The history of theaters (and their wonders): what the photo exhibition in Palermo looks like

“In Sicily we can’t make it, because Sicily is a difficult land.” In an off-the-cuff statement by Antonio Calbi, curator of Patrizia Mussa’s photographic exhibition Teatralità - Architectures for Wonder, at Villa Zito in Palermo (through Sept. 6, catalog Silvana Editoriale & Studio Livio) there is all the sense of the epic accomplished by the man who this “difficult land” essayed it until a few years ago as superintendent of Inda in Syracuse.

A “return” in continuity, then, that of Calbi, in that same land instead “easy” for the usual blockbuster exhibitions on Impressionists, Warhol and Caravaggio. These months in Sicily there are as many as two underway, a few kilometers from each other, Caravaggio’s Sicily in Noto and Caravaggio: the truth of light in Catania, in which there is very little of the Lombard master. The important thing is to place him in the title-mirror for the larks. From the second one Luigi Ficacci, former director of the ICR in Rome, to which his name had also been approached as curator, kept dissociating himself. That it would almost have been more convincing to find him at Palazzo Zito, the Caravaggio with its scarlet curtains and spotlights cutting diagonally across the scene.

Closed parenthesis: to narrate through images, in this case, through photographs, theatrical architecture in a museum space (Villa Zito is home to the Fondazione Sicilia’s picture gallery) also means recovering to the theater its dimension as a museum archetype in a congenial context. In this conceptual premise alone, the exhibition (with which Maria Concetta Di Natale, one of the greatest Sicilian art historians of all time, makes her debut as president of the Sicily Foundation) convinced us. The museum, like the theater, is the place of performance participation. The idea of how it was necessary to “engage” was already perfectly matured in the Greek world. In Athens the distribution of buildings observed precise optical laws: the relationship between dislocation of temples and minor buildings within the Acropolis was not random; on the contrary, the figure/background scenographic effects between the Propylaea and the Parthenon, between the latter and the Erechtheion were studied. Umberto Albini in 1991 recalled that the Greeks invented almost everything that makes theater. It was rightly observed that Greek theater represents the first organized and coherent realization of modern Western mental space.

The intrigue between museum and theater continues even beyond the centuries, becoming a constant in the 16th-17th centuries, when they are seen as both places where something is exposed to the gaze. It is no accident that the first book on museology, written by Samuel de Quiccheberg and published in 1565, is entitled Museum sive theatrum.

Di Natale emphasizes the also documentary nature of the exhibition, “which traces the history and transformation of theaters not forgetting the wonders of Sicily.” There is, in fact, precisely a section dedicated to “Ancient Theaters of Sicily in the collection of prints and drawings of the Sicily Foundation,” curated by art historian Sergio Troisi. These are prints, drawings and travel volumes that in the golden age of the Grand Tour, between the late 18th and early 19th centuries, made a decisive contribution to the rediscovery of the Sicilian archaeological sites of Catania, Calatafimi, Segesta, Syracuse and Taormina. Alongside celebrated vedutists such as Houel and the travel notebooks of Spencer Compton, there are never-before-exhibited engravings by 18th- and 19th-century painters, landscape painters and lithographers such as Benoist, Berthault, Chatelet, Coiny Debris, De Morogues, Gigante, Leicht and Marinoni.

The central core of the exhibition, on the other hand, consists of more than seventy large-format images that offer a path of analysis on the architectural-decorative and scenic conformation of theaters throughout Italy, filtered through Patrizia Mussa’s personal sensibility: places deputed “to exercise the imagination,” writes curator Calbi, beginning precisely with that of the artist-photographer.

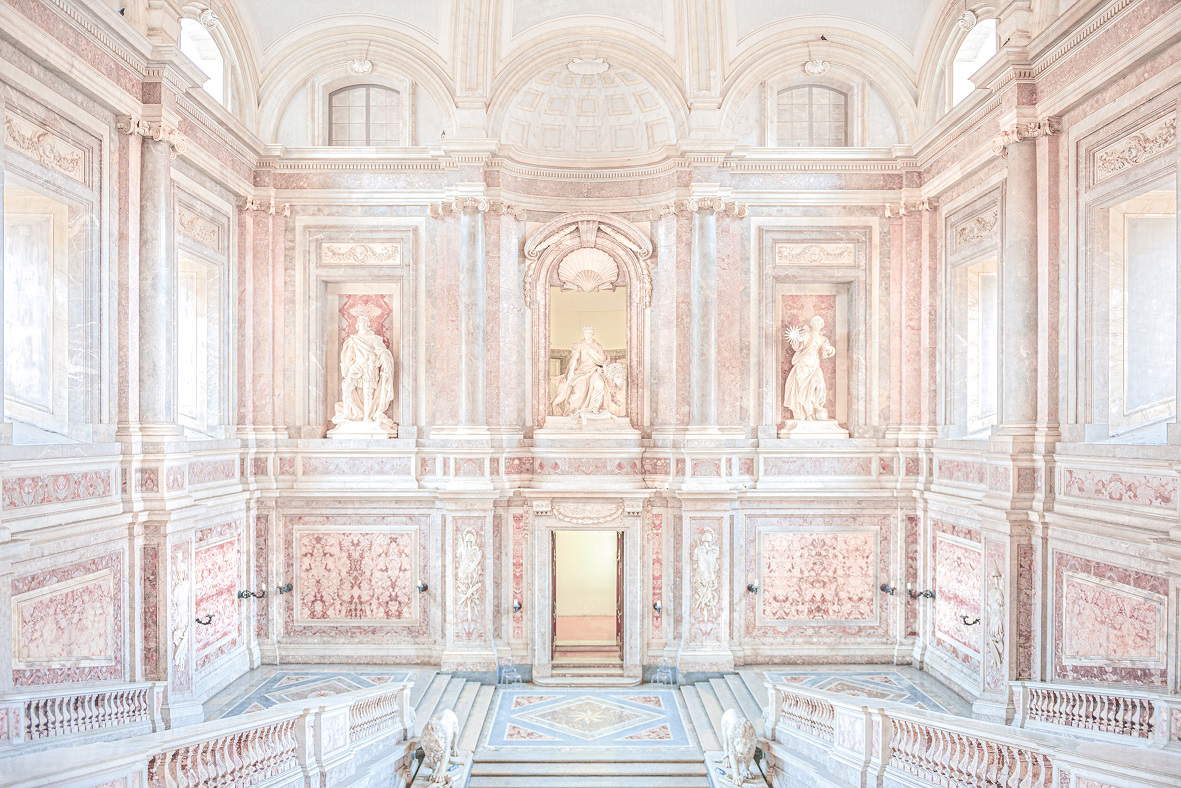

Thus, before the visitor’s eyes flow the photographs of the Greek Theater of Segesta, the first non-provisional theaters of Vicenza, Sabbioneta (Mantua) and Parma, which mark the transition from court theaters to actual buildings, the Teatro alla Scala in Milan, the San Carlo in Naples, La Fenice in Venice, Regio in Turin, or even the Teatro Argentina in Rome, the Pergola in Florence and the Massimo in Palermo. There are also some buildings or monumental complexes that testify to the “theatrical” vocation of certain Italian civil architecture, such as the Reggia di Venaria, that of Stupinigi, the Reggia di Caserta, Palazzo Grimani in Venice; but also of some religious buildings, such as the Chiesa del Gesù in Palermo.

Wandering through the rooms is almost a game of Flemish references where the relationship that binds the two main elements of the theatrical event - the actor and the spectator (in truth more evoked through his absence, than represented) - is complicated by the presence of a third component: the observer, the visitor to the exhibition.

To someone no longer very young, something of a retro flavor in the retouching of photographs cannot escape. After fixing the view and making the print on cotton paper, Patrizia Mussa in fact intervenes with colored pastels on the details. The photographs, thus, almost act as a pendant to the tempera paintings from the Foundation’s collection on display. They bring to mind the extensive (and not infrequently invasive) interventions that, from the earliest times, were applied to photography to improve the result. Techniques largely applied to portraiture, but not only to portraiture. The purpose was to make images look more natural and make them easier to see. Retouching had been invented by a German photographer named Hampstein, who demonstrated it in the 1855 Paris Exposition. In this case it was in black and white and was intended to mellow the subject. Mussa’s purpose, on the other hand, is not coldly ameliorative, but to intervene on the photograph with a creative gesture that confines the images to a dimension almost of metaphysical abstraction, reinforced by the absence of human figures, giving them the feeling of an eternal silence. Existing and at the same time ideal theaters, such as the Ideal City at the Galleria Nazionale delle Marche in Urbino.

Conceived as a traveling exhibition (it will continue with stops in Rome, Vicenza and, in spring 2025, in Paris, in the rooms of the 18th-century Hôtel de Galliffet, home of the Italian Cultural Institute), Theatricality - Architectures for Wonder is an exhibition project still “in the making.” The architectural photographer is, in fact, planning to complete it with other famous Italian theaters. For the exhibition at Villa Zito it has already been enriched with new works, compared to those with which it debuted at the Royal Palace in Milan last December: In addition to the Greek Theater of Segesta and the Church of Jesus, already mentioned, the Politeama Theater in Palermo, the 18th-century Villa Palagonia in Bagheria and the 18th-century Teatrino that, in the early ’1900s, Ottavio Lanza di Branciforte, prince of Trabia, took with him to Paris by having it dismantled from Palazzo Butera and which is now set up in the Paris headquarters of the Italian Embassy in France.

Among the many “architectures for wonders” selected, a few absences are noticeable, such as that of the first modern theater in European history, the Teatro Farnese (1618) within the monumental complex of the Pilotta in Parma, the subject of a recent musealization project. Formerly reduced to a backdrop for the entrance to the National Gallery, it is now a venue for events and performances. Also missing is the gem of the “smallest theater in Italy” with its 100 seats, a refined “hidden” jewel inside the 18th-century Palazzo Donnafugata in Ragusa Ibla. Who knows, hints to further enrich this original project “in crescendo.”

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.