By a fortuitous coincidence, the rich exhibition Le Signore dell’arte, the show with which Palazzo Reale in Milan composes a fragrant anthology of women’s painting between the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, falls exactly fifty years after the publication of an essay without which perhaps this exhibition would never have come into being: the publication of Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists? the study with which Linda Nochlin effectively initiated modern historical research on women in art, and which would lead, five years later, to the exhibition Women Artists: 1550-1950, the first wide-ranging survey of the subject, capable of traversing four centuries of history through the work of eighty-three women. The Los Angeles County Museum of Art exhibition had achieved at least two key results: first, it cleared the field of misunderstandings and prejudices about women in art history, loudly affirming that, though obscured and almost hidden, that presence has always been alive. Second, it opened up a fruitful season of scholarship that helped to illuminate with substance the real bearing of women in art history, through books and numerous exhibitions capable of descending from the general of the California review to the particular of the many monographic focuses or on individual periods. Just to narrow our gaze to Italy, we cannot fail to mention the works of Consuelo Lollobrigida or Vera Fortunati, and the many exhibitions that have analyzed the personalities of individual artists (among the latest, Giovanna Garzoni at Palazzo Pitti in 2020, Plautilla Nelli at the Uffizi in 2017, Artemisia Gentileschi at the Museum of Rome in 2016, and before that, the Roman monographic in 2001) or groups of women artists(Di mano donnesca, curated by Consuelo Lollobrigida at Palazzo Venezia in 2012, and then L’arte delle donne dal Rinascimento al Surrealismo also at Palazzo Reale in 2007, curated by Beatrice Buscaroli, Hans Albert Peters and Vittorio Sgarbi).

The field of investigation, therefore, is vast, and the curators of the Milan exhibition(Annamaria Bava, Gioia Mori and Alain Tapié) have chosen to focus on a precise period, that in which relevant transformations occurred throughout Europe (although the gaze of the exhibition focuses exclusively on Italy) that would lead to a progressive emancipation of the woman artist to the point of bringing her during the seventeenth century, to be able to undertake a completely independent career (the most relevant cases are those of Giovanna Garzoni and Artemisia Gentileschi, with whom the Milanese exhibition closes). There were numerous obstacles that prevented women from becoming independent artists. Meanwhile, the educational system in force until the late 16th century, which for women’s education provided religious precepts, notions of reading, writing and calculation, and activities considered typically feminine, such as sewing and weaving: there was no room for anything else. Then, there were practical reasons: for example, the impossibility of studying the male body from life, an activity that women at the time were forbidden to do (the only way they could practice anatomy was to copy from statuary or prints). No less onerous were the duties associated with marriage and motherhood.

These are themes that are barely touched upon in the exhibition: the curators’ stated idea is not to linger on issues that pertain more to sociology or anthropology (but also to the history of art criticism, since the image of women in artistic literature is not touched upon) than to historiography, nor to take a rigidly scientific slant and focus on art-historical topics, avoiding tying the exhibits entirely to historical or social analyses. The poles are thus the aforementioned 1976 Los Angeles exhibition on the one hand and, on the other, the exhibition The Other Half of the Avant-Garde curated by Lea Vergine in 1980 still at the Royal Palace: the aim of Le Signore dell’arte is therefore to propose a middle way, a collection of histories of women sculptors and painters in which the biographical data is proposed to the public only if possibly necessary to illustrate the works, and provided with a frame (or a “grid of investigation,” as Gioia Mori defines it in the catalog) taken from Giorgio Vasari’s Lives. A framework that effectively helps an audience far removed from the topics discussed to understand the three ways in which, between the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, a woman could have access to the profession of artist: either because she was herself the daughter of an artist, or because she practiced as a nun in a convent, or because she enjoyed the privileged status of a noblewoman that relieved her of certain duties that fell instead to women of lower social status and allowed her to be able to pursue a formal education in painting. The advantage of such an approach is that it avoids risky readings or myths, while its limitation is that it cannot provide the public with elements of social history that would be important for a better understanding of the complex phenomenon of women’s art between the 16th and 17th centuries, with the result that one risks leaving the exhibition with the perception of having witnessed a long overview (which is not without some oversights: in such a wide-ranging exhibition the absence of a Diana De Rosa, for example, is surprising) without a solid glue.

|

| Exhibition Hall |

|

| Exhibition Hall |

|

| Exhibition Hall |

The beginning, however, is sparkling, with a prologue entrusted to Sofonisba Anguissola ’s Madonna dell’Itria (Cremona, 1532/1535 circa Palermo, 1625): it is one of the most recent acquisitions in the Cremonese painter’s catalog (it was recognized as such in the early 2000s), is an indispensable reference point for the reconstruction of the artist’s Sicilian activity, and was restored for the Palazzo Reale exhibition. The work, whose name refers to the iconographic type of the Madonna Odigitria, tells of a legend according to which, at the time of iconoclasm, some monks allegedly hid an image of the Odigitria in a crate by entrusting it to the waves of the sea, thus causing the work to reach Italy. The panel, which for the first time leaves the church of the former monastery of the Santissima Annunziata in Paternò, was re-analyzed precisely in preparation for the exhibition: the studies have confirmed the attribution and also identified some autobiographical elements in the altarpiece (for example, the face of the Virgin in which a self-portrait of Sofonisba has been identified, and some details in the background that refer to the vicissitudes of the artist’s first husband, the Sicilian nobleman Fabrizio Moncada, who, moreover, probably, also participated in the execution of the painting, as revealed by the deed of donation to the church of San Francesco di Paternò and as some rather uncertain portions let slip), as well as emphasizing the complexity of the spatial layout of the altarpiece, revealing the talent of a cultured artist, capable of doing “very rare and beautiful things in painting,” as Vasari had occasion to write. In the next room, opened by the Coat of Arms of the Fat family, a rare masterpiece by Properzia de’ Rossi (Bologna, c. 1490 - 1530), the first sculptress known to us and the only woman to whom Vasari dedicated one of his Lives, Sofonisba Anguissola’s activity is summarized through several portraits (the one of the Lateran canon on loan from the Pinacoteca Tosio Martinengo in Brescia is of extraordinary quality) that culminate in the Chess Game coming from Poznań, a work that also reveals the relations between the painter and Vasari, who in the Lives relates that he saw in his father’s house “a picture made with much diligence, portraying three of his sisters in the act of playing chess, and with it them an old woman of the house, with such diligence and readiness, that they seem alive, and that they lack nothing but speech.”

The Polish canvas plays a relevant role in the exhibition since, along with the Madonna dell’Itria, it helps to dispel the prejudice that Sofonisba Anguissola was primarily a portrait painter, however, at the time a painter could only specialize in certain genres including the miniature, simple religious painting intended for private devotion, still life or, indeed, portraiture: it has been said of how women were precluded from receiving a complete artistic education, and to this it would be necessary to add the fact that it was much more difficult for a woman to travel to study and observe other models (Sofonisba, for her part, succeeded, since she moved often to follow her husbands’ activities). For these reasons women only tried their hand at genres considered minor-these are aspects that are barely touched upon in the exhibition. In such an articulated exhibition, long lunges into individual figures are also difficult: there is no way, therefore, to delve into the broad humanistic culture that animated Sofonisba Anguissola’s work, nor her many stylistic references. However, her role as mentor to her sister Lucia (Cremona, 1537/1542 circa Cremona, 1565), also a painter like her fifth sister Europa (Cremona, 1548/1549 Cremona, 1578), who are represented in the exhibition by one work each, is adequately emphasized. The section on noblewomen painters concludes with the presence of two outstanding pieces, the Mystic Marriage of St. Catherine by Lucrezia Quistelli (Florence, 1541 Florence?, 1594), a talented pupil of Alessandro Allori (the work reflects the modes of Florentine painting of the second half of the 16th century) who was able to paint all her life having married a man, Clemente Pietra, who was a convinced advocate of a more active role for women in the intellectual life of the society of the time, and the Portrait of Faustina del Bu falo by Claudia del Bufalo (active in Rome between the end of the 16th century and the beginning of the 17th), the only known work by an artist still to be explored in depth.

|

| Sofonisba Anguissola, Madonna dellItria (1578-1579; oil on panel, 239.5 x 170 cm; Paternò, parish Santa Maria dellAlto, church of the former monastery of Santissima Annunziata) |

|

| Sofonisba Anguissola, Chess Game (1555; oil on canvas, 70 x 94 cm; Poznań, Fundacja im. Raczyńskich przy Muzeum Narodowym w Poznaniu, MNP FR 434) |

|

| Lucrezia Quistelli, Mystic Marriage of St. Catherine (1576; oil on canvas, 180 x 120 cm; Silvano Pietra, parish church of St. Mary and St. Peter) |

The section on women artists in the convent cannot do without the first of this group, the Florentine Plautilla Nelli (Florence, 1524 Florence, 1588), present with a Saint Catherine of Siena that is part of an almost serial production, well investigated by the exhibition that the Uffizi dedicated to the artist three years ago. Undisputed protagonist of this part of the exhibition, however, is Orsola Maddalena Caccia, née Teodora (Moncalvo, 1596 1676), daughter of the Guglielmo Caccia who was among the most important Piedmontese painters of the period: the nun was instructed by her father to whom she collaborated throughout her career, often substituting for him in certain commissions. “Heir to the Caccian tradition,” Antonella Chiodo writes in the catalog, “her painting ranged from altarpieces (which qualify her as one of the most prolific artists of the modern age) to chamber paintings, to a precious, as much as minute, production of silent still lifes.” Thus we range from a youthful Saint Cecilia playing an organ, a brilliant canvas that also suggests to the relative the Caccia family’s vast musical culture, to an admirable Nativity of Saint John the Baptist that is both intimate and magniloquent, to the more mature (but perhaps less glib) outcomes of the Sibyls series. Also on display by Orsola Caccia are two recent discoveries, namely theAllegoria mistica and Santa Margherita d’Antiochia from the sanctuary of Le Grazie in Curtatone, found in a storage room of the sacred building in 2011 by Paolo Bertelli and Paola Artoni: the discovery has strengthened hypotheses about the links between Orsola Maddalena Caccia and the Mantuan lands, and the Milan exhibition is an opportunity to learn more about the two works. With the singular case of Lucrina Fetti (Rome, 1595 circa Mantua, 1651), sister of the famous painter Domenico, who was a dedicated nun for the Mantuan court (witness the Portrait of Eleonora Gonzaga I), this part of the exhibition closes.

Thus we enter the most substantial section, the one devoted to the daughters of art, the women painters who trained in their father’s workshops, often, however, freeing themselves from their parent’s ways. Such was the case for Lavinia Fontana (Bologna, 1552 Rome, 1614), Prospero’s daughter, a painter who was able to achieve fame and success and to carry out, according to Gioia Mori, a revolution that was both professional and private, in that she was “proud of her status as a cultivated and erudite woman” to the point of exhibiting it in some portraits (the one at the spinet, for example, coming from the Accademia Nazionale di San Luca) and choosing as her companion a man who allowed her to work: “she did not therefore live in the shadow of a man,” writes the curator, “if anything, she overshadowed a man: ananomaly for the times, which, however, did not disrupt the legal power of her husband, signer and guarantor in contracts for his wife.” Lavinia’s revolution, however, is also to be sought in the constant evolution of her language, in the breadth of the themes she tackled, and in the complexity, as much symbolic as formal, of the paintings she delivered to patrons. Her versatility is demonstrated in the Palazzo Reale exhibition by two paintings that stand at the antipodes between them: the large Gnetti Altarpiece, once in the Church of the Servi in Bologna and then arriving in Marseille after a series of passages in private collections, exemplifying the leading role in the sphere of Counter-Reformation painting that Lavinia had, and a delightful Galatea riding the waves of the storm on a sea monster, which belongs instead to a “secret” production, made up of mythological subjects often painted with sharp erotic accents, and which has become the subject of specific investigations only recently. In between are portraits, biblical and religious subjects, including even a St. Francis from the Archbishop’s Seminary in which Lavinia nonetheless reveals a marked sensitivity to the landscape theme.

Lavinia is counterbalanced by the delicate painting of Barbara Longhi (Ravenna, 1552 Ravenna, 1638), an artist who, unlike her Bolognese peer, though very promising was unable to detach herself from her father’s ways, although she was able to interpret them in a more intimate and gentle manner, as her works on display attest, including the important Saint Catherine of Alexandria from the Pinacoteca Nazionale in Bologna, in which many have wished to see a self-portrait of the painter. It continues in the Bologna reniana, first with Ginevra Cantofoli (Bologna, 1618 1672), another recent discovery that enchants the public with a Young Girl in Oriental Dress that was first ascribed to her in 2006 by Massimo Pulini (and since then the work has become part of the albeit restricted catalog of an artist on whom it is assumed that studies will continue apace) and then with another true exhibition within the exhibition, a long corridor dedicated to Elisabetta Sirani (Bologna, 1638 1665), an extraordinary artist who would have been capable of who knows what other marvels if an untimely death had not seized her at the age of only twenty-seven.

“Heroine painter,” Carlo Cesare Malvasia called her: and indeed, Elisabetta had uncommon gifts that surprised her contemporaries: she was trained in the workshop of her father Giovanni Andrea Sirani, of which Elisabetta took over at a very young age, in 1662, following an illness that struck Giovanni Andrea and prevented him from continuing to paint, and she contributed to the spread in Emilia of the Reni manner, of which she was an original and sensitive interpreter, as the paintings on display show, from the religious (the Holy Family, St. Anne, St. John and an Angel from the Borgogna Museum in Vercelli) to the historical ( Portia Wounding Herself at the Coscia, which, writes Adelina Modesti, “depicts a person with great strength of will who inflicts a cruel wound in order to show courage and determination and convince her husband that even a woman can be stoic, thus prompting him to share his political choices with her,” and in doing so Elisabetta presents Portia as “a politicized heroine with masculine traits”) to mythological subjects such as the famous Galatea from Modena and Circe from a private collection. These two paintings are extremely significant, because they both testify to the great freedom of invention of a painter who often departed from the groove of traditional iconographies to advance personal interpretations (Galatea is a delicate little girl who lets herself be carried away by the waves, Circe is not the sorceress who ensnares Ulysses and his companions, but is a queen endowed with vast knowledge), and because they are among the most interesting proofs of the vigor of Elisabetta’s drawing. The dialogue with Ginevra Cantofoli, who was Elisabetta’s pupil, recalls the theme of the “professionalization of women’s artistic practice” (so Modesti had written in 2001) that was the Emilian painter’s main achievement: in fact, Elisabetta Sirani animated a sort of informal, all-female private academy in which young female artists were initiated into the practice of their craft. For the first time in history, therefore, the model of the male teacher was being departed from, since women, until then, had learned to paint from a male figure: in the exhibition, however, this achievement is not sufficiently emphasized.

|

| Orsola Maddalena Caccia, Santa Margherita dAntiochia (ca. 1640-1650; oil on canvas, 95 x 73 cm; Curtatone, sanctuary of the Beata Vergine delle Grazie) |

|

| Orsola Maddalena Caccia, Sibilla persica (c. 1640-1650; oil on canvas, 110 x 78.5 cm; Asti, Fondazione Cassa di Risparmio di Asti collection) |

|

| Lavinia Fontana, Galatea and Cupids Ride Storm Waves on a Sea Monster (c. 1590; oil on copper, 48 x 36.5 cm; Private Collection) |

|

| Lavinia Fontana, Saint Francis Receives the Stigmata (1579; oil on canvas, 63 x 75 cm; Bologna, Archiepiscopal Seminary, F7Z0068 - F7Z0069) |

|

| Barbara Longhi, Saint Catherine of Alexandria (c. 1580; oil on canvas, 70 x 53.5 cm; Bologna, Pinacoteca Nazionale, inv. 1097) |

|

| Ginevra Cantofoli, Young Woman in Oriental Dress (second half of the 17th century; oil on canvas, 65 x 50 cm; Padua, Museo darte Medioevale e moderna, legate del Conte Leonardo Emo Capodilista, 186) |

|

| Elisabetta Sirani, Galatea (1664; oil on canvas, 43 x 58.5 cm; Modena, Museo Civico dArte) |

|

| Elisabetta Sirani, Portia injuring herself in the thigh (1664; oil on canvas, 101 x 138 cm; Bologna, Collezione dArte e di Storia della Fondazione Cassa di Risparmio in Bologna, inv. M32228) |

A figure on whom studies will have to continue is the mythical Tintoretta, or Marietta Robusti (Venice, 1554 ca. 1590), Tintoretto’s daughter, about whom we know very little: the exhibition features an uncertain self-portrait from the Galleria Borghese, on which more light will have to be shed, and the UffiziSelf-Portrait assigned to Marietta’s hand as early as 1675, and the only existing work that can be traced back to her hand without doubt. In the same room we touch on the figures of Chiara Varotari (Padua, 1584 Venice, post 1663), sister of the more famous Padovanino, of whom two portraits are exhibited; Maddalena Natali (Cremona, 1654 Cremona or Rome, documented until 1675), present with a Portrait of a Prelate; and above all Fede Galizia (Milan? 1574/1578 Milan, after June 21, 1630), to whom this year the Castello del Buonconsiglio in Trento is dedicating its first monographic exhibition, so much so that some of the works in the Palazzo Reale had to leave the exhibition prematurely, replaced by reproductions, to move to Trentino. The Milan exhibition, however, did not fail to document much of Faith’s activity, until recently unjustly known primarily as a naturamortista: the Galleria Borghese’s Judith is one of the symbols of the show, and the San Carlo of Milan Cathedral demonstrates her skills as a painter of interesting altarpieces.

The overview of the “daughters of art” continues with another hapax, the only documented work by Rosalia Novelli (Palermo, 1628 Palermo, documented until 1689), daughter of Pietro who was the leading Sicilian painter of the 17th century: it is an Immaculate Madonna and St. Francis Borgia from the Church of Jesus of Casa Professa in Palermo, placed in fruitful dialogue with a larger Sposalizio della Vergine by Pietro. The work, dated 1663, was commissioned from the young woman by the Jesuits of Palermo probably because of the latter’s relationship with her father, given the choice, unusual for Sicily at the time, of entrusting an altarpiece to a woman: the Palermo canvas, writes Santina Grasso, is “almost a collage of cues taken from her father’s works: from the diagonal spatial construction of the Lanfranchian type, much used by Novelli, to the warm chromatic and luministic agreements of Vandyckian origin, to the indistinct lightness of the background.” Even the figure of the Virgin is almost copied from one of her father’sImmaculata. Rosalia was not, however, a mere imitator of Peter: the works that have been attributed to her on the basis of stylistic similarities denote an ability to move toward more personal pursuits, as attested, again in the exhibition, by a drawing with a Santa Prassede recently attributed to the Sicilian artist. If, therefore, his father’s drawings appear more rapid and synthetic, this sheet denotes a high attention to detail and the search for definition: the signature of Rosalia appearing on the drawing is therefore to be read not as an attestation of the ownership of a drawing by his father (this is how it had been read in the past), but as proof of its execution. The scarce presence of drawings is, moreover, one of the exhibition’s weak points: Elisabetta Sirani, for example, was a formidable and very talented draughtsman, but this dimension of hers in the exhibition is not even mentioned.

If the figure of Rosalia Novelli has still been little explored (a systematic survey of her has been initiated in recent years by the aforementioned Grasso), the outlines of Margherita Volò (Milan, 1648 1710), also known as Margherita Caffi from the surname of her husband Ludovico, appear more consolidated. She was an autonomous artist capable of launching a brilliant career as a florist: some of her still lifes from private collections, placed in comparison with two Vasi (vases ) by her father Vincenzo Volò, are glaring examples of the virtuosity of which Margherita was capable, specializing in floral compositions: her sisters Francesca and Giovanna, also artists, also florists and also present in the exhibition, did not fail instead to include figures in their paintings.

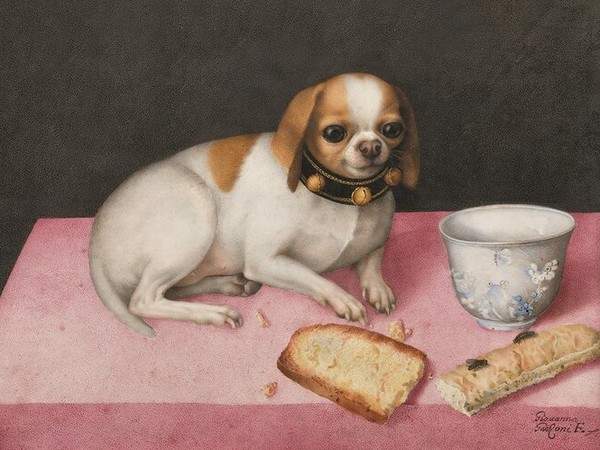

Then it was the turn of the “academics,” or the women painters who managed to be admitted to the artists’ associations, all gathered in one room: the first to have succeeded in the feat was Diana Scultori (Mantua, 1547 circa Rome, 1612), the daughter of a Veronese sculptor, as her surname suggests. She devoted herself to the art ofengraving, looking especially to Giulio Romano (e.g., the Jesus Christ and Ladultera, one of her best proofs, derives from an invention by Raphael’s great pupil), got to know Vasari, and set up a successful business. Success also accrued to Giovanna Garzoni (Ascoli Piceno, 1600 Rome, 1670), the best-known of the artists in the room, an academician of St. Luke’s, distinguished in particular for her magnificent miniatures, the author of realistic still lifes on parchment that, Tapié writes, “challenge reality with their conceptual truth, surpassing nature thanks to the refinement of illusionistic play,” and clothed botanical painting with new meanings, lifting it from its purely decorative or scientific role. In the exhibition, therefore, one appreciates his lenticular gaze, as much on plants as on animals (see Quince and Lizard), his meticulous rendering of detail that reaches its zenith in the celebrated Canine with Biscuits and a Chinese Cup, but also his skill as a portrait painter that can be observed in the portraits of Emanuele Filiberto and Carlo Emanuele I of Savoy in the Royal Museums of Turin, which on the occasion of the exhibition were the subject of an in-depth campaign of diagnostic investigations, which Annamaria Bava gives a full account of in an essay in the catalog. Part of the room is devoted to the touching story of Virginia Vezzi (Velletri, 1600 Paris, 1638), who frequented Simon Vouet’s workshop to the point of falling in love with him and marrying him: the two became a couple in life and work, since they formed an association that ended only with her untimely death. The exhibition displays anAngel with a Tunic and Dice that is the result of their collaboration.

|

| Marietta Robusti known as Tintoretta, Self-Portrait with Madrigal (c. 1580; oil on canvas, 93.5 x 91.5 cm; Florence, Uffizi Galleries, inv. 1898) |

|

| Rosalia Novelli, Immaculate Madonna and St. Francis Borgia (1663; oil on canvas, 200 x 160 cm; Palermo, Chiesa del Gesù di Casa Professa Central Directorate of Religious Affairs and for the Administration of the Worship Buildings Fund of the Ministry of the Interior) |

|

| Margherita Volò, Vase with Flowers and Garland of Flowers (1685; oil on canvas, 116 x 106.5 cm; Varallo, Palazzo dei Musei, Pinacoteca, inv. 3424-2014) |

|

| Giovanna Garzoni, Canine with Biscuits and a Chinese Cup (1648; tempera on parchment, 275 x 395 mm; Florence, Uffizi Galleries, inv. Pal. 4770) |

|

| Giovanna Garzoni, Quince and Lizard (c. 1650; tempera on parchment, 154 x 187 mm; Private Collection) |

|

| Artemisia Gentileschi, David with the Head of Goliath (1630-1631; oil on canvas, 203.5 x 152 cm; Private collection) |

|

| Artemisia Gentileschi, Mary Magdalene (1630-1631; oil on canvas, 102 x 118 cm; Beirut, Sursock Palace Collection) |

Closing is entrusted to the most celebrated artist in the exhibition, Artemisia Gentileschi (Rome, 1593 Naples, after lagosto of 1654), a personality, however, too complex to be effectively exhausted in six paintings (plus one by her father, the St. Cecilia of Perugia). There are, however, several elements of definite interest: the first is the possibility of seeing a painting from a private collection, a Madonna of Milk, recently attributed to Artemisia. Rediscovered in 2015, it had so far been shown only at the exhibition that in some ways constitutes the precedent for The Ladies of Art, namely the Les Dames du Baroque exhibition held in 2018 at the Museum voor Schone Kunsten in Ghent, curated by Tapié himself. The second is the presence of the David rediscovered in 2020 and exhibited to the public for the first time. The third is perhaps the main novelty, the Magdalene Sursock, shown at the Palazzo Reale after the 2020 Beirut explosion that severely affected it (and it is very interesting to observe the damaged work before it undergoes restoration), and on the occasion of the exhibition convincingly attributed to Artemisia Gentileschi by Riccardo Lattuada, who signed the catalog entry.

The section on Artemisia thus constitutes an opportunity to take stock of the latest news concerning the painter, and is one of the reasons why the exhibition Le Signore dell’Arte is worth a visit, if one decides to overcome the prejudice arising from a title that seems to conform to the need to appeal to a wide audience rather than to that of restoring the real dimension of the thirty-four women on display, true and talented artists who lived in an era of profound transformations in the role of women, rather than “ladies of art,” an anachronistic expression to say the least. The absence of vertical insights into aspects related to the social history of women in art between the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries or the idea that intellectuals had about women (for example, Baldassarre Castiglione’s precepts on female education, important as they are, are only touched upon in the catalog) is compensated for by the breadth of the scope, as there are many (though not all) women artists represented, and the scarcity of drawings is answered by the possibility of seeing often unique works and artists whose documented or known works are exceedingly few. It is clear, although the topic had perhaps deserved a more extensive treatment, that for ancient historiographers style was linked to the sex of the author: Baldinucci, after all, spoke of a donnesque hand, before that Vasari could not exempt himself (given the cultural patterns of the time) from associating the concepts of grace and beauty with the manner of female artists, and so on. Above all, it is empirically evident that the absence of traditional education allowed women to experience, in Tapié’s words, “a freedom in the construction of the image that recurs with striking similarities from one artist to another.”

For so many of the women artists in the exhibition, it is also a matter of laying the groundwork for future investigations: this is the case, for example, for Rosalia Novelli, for Claudia del Bufalo, or for Francesca and Giovanna Volò (for the latter, scholar Gianluca Bocchi announces in the catalog a forthcoming paper that will focus on the distinctive elements that separate Giovanna’s production from Francesca’s, and that will propose the reconstruction of an initial corpus of autograph paintings). Finally, one of the merits of the review, especially if we consider the larger section of the public and less accustomed to studies on women’s art, lies in its ability to contribute to demolishing the idea (admittedly already largely outdated in critical debate, but not so widespread among the general public) that the female presence in the history of art of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries is linked to isolated or secluded cases, and capable of arousing wonder: on the contrary, it is a presence certainly not as consistent as the male one, but nevertheless constant, capable of emerging and imposing itself among contemporaries, which has become the subject of study only in recent years and therefore will still have a great deal to tell.

The author of this article: Federico Giannini

Nato a Massa nel 1986, si è laureato nel 2010 in Informatica Umanistica all’Università di Pisa. Nel 2009 ha iniziato a lavorare nel settore della comunicazione su web, con particolare riferimento alla comunicazione per i beni culturali. Nel 2017 ha fondato con Ilaria Baratta la rivista Finestre sull’Arte. Dalla fondazione è direttore responsabile della rivista. Nel 2025 ha scritto il libro Vero, Falso, Fake. Credenze, errori e falsità nel mondo dell'arte (Giunti editore). Collabora e ha collaborato con diverse riviste, tra cui Art e Dossier e Left, e per la televisione è stato autore del documentario Le mani dell’arte (Rai 5) ed è stato tra i presentatori del programma Dorian – L’arte non invecchia (Rai 5). Al suo attivo anche docenze in materia di giornalismo culturale all'Università di Genova e all'Ordine dei Giornalisti, inoltre partecipa regolarmente come relatore e moderatore su temi di arte e cultura a numerosi convegni (tra gli altri: Lu.Bec. Lucca Beni Culturali, Ro.Me Exhibition, Con-Vivere Festival, TTG Travel Experience).

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.