The debut of Sassetta, elegant painter of the 15th century. What the Massa Marittima exhibition looks like

It is the Maremma’s turn to launch Stefano di Giovanni known as Sassetta, an elegant protagonist of early 15th-century Sienese painting, into the crowded arena of ancient art exhibitions. Never before had a monographic exhibition been devoted to this artist, despite the fact that the earliest reconstructions of his personality and production date back more than a hundred years, and despite the fact that his name excelled in the Siena that was beginning to look to the novelties of the Renaissance. The field on which Sassetta makes his debut is the Museo di San Pietro all’Orto in Massa Marittima, which has waited six years before returning to organize a major exhibition: in 2018 it had been for a more resounding name, that of Ambrogio Lorenzetti, with an exhibition built around the Maestà preserved here. It came, however, from the major exhibition organized in Siena the year before, and the small Massetan review set up shortly after, though highly enjoyable and scientifically beyond reproach, seemed more like a sort of coda to its big sister at Santa Maria della Scala, a way to keep attention alive, a kind of little Maremma best-of . This time the paradigm is different: the public who will go to the Museum of San Pietro all’Orto until mid-July for Il Sassetta e il suo tempo will have the opportunity to visit an exhibition full of interesting novelties.

Two circumstances led to organizing the exhibition in Massa Marittima. The first is linked to a presence: as was the case for the exhibition on Ambrogio Lorenzetti, also in this case the occasion was provided by a work preserved in the collection of the host museum: in this case we are talking about the cusp with Archangel Gabriel, in ancient times part of a polyptych that was later dismembered and from which the Virgin Annunciate also comes, unfortunately absent from the exhibition itinerary, today kept at the Yale University Art Gallery. That is, in that museum that was formed in the late 19th century from the collection of an American art critic, James Jackson Jarves, who was in love with Sienese painting. For him, Sassetta was a painter “mystical, excellent in allegory, capable of demonstrating sincere feelings in painting.” It is hard to doubt his words. The second circumstance is instead linked to the decades-long work of the curator, Alessandro Bagnoli, an official of the Superintendence of Siena and Grosseto from 1980 to 2018, the author of a long reconnaissance of the territory that has made it possible to reconstruct in the exhibition, with great precision, the context in which Sassetta workedto redefine some already known personalities and also to introduce a new one, that of Nastagio di Guasparre, a name that has been recovered precisely on the occasion of this review, a painter who followed, more or less, the same path as Sassetta.

Who, then, was this Sassetta also capable of imposing thought? We could see him as an artist who looked much to the tradition of his city, that of Simone Martini and the Lorenzetti brothers, but who was also open to the new of Gentile da Fabriano, of Masolino, of Masaccio. In the early twentieth century this artist was so popular that he attracted the attentions of Bernard Berenson, Roberto Longhi, John Pope-Hennessy, Enzo Carli, and Robert Langton Douglas, author of a delightful History of the Republic of Siena , which was a great success.having attempted an early, pioneering, concise survey of Sassetta’s art, even before Berenson dedicated to him his extravagant monograph A Sienese painter of the Franciscan Legend, moreover panned by Longhi, and before anyone else approached this painter who dictated tastes in the Siena of his time.

We ignore the reasons for the nickname Sassetta, which appears only in an 18th-century text and is not attested in ancient sources. There is no evidence of links with the small, eponymous village in the Val di Cornia, not far from Massa Marittima. More likely, as Gabriele Fattorini speculates, that the nickname was assigned to it because of a misreading of who knows what documents. It sounded good, however, and was more practical than “Stefano di Giovanni,” so it has stuck to him to this day, and one assumes that no one will peel this label off him. Little is known about his beginnings either: it is reasonable to assume that he was born around 1400, in Cortona, the hometown of his father, who was a cook by trade, and that he must have had a meteoric start to his career if already in 1423, in his early twenties, he had been commissioned to paint a polyptych for the Arte della Lana in Siena, the first basis for any reconstruction of his career. And this is also the starting point of the exhibition, which, however, before introducing what remains of the polyptych, opens with a Madonna of Humility housed in the Museo dell’Opera del Duomo in Siena, believed to be a youthful painting, executed around 1423, yet already capable of revealing Masaccesque tangents, as Paolo Dal Poggetto observed by noting “the large, almost abnormal figure of the Child which is an admirable interpretation of the Child of Masaccio’s Saint Anne Metterza.” Sassetta revises Masaccio’s Herculean Baby Jesus according to his own taste, forged by a continuous, fruitful, modern riding of the waves of the fourteenth-century Sienese school: the result is thus a more delicate Child, just as delicate is the little Madonna holding him, a slender, diaphanous figure hidden under the ample cloak that, as it falls to the ground, describes unrealistic, gothic calligraphy. Next to the Madonna of Humility, here are the remains of the polyptych of the Arte della Lana, the singular detachable altarpiece that Sassetta had painted for the guild of Sienese woolworkers: it was only displayed at liturgical celebrations and festivals, which is why it had to remain stored inside a cupboard when not in use, hence the need to engineer a machine that could be easily disassembled. An ease, however, that probably facilitated dismemberment, at the time the guild was suppressed, and the subsequent dispersal of the fragments, so that the three large panels, the major compartment with the Triumph of the Eucharist and the two side ones with St. Anthony Abbot and St. Thomas Aquinas, did not get there.

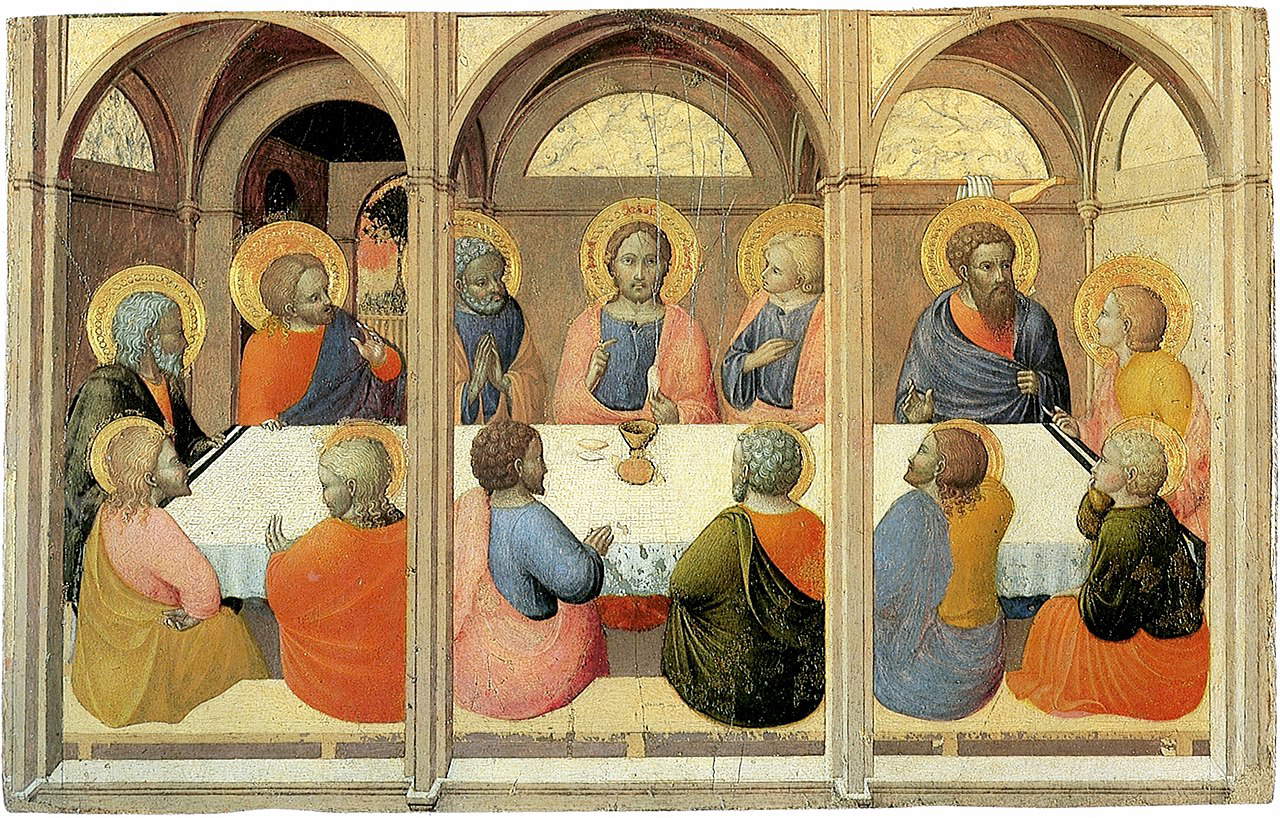

In Massa Marittima, Bagnoli had the twelve fragments usually kept at the Pinacoteca Nazionale in Siena (a museum laudably generous in its loans for this exhibition) arrive, without any reunion with the other surviving fragments, now scattered among Budapest, the Vatican Pinacoteca, Australia, and England. We cannot imagine how Sassetta had painted the panels of the polyptych, but from the saints that adorned the pillars we get the idea of a painter who appears to us immediately capable of supreme finesse (see, in this regard, the accuracy with which the beards of the prophets are painted, or the quality of the motifs of the punches), who stands in continuity with his own tradition but who is nevertheless well disposed to experiment, as the fragment of the predella with theLast Supper shows us, in which Sassetta poses the problem of a credible representation of space. And he reveals himself to be a painter also endowed with discreet narrative gifts: unforgettable is the predella fragment with the scene in which St. Anthony the Abbot is tortured by the devils who rage against him by beating him with clubs and pulling him by his habit. Proof of this taste are the tablets with the mourners from a lost painted cross that Sassetta made for the church of San Martino in Siena (a third fragment, a tablet with St. Martin giving his cloak to the poor man, should be added to the two altarpieces with the Madonna and St. John): the intensity of the Virgin expressing her grief at the loss of her son by weeping hidden in her cloak and with her hands clasped has few other equals in painting of the time. The large St. Anthony the Abbot, with its elongated proportions and light drapery, the remnant of a dismembered polyptych with which a St. Nicholas of Bari now in the Louvre has also been associated, evokes the manner of the coeval Madonna of the Snow of the Uffizi, a masterpiece executed around 1430 and kept in the Uffizi, unfortunately not on display in the exhibition. The list of lenders, it will be noted, does not transcend the boundaries of a narrow area straddling the provinces of Siena and Grosseto, with a few exceptions outside this territory, and all of them in any case included in Tuscany. The exhibition, says the organization, has also been imagined according to principles of “professional ethics,” i.e., giving priority to works in the area and those that can be moved without particular difficulty, and of “sustainability,” which we must imagine first and foremost financial, since we are talking about an exhibition, costing 160,000 euros, built with the forces of a small municipality, as well as two sponsors (Interalia and Toscana Energia) and four patrons (BF spa, Massa Marittima Multiservizi, Patrizio Forci and Fondazione CR Firenze) who supported its commitment: it should be noted, however, that the key presences that have not been made to converge on Massa Marittima are adequately evoked by the paneling in the rooms.

Next to Saint Anthony the Abbot here instead is theArchangel Gabriel around whom the exhibition has been built, and on the adjoining wall theAdoration of the Magi lent by the Chigi Saracini Collection, a small panel that marks the point of maximum approach to Gentile da Fabriano, of whose great Adoration, the one painted in 1423 for Palla Strozzi and now preserved in the Uffizi, Sassetta offers here his personal reinterpretation, according to a’somewhat more prissy elegance and less oriented toward preciousness but capable of surprisingly tasty passages, such as the little dog caught playing with a stick. The next phase of Sassetta’s career, the one that falls between the mid- and late 1930s, is represented by three masterpieces that the visitor encounters in succession: we begin with the Madonna of the Cherries, a panel painting of about 1435 lent by the Archaeological and Art Museum of the Maremma in Grosseto. The Virgin closely recalls that of the Madonna of the Snow in the Uffizi, but updating the model, so to speak, on even softer and more refined lines, with further elongated proportions, a less swampy and more vividness, and with the face of the Madonna taking on those features so personal, so recognizable, with the pointed chin, the high and perfectly curved eyebrow arches, the triangular face, the latter also to be found in the later San Bernardino displayed on the opposite wall. These are the same features to be found in the Madonna and Child from the parish church of San Giovanni Battista at Molli, near Sovicille, on the outskirts of Siena: it is the main novelty of the exhibition, a masterpiece by Sassetta discovered just as the Massa Marittima exhibition was being organized. Cut on all sides, in ancient times perhaps part of a larger work, like the Madonna of the Cherries after all, it was found under a heavy seventeenth-century repainting that had totally obscured it: one detail, the cutting out of the eyes, moved Bagnoli to investigate that heavy two-century-later image more thoroughly, and so, thanks to the work of restorer Barbara Schleicher, the over-painted Madonna was removed and it was thus possible to bring to light the lost Sassetta, a “manifesto,” as Bagnoli himself calls it, of his painting. The iconography is that of the Madonna of Humility, the same one employed for the central panel of the Cortona polyptych, the third masterpiece of Sassetta’s full maturity that the public finds in the exhibition. A work from around 1435, on loan from the Museo Diocesano in Cortona, it was formerly the altarpiece for the chapel of St. Nicholas located in the church of San Domenico in Cortona, and is one of Sassetta’s best-documented works, since we also know the name of the commissioner (a Cortona apothecary named Niccolò di Angelo di Cecco del Peccia), as well as one of his best-preserved paintings. The artist’s finesse can also be seen here in the degree of experimentation with the subject matter: the room’s paneling makes us notice “the wings and cloaks of the angels around the Virgin painted in glazes of color on foil and the minute sgraffito decorations, now done sparingly as in the robe of the angel behind the Madonna and now with translucent lacquer glazes over the background gold in the chasuble of Saint Nicholas.” On the formal level, the Cortona polyptych takes up the elegance of the models of the Sienese tradition (to be found especially in the saints flanking the Virgin in the side compartments), updating them, however, according to volumes that open up to Masaccio and inserting the figures in a unified perspective space, another novelty that Sassetta willingly welcomes in his art. The Virgin, too, acquires a new, full humanity: she is no longer, John Pope-Hennessy also noted in his 1939 monograph, the hieratic enthroned Virgin of the Madonna of the Snow, but a Madonna of humility that is both more resigned and more solid.

The late Sassetta, the one from the 1440s to the 1450s of his disappearance, in the impossibility of gathering in Massa Marittima the various pieces of the Borgo San Sepolcro Polyptych, now scattered halfway around the world from Florence to the Louvre, from New York to Moscow, from London to Berlin, is documented through a pair of saints, a St. Bartholomew and a St. Francis, once parts of a dismembered polyptych executed for the altar of St. Bartholomew in the church of San Pietro in Castelvecchio in Siena: Sassetta’s figures, in the last phase of his career, gain a new, unprecedented solidity, a plastic relief that measures up to Renaissance art already underway, a yet unexplored monumentality, which retains, yes, some late Gothic elements (the drapery of St. Bartholomew is something close, for example, to the sculptures of Lorenzo Ghiberti), but which seems already set out to investigate roads not yet traveled: Sassetta disappeared too soon, however, to follow them over a longer stretch.

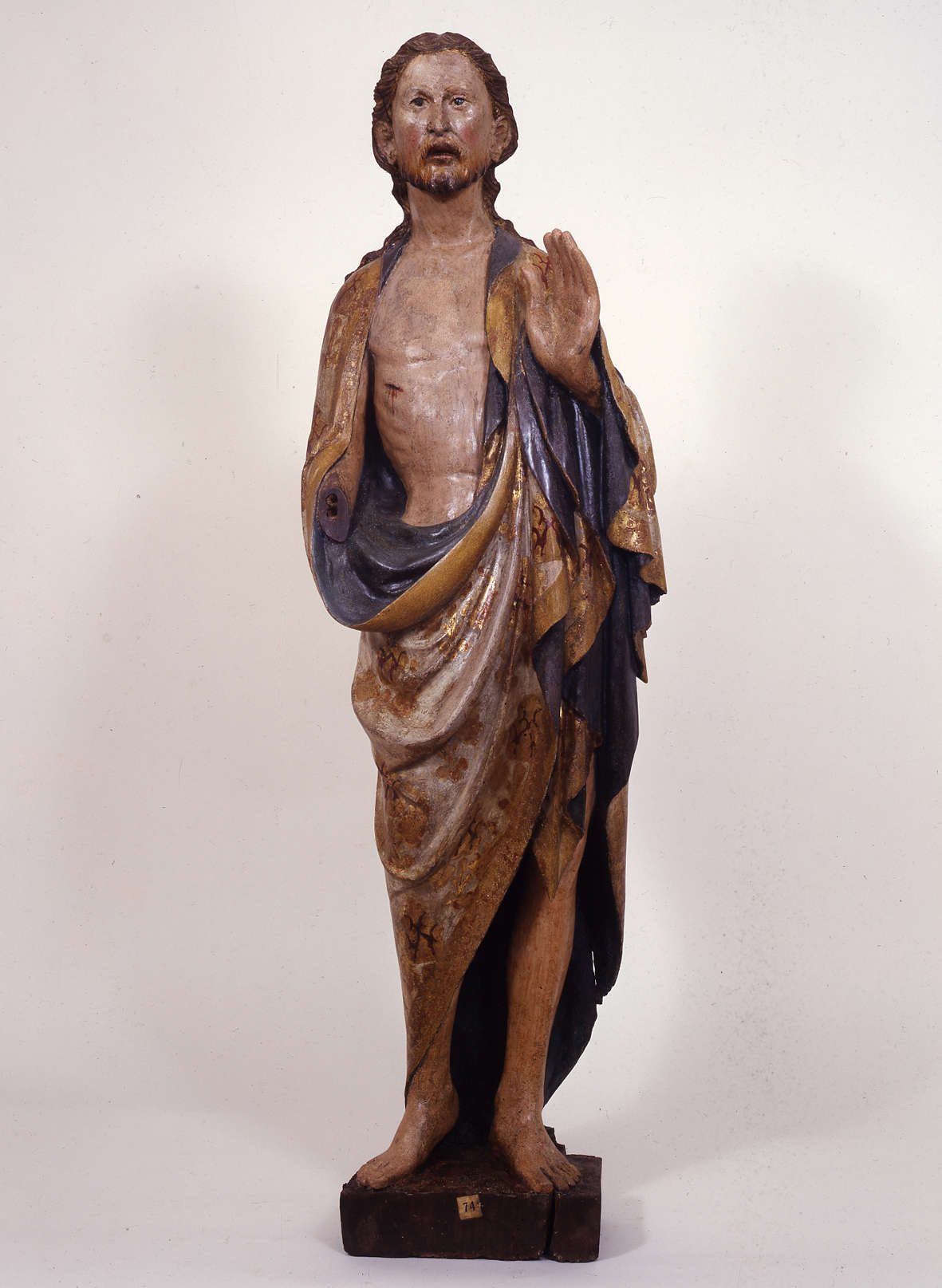

Alongside his works, the end of the exhibition, arranged in two different rooms, introduces the public to the context of Siena between the 1530s and 1550s, with images of artists, especially those from Siena, documenting the high level of the city’s art school, and above all allowing for a deeper understanding, declares Bagnoli in his introduction in the catalog, “of the same lines of interest followed by Sassetta and necessarily comparing themselves with his admirable and conditioning example.” Among the most interesting pieces is anAssumption of the Virgin, complete with a flying girdle left to St. Thomas, an interesting panel by Sano di Pietro, who collaborated with Sassetta (it was he who completed two works left unfinished by his colleague, including the St. Francis on display in the exhibition), and then again a Lamentation on the Deposed Christ, with a Nordic fragrance, by the Master of theOsservanza whose personality is further investigated in the exhibition, so much so that he is presented here as a high-level collaborator of Sano di Pietro in his workshop: and if Sano and the Maestro dell’ Osservanza can be considered two painters close to Sassetta, if not even complementary to him, the exhibition also presents one of his antagonists, namely the more long-lived Giovanni di Paolo (he disappeared in 1482 at the age of eighty-four), a painter more harsh and evanescent than the Cortonese, and also less interested in the novelties coming from Florence, and who nevertheless did not fail to compare himself with his colleague. Then there are sculptures, such as those by Domenico di Niccolò “of the choirs,” a specialist in wooden statuary, an artist who imagined his figures inspired by Sassetta, as Roberto Longhi already noted and as can be verified in the exhibition by comparing his candle-bearing angels or his Saint Francis with the figures of Stefano di Giovanni. Finally, another novelty of the exhibition, is the recovery of a personality to whom a name had not been given until now: this is Nastagio di Guasparre, a painter documented by the sources but never tracked down until now, whom Bagnoli proposes to identify with the works of the artist whom critics, starting with Miklós Boskovits in 1983, had called the “Master of Saint Ansano.” Nastagio, Bagnoli writes, “recovers an important role as a co-protagonist of late Gothic painting in Siena, who follows the cultural path dear to Sassetta, collaborates with the latter and also knows how to take into account what Sano di Pietro and Lorenzo di Pietro known as il Vecchietta were producing.” his are, in the exhibition, a Madonna and Child with Saints granted by the Castle of Gallico, a stained-glass window from the church of San Sebastiano in Chiusdino and now in the town’s Museo Civico, and a Madonna in Humility with Child and Angels.

For Alessandro Bagnoli, who was moreover one of the curators of the major Siena exhibition on Ambrogio Lorenzetti, there is no doubt: the curator has repeatedly defined Sassetta as the most important Sienese painter of the late Gothic season, even going so far as to assign him a leading role, as he writes in the exhibition catalog, “in the last vital season of the Gothic style,” as an artist capable of “recover the lesson of the great Sienese innovators of the early 14th century, innervating it with a personal narrative imagination, combined with the modern tendencies of elegance and extreme decorativism proper to the time and welcoming the novelties of the very modern artistic manifestations of the early Florentine Renaissance.” Comparison with Sassetta’s majors must be imagined, however, since the works of the precursors do not appear in the exhibition, nor do we get to see works by that Gentile da Fabriano who was also an inescapable point of reference for Stefano di Giovanni.

And yet, there are no shortcomings, in the first place because one must take into account the context in which this excellent exhibition was born: it has been said that the Museo di San Pietro all’Orto in Massa Marittima has based its action on criteria of economic sustainability, which is why, moreover, even its programming cannot support every year exhibitions of appeal. The issue is, if anything, a cultural one, and it does not only concern Massa Marittima, but is much broader: between rising insurance and transportation costs, the practice of loan fees often applied blindly, and the difficulty in finding private sponsors, how could one facilitate a museum in a small municipality that would also have the space and intellectual resources to plan a larger exhibition? And then, there is to consider that the stated goal right from the subtitle is to offer a “glimpse” of the Sienese Quattrocento. And the Sassetta exhibition succeeds well, with an intelligent and lively reconstruction, in looking at what happened in early 15th-century Siena through the lens of one of the most fascinating artists who saw the dawn of the Renaissance.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.