by Federico Giannini (Instagram: @federicogiannini1), published on 23/11/2017

Categories: Exhibition reviews

/ Disclaimer

Review of the exhibition 'Sign Alphabet. Barnils, Capogrossi, Perilli, Pijuan', at CAMeC La Spezia from November 4, 2017 to January 7, 2018.

In 1961 Feltrinelli released one of Gillo Dorfles’ best-known texts, the seminal Ultime tendenze nell’arte di oggi: the first chapter of the essay, intended to offer readers a compendium of contemporary art from the postwar period onward, was entirely devoted to what Gillo Dorfles called"sign painting.“ ”It is a fact,“ the great critic wrote, ”that starting from the immediate postwar period, in various countries and art centers, in Paris as in Tokyo, in New York as in Rome, a genre of painting based above all on the speed of execution and on the prevalent use of graphically differentiated elements rather than on the laying down of large colored surfaces has come to the fore." The sign artists were considered the most immediate heirs of the Surrealists: the graphic elements that began to populate their works could be read as a spontaneous manifestation of thatpure psychic automatism that Breton considered the most immediate means of expressing the workings of thought. And vain it would be to find any reference to reality, any link to a known figuration, any attachment to the concrete and tangible in the works of the sign painters. Sign, although declined in the most varied ways, according to different sensibilities and often with opposite purposes and inspirations, is nevertheless almost always impulse, is poetry, is much closer to instinct than to rationality. The signs, Gillo Dorfles continued, are “completely abstract, completely devoid of conceptual ’meaning’ (at least evident) and also completely divorced from any reference to pre-existing figurations, whether naturalistic or symbolic in character.”

It is possible, however, to trace common ground, and this is what the exhibition Alfabeto segnico seeks to do, which brings to CAMeC in Spezia, after the inaugural stop at the Fondazione Stelline in Milan, the experiences of four artists of different generations, namely Giuseppe Capogrossi (Rome, 1900 - 1972), Achille Perilli (Rome, 1927), Joan Hernández Pijuan (Barcelona, 1931 - 2005) and Sergi Barnils (Bata, 1954), in order to outline a history of sign painting that goes from 1950 to the present day and demonstrates how relevant it still is (in case the examples of several young artists who, in the years two thousand and ten, have all but abandoned the language of the sign were not enough), especially in the context of a society that, as the curator Alberto Fiz reminds us in the introductory essay, makes wide use of a communication based on signs capable of conveying universal concepts. The user who writes on social networks uses emoticons and stickers to convey emotions, states of mind: it is a universal writing, full of meaning. And the same goes for sign painting: it would be vain to find, in the works of a Capogrossi or a Barnils, a “reference to pre-existing figurations.” Their paintings do not have a plot: they have a sense.

Yet, to unambiguously define what sign is is a very difficult task. “The galaxy of sign,” writes Alberto Fiz, “is so complex that one runs the risk of getting lost”: however, “there is no lack of constants within a cognitive procedure of self-consciousness where the artist imposes his own plot that does not require prior consent from the viewer.” The artist, in other words, creates a kind ofalphabet (hence the title of the exhibition), potentially unlimited, which is his own, which springs exclusively from his feeling, his experience, his emotions, and which, as Corrado Cagli observed when commenting in 1950 on Capogrossi’s works at the time of his “sign turning point,” does not respond to a taste (and therefore, one might add, the sign is a space of freedom), but to a function: the sign, therefore, always includes something ineffable, which pertains solely to the artist’s most intimate sphere, but at the same time is capable of transmitting to observers, within the spaces of a kind of narrative that takes the form of an encounter, “the private part of the ritual without imposing a detachment between subject and object,” as the curator again observes. Thus, to establish the coordinates of the sign, four artists come to CAMeC, two Italians and two Catalans (like Joan Miró, the forerunner of the poetry of the sign), chosen because they are paradigmatic, because they are able to propose a comparison between different historical contexts, because they are also characterized by different points of tangency, because they are moved by a true and profound sensibility.

|

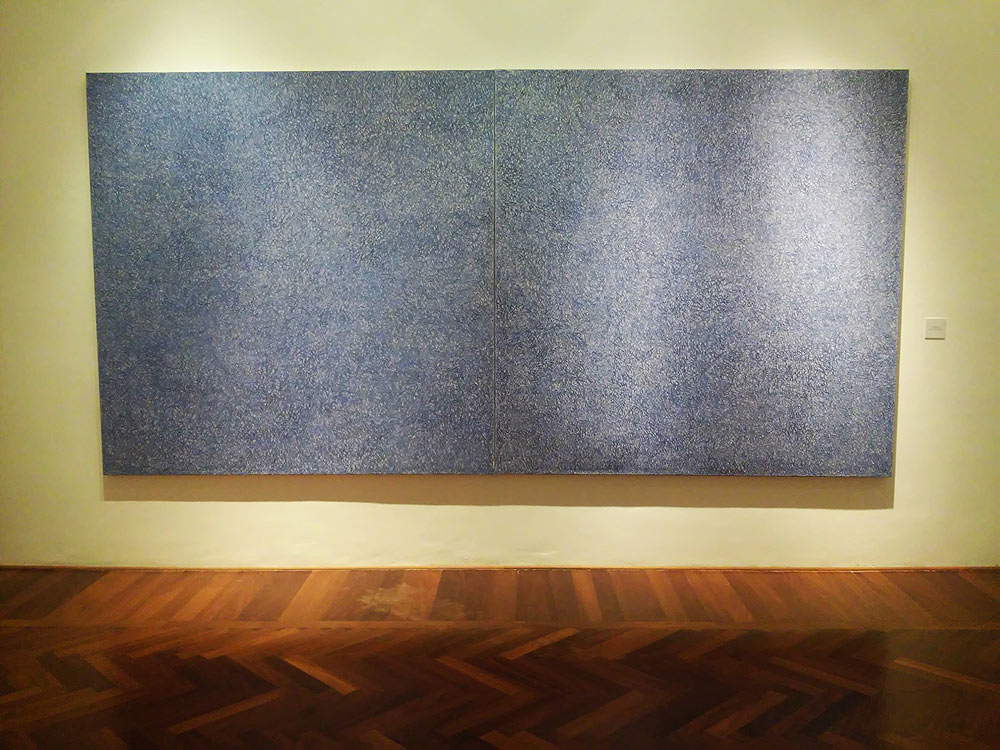

| A room of the exhibition Alfabeto segnico at CAMeC (La Spezia) |

|

| A room from the exhibition Alfabeto segnico at CAMeC (La Spezia) |

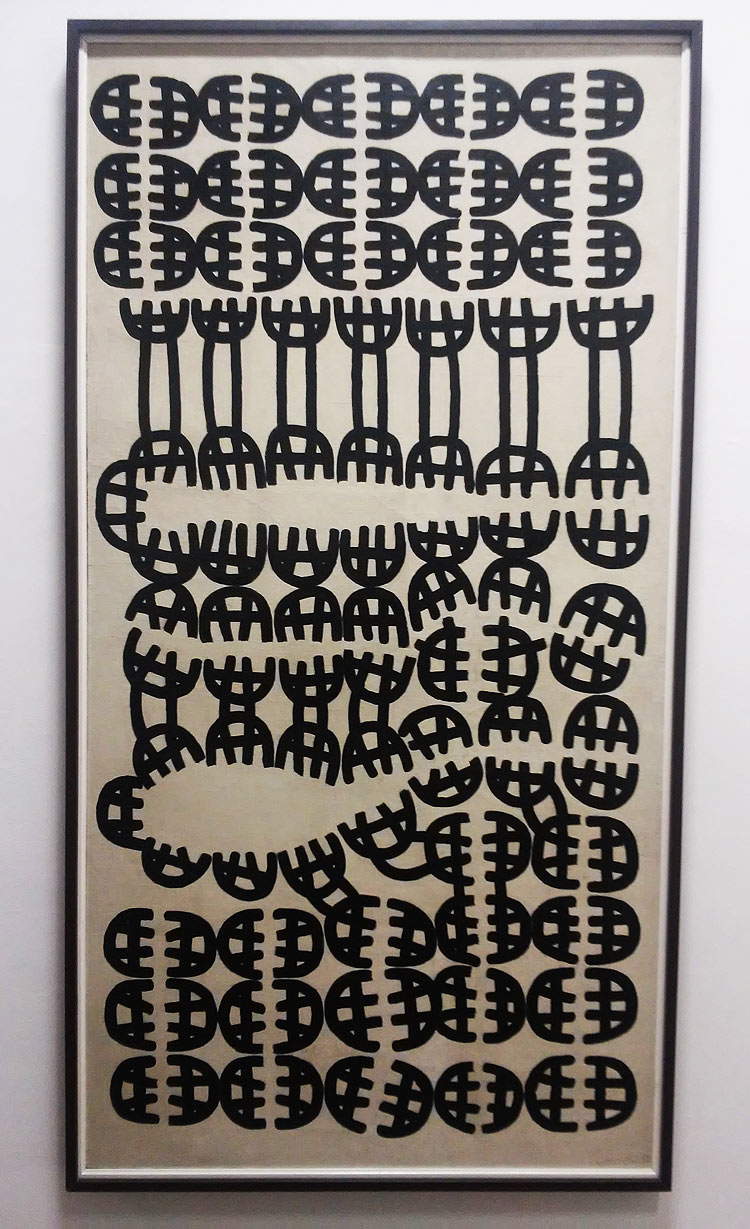

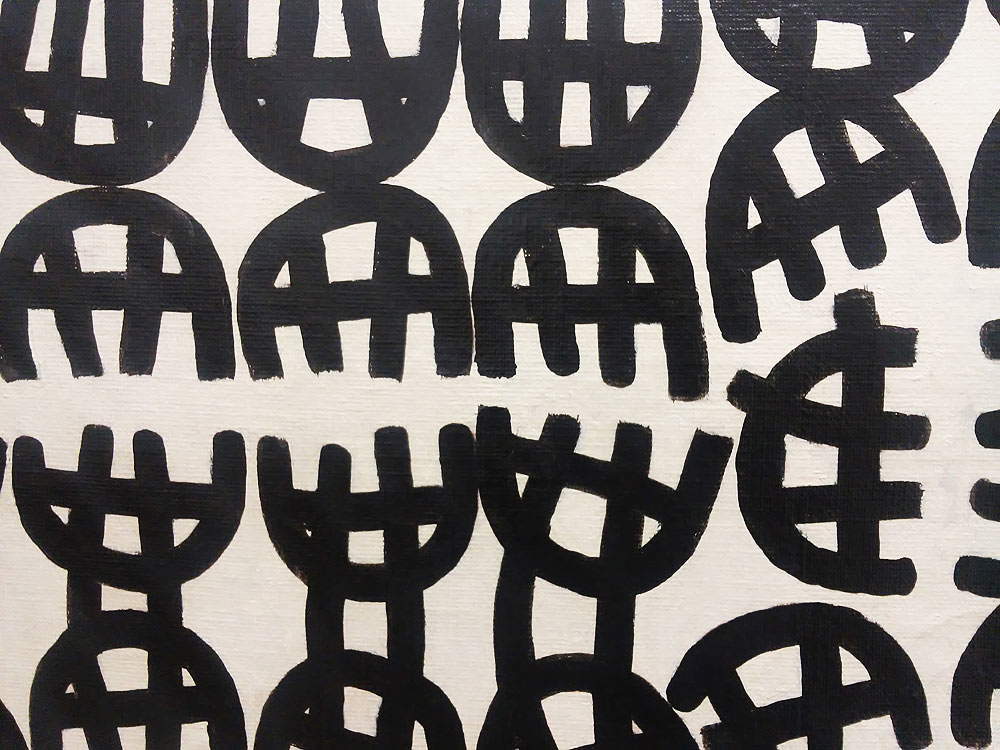

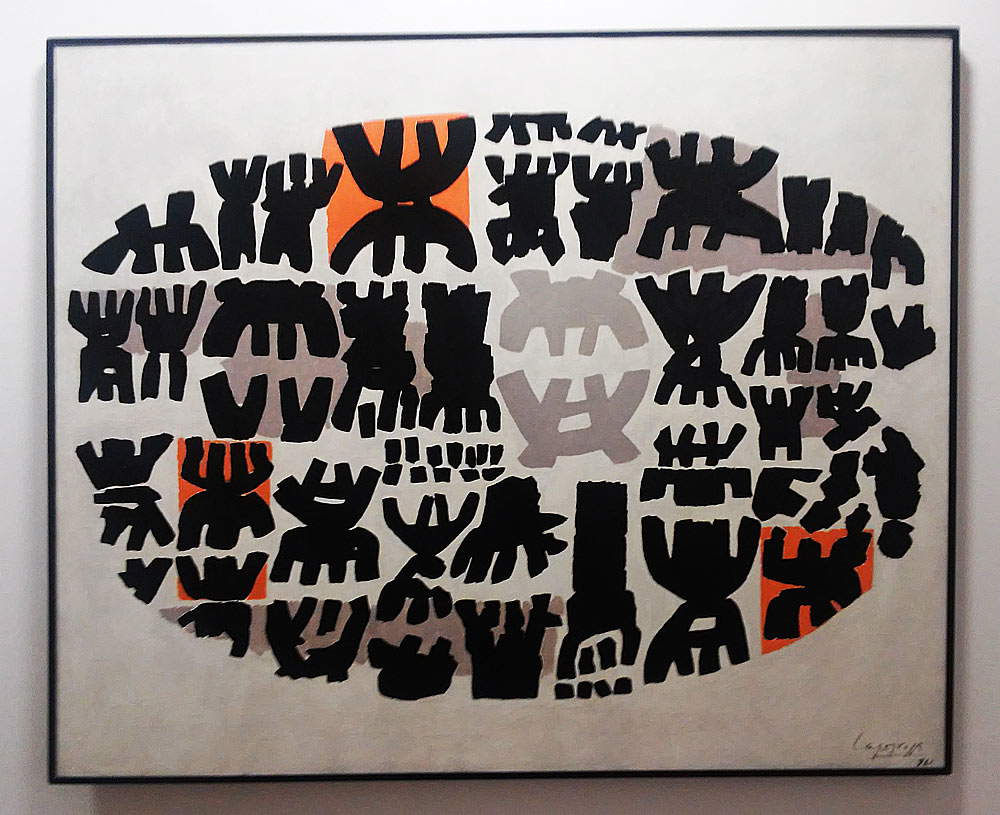

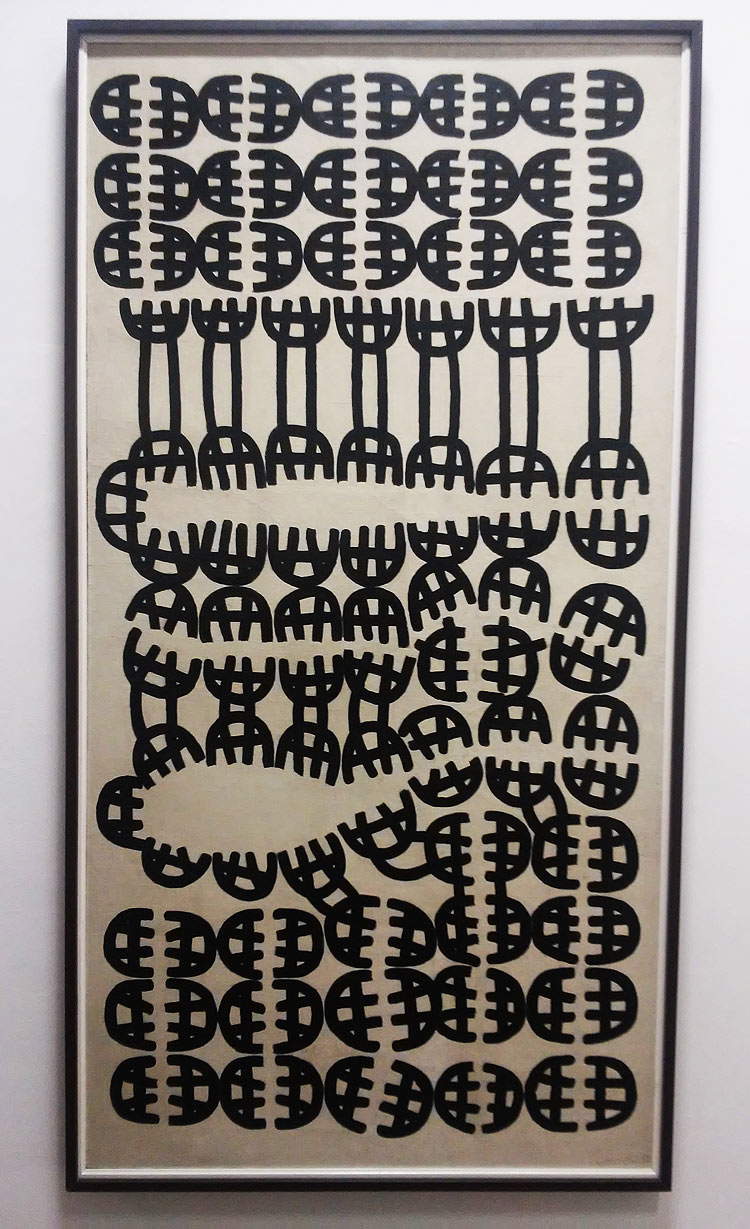

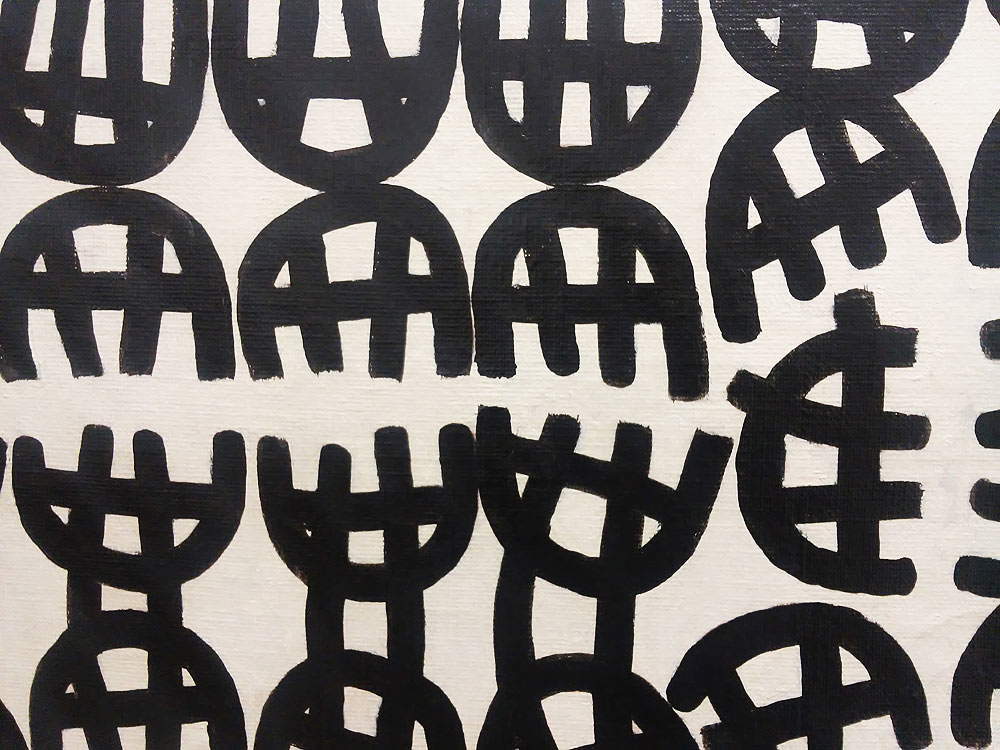

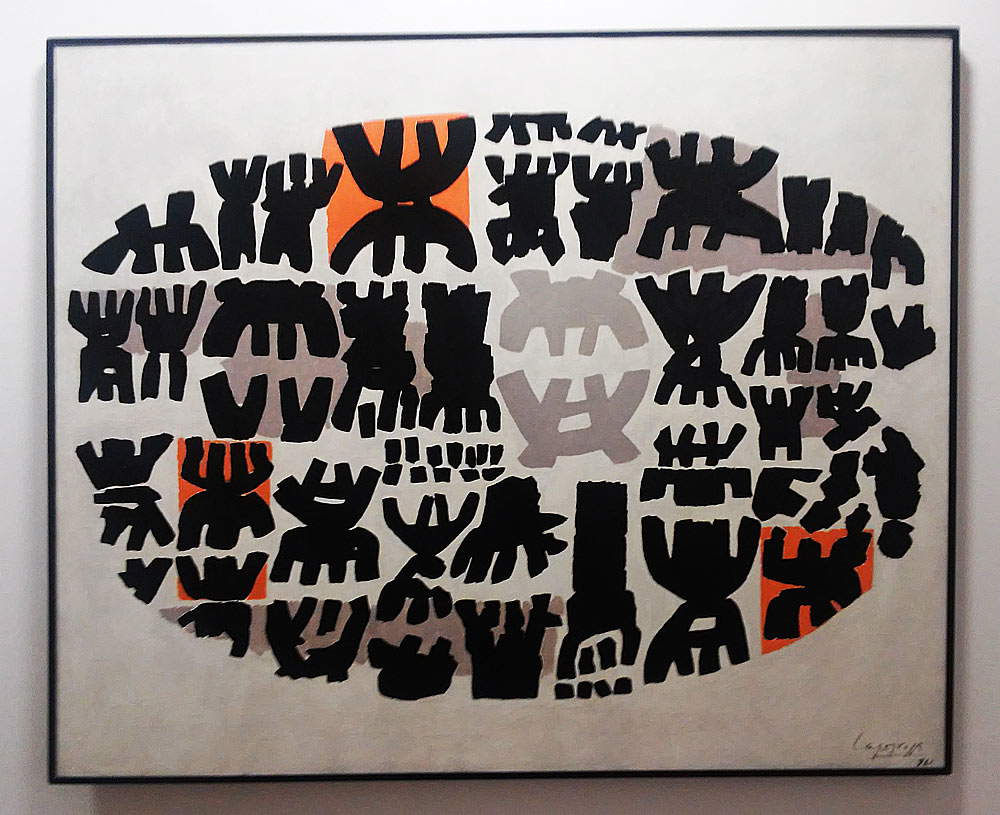

Giuseppe Capogrossi is an artist about whom many have written, and in front of his paintings many have questioned, ever since that fateful 1950 when, at the age of fifty, he presented himself at Galleria Il Secolo in Rome with works that were radically different from what he had produced up to that time: abstract, repeated signs that seemed unfathomable, far removed from the figurative paintings that the painter, trained in the groove of the Roman School, had executed up to that point. Works that were similar to Superficie 678 (Carthage) which comes to the La Spezia exhibition on loan from the MART in Rovereto and which shows the viewer only a repeated black sign on a white field, as if it were a founding element of a code, of a genetic mapping. Those who at the time (and later) tried to attribute to Capogrossi’s typical sign some concrete reference (a trident, a fork, a comb), his son Guglielmo pointed out in 1990, probably did not stand in front of his works trying to assume the same attitude that had allowed the painter to produce similar works. Capogrossi felt the need to express an inner space: in other words, sign was for him a way of expressing a tension, a way of sensing reality while not necessarily referring to it with concrete references. Space, for Capogrossi, was not only that of nature, of reality: there exists, within each of us, a space that is impossible to express with elements that can refer to the sphere of the perceivable. The combinations of this sign are, for Capogrossi, the most suitable means of expressing tensions, emotions, restlessness, harmonies, equilibriums.

Brandi argued that in contemporary art there was nothing more problematic, and at the same time simpler, than Capogrossi’s painting. There are no hidden meanings. Indeed: there are no meanings proper, because everything is contained in that one sign. Brandi himself, in order to explain Capogrossi’s sign, used the effective image of the number one that contains in itself all numbers: the code of the Roman artist, not having to refer to anything, needed nothing more than a basic element, whose iteration would be sufficient to express the artist’s inner space. Thus, the sign is like a molecule, a cell, a musical note, a brick: from its combination come infinite expressive possibilities. And it is interesting to note how the artist gave these paintings the name of Surfaces: because Capogrossi, observed Argan, who dedicated a fundamental essay to the artist, “is convinced that he has annulled the third-dimension, but it does not escape him that the surface can arise only from rightly balanced signs, and he is convinced that it is not necessary to give the general image of space, if space is already contained in the single fragment of his speech. This is Capogrossi’s secret: to renounce space by way of hypothesis, in order to harmoniously study all possible spaces.”

|

| Giuseppe Capogrossi, Superficie 678 (Carthage) (1950; oil on paper applied to canvas, 169 x 88.5 cm; Rovereto, Mart - Museo d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea di Trento e Rovereto) |

|

| Giuseppe Capogrossi, Surface 678, detail |

|

| Giuseppe Capogrossi, Superficie 105 (1954; oil on canvas, 180 x 120 cm; Milan, Galleria Tega) |

|

| Giuseppe Capogrossi, Surface 105, detail |

|

| Giuseppe Capogrossi, Superficie 150 (1956; oil on canvas, 54 x 65 cm; Milan, Collezione Eleonora e Francesca Tega) |

|

| Giuseppe Capogrossi, Surface 154 (1956; oil on canvas, 80 x 100 cm; Intesa Sanpaolo Collection) |

|

| Giuseppe Capogrossi, Surface 399 (1961; oil on canvas, 160 x 196 cm; Rovereto, Mart - Museo d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea di Trento e Rovereto) |

|

| Comparison of Capogrossi and Barnils |

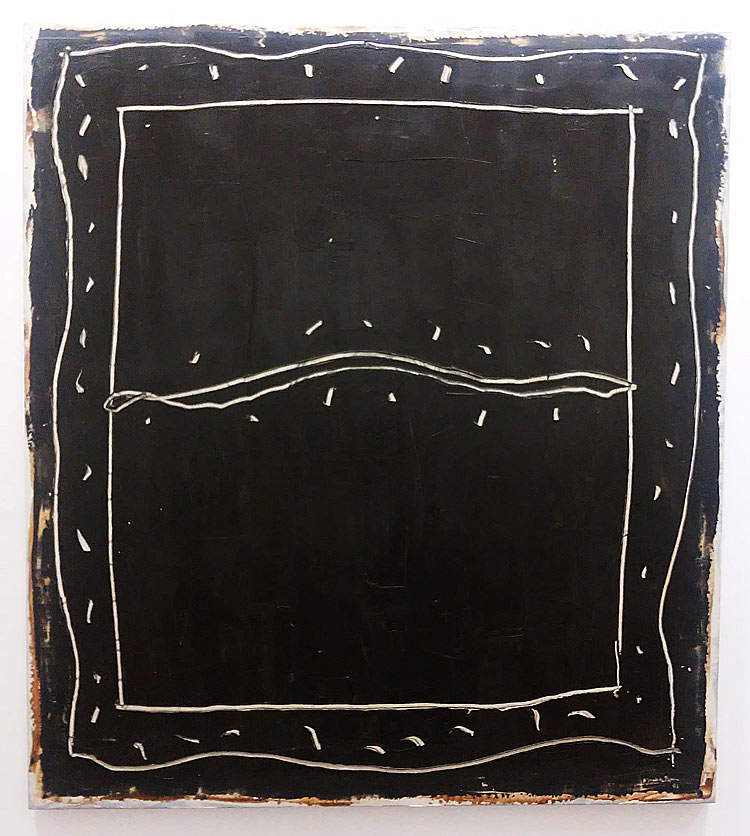

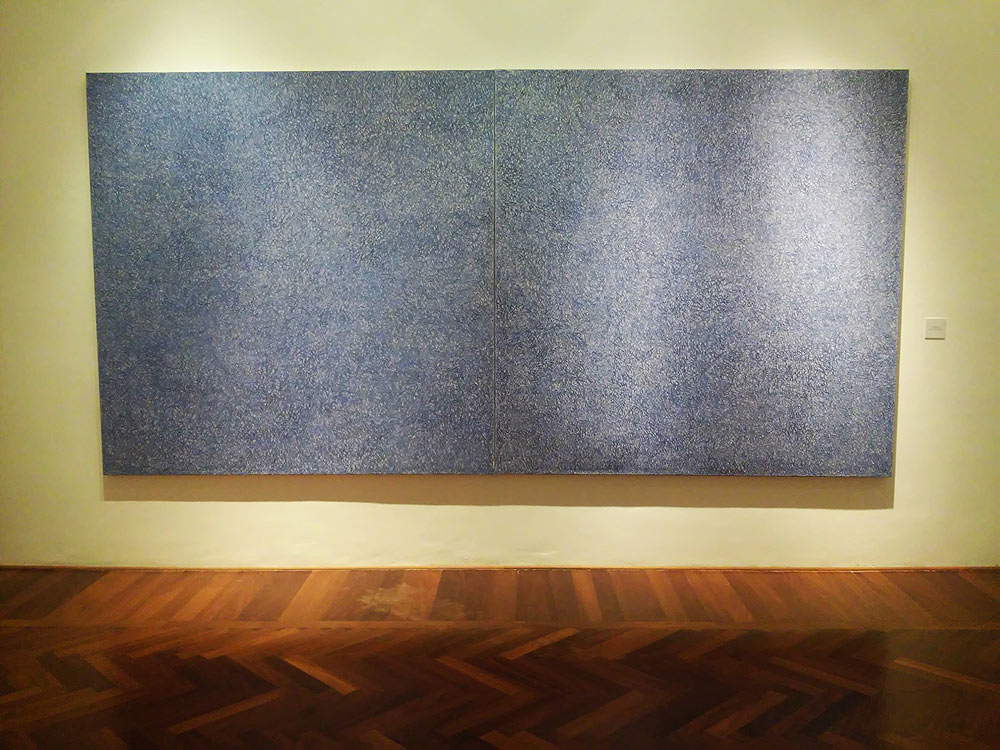

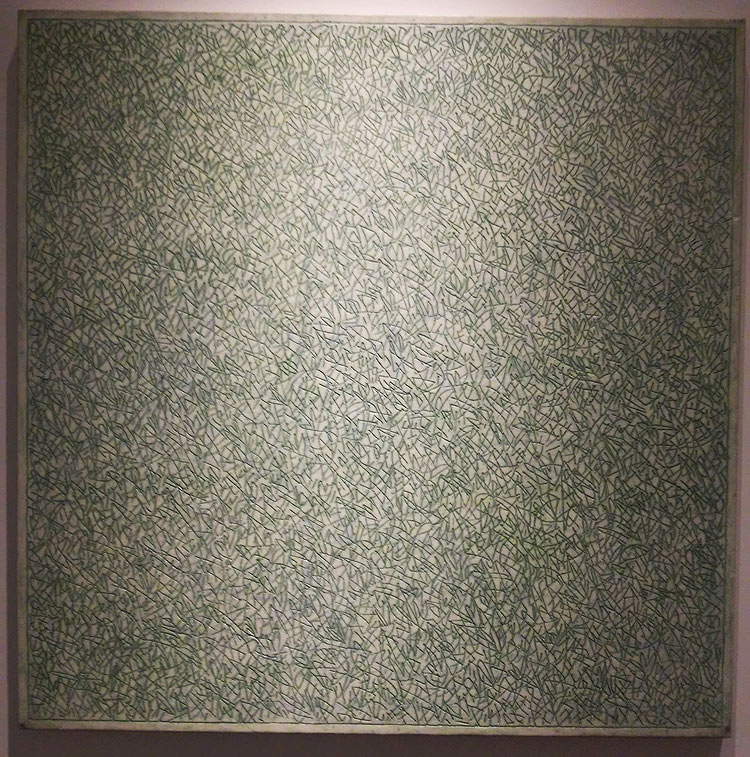

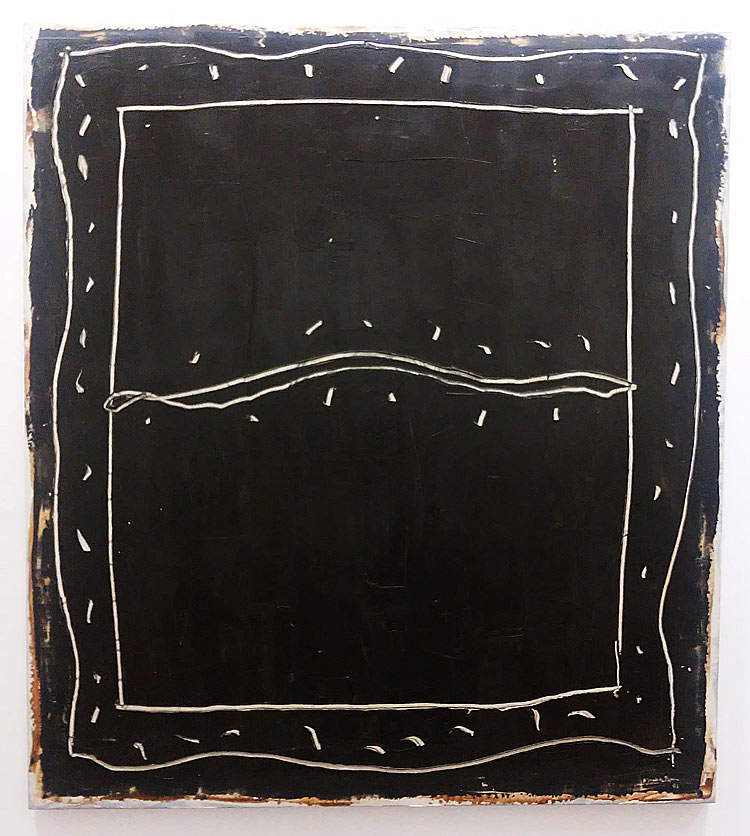

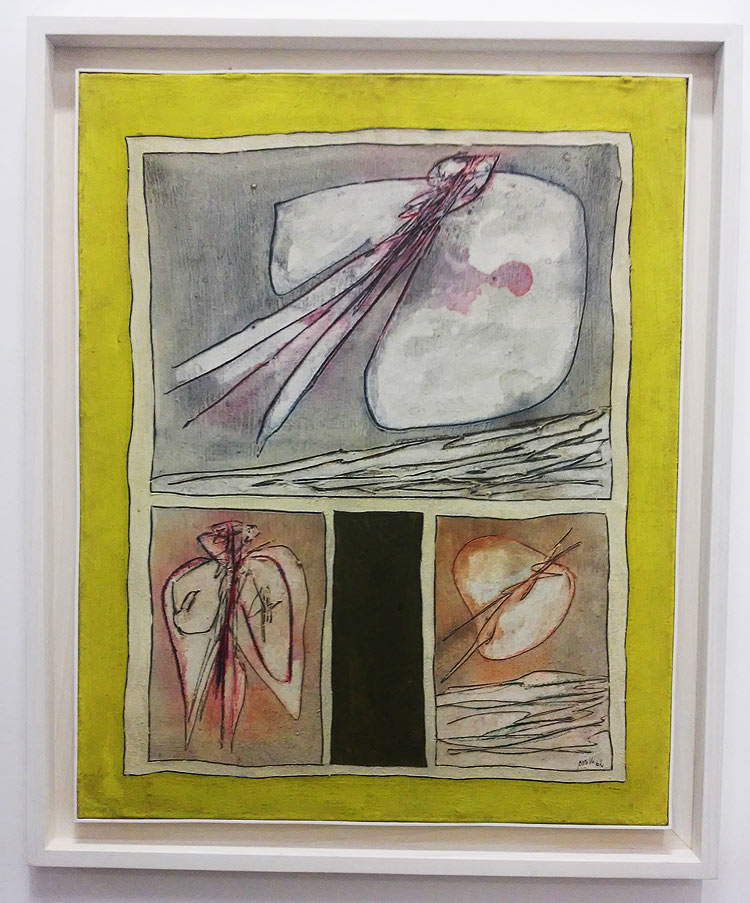

Space is also a fundamental point of Joan Hernández Pijuan’s artistic research. For Capogrossi, space “is an inner reality of our consciousness,” and not dissimilar are the assumptions of Pijuan’s painting, whose aim is to establish a meditative relationship with reality through the reduction of outer space to a kind of inner map, so much so that the Catalan artist considers himself a painter of landscapes. Let us stand before his Camp daurat (“Golden Field”): Pijuan’s sign still has references to reality, but proceeds by abstraction in order to find a meeting point between “I” and "reality." But it is not, Pijuan’s, an intellectual, or conceptual painting. It is simply an emotional painting, born of experience and investigating the processes of memory, knowledge, and imagination. And that it is abstraction in the truest sense of the term can be discovered by looking closely at his works: one will notice that his is a painting that operates “by way of levare,” using an expression usually employed for sculpture. Pijuan creates his landscapes by tracing furrows in the color, digging into the surface, removing matter, as happens in Marc per un paisatge or in Memoria del Sur, paintings in which the elements arise from marks that scratch the backgrounds. It is a painting without a brush, a painting of graffiti that harks back to the primordial days of humanity (Fiz compares it to the rock carvings of prehistory) and is dictated, as was the case for Capogrossi, by an inner necessity. But if Capogrossi’s painting was filled with “signs without meaning,” Pijuan’s starts from reality by investigating its archetypes through a cathartic process: consequently, unlike Capogrossi, who we might call a profoundly secular artist, Pijuan is a contemplative artist.

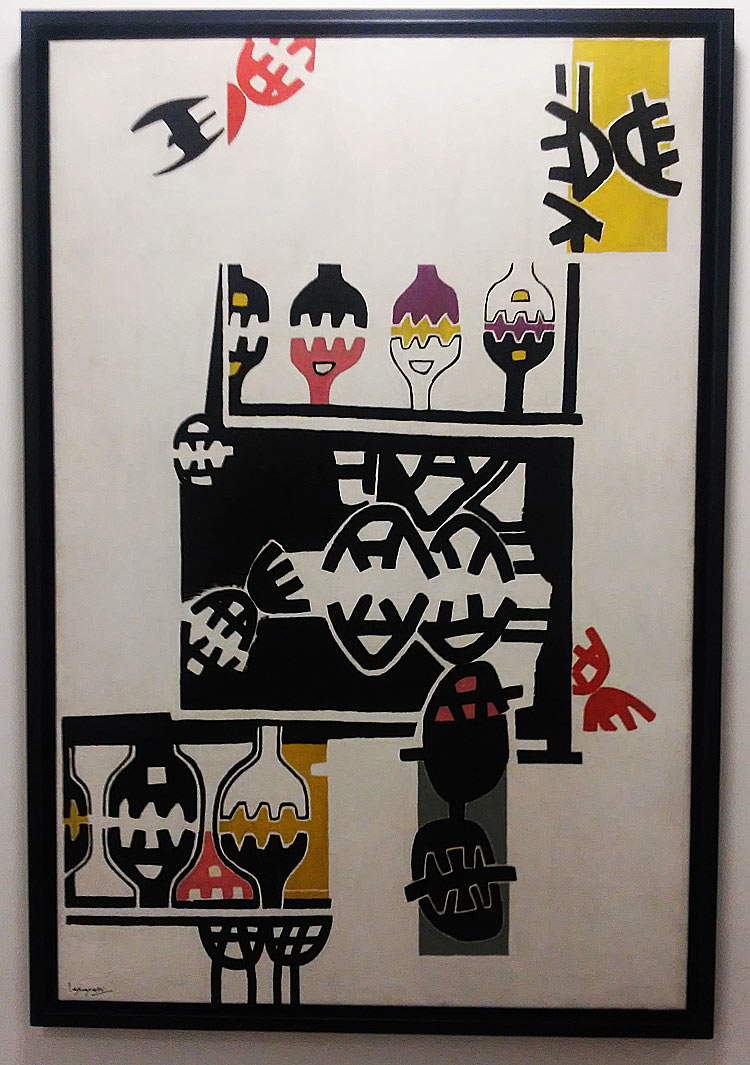

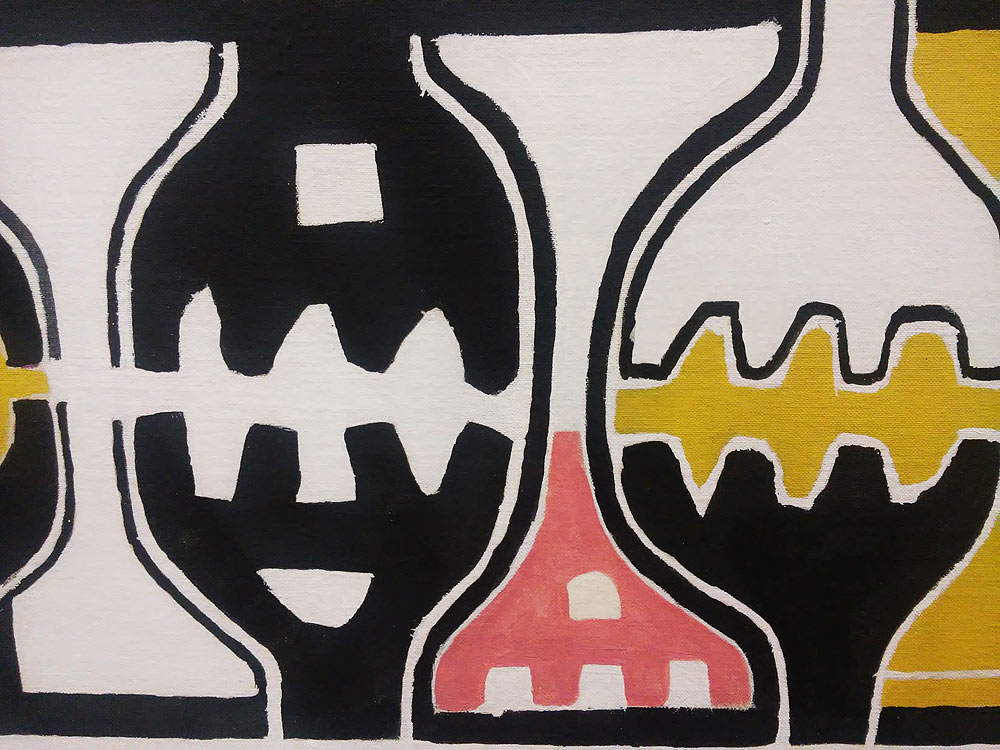

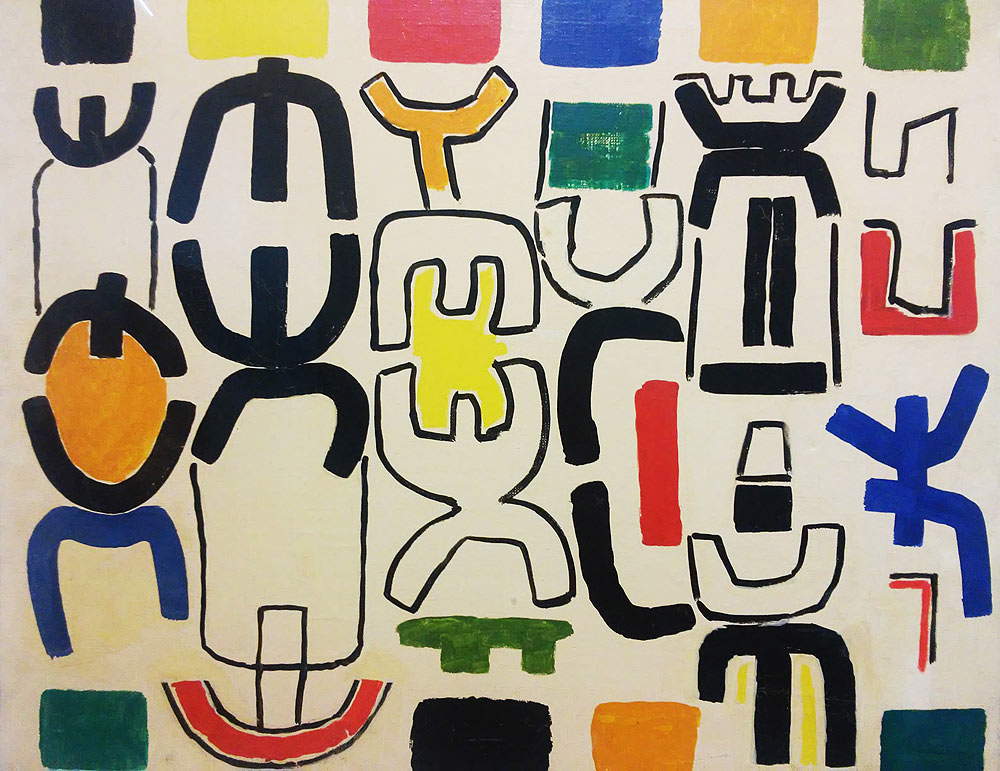

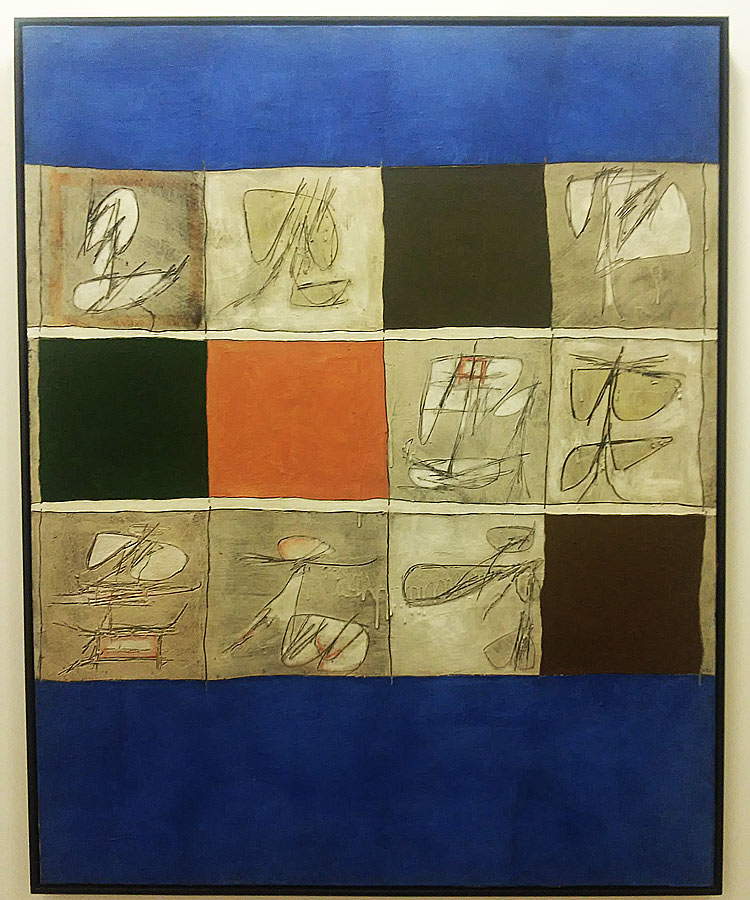

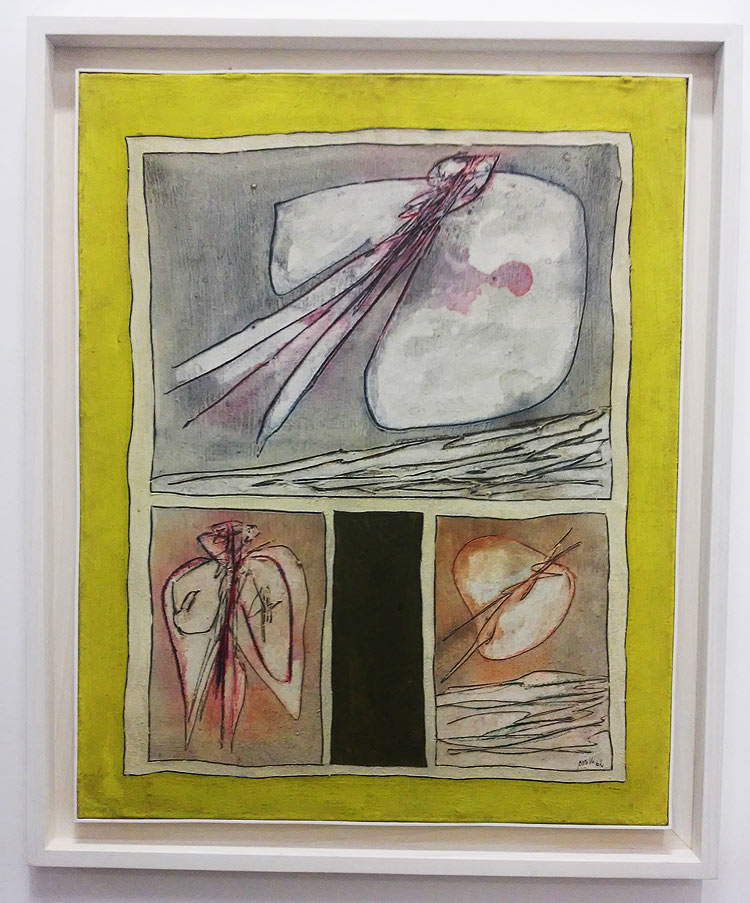

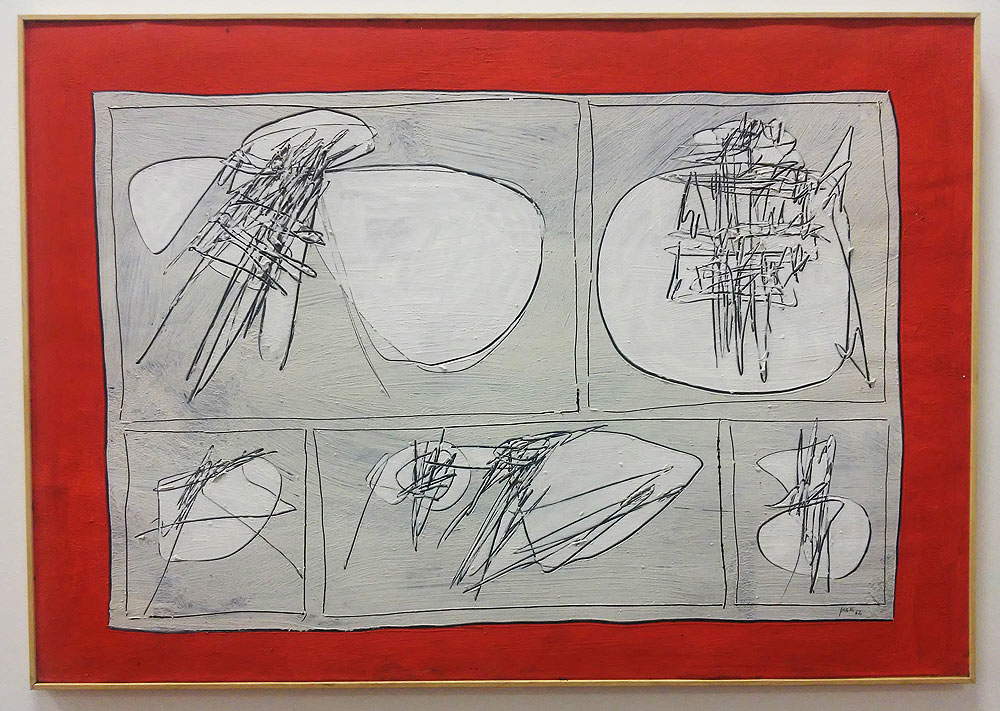

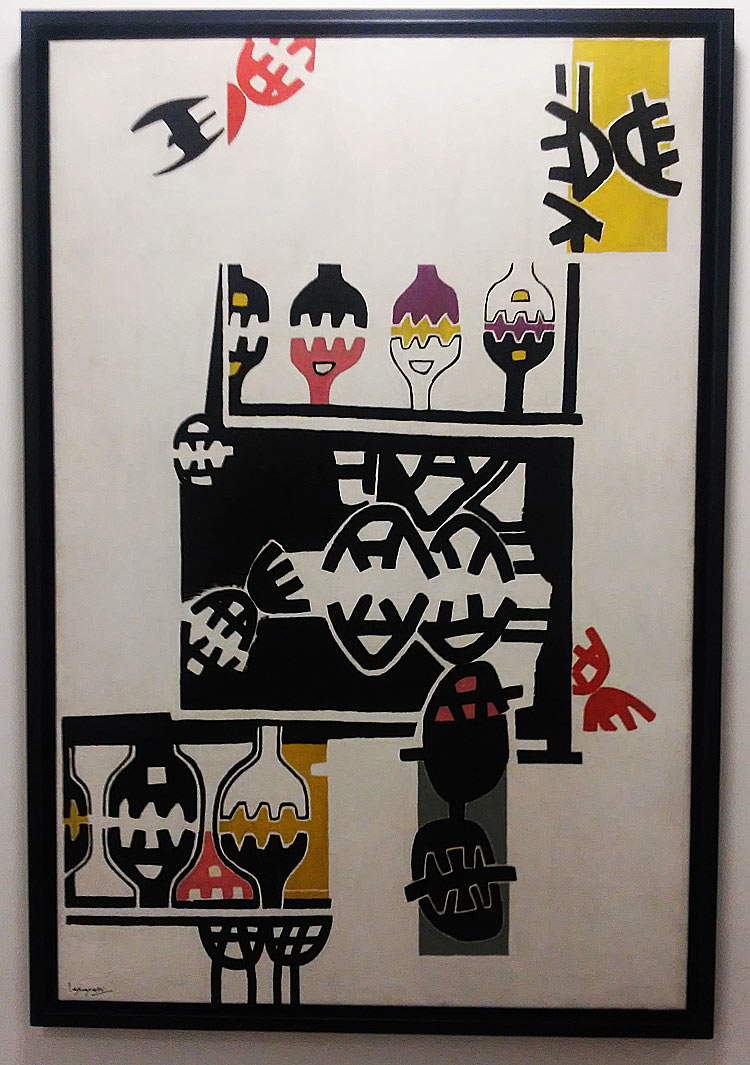

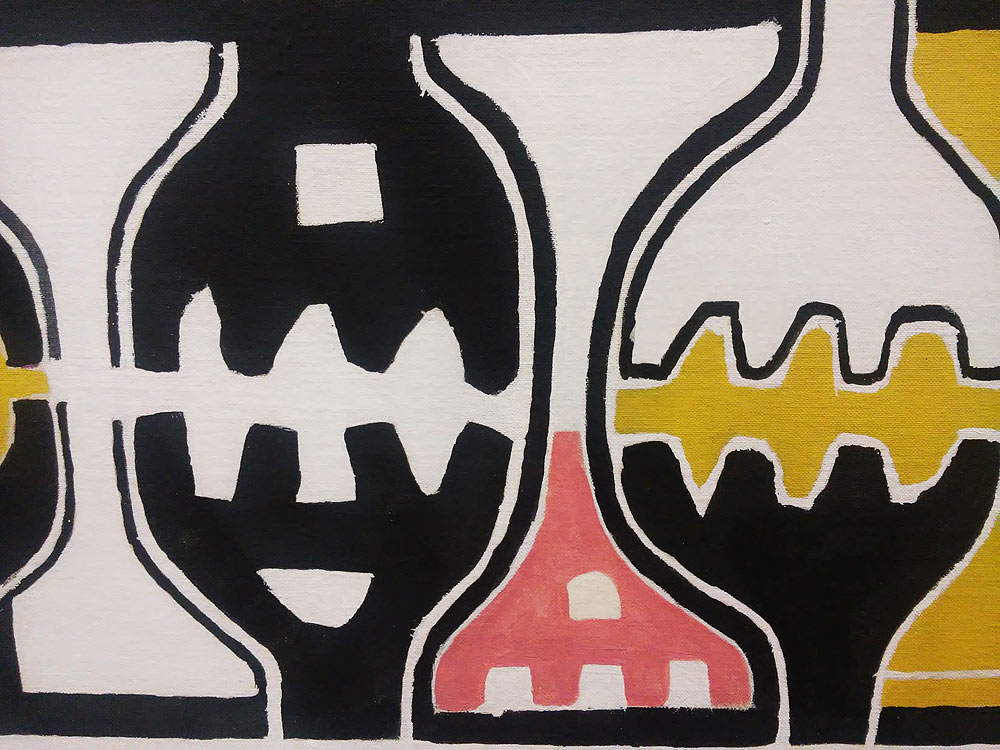

Continuing our visit to the CAMeC exhibition, we find some traits of Pijuan’s painting in that of Achille Perilli and Sergi Barnils. Perilli’s images, with their mysterious graphemes, also call to mind the engravings of the caves of Lascaux or Altamira. That of Perilli, a painter of very high culture, is a kind of childish writing that does not respond to any predetermined order but plays with shapes and colors, the elements that live in the “space of art” (the expression is the artist’s own), the place where the space of the artist and that of the observer meet. Perilli’s art, however, can be considered antithetical to Pijuan’s: the Catalan artist started from a real datum (we have seen it: a wheat field, a hill, a tree, a house) and tried to capture its essence to arrive at a purified image. Perilli, on the other hand, tries to give form to theirrational by framing it in the logic of signs. Interestingly, Perilli has always rejected the label of abstract artist: the need to express the irrational that governs the artist’s self is for Perilli something very concrete. And it is a concrete result that the unconscious produces an image: the rock carvings, which have survived for thousands of years, are there to prove it. And they are there to show also how the all-human need to express itself through images disregards historical and social contexts: it is an impulse. This is perhaps the deepest sense of Achille Perilli’s signs.

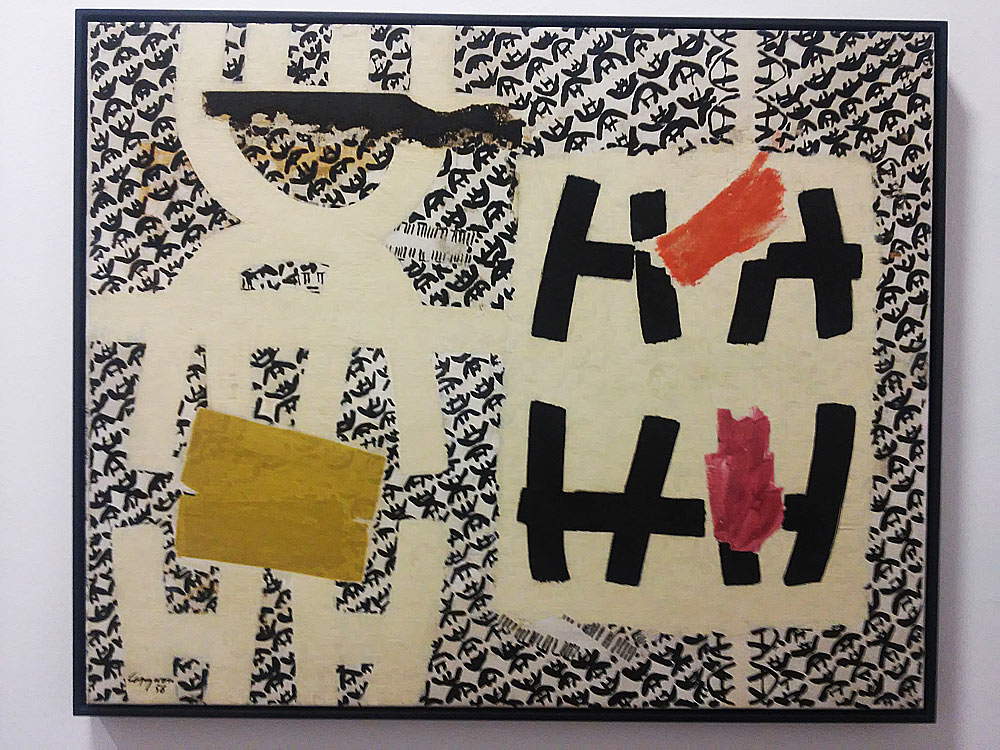

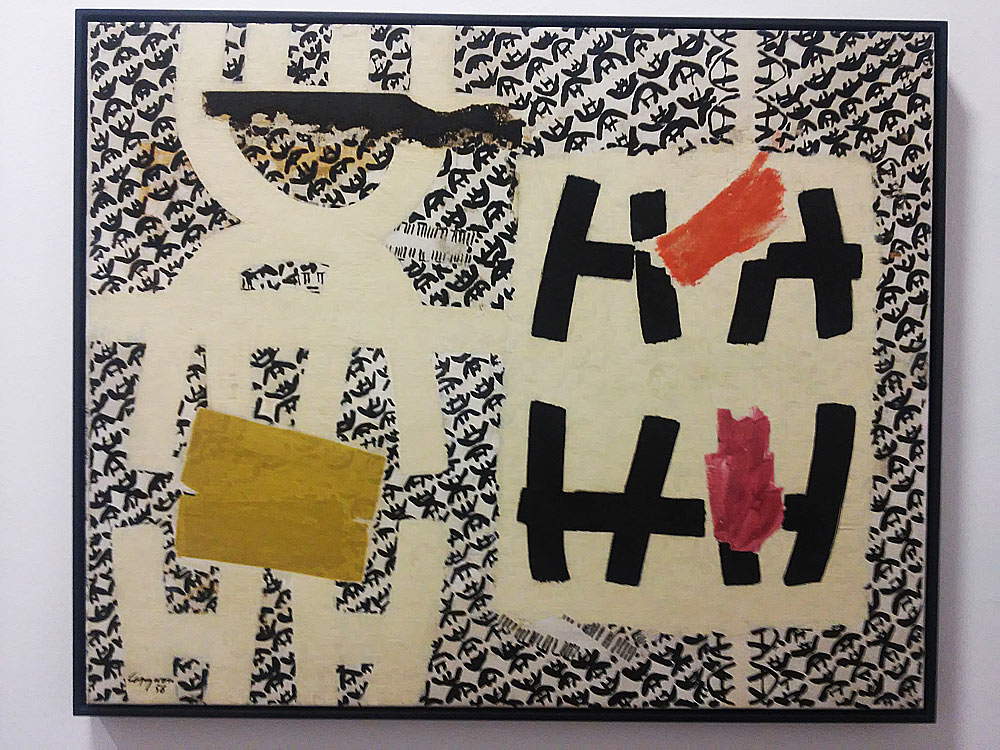

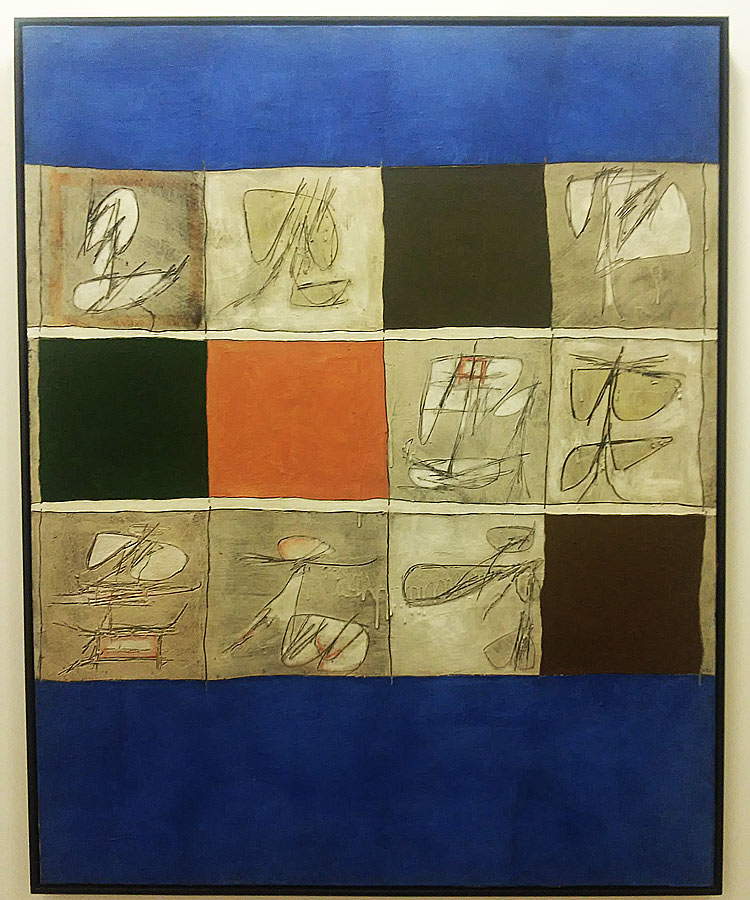

It is an almost instinctive painting, his. A painting that, as it was for Klee (a fundamental artist for Perilli’s path), does not go in search of the rational, of balance, of form: it aspires to function. The CAMeC exhibition particularly insists on a strand of Achille Perilli’s production, that of the so-called “comic strips,” a sort of reinterpretation of American strips: signs are arranged within boxes that visually recall the “strips” of the magazines of the time. The artist’s reflection on the “popular element of rapid consumption” (or at least that is how Gillo Dorfles still interpreted it), her comic strips have, instead of characters, indecipherable signs without identity, which, however, are organized within a narrative scheme: a probable mediation between the irrational element and the idea of wanting to create an art that preserves an important human dimension.

|

| Works by Joan Hernández Pijuan at the exhibition Sign Alphabet. |

|

| Joan Hernández Pijuan, Marc per un paisatge 1 (2001; oil on canvas, 162 x 145 cm; Milan, Private Collection) |

|

| Joan Hernández Pijuan, Camp daurat (2002; oil on canvas, 146 x 114 cm; Milan, Private Collection) |

|

| Joan Hernández Pijuan, Memoria del sur 7 (2002; oil on canvas, 162 x 290 cm; Barcelona, Private Collection) |

|

| Joan Hernández Pijuan, Memoria del sur 7, detail |

|

| Achille Perilli, Cima del vuoto, la solidità del silenzio (1961; mixed media on canvas, 200 x 160 cm; Milan, Galleria Tega) |

|

| Achille Perilli, Top of the void, the solidity of silence, detail |

|

| Achille Perilli, Do ut des (1962; mixed media on canvas, 81 x 65 cm; Milan, Galleria Tega) |

|

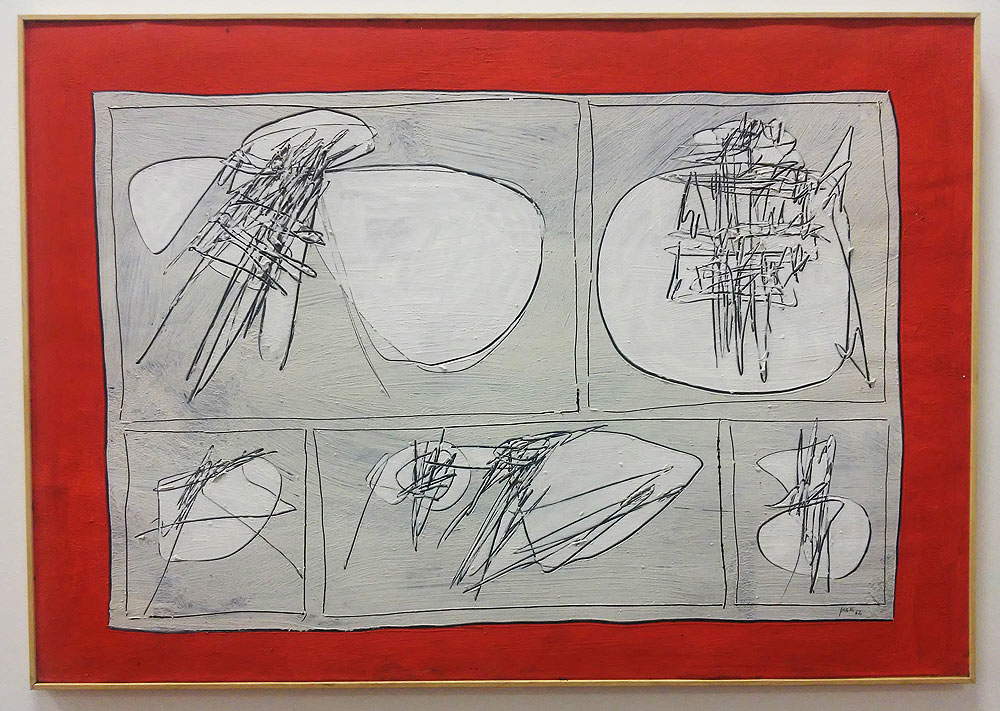

| Achille Perilli, Studio (1962; mixed media on cardboard, 70 x 100 cm; La Spezia, CAMeC - Modern and Contemporary Art Center) |

|

| Achille Perilli, Studio, detail |

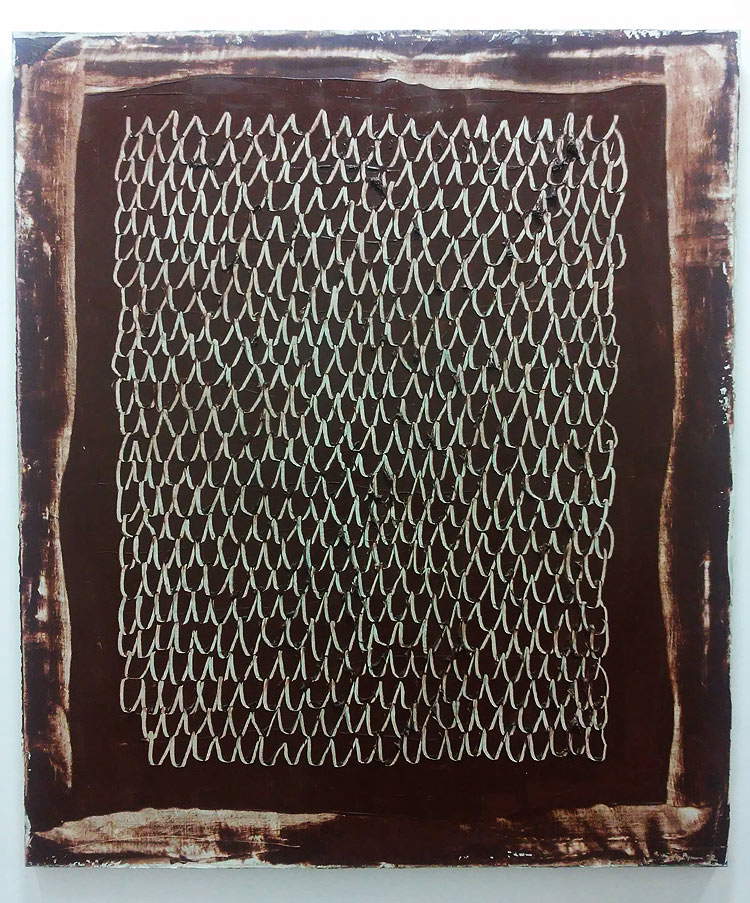

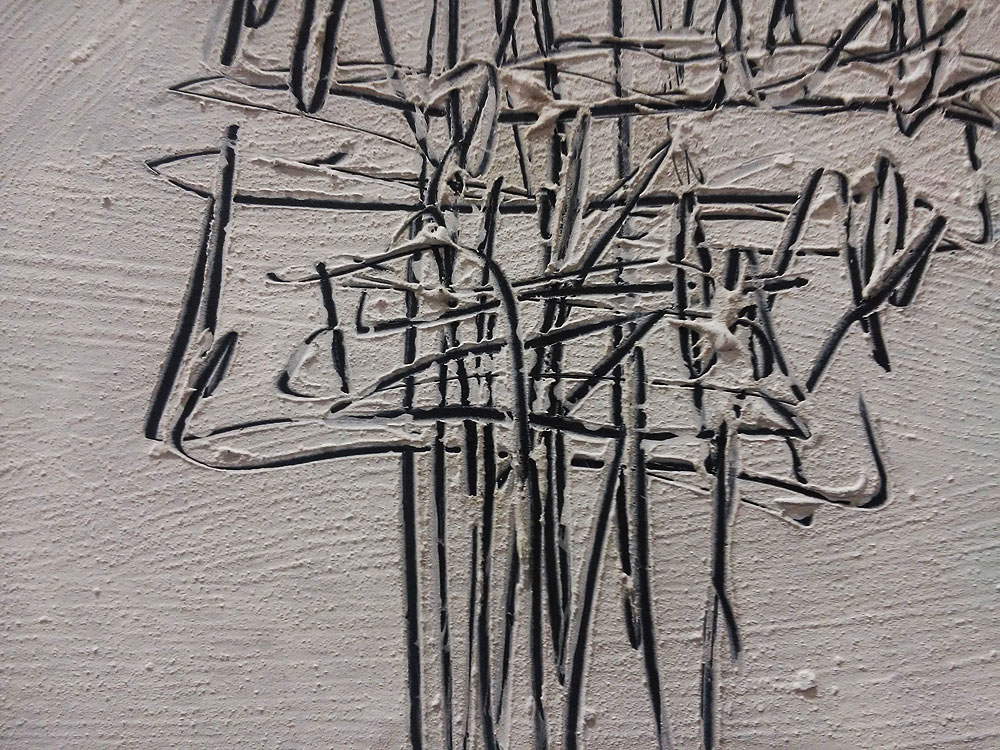

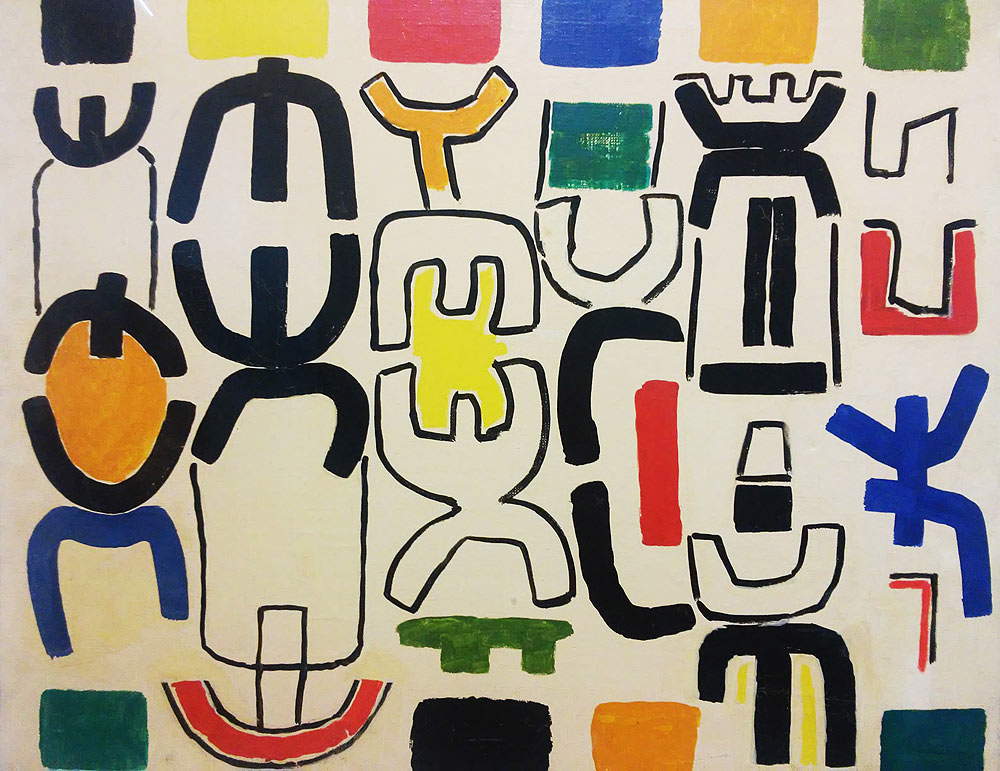

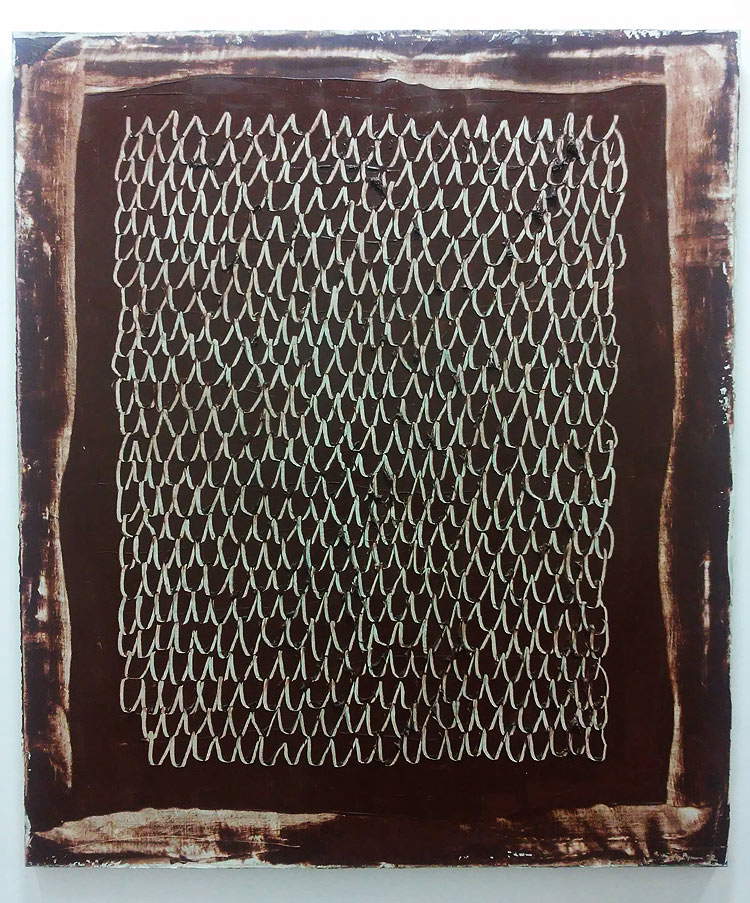

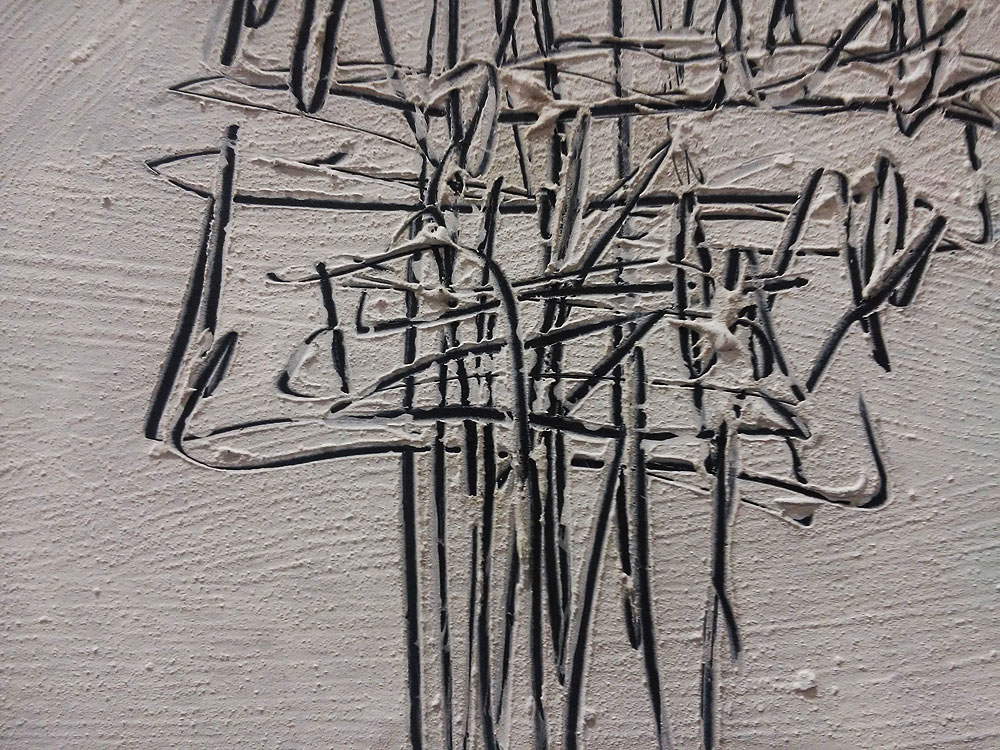

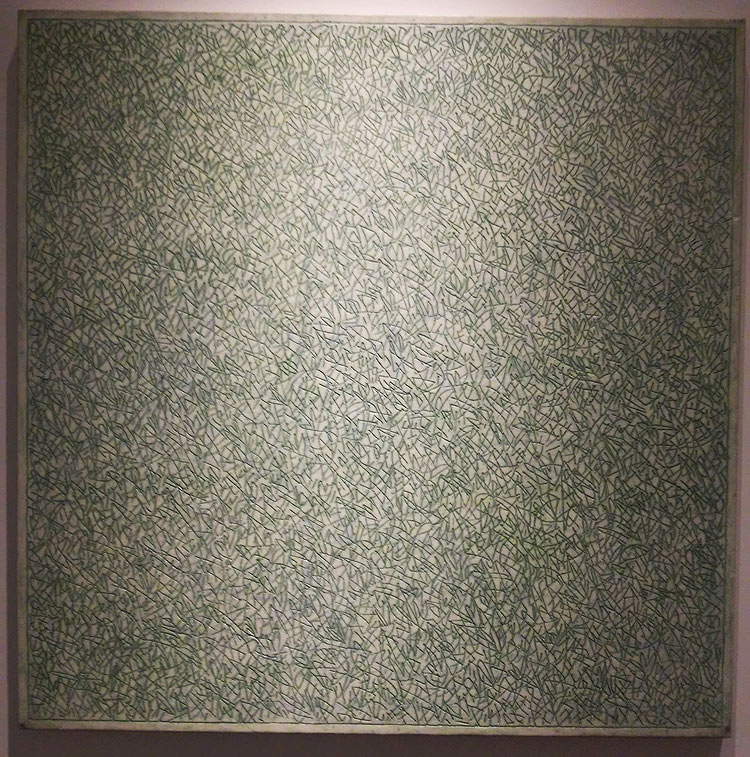

Concluding the itinerary are the works of Sergi Barnils, the youngest of the four artists that CAMeC presents to its public. For Barnils, a believing painter, inspiration comes directly from the divinity, the source of artistic creation (just as it was for Michelangelo). It is difficult to delve into Barnils’ sign-writing apart from this fact, not least because the signs that entangle on his works (particularly significant is the Blanquina cycle, of which the La Spezia exhibition displays some examples) are cloaked in religious meanings. Signs that stand out against white, the symbol of absolute purity, and that refer to the sacred scriptures: a crown, a ladder, man and woman, the tree of the knowledge of good and evil, the triangle of God are some of the elements that populate Barnils’ heavenly city, the result of a personal reading of Johannine texts aimed at interpreting them in a perspective of beatitude and salvation. Symbols concealed within the meshes of a writing that, writes Alberto Fiz, "appears to have been made in a trance, almost as if it wanted to retrace the automatism of the Surrealists,“ and that resembles ”a mantra that restores to the sign its primary, even childlike, freedom, so that art, as Klee maintained, does not limit itself to reproducing visible things but makes them visible.“ Punctual, to make this ”primary and childlike freedom" evident, is the comparison with Blanc i casa di Pijuan.

It is a language that intends to establish a direct relationship with the viewer: for Barnils it is important that the viewer of a painting shares the joy that the painter feels in creating his forms and signs. And his is a painting that knows how to be particularly involving: thanks to his very particular writing that is imbued with spirituality and that, thanks to the use of theencaustic technique, by means of which the canvas becomes a sort of tablet on which the artist scratches and engraves (the recovery of an ancient technique is also aimed at establishing a sort of connection with past civilizations), he proposes to return, as it was for Perilli, to the principle of figuration and writing itself. It is an art that is born ofemotion, as the artist himself remarked, and which feeds on emotion.

|

| Works by Sergi Barnils at the exhibition Sign Alphabet. |

|

| Sergi Barnils, Del verger celeste (2015; encaustic on canvas, 200 x 400 cm; Verona, Private Collection) |

|

| Sergi Barnils, Blanquina (2015; encaustic on canvas, 100 x 100 cm; Milan, Private Collection) |

|

| Sergi Barnils, Blanquina, detail |

|

| Joan Hernández Pijuan, Blanc i casa (2003; oil on canvas, 41 x 27 cm; Milan, Private Collection) |

And it is preciselyemotion that is one of the pivotal concepts of the exhibition Sign Alphabet. And it is not that petty, fake and vulgar emotion that curators short of ideas present as a necessary consequence (to be experienced strictly on command) of yet another pre-packaged exhibition on the usual trite and reassuring artists. It is something much deeper: on the one hand there is the emotion of the artist probing his own awareness, his own rationality and irrationality, his own unconscious, his own freedom. And this emotional component of artistic research has often been underestimated or not considered at all by much of contemporary art, which, with its rituals, its established configurations, its own difficulties in freeing itself from postmodern patterns, has stopped confronting this dimension: the exhibition’s merit is also that of emphasizing this particular aspect of art making. And then there is the emotion of the observer, of the public, with whom the sign artist establishes a strong dialogue, since expressing oneself with the sign also means, to use a happy expression of the curator, “absorbing the self and placing it in relation with the community.”

CAMeC thus returns to offer its audience a cultured exhibition, characterized by a distinctly retrospective look, but which also contains bases for a strongly current reflection. An exhibition that is certainly not easy (fortunately: we are literally surrounded by easy exhibitions, which do not instill doubts, which do not spur the public to develop a reflection), which puts us in front of a path that proves to be a continuous discovery (punctual and fascinating comparisons between the artists: it should be emphasized that these are not four separate exhibitions brought together under a single title, but rather an exhibition that aims to make clear the connections, the cross-references, the points of contact between the four experiences presented), and that invites visitors to become part of that sort of plotless tale traced by Barnils, Capogrossi, Perilli and Pijuan.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools.

We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can

find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.