by Federico Giannini (Instagram: @federicogiannini1), published on 21/12/2017

Categories: Exhibition reviews

/ Disclaimer

Review of the exhibition 'The City of the Lantern. The iconography of Genoa and its lighthouse between the Middle Ages and the present' in Genoa, Palazzo Reale

Retracing eight centuries of Genoa ’s history through the images of its best-known symbol, the Lantern, in an exhibition that the city is dedicating for the first time to the celebrated lighthouse, the tallest in the entire Mediterranean: this is, broadly speaking, the main objective of The City of the Lantern. The Iconography of Genoa and its Lighthouse between the Middle Ages and the Present, the exhibition curated by Serena Bertolucci and Luca Leoncini that the public can visit until February 4, 2018 in the spaces of the Falcone Theater of the Royal Palace. An iconographic review to suggest to the visitor how much the Lantern ’s profile has contributed (and substantially) to the imagination about the city, and how it has become an element that unites all Genoese as a symbol of belonging. A value that the Lantern has secured ever since it was in fact considered a distinctive sign of the city in the first known topographical maps: the first maps were reproductions of the port, and the most immediate way to recognize Genoa was to offer a clear representation of the lighthouse that welcomed ships at the entrance to the natural amphitheater on which the city stands, and which also served to communicate with the inhabitants.

The main special feature of the exhibition is that it is an exhibition designed for a very wide audience. There are many types of objects that the visitor can find along the route, which is marked in chronological order, with some rooms devoted to in-depth studies of the great painters who dedicated splendid views to the city (and it is almost possible to say that there is no view of Genoa without the Lantern): from paintings to archival documents, from engravings to ancient maps, all the way to advertising posters, lithographs, photographs, postcards, the obvious models of the Lantern, and real curiosities that make up a sort of Wunderkammer, moreover unpublished, all dedicated to the symbol of Genoa (luggage labels, tissue wrapping oranges, soccer players’ jerseys, and much more). It should be emphasized that the Lantern, as well known as it is, has never been an official symbol of Genoa, a role that has instead been filled by other signs such as the griffon, the shield of St. George (or St. George himself, whose figure stands out on the municipal banner), and the Madonna Queen of Genoa: it became so because of its superb size, its recognizability, and its enormous importance for the city. These are all characteristics that have been acknowledged to her by artists, painters, topographers, and rulers (many doges wanted the Lantern to appear in their official portraits) at least since 1371, the year to which the first known depiction of the Genoese lighthouse dates.

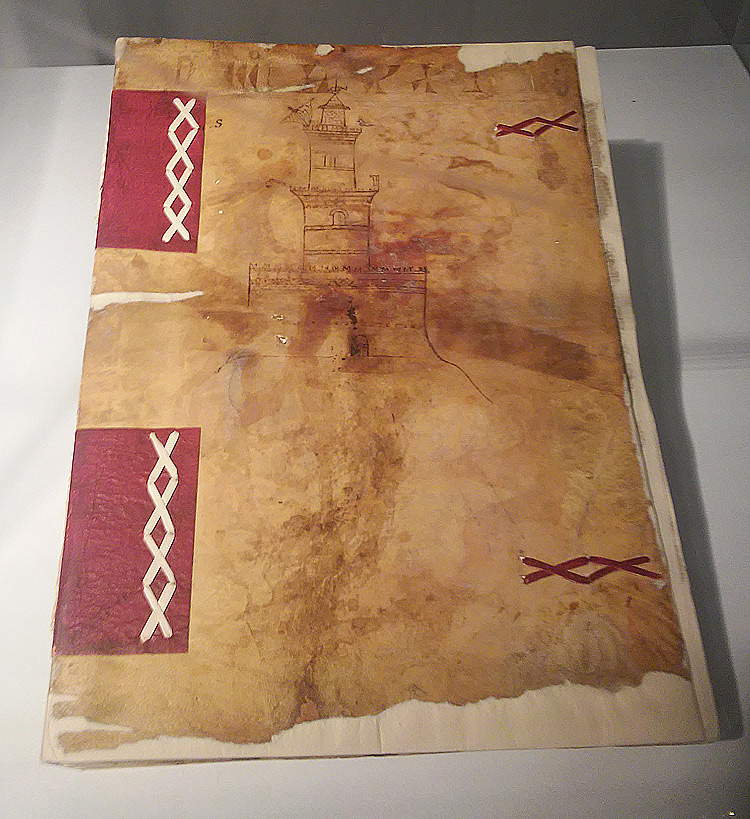

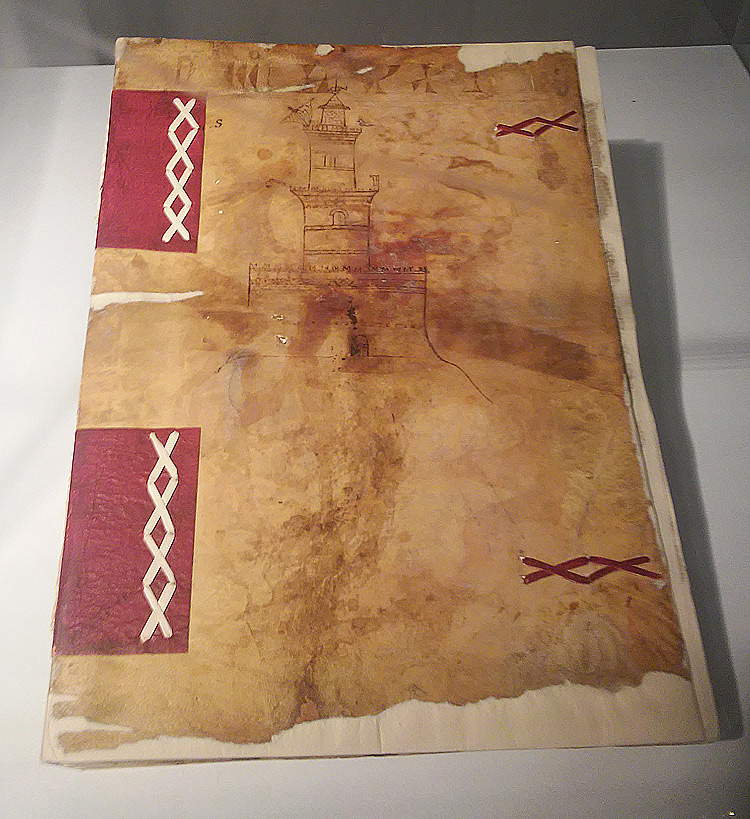

Its history, however, is definitely older: tradition dates the construction of the Lantern to 1128, although the building probably has origins to be sought even further back in time. The depiction mentioned above can be found on the parchment cover of a register of accounts of the Salvatori del porto e del molo, the entity to which, at the time, was entrusted the management of Genoa’s seaport: in the volume were noted revenues and expenditures related to the operation of the lighthouse (these were mainly expenses for fuel and for the personnel assigned to the maintenance of the structure). This is a document of fundamental importance for understanding what the Lanterna looked like in ancient times, that is, before it was totally rebuilt in its present form in 1543, some time after the events that led Genoa to free itself from the French domination to which it was subject and to abandon the form of government of the compagna communis to give itself the structure of a Republic. The state had been subject to French rule since 1499: following a revolt that ended badly, the French decided to build a fortress (the Briglia) in 1507 on the promontory of Capo di Faro, right where the Lanterna stood. The castle came into being with the aim of discouraging new attempts at insurrection, but it achieved little result since, just six years later, the inhabitants, led by Emanuele Cavallo and Andrea Doria, laid siege to the fortress to drive out the French: they succeeded and the Briglia was destroyed, but the Lanterna suffered extensive damage, so much so that thirty years later it had to be rebuilt. By contrast, the older Lanterna is more squat in shape than the present building, which instead appears more slender (it reaches seventy-seven meters in height, although the earlier lighthouse was also particularly tall), and in the depiction on the cover of the register it appears with many of the instruments that were used to send communications to the city (in ancient times, in fact, the Lanterna also served as a watchtower and guard tower): the pole with illuminated lanterns indicated how many ships were entering the city, the sail hoisted on top served as an indicator during daylight hours, the bird on the opposite side is a carrier pigeon, while on the highest point the fish is simply a Christian symbol. Moreover, the cover has recently been restored, with an intervention, designed by Giustina Olgiati, rather difficult given the poor state of preservation of the object, which has suffered several damages over time (tears, lacerations, even the dripping of a liquid).

|

| The City of the Lantern. The iconography of Genoa and its lighthouse between the Middle Ages and the present. |

|

| A room of the exhibition |

|

| Model of the Lantern of Genoa |

|

| Cover of the Register of Accounts of the Saviors of the Port and Pier (1371; ink on parchment, 40 x 30 cm; Genoa, State Archives) |

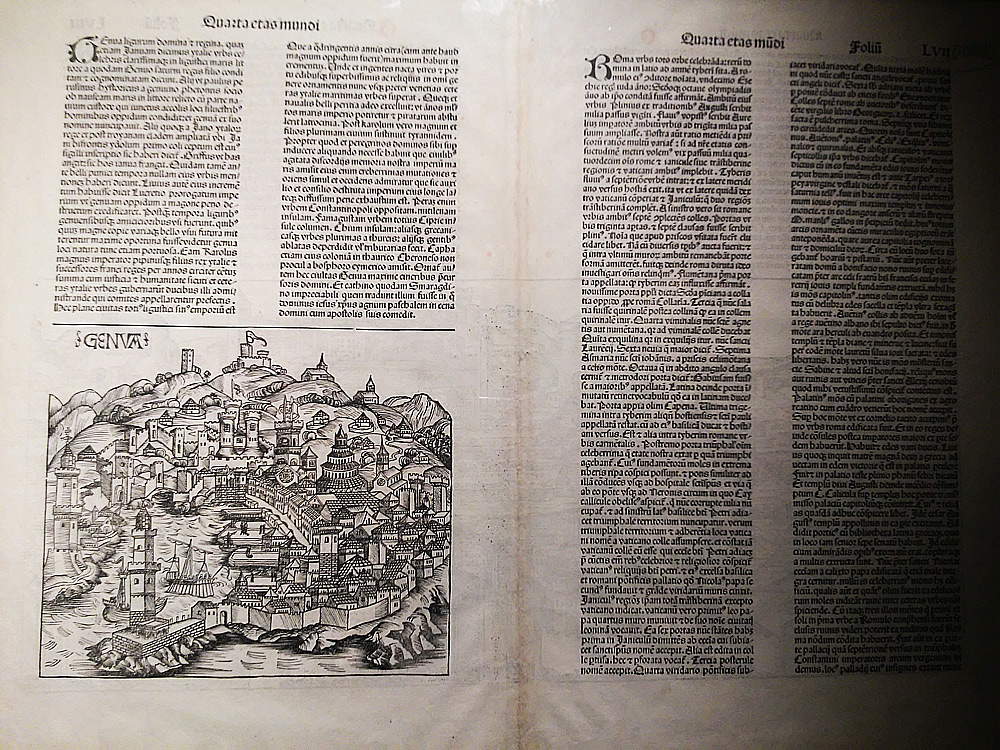

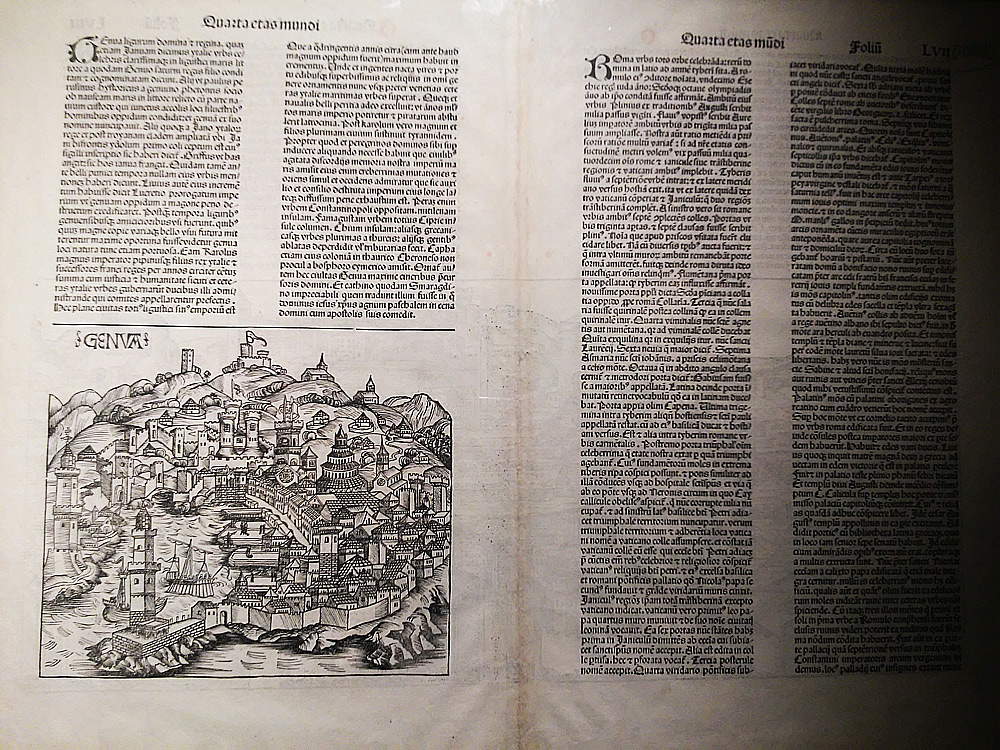

The first aisle of the exhibition displays a long series of woodcuts and antique prints that show us the historical evolution of Genoa and the lighthouse from the 15th century onward. Among the oldest images of the city is a woodcut by the German painter Michael Wolgemuth (Nuremberg, 1434 - 1519), made in 1493 as an illustration for the Liber Chronicarum by Hartmann Schedel (Nuremberg, 1440 - 1514), a book that contained the history of several cities, many of which were depicted with great accuracy for the first time: the image of Genoa, among the oldest known images of the city, reveals great accuracy, which even today allows us to recognize many monuments, from the Lanterna itself to the Cathedral of San Lorenzo, from the porticos of Ripa to the Torre dei Greci (the tower that towered over the mouth of the harbor opposite the lighthouse), from the gateways that still exist today to Castelletto, the fort that dominated Genoa and was demolished in the nineteenth century. The engraving makes us fully aware that already at that time Genoa was a large city, stretching from one end of its harbor to the other: a figuration that, as Cesare De Seta wrote as early as 1985, “has acquired an articulation quite different from the syncretic one of nautical maps: it is an object whose main elements of identity are known and they are arranged with order, even with detail, within the now familiar lines of the bay and the restrictive mountains.” Indeed, it is necessary to emphasize how the works illustrating the city tend, with the advance of time, to become more and more faithful and to free themselves from the logic of mere utility covered by the depictions that were encountered on nautical charts: the authors begin to depict the mountains behind the city, to provide precise images of the churches and the main city buildings, the port is described more accurately. This is how we arrive at a work as important as the etching, by an anonymous author, La tres celebre cité de Gennes, of 1571: here the depiction extends from Sampierdarena to the Bisagno, the considerable traffic of vessels in the roadstead offers the image of an active and flourishing port, and the names of some of the main monuments are also included.

Observing the prints depicting Genoa over the centuries is also tantamount to tracing not only the city’surban evolution (what we see in the Nuova delineatione della nobilissima e famosissima città di Genova of 1651 is a very different Genoa from that of 1571: in between passed the so-called Siglo de los Genoveses, the so-called “century of the Genoese,” which is conventionally placed between 1528 and 1627 and represents the period of maximum splendor of the Republic, ruler of the seas, commercial hub among the first in Europe, banking center of international importance as well as notable artistic and cultural pole), but also its history tout court: interesting is the idea of presenting in the exhibition prints and paintings depicting fundamental events of the historical events of Genoa. Of particular note is a painting by Jan Karel Donatus van Beecq (Amsterdam, 1638 - 1722) depicting a View of the French fleet during the bombardment of Genoa in 1684, when the city suffered the siege and cannonade of the ships of the Sun King eager to break the alliance between the Republic of Genoa and Spain (but the Genoese, despite the thousands of bombs that caused great damage to the city, managed to resist strenuously and repelled the attackers), and the very special pair of paintings by Leopoldina Zanetti Borzino (Venice, 1826 - Milan, 1902), a painter of Venetian origin but long active in the city who dedicated two views to the entry of the French fleet into Genoa in 1859: the Second War of Independence was being fought at the time and France was an ally of the Kingdom of Sardinia, of which Genoa was a part. The two views, one from the basin of the New Pier and the other from the Villa del Principe, depict the moment when Napoleon III arrived in the city by sea with his fleet to take command of the army that would fight against the Austrians.

|

| Michael Wolgemut, Genua (1493; woodcut; Genoa, Private Collection) |

|

| Anonymous of the 16th century, La tres celebre cité de Gennes. 1571 (1571; hand-colored etching; Genoa, Topographic Collection of the Municipality) |

|

| Jan Karel Donatus van Beecq, View of the French fleet during the bombardment of Genoa in 1684 (1685; oil on canvas, 110 x 188 cm; Private Collection) |

|

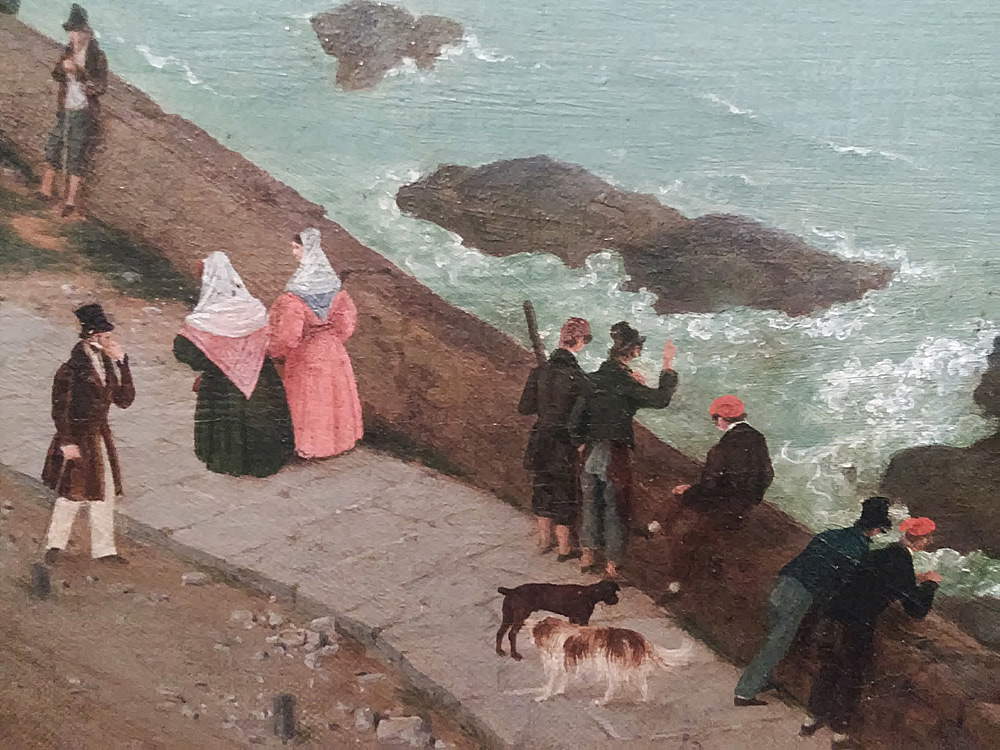

| Leopoldina Zanetti Borzino, French troops disembark in the port of Genoa, view from the Molo Nuovo dock (1859; oil on panel; Genoa, Istituto Mazziniano - Museo del Risorgimento) |

|

| Leopoldina Zanetti Borzino, French troops land in the port of Genoa, view from the Villa del Principe (1859; oil on panel; Genoa, Istituto Mazziniano - Museo del Risorgimento) |

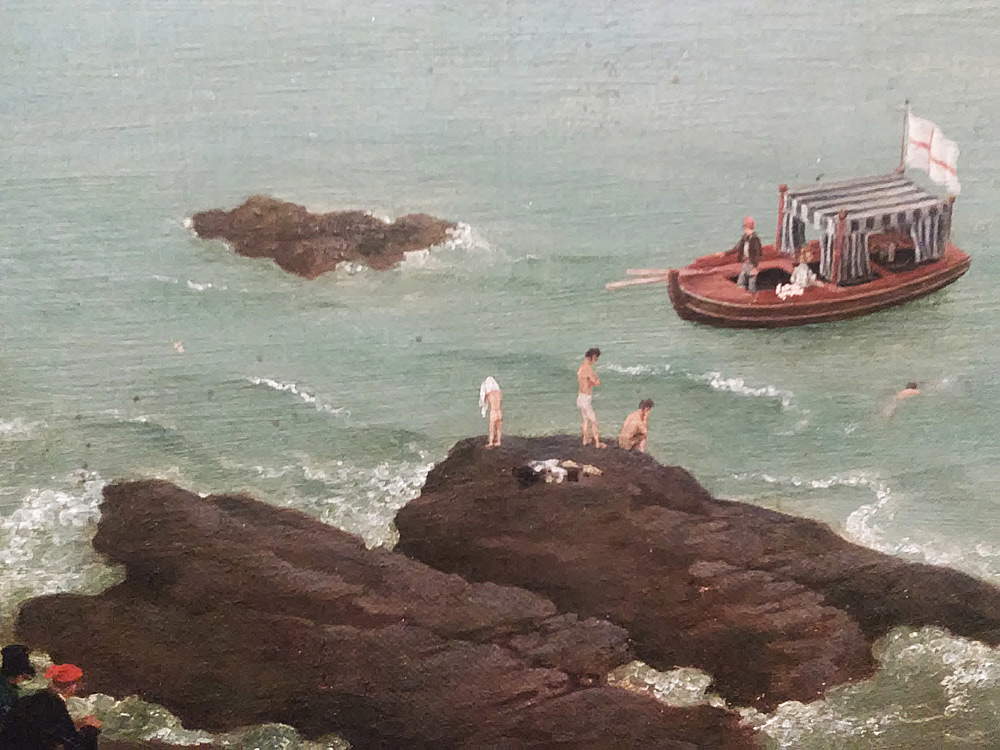

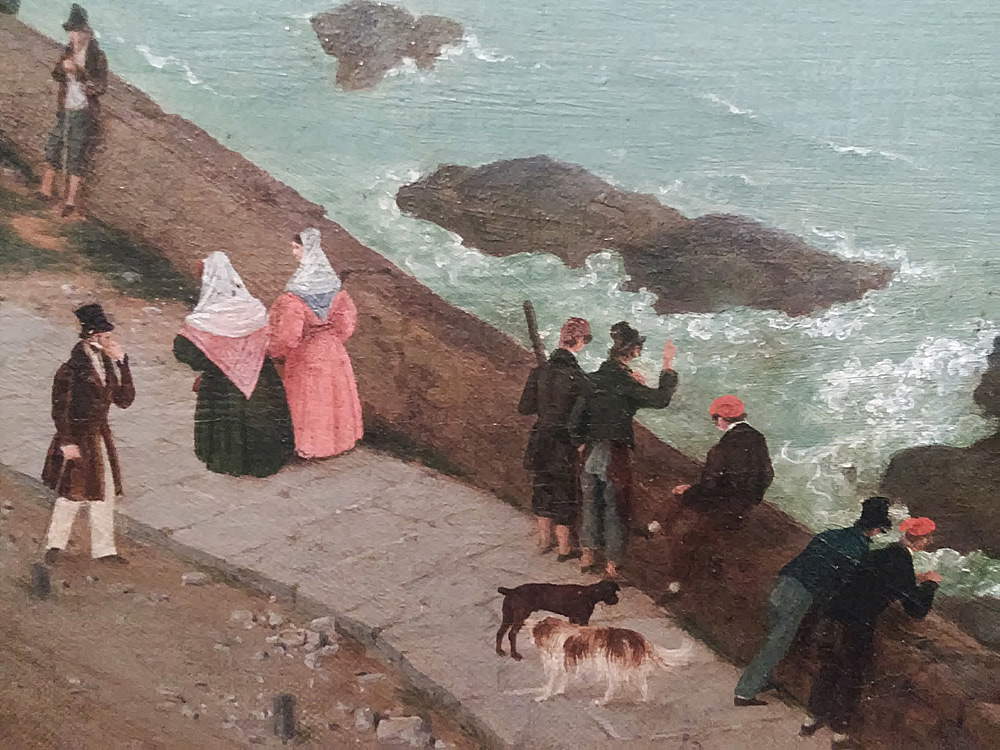

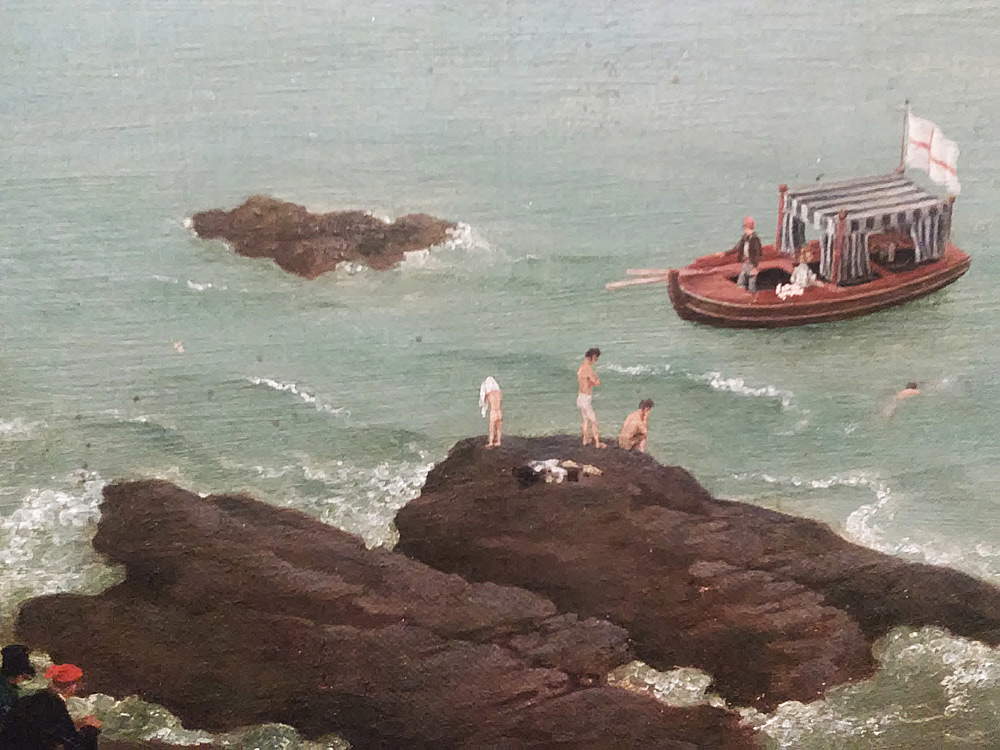

In the rooms that occupy what was once the stalls of the Teatro del Falcone, the visitor finds a careful selection of paintings made by artists who declined in various ways the theme of the view of Genoa, with sections reserved for different painters. We begin with perhaps the most famous name, that of the Venetian Ippolito Caffi (Belluno, 1809 - Lissa, 1866): his views do not aim so much at descriptive precision (although there is no lack of examples in this regard: see the great Panorama of 1849), as at evoking an atmosphere through the skillful use of light and color. One of his cards proposes a view of the harbor from the hills behind it as a storm is brewing: the dark mass of clouds looming on the horizon colors the sea of the harbor basin in a heavy blue that makes the contrast with the portions of water illuminated by the last rays of a sun that will soon be totally covered by rain-laden clouds even more marked. Not dissimilar in intent is Bagno delle donne a Genova, one of the earliest known bathing-themed works: despite the new subject matter, Caffi is more interested in rendering atmospheric effects. Then there is room for a “home-grown” artist, Luigi Garibbo (Genoa, 1782 or 1784 - Florence, 1869), an artist who prefers broad views but also often lingers on details that make his scenes decidedly tasteful, anticipating the nineteenth-century realist landscape: this is the case with a large watercolor, Sampierdarena veduta da san Benigno, from 1820, which offers the viewer a glimpse of life at the time, with a ship flying the U.S. flag about to leave the harbor, some young boys diving from the rocks, noblemen watching the promenade from the terrace of their home with a maid watering flowers, even two small dogs sniffing each other.

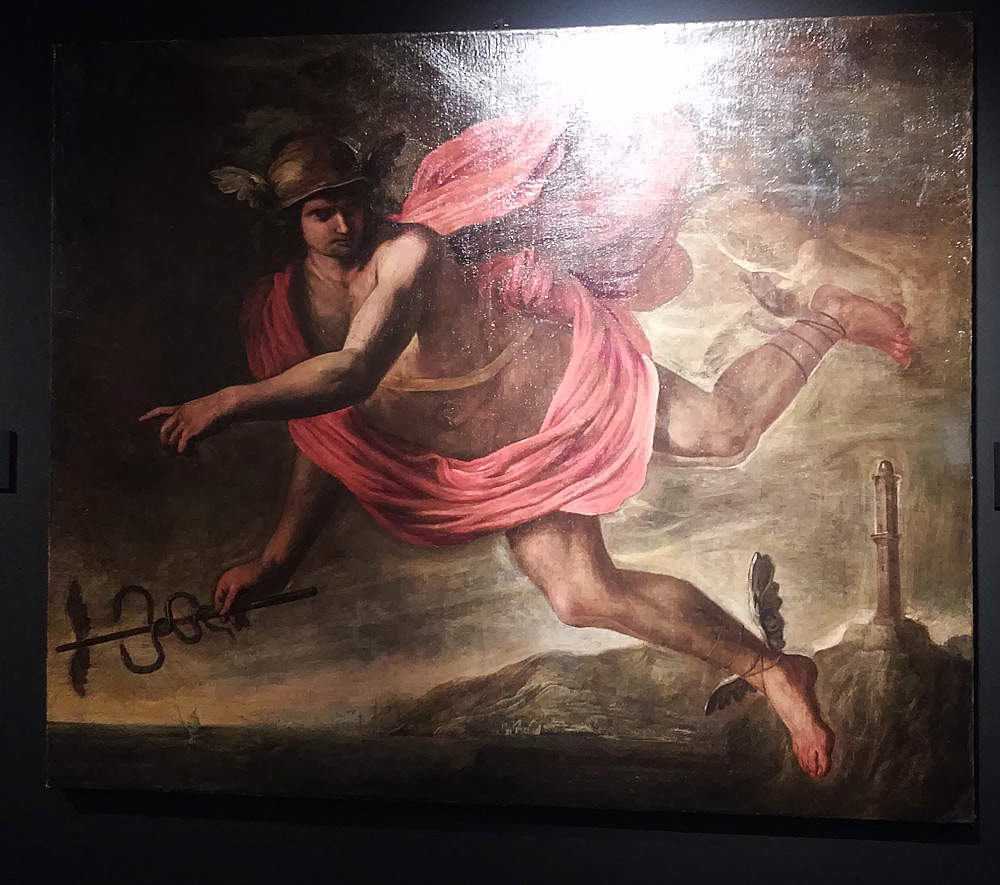

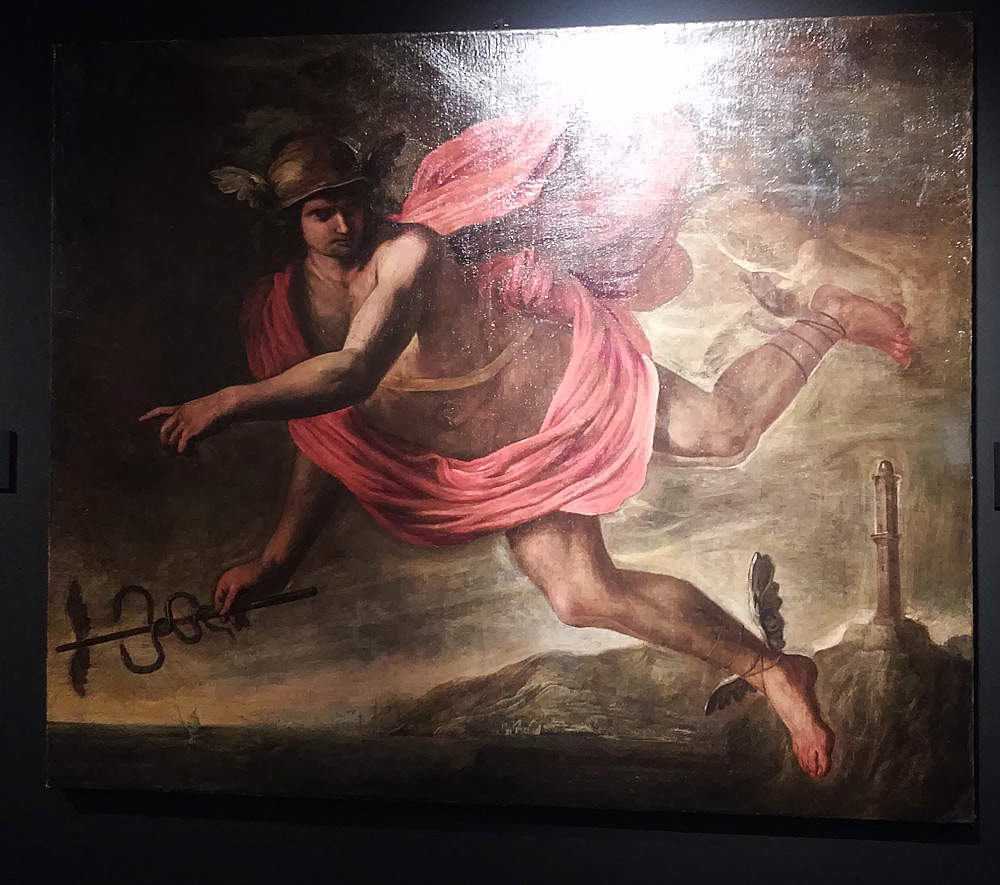

There is also no shortage of particularly curious paintings: sure to catch the visitor’s eye is the diptych by Swiss artist Carlo Bossoli (Davesco-Soragno, 1815-Turin, 1884), which depicts the great Marble Terraces, the sumptuous porticoes that overlooked today’s Piazza Caricamento and were used as a promenade until their demolition (between 1885 and 1886, after just forty years of life), at two times of the day, namely during the day and at night. Among the “stars” of the exhibition at the Royal Palace, it is then impossible not to mention the Panorama of Genoa designed by Henry Parke (London, 1790 - 1835) to be seen from inside a cylinder: that is, the visitor had to place himself in the center of the cylinder in order to have a true illusion of how the city must have looked in reality. Lastly, it is worth mentioning the paintings in which the Lantern rises as a symbol of the city: in the unusual Mercury as Ligurian Genius by Giovanni Battista Carlone (Genoa, 1603 - Parodi Ligure, c. 1684) the lighthouse stands on a promontory much higher than the real one, while in some portraits of the doges in the exhibition itinerary the Lantern becomes a backdrop to be flaunted almost as a symbol of power.

|

| Ippolito Caffi, Genoa. Panorama (1849; oil on two joined boards; Venice, Galleria Internazionale d’Arte Moderna di Ca’ Pesaro) |

|

| Ippolito Caffi, Genoa. With Effect of Storm (1854; oil on cardboard, 16 x 33 cm; Venice, Galleria Internazionale d’Arte Moderna di Ca’ Pesaro) |

|

| Ippolito Caffi, Bath of Women (1851; oil on cardboard, 15 x 26 cm; Venice, Galleria Internazionale d’Arte Moderna di Ca’ Pesaro) |

|

| Luigi Garibbo, Sampierdarena view from San Benigno (1820; watercolor and pencil on squared cardboard; Genoa, Topographic Collection of the City Council) |

|

| Luigi Garibbo, Sampierdarena view from San Benigno. Detail of the promenade |

|

| Luigi Garibbo, Sampierdarena view from San Benigno. Detail of the ship |

|

| Luigi Garibbo, Sampierdarena view from San Benigno. Detail of the rocks |

|

| Luigi Garibbo, Sampierdarena view from San Benigno. Detail of the terrace |

|

| Carlo Bossoli, Le terrazze di marmo (day) and Le terrazze di marmo (night) (both ca. 1850; tempera-colored engraving; Genoa, Private Collection) |

|

| Giovanni Battista Carlone, Mercury as Ligurian Genius (mid-17th century; oil on canvas; Novi Ligure, Ferdinando Soldani Collection) |

The final corridor takes the visitor to the present day. It is a journey through the last two centuries of Genoese history, with a selection of objects that includes nineteenth-century photographs by August Alfred Noack (Dresden, 1833 - Genoa, 1895), precious documents of the transformations Genoa underwent during the industrial revolution, models of the Lantern, advertising posters of hotels, events and manifestations or campaigns to promote tourism, and even postcards, paintings and photographs by contemporary artists, all the way to soccer: the challenge between Genoa’s two main teams is known as the"derby of the Lantern," and the city’s most famous monument is featured in the series of stamps celebrating Sampdoria ’s victory in the 1990-91 Serie A championship, as well as photographed to occupy a large part of the jersey of Mattia Perin, Genoa ’s goalkeeper from 2013 to the present.

With The City of the Lantern, the Lighthouse finds the best way to celebrate its 890th birthday: a wide-ranging (in the present contribution, only a small part of what the visitor can find along the way has been mentioned) and decidedly tasty popularizing exhibition, demonstrating that, in order to speak to a wide audience, it is not necessary to resort to high-sounding names or exhibitions that resemble funfairs more than exhibitions: a level-headed curatorship, an exhibition itinerary capable of not boring the casual visitor, a clear and effective didactic apparatus, and a selection intelligently made and aimed at achieving the objectives of the scientific project with immediacy are sufficient. All characteristics that are not lacking in the Genoese exhibition. An exhibition that, finally, offers the opportunity to reflect on an idea, launched in the spring by Antonio Musarra and Giacomo Montanari, about a museum of the city, set up with all the rigor of the case, that can offer citizens and those who come from outside a path that is able to satisfy the growing interest (certified by the numbers) in Genoa and its history, all within the framework of a system (in fact still to be built, but founded on excellent foundations) that recognizes the city’s enormous potential and allows for a leap forward in the program of enhancing the great artistic and cultural heritage of Genoa.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools.

We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can

find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.