The Pre-Raphaelites as never seen before. What the Forli exhibition, the largest ever in Italy, looks like.

It has been almost five years since thelast exhibition in Italy dedicated to the Pre-Raphaelites: in 2019 some eighty works from London’s Tate Britain , including masterpieces such as John Everett Millais’sOphelia, John William Waterhouse’s Lady of Shalott and some of Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s sensuous female figures, such as Aurelia, Mona Vanna and Mona Pomona, arrived in Milan’s Palazzo Reale for the occasion, to recount the main themes of the British movement, a true Brotherhood that was born around 1848 following the rebellion of seven students against the Royal Academy. However, it has no comparison, no offense to the Milan exhibition, to the major exhibition project Pre-Raphaelites. Modern Renaissance now underway in Forli, at the San Domenico Museums, until June 30, 2024: more than three hundred works on display, including paintings, drawings, sculptures, tapestries, prints, photographs, works of decorative art, furniture, medals, books and jewelry, from Italian and international museums and collections, including the Royal Collection, which have been placed throughout the museum complex’s temporary exhibition spaces, including the corridors; four curators (Elizabeth Prettejohn, Peter Trippi, Cristina Acidini and Francesco Parisi) with the advice of five other experts; a direct comparison never presented with this quantity and quality with the great masters of Italian art of the past, from the 14th to the 16th centuries. It is an immense exhibition that includes the forerunners, the exponents of the three generations and the heirs of the movement, and to which one must take into account to devote (with merit) about half a day to visit it. This should not be frightening because the variety, quality and extraordinary opportunity to be able to admire so many masterpieces from numerous institutions even far away all gathered together will make the time spent there pass by without realizing it. With the satisfaction, once you leave, of having visited the largest exhibition dedicated in Italy to the Pre-Raphaelites and understanding how the old masters of Italian art strongly influenced British art from the mid-nineteenth century to the early decades of the twentieth century.

Masterpieces by the great masters of Italian art certainly stand out among the works on display, to give a few examples Cimabue’s Madonna Enthroned with Child and Two Angels , Beato Angelico’s Lamentation over the Dead Christ, Botticelli’s Pallas and the Centaur, Andrea Mantegna’s Holy Family with a Saint, Filippo Lippi’s Madonna and Child , Jacopo Palma the Elder’s Cortigiana, Giovanni Bellini’s Madonna Trivulzio, Veronese’s Judith and Holofernes , Lorenzo Lotto’s Portrait of a Crossbowman , Lorenzo Lotto’sAriadne by Guido Reni, Titian’s Risen Christ Appears to His Mother , as well as the Holy Grail tapestries produced by Morris & CO., Sidonia von Bork and the Briar Rose series by Edward Burne-Jones, Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s Roman Widow and Woman at the Window , John William Waterhouse’s Danaids , and Giulio Aristide Sartorio’s The Sage Virgins and the Foolish Virgins. But it is still difficult to make a selection of the most valuable works from the more than three hundred on display.

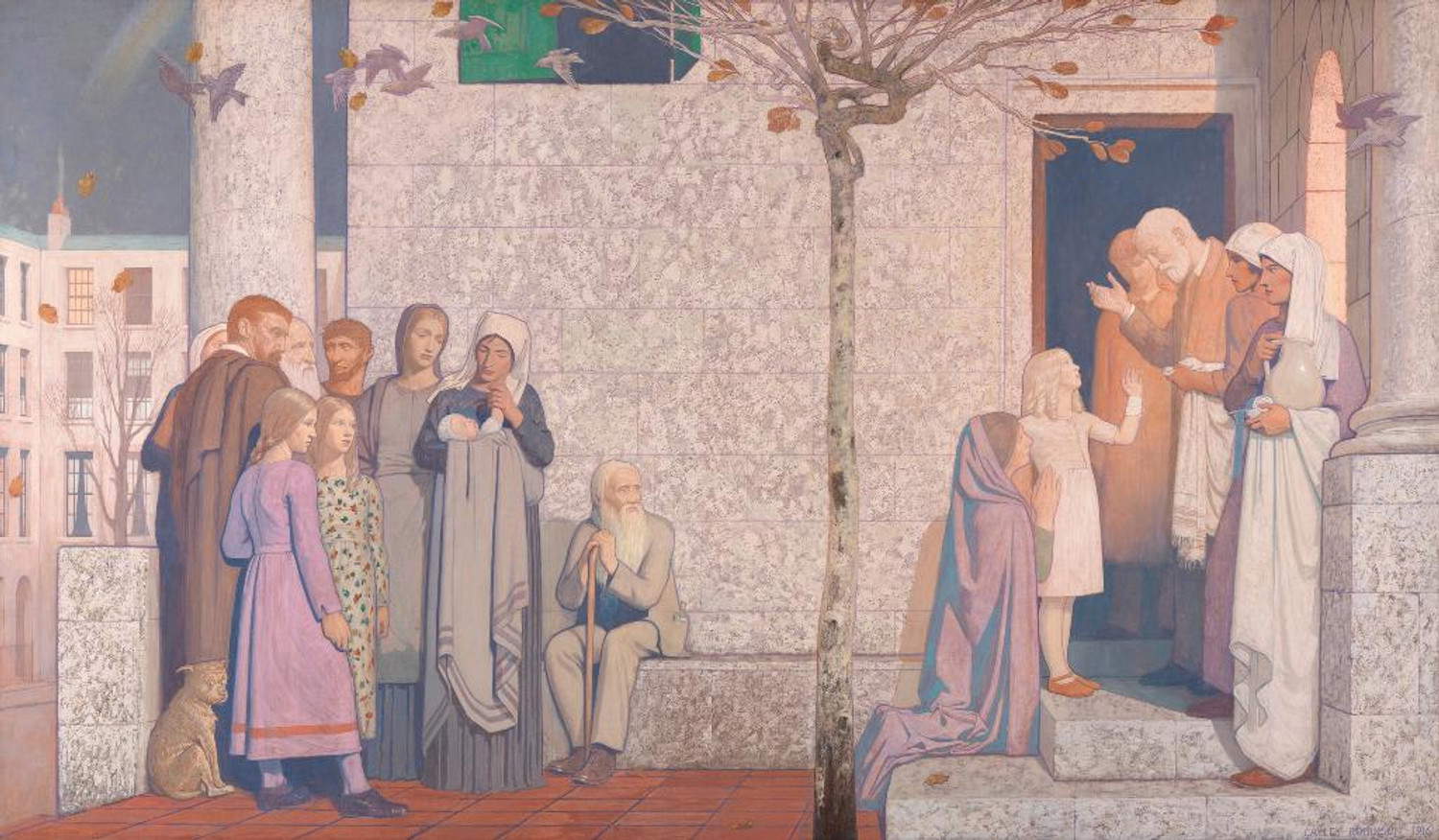

The exhibition starts as usual in the Church of St. James, where visitors are immediately confronted with one of the main intents of the major exhibition, which is to make it clear how much the Pre-Raphaelites dreamed of the art of the Old Masters, the greats of the Italian Tre and Quattrocento, especially Tuscany and among them Botticelli, and how much “the love for the Italian Renaissance,” as Elizabeth Prettejohn states in her essay, “inspired British artists to bring innovative creations to life. In the process, artists looked at Italian art of the past with fresh eyes and new insights.” It is with this in mind, a kind of statement of intent for the entire exhibition, that the initial section includes works from the Two, Three, Four Hundreds (from Cimabue to Botticelli), Nineteenth Century (Frederic Leighton) and even Twentieth Century (Frederick Cayley Robinson). Particularly significant and declarative is the color sketch for Cimabue’s celebrated Madonna is carried in procession through the streets of Florence by Leighton, within which the artist who made his debut at the Royal Academy in London in 1855 combines the triumphant procession of Florentines carrying Cimabue’s altarpiece (we now know that the Maestà is actually by Duccio and not Cimabue: it is the Madonna Rucellai now in the Uffizi) to the church of Santa Maria Novella and the visit of King Charles of Anjou, on horseback on the right. He also has Cimabue himself participate in the procession, holding the hand of his pupil Giotto surrounded by other artists such as Nicola Pisano, Buffalmacco, and Gaddo Gaddi, to celebrate Italian art, and in the far right corner of the composition he also inserts Dante Alighieri who is observing the scene with detachment(Dante and his Comedy played a very important role in thePre-Raphaelite imagination, particularly for Dante Gabriel Rossetti to whom he also owes his own name). As already mentioned, by Cimabue is Madonna Enthroned with Child and Two Angels on display here, in company with a triptych by Bernardo Daddi, an altarpiece by Taddeo di Bartolo, and then Beato Angelico, Benozzo Gozzoli, Cosimo Rosselli, Andrea della Robbia, Filippo Lippi, Andrea del Verrocchio with Lorenzo di Credi, Luca Signorelli, and Botticelli with Pallas and the Centaur ( John Ruskin, a profound connoisseur and lover of Italy, as well as a mentor and spokesman for the Pre-Raphaelite movement: He introduced his work to a geneation of students at Oxford and to a wider audience through his writings). Also presented in this first section are four monumental twentieth-century wall paintings by Frederick Cayley Robinson, who is considered a follower of Pre-Raphaelism, influenced especially by Burne-Jones; his art and style were greatly affected by his long stay in Italy, from 1898 to 1902, having the opportunity to study the techniques of tempera painting and fresco painting in the works of artists such as Giotto, Mantegna and Piero della Francesca. All four scenes divided into pairs(Orphans and The Doctor) are inspired by Renaissance frescoes, but references to Pre-Raphaelism are also found, such as Burne-Jones’s Golden Stairs in the orphans descending a spiral staircase on the left or Millais’s Spring in the woman pouring milk into a bowl. In the apse, on the other hand, are the stunning wool and silk tapestries narrating the legend of the Holy Grail designed by Burne-Jones and woven by the Morris and CO. manufactory, the result of the enduring collaboration between Burne-Jones and William Morris that culminated in the visual reworking of the greatest Arthurian legend.

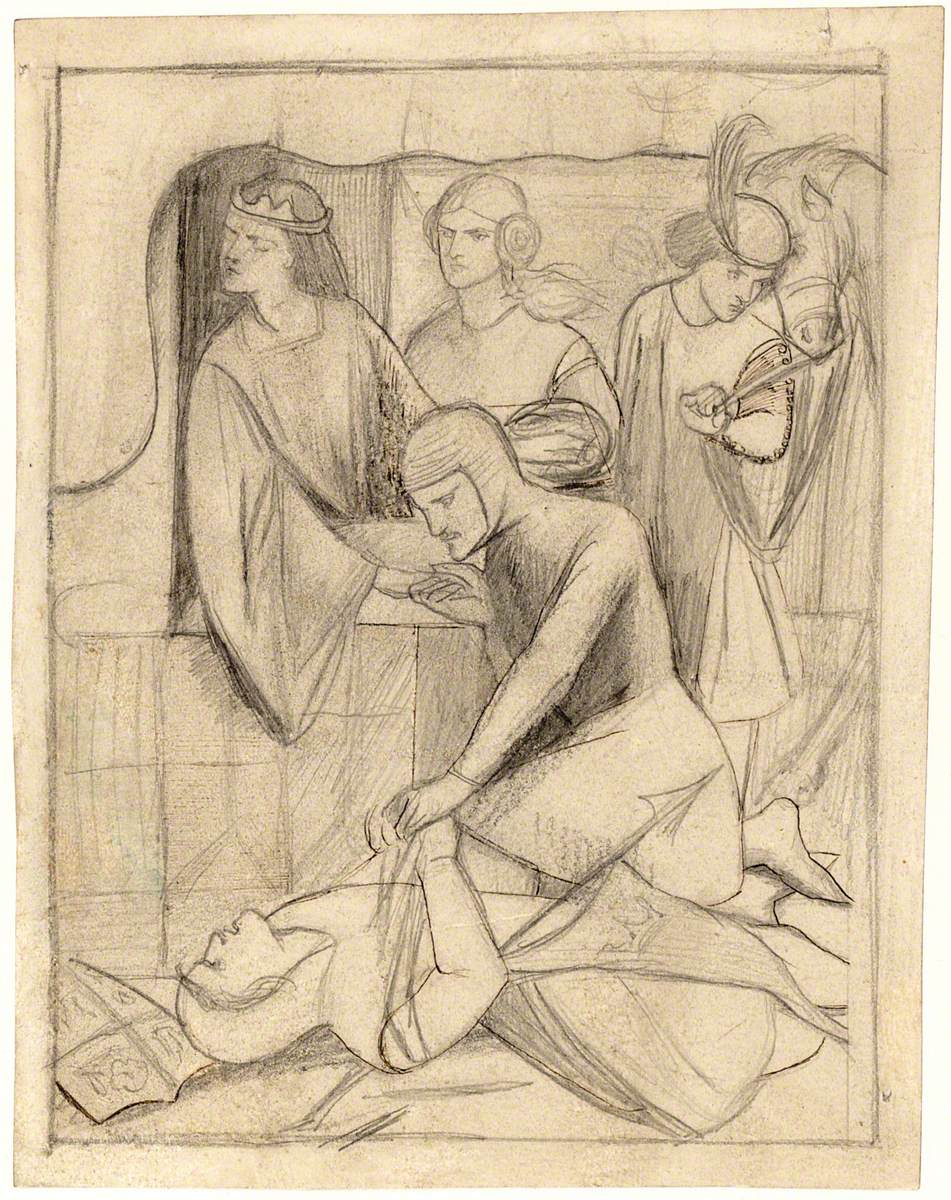

The next fifteen sections of the exhibition then unfold from here, inside the convent, starting with the influence of the artists considered to be the forerunners of the Pre-Raphaelites, namely the Nazarenes, German-speaking painters from the Academy of Vienna who were active in Rome and proposed to imitate Raphael’s predecessors, thus looking back to a “primitive” past and characterized by the use of glossy colors, a glossy rendering of the surface, natural references and the study of details, on two artists in particular: William Dyce and John Rogers Herbert. On display are several paintings by both of them in which there is a remarkable connection to the Italian art of the Old Masters: Examples are William Dyce’s Lamentation over the Dead Christ, Virgin and Child (his is also the painting that depicts Titian as a child contemplating a statue depicting the Madonna surrounded by plants and flowers from which he will draw a variety of natural colors), while in John Rogers Herbert’s King Lear and Cordelia, a painting of the fresco that the artist created for the new Palace of Westminster, the Nazarene influence is notable in the monumentality of the king, whose pose is reminiscent of the Sistine Sibyls, in the pictorial patina and in the precision of the drawing. After a section devoted to the so-called Gothic Revival , which characterized the entireVictorian era, the period of Queen Victoria ’s long reign (depicted here in the exhibition with Prince Albert in a painting by Edwin Landseer) during which the the Pre-Raphaelite movement, and a section paying homage to the aforementioned John Ruskin with his drawings and watercolors of architecture, monuments, and works that he himself had occasion to see in Italy, we move on to the small focus sections presenting the birth of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood and its early protagonists: Ford Madox Brown, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, John Everett Millais, and William Holman Hunt. The Brotherhood was founded in 1848 by seven students of the Royal Academy who, dissatisfied with the overly academic teaching given by the institution, got together to talk about and delve into the art of the Old Masters of Italian art, namely those who preceded Raphael, whose excessive virtuosity, misplaced pomposity of the characters depicted and lack of adherence to the truth of nature, traits that the Urbino had brought together in an exemplary way in his Transfiguration. Pre-Raphaelite painting thus sought to respond to the need to return to the old honesty, that is, to so-called primitivism. It was to Ford Madox Brown’s credit that the Pre-Raphaelites knew and were influenced by the imprint of the painting of the aforementioned Nazarenes, while the interest in primitive culture condensed around the engravings of the medieval frescoes of the Camposanto in Pisa published by Carlo Lasinio in 1812. On the other hand, the idea of creating a true Confraternity was due to Rossetti, the son of an exiled Italian Carbonaro, and also the founding of the magazine The Germ, which made explicit the literary aspect of the movement. Of the early protagonists, drawings and paintings are on display here, such as Rossetti’s Paolo and Francesca and Dante in Meditation, which are also flanked by drawings by Elisabeth Siddal, his muse and wife as well as artist and poetess, Millais’ Lorenzo and Isabella, and Hunt’s Claudio and Isabella, to name a few. It continues with painters such as Walter Howell Deverell, Charles Allston Collins, Joseph Noel Paton who adhered to the Pre-Raphaelite cultural climate and form even if not directly involved in the Brotherhood.

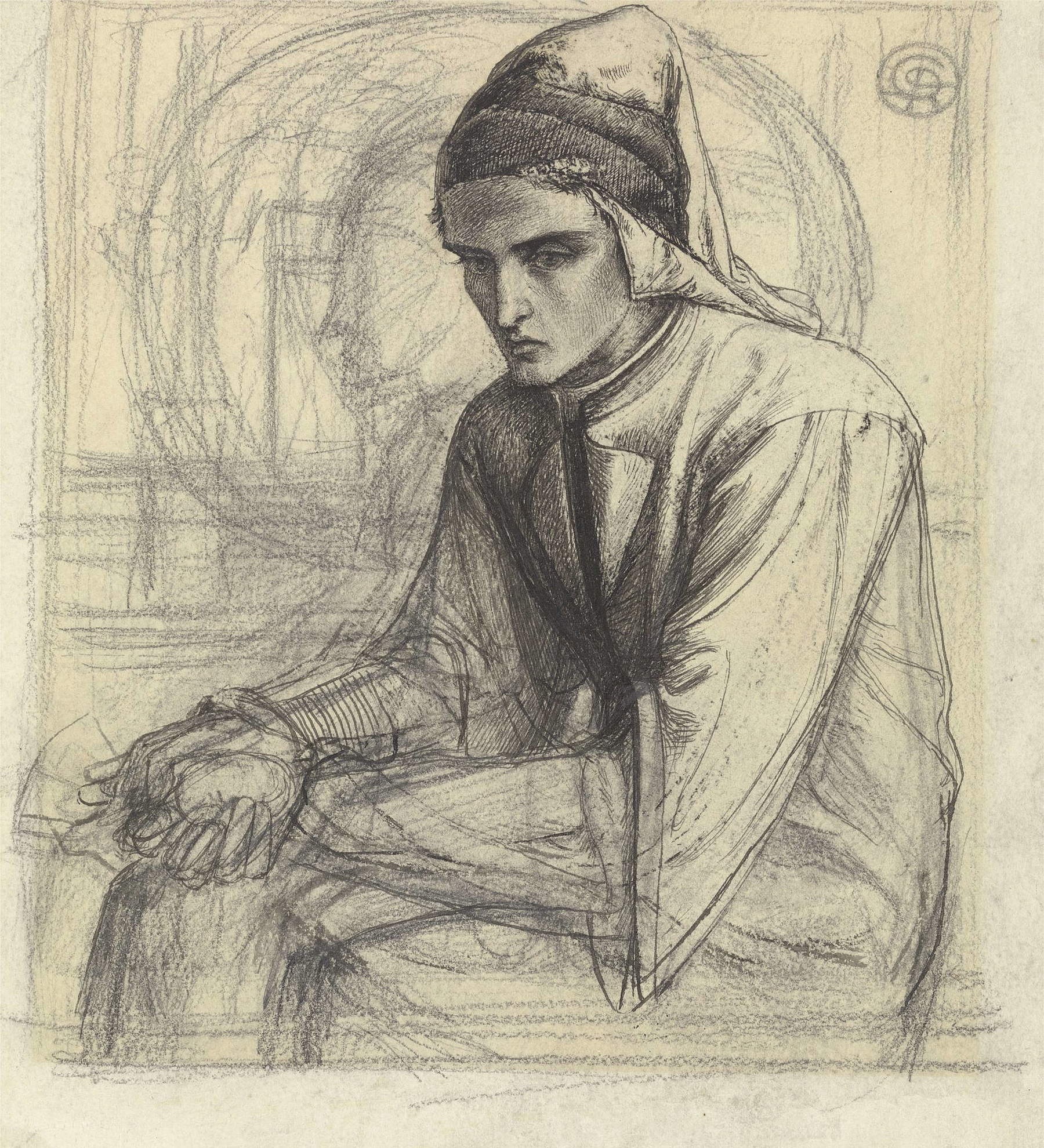

We then come to the Hall of Frescos, entirely devoted to Edward Burne-Jones and his connection with Italy. The artist first traveled to the Bel Paese in 1859 in the company of his painter friend Valentine Cameron Prinsep, and here he had the opportunity to see a lot of Italian art, especially in Florence, with forays into Venetian art as well, but he then returned to Italy several more times, including with Ruskin. He was fascinated by Botticelli, Mantegna, and Michelangelo. Of the latter, during one of his trips to Italy, he had occasion to admire the frescoes in the Sistine Chapel, which he studied by making very faithful copies. It is for this reason that in this room, in addition to Burne-Jones’s masterpieces, there are also drawings by Michelangelo himself and Pontormo, Andrea Mantegna ’s Holy Family with a Saint from the Museum of Castelvecchio, and works by Filippino Lippi, Cosimo Rosselli, and Giovanni Bellini. Prominent among the British artist’s masterpieces are Sidonia von Bork for whose dress Burne-Jones was inspired by Giulio Romano ’s Portrait of Margaret Palaeologus preserved at the Royal Collection Trust in London, The Temple of Love and The Fall of Lucifer, Lancelot at the Chapel of the Holy Grail, which recalls one of the scenes from the Holy Grail tapestries on display in the first section of the exhibition, The Baleful Head, Love among the ruins , which as Elizabeth Prettejohn writes in her essay is a summation of the influences Burne-Jones picked up during his encounters with the Italian Renaissance (from the deep blue cloak of Renaissance Madonnas, the architecture of Mantegna, Crivelli or Piero della Francesca, the frieze with playful putti that calls to mind Donatello). And especially the Briar Rose series from the Museo de Arte de Ponce inspired by the fairy tale of Sleeping Beauty. Leaving the hall of frescoes, one notices the beautiful floor painted by Burne-Jones commissioned by his friend Wlliam Graham as a birthday present for his daughter, and one walks down the entire corridor in the direction of the monumental staircase leading to the upper floor: the corridor is devoted to the applied arts related to the London firm Morris & CO, which started in 1861 with the intention of reforming the applied arts by integrating them with the “ornamental quality which men adopt to add to utilitarian objects,” that is, to bridge that divide between pure and applied arts. Thus chairs, vases, cups, textiles, plates, and tiles related to the manufacturing firm are displayed here.

The upper floor starts again with a section devoted to the fascination with Botticelli, whose painting was rediscovered inVictorian England thanks to John Ruskin, who called him the greatest painter among the Florentines, but also thanks to exhibitions, acquisitions in Italy by London museums, and several artists in the Victorian age were inspired by Botticelli’s painting. Examples are, as can be seen in this section that also counts the Madonna and Child from the Stibbert Museum, Simeon Solomon with his Love in Autumn, a work probably painted during a stay of the artist in Florence in 1866 made to study the works of Renaissance artists and in which the mystical and idealizing vision of his art is clear, or Walter Crane with Diana and Endymion that refers to Botticelli particularly in the draperies. Remarkably significant, however, for this Botticelli-mania are the works exhibited here by Evelyn De Morgan (present with a study from the Birth of Venus) and Christiana Jane Herringham (present with Head of Mary Magdalene taken from the Uffizi’s St. Ambrose Altarpiece ): the two painters copied and studied many works by the Florentine painter, thus contributing significantly to the rediscovery of the Italian artist and to the dissemination of Botticelli’s characteristic features.

Edward Burne-Jones,

Edward Burne-Jones,

It continues with a section devoted to the female figures depicted by Dante Gabriel Rossetti, through whom he experiments, as in Louisa Ruth Herbert, the lesson on the study of Venetian painters, or explores the expressive possibilities in a game of literary assonances, as in Bocca baciata, referring to a novella from Boccaccio’s Decameron , thus making explicit his two great passions, namely painting and literature; the women depicted by Rossetti are also a concentration of sensuality, like his Roman Widow, as sensual were the women depicted by Italian masters of the past such as Palma il Vecchio. painter of Venetian scope. His friendship with Jane Morris, here portrayed by Rossetti himself, later became a source of inspiration for late works such as The Woman in the Window, taken from Dante’s Vita Nuova, but which also possesses autobiographical significance: Jane looks pityingly at the painter distraught over the death of Elizabeth Siddal just as Dante’s woman turned her consoling gaze to Dante after the death of Beatrice.

This is followed by two sections devoted to Frederic Leighton and George Frederic Watts: on the strength of his training in continental Europe and his knowledge of Italian art, the former played an important role in spreading Italian culture in Britain (his works are here compared with Guido Reni, Lorenzo Lotto, and Veronese); his special fascination with Michelangelo is evident in Michael Angelo nursing his dying servant and Jonathan’s token to David. The latter had the opportunity to spend four formative years in Italy, where he was fascinated not only by Michelangelo and Raphael, but especially by the painters of 16th-century Venice, above all Titian (the Resurrected Christ Appears to the Mother is shown here) and Veronese.

It goes on next to present the artists who exhibited at the Grosvenor Gallery, founded in 1877 in London as an alternative to the Royal Academy; the gallery became a fashionable place frequented by the aristocracy and upper middle class, where works were placed individually to facilitate their contemplation, and an exhibition venue that encouraged the presence of the women artists who exhibited there regularly: among them was Evelyn De Morgan, a painter recently reevaluated among the women of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, who drew clearly recognizable motifs from Botticelli, as in Flora , and who imbued some of her works with the spiritualism of which the artist was a devotee.

We draw to a close with the last generation of the Pre-Raphaelites, what some critics of the time referred to as the Neo-Pre-Raphaelites, since they retained a passion for Italian Renaissance painting, which they adopted as a source of inspiration for refounding 20th-century modern art on the principles of tradition. Among the names of this third generation are Charles Ricketts, Charles Shannon, Thomas Cooper Gotch, and John William Waterhouse. Finally, the exhibition concludes with works by Giovanni Costa, Lemmo Rossi-Scotti, Filadelfo Simi, Giulio Bargellini, Giulio Aristide Sartorio, and Adolfo De Carolis, painters who felt at the end of the 19th century a certain interest in Pre-Raphaelite painting and who, on the model of what happened in England, formed or approached the society In Arte Libertas, a group born around the idea of a renewal of art. Fundamental to the relationships and exchanges with the Pre-Raphaelite milieu, as Francesco Parisi explains in his catalog essay, was Giovanni Costa, who undertook several trips to England, thus establishing relationships with the London art milieu and in particular with Frederic Leighton. In turn, Costa played a liaison role with Italian artists who were beginning to look at the lessons of the past through the metre across the Channel. Giuseppe Cellini, featured in the exhibition with Fantasia, presented at the annual review of the Società degli Amatori e Cultori di Belle Arti in Rome, played a major role within In Arte Libertas, modeling it on thatut pictura poësis already widely professed in the Pre-Raphaelite area. Giulio Aristide Sartorio, who was not among the founding members of the society, soon became its secretary, however, holding to precise authorship of the idea of forming a group marked by rebellion against the models of official and academic art and against a prissy style that had imposed itself in Rome with Mariano Fortuny. It was Count Giuseppe Primoli who commissioned him to paint The Sage Virgins and the Foolish Virgins, a masterpiece that can be admired in the exhibition, with which he encouraged him to delve into Pre-Raphaelite culture: the choice of the triptych on panel and the carved Gothic frame are elements that refer to the primitive tradition of the Italian Tre Tre and Quattrocento, but the female figures and the atmosphere depicted clearly recall the Pre-Raphaelite style. At the end of the century Adolfo De Carolis, who joined the association in 1896, renewed the movement’s interest in aPre-Raphaelite aesthetic: examples of this are his Castalidi, also exhibited here, interpreted as a symbol of the transfiguring capacity of art and the eternal renewal of poetic inspiration. It therefore concludes with these artists who brought further renewal to Italian art by drawing on the Pre-Raphaelite model the great Forlì exhibition on the British movement that originated in the Victorian age and came to influence even the early twentieth century.

The catalog that accompanies the exhibition is also presented as a large volume that collects all the works on display, complete with cards, and illustrates with a dozen essays by the curators and experts all aspects of Pre-Raphaelism, from its birth to its themes, to its links with Italy and the graphic arts. An exhibition, therefore, that will surely be considered a milestone in the dissemination of knowledge of the entire Pre-Raphaelite movement in subsequent years as well.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.