wrote a letter to Francesco Albani in which he called the chapel he had helped paint “divine.” Later, in 1678, in Carlo Cesare Malvasia’s Felsina pittrice we read that “un tal Signore di Erera, che fatta murar di nuovo una sontuosa cappella nella Chiesa di S. Giacomo de’ Spagnuoli, intesa la gran fama della Galleria, s’invogliò che dalla pennello dello stesso pittore venisse ella compita e adorna, offriregliene duo’ mila scudi di paoli.” Malvasia is the author who provides the most detailed description of the Herrera chapel, also illustrating in great detail the stages of work and the collaboration with Albani.

Despite its fame, the Herrera Chapel figures among Annibale Carracci’s least known and even least studied undertakings. It is not difficult to imagine why; it is mainly due to the misfortunes the work has suffered: the detachment, the removal from its location, the subsequent dispersion, the precarious state of preservation (the Barcelona fragments have been restored twice in the last 30 years), the fact that the seven Madrid fragments, since the 1970s, have never been exhibited. That is why, then, the exhibition becomes a very relevant opportunity to learn more, up close, and in its entirety, about an affair obscured by the mists of history, all the more so since it is accompanied by a thorough and useful catalog that reconstructs in detail the history of the Herrera Chapel and analyzes minutely each painting. Albeit for a limited period of time, Rome rediscovers one of its seventeenth-century treasures, and Palazzo Barberini gives the public and scholars an extraordinary opportunity for true knowledge, restoring to Annibale Carracci his last, great undertaking, and to the history of early seventeenth-century art a page that time had torn apart.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.