In a letter dated May 10, 1548, Annibal Caro expresses to Giorgio Vasari his desire to take possession of one of his works, suggesting that it would be better if the work were done with some haste: not so much because Annibal Caro was in a hurry (and, in the event, he had managed to find a brilliant justification for it anyway), but because he was convinced that things born of “furore,” understood as a poetic impulse, are those that succeed best, an assumption that is as valid for painting as it is for poetry, to the point that Caro does not hesitate to tell his friend “that you are as much a poet as a painter.” The Horatian concept of ut pictura poësis that emerges explicitly from Annibal Caro’s letter is central not only to thoroughly enjoy that Theater of Virtues put in the title of the exhibition that Arezzo is dedicating to its artist this year to mark on the calendar the four hundred and fiftieth anniversary of his death, but also to understand more fully fullness of Giorgio Vasari’s personality, to understand who was that personage whom today the general public tends to consider mainly for his historiographical work or, at most, for some of his paintings on which our eyes have fallen during a visit to some museum, but who in reality stands as a decidedly more complex figure, and not only for his versatility. To get an idea, one could do an exercise: try to imagine who might be, say, a Giorgio Vasari of the 21st century. What job would the Giorgio Vasari at the height of his career do today. We could imagine him, if we want to trivialize, as a film director (for today, a Vasari would not paint, since painting in 2024 is certainly not the most relevant art in public discourse), a visionary director, an effervescent animator of cultural debate, a filmmaker capable of carving out a role for himself as an intellectual (we imagine him writing in newspapers, participating in talk shows, publishing books), with a keen interest in the history of cinema (indeed: a filmmaker who establishes a revolutionary theory of cinema), often engaged in the creation of institutional campaigns, prone to forays into the other arts in which he was trained, without neglecting pronounced skills as a marketing man, as a great communications expert. And even imagining such a figure we would still not have a complete idea that corresponds to Vasari’s perception of himself: the discrepancy is due, we might say, to the public image of the artist in the sixteenth century.

Before Vasari, in spite of the claims of visual artists and in spite of the considerable prestige that painters, sculptors, and architects had seen progressively recognized for at least a century and a half, there was no theoretical codification of the visual arts as we might understand them today: painting, sculpture, and architecture were still the “manual ingenious arts,” as Vasari himself defines them in the Life of Giovanni Antonio Sogliani. And it is with Vasari that the definition, coined by him, of “the arts of drawing,” under which the Aretine would bring together painting, sculpture and architecture, becomes the foundation of an aesthetic theory determined to recognize the visual arts as having the same prerogatives as letters, poetry, the “liberal arts,” to use an anachronistic expression. “Painting and poetry use the same terms as sisters,” he wrote in his own Reasonings. And from this desire for recognition also derives Vasari’s versatility: “Rade volte un ingegnoso è eccellente in una cosa che non possa facilmente apprendersi alcun’altra, e massimamente di quelle che sono alla prima sua professione somiglianti, e quasi procedente da un medesimo fonte” (so instead in the Vita dell’Orcagna). The prerogative of Vasari’s aesthetic theory is, as is natural to expect, the Horatian dictum, albeit in reverse to how the ancients understood it, who spoke of poetry by comparing it to painting, whereas in modern times it did. Paul Oskar Kristeller observed as early as 1951 that this “ambition of painting to participate in the traditional prestige of literature also explains the popularity” of the concept of ut pictura poesis, “which asserts itself forcefully for the first time in the treatises on painting of the 16th century and would retain its appeal until the 18th.”

Vasari came to formalize his idea at a relatively late stage of his career, but we must imagine it in nuce from the very beginnings if we are to read one of his earliest known works, the celebrated Portrait of Duke Alessandro de’ Medici , which opens the Arezzo exhibition together with Vasari’s own portrait by Stradano, as a long celebratory poem written with the tools of painting, brushes and colors: here then is the shining armor as a metaphor for the “mirror of the prince” since “the prince should be such that his people could be mirrored in him in the actions of life” (it is Vasari again who provides, in the Ragionamenti, a kind of paraphrase of his portrait), he sits on a round chair because the circle indicates his perpetual reign, a dominion that has no beginning and no end, and then the seat is swaddled with a red cloth that alludes to the blood shed by the Medici against his enemies, the helmet is not worn by the duke but is laid on the ground as a sign of peace, and so on. Vasari’s quality that immediately emerges from the Arezzo exhibition, curated by Cristina Acidini with Alessandra Baroni, beyond his uncommon communicative skills that were immediately put at the service of the Medici, is his ability to elaborate novel iconographies, a quality that must be read in the light of his theoretical ambitions: the exhibition gives immediate proof of this by devoting a good half of the room on Vasari’s training (the Temptations of St. Jerome stand out here, moreover, which together with the portrait of Alessandro de’ Medici constitute another excellent loan from the Uffizi, on which one could go to great lengths to linger on the admirable juxtaposition of sacred and profane motifs that Vasari deploys on his panel) to theAllegory of Patience, an iconographic motif born at the table, elaborated by Vasari, with the participation of Michelangelo and Annibal Caro himself, to fulfill a request of the bishop of Arezzo, Bernardetto Minerbetti.

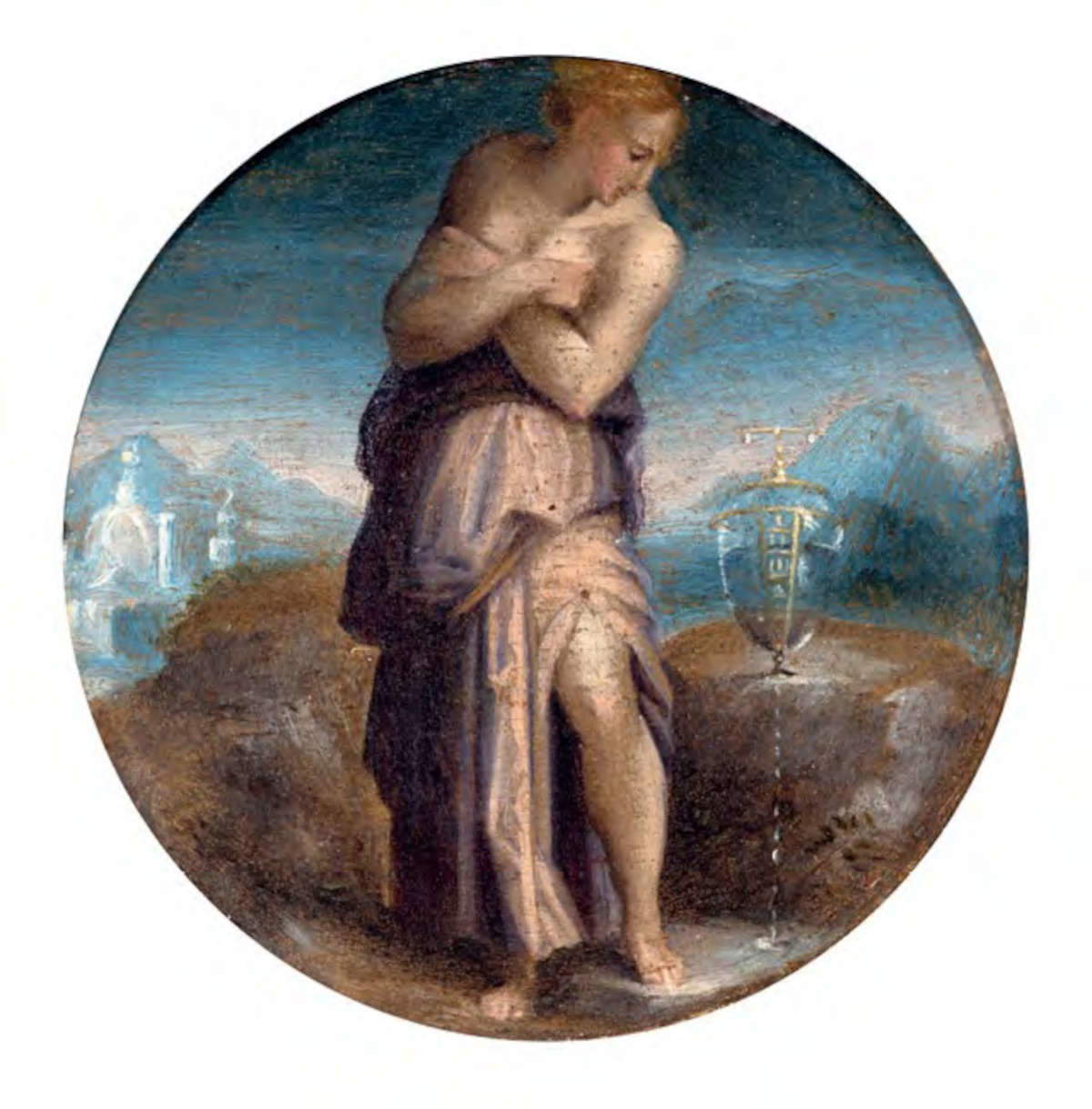

TheAllegory of Patience, writes Carlo Falciani, who dedicated an essay to it in the exhibition catalog, represents a unicum “among Vasari’s allegories especially because of its anomalous simplicity and the park-like use of symbols that distinguishes it.” the original, now in a private collection (a smaller replica is seen at the exhibition, displayed along with a variant also by Vasari’s hand and a large canvas that echoes it, attributed on this occasion to Bastianino, but only a decade ago attributed to the collaboration between Giorgio Vasari and Gaspar Becerra: Vasari’s invention was especially fortunate in Ferrara because the patron was in close contact with Ferrara personalities), departs from any traditional depiction of patience in order to propose an original reading of it that could satisfy a twofold need, namely, on the one hand, to set itself up as a model, an eventuality of which Bishop Minerbetti had spoken at dinner with Cardinal Ippolito II d’Este, who had chosen Patience as his enterprise, and on the other hand to create an image that could also be representative of the vicissitudes of its patron. Patience is thus rendered by Vasari as a naked woman, arms folded (a quotation from Michelangelo’s Last Judgment , probably suggested by the old artist himself) to emphasize her disposition, caught watching a drop falling from a water clock and patiently waiting for it to consume the rock to which the woman is chained (although the chain does not always appear), all closed with a motto by Annibal Caro, “diuturna tolerantia.” The unprecedented iconography, essential and provided with few attributes in deference to Michelangelo’s thought, which preferred to emphasize attitudes rather than accessories, thus arose from the collaboration between a young artist, a poet, and an old artist (who was also a poet, as is well known), and would not be an isolated case in Vasari’s production: his art often benefited from joint work with literati especially in the context of court appointments.

A whole section of the exhibition, the one on the “apotheosis of virtue,” which begins just after the chapter on the Chimera of Arezzo brought back to the city where it was found in Vasari’s own time, dated November 15, 1553, is centered on the allegories that Vasari produced for Duke Cosimo de’ Medici (but not only: also exhibited here is the Forge of Vulcan executed for Prince Francesco) and on the artist’s commitment to enriching with new meanings those virtuous principles that moved his art and animated his very existence, so much so that this “theater of virtues” of his sustains the scaffolding of the review from the very title: “that Vasari was a learned artist [...] was and is well known,” writes Acidini, but “that in his painting he poured endless and very subtle quotations drawn from a vast universe of known, lesser-known and even peregrine and rare symbols, composing images laden with allegorical meanings, was long perceived as a scholarly burden. More a disturbance to the beauty of painting than an added intellectual value.” The most recent research has therefore focused on the interpretation of his visual apparatuses and the complex of references, literary quotations, and allegorical implications that permeate Vasari’s images and contribute to making the Aretine’s works complicated visual poems, often challenging for contemporary critics given that over the centuries the understanding of the codes useful for deciphering the allegories has gradually faded. We are helped, however, by the fact that we are left with texts useful for understanding the meaning of his images: among them, the works of Vincenzio Borghini, a highly cultured Benedictine monk who established a robust intellectual association with Vasari, the subject of a dense essay by Eliana Carrara published in the exhibition catalog. It is in Borghini’s Zibaldone that the description of the allegories now preserved in the collections of the Fondazione Cassa di Risparmio di Firenze, all of which are on display in the exhibition, are preserved.These allegories were once part of the artist’s Florentine home (although we do not know how they were arranged) and are related to the splendid allegories that Vasari painted for the ceiling of Palazzo Corner Spinelli.

And it is Borghini again who illuminates the meaning ofOblivion and Dream that we see depicted in the two wonderful drawings that have come on loan from the Metropolitan in New York: oblivion is thus a woman lying on the ground and leaning against a vase from which the water of the River Lete flows, the river of forgetfulness in Greek mythology, the one into which the souls of the Elysian Fields plunged in order to lose the memory of their past lives (the demons fluttering in the sky above the female figure hugging the vase allude to the cares and torments that oblivion allows one to forget). Sleep, on the other hand, is a winged woman putting a young man to sleep while above him hover some cherubs holding mirrors, an allusion to the illusory deformations that reality takes on while dreaming. Vasari kept faithful to Borghini’s ideas, albeit making a few modifications (for example, Borghini suggested representing sleep as a damsel full of eyes: Vasari avoids any monstrosity instead) and thus preserving a certain autonomy of thought that inevitably went in the direction of the autonomy of the visual arts that he himself hoped for and that later in his career he would advocate with increasing conviction. This new self-consciousness might be one of the elements to keep in mind when, following a visit to the exhibition, one is reminded of the unusual episode of Federico Zuccari’s Porta Virtutis , displayed at the close of the section on a par with his Calumny by Apelles, especially to remind the visitor how theVasarian allegorism fascinated younger artists, as well as to highlight the relationship between Zuccari and Vasari (they were collaborators and Zuccari was also Vasari’s successor, but there was no shortage of friction between the two): nevertheless, it should be noted that perhaps an artist would hardly have gone so far as to orchestrate an operation of public discrediting of one of his patrons and opponents (the Porta Virtutis originated as a polemical painting against Pope Gregory XIII’s scalco, Paolo Ghiselli, who had rejected a work he had commissioned from Zuccari, deeming it shoddy, and assigning the commission to the Bolognese painter Cesare Aretusi) if he had not matured a new perception of his own status.

Not even sacred art escaped the continuous reinvention of symbols and allegories to which Vasari subjected traditional depictions. To see the most admirable fruit of his creativity, it is necessary to leave the Galleria Comunale and visit the section set up in the former church of Sant’Ignazio, for which the archdiocese of Florence has obtained the loan of one of Vasari’s cornerstones, the successful Allegory of theImmaculate Conception, an extraordinary product of the imagination of a Vasari who as early as 1540, commissioned by Bindo Altoviti, was fine-tuning the new iconography after lengthy consultations with friends and scholars including the learned Giovanni Lappoli, known as Pollastra, canon of Arezzo Cathedral and tutor to the artist himself: Vasari had devised a new, singular image that addressed the term of Mary’s sinless conception by merging two passages from the Bible, the one from Genesis in which God curses the serpent for tempting Adam and Eve, and the one from Revelation in which the “woman clothed with the sun with the moon under her feet and on her head a crown of twelve stars” is described. For Vasari it was an extraordinary success, since he was asked for several replicas and the invention was copied, and the circumstance probably suggested that he continue to apply to sacred works and altarpieces that allegorical language that was so congenial to him, also drawing from not so obvious sources: Interesting in the exhibition is the comparison between the Tetravangelo of Rabbula, a very rare 6th-century Syrian codex that was donated to Clement VII before 1534 and then came to the Laurentian Library before 1573, and the Crucifixion with the Madonna, St. John and St. Mary Magdalene, in which Vasari takes up a topos of ’Byzantine origin, that of the sun and moon included in the scenes of crucifixion and mourning over the dead Christ to signify the grief of all creation for the death of Jesus, the same situation seen in the unique Pietà between the sun and the moon at Palazzo Chigi Saracini in Siena (where, in the two stars, the mythological figures of Apollo and Diana also appear). The same figuration is found in the illuminated crucifixion scene on the Tetravangelo, a circumstance that has led curator Acidini to speculate that Vasari had access to the codex "given the Medici affiliation [...] and his arrival in Florence in the span of the artist’s life and activity; and it is suggestive conjecture that he took a direct view of the sheet with the Crucifixion, where the darkened and mournful heavenly bodies stand out." More traditional, but no less intense and thoughtful, are other paintings that occupy the section on sacred art, such as the recently discovered Christ Carrying the Cross and the unpublished Holy Family, both owned by the Esteves family, works in which Vasari, while formally unexceptionable and while painting works of the finest quality (just look at the intensity of the Christ) sticks to more conventional figurations.

Closing the itinerary of the visit is a rich room on drawings and a section devoted to the Accademia delle Arti del Disegno, established in 1563 at the behest of Giorgio Vasari himself with the aim of training young people in the practice of art, and soon also becoming a kind of workshop of ducal commissions: Vasari’s creation stands as the first formal academy for artists in history, a model for all academies to come, which was also established with the specific intention of equalizing the status of artists with that of men of letters and intellectuals. In the exhibition, the early years of the Accademia delle Arti del Disegno are retraced through the works of various artists who joined Vasari’s association, with particular emphasis on paintings that, as part of the project supporting the exhibition, address the theme of the virtues that guide the artist in his work: it is especially worth lingering on the works that implicitly pay homage to Michelangelo’s symbol of the three crowns (i.e., painting, sculpture and architecture), which, writes Alessandra Baroni, “represents a clear reference to Medici Florence, particularly that of Cosimo, founder and generous benefactor of the important institution.” It is a sort of modern logo, which we find in the unpublished Allegoryof Virtues and Occasion, by Michele Tosini and a collaborator, in Giovanni Stradano’sAllegory of Virtues and the Academy , and then again in Stradano’sAllegory of Temperance, Justice and Liberality , also by Stradano, a logo whose meaning Vasari himself, in the Life of Michelangelo, illustrates: “three crowns or truly three circles intertwined together, in such a way that the circumference of the one passed through the center of the other two reciprocally. Michelagnolo used this sign, either because he intended that the three professions of sculpture, painting and architecture were interwoven and bound together in such a way that the one gives and receives from the other comfort and ornament and that they cannot and should not stand out as a whole, or also that as a man of high intellect he had a more subtle understanding of them. But the academicians, considering him in all three of these professions to have been perfect, and that the one helped and embellished the other, changed his three circles into three crowns entwined together, with the motto: ’Tergeminis tollit honoribus,’ wanting therefore to say that deservedly in said three professions he is due the crown of supreme perfection.”

Emerging from the Theater of Virtues set up for this year’s anniversary is a Vasari perhaps all too underestimated by the general public, which has all too often relegated him to his role as historiographer: from the halls of the exhibition rises, if anything, the figure of an artist who, from the very beginning of his career, did not hesitate to elaborate an aesthetic theory from which would originate a concept of “art” which is the one that has come down to the present day, an artist firmly convinced that the arts were all sisters and that their differences were expressed only in the variety and diversity of their means of expression: the “theater of virtues” that accompanied his entire career can be seen as a kind of translation in images of a thought that Vasari would later organize with more theoretical systematicity in Lives, if we want the first modern theory of art.

Of course, the Arezzo exhibition is not the first to explore Vasari’s protean genius and his universe, nor is it the first to highlight (albeit somewhat implicitly, in this case) the importance of his figure in the history of Western art. Perhaps never before, however, has such a vertical emphasis been placed on the process of image and model construction that produced most of the masterpieces for which the artist from Arezzo is known. Vasari. The Theater of Virtues is, in essence, the exhibition to read Giorgio Vasari’s masterpieces beyond their surface. And it will be worth pointing out that the purpose of this solid, very valid exhibition also has a lot to do with our actuality, with our reality as people living in an age of abundant visual overproduction, targeted by a continuous, incessant deluge of images, surrounded by mediocre content, propaganda, fakes, products of artificial intelligence: the invitation, moreover declared, that the exhibition addresses to us, is to examine Vasari’s complex apparatuses with the aim of sharpening the critical tools useful to orient us in that “populous universe of icons that today accompany us, surround us, assault us through the most varied and pervasive,” declares curator Acidini, “so as to reveal to ourselves and others the visual devices of political propaganda, social manipulation, commercial persuasion and more.” Decoding images, in short, and above all tracing them back to their origins, their motives. Vasari could not be more timely.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.