The ceramics of a great artist who did not like ceramics. Fausto Melotti's exhibition in Lucca

Perhaps, in Fausto Melotti’s intentions, an exhibition such as the one the Fondazione Ragghianti in Lucca is dedicating to him this year should never have been held. The project, curated by Ilaria Bernardi, brings to the halls of the San Micheletto complex an exhaustive selection of Fausto Melotti’s ceramics to investigate this long and significant chapter of his production, which kept him employed almost exclusively for at least fifteen years, from the end of World War II to the early 1960s. The exhibition, which is simply titled Fausto Melotti. Ceramics, falls on the 20th anniversary of the publication of the Trentino artist’s General Catalog of Ceramics. And it would be interesting to know what Melotti would have thought of such high attention to his ceramic production, because for him it had been a kind of fallback. An activity in which he believed little, so much so that he almost went so far as to be ashamed of it. In his mind, ceramics was the expedient he had been forced to devote himself to in order to avoid poverty, destitution, to find something with which to live and still leave the door to art ajar. A plan B, we might say.

In one of the rooms of the exhibition, one pauses for about twenty minutes to watch an intense interview from 1984, in which Melotti confided to Antonia Mulas, for the first and only time in his career on that very subject, which he perhaps considered uncomfortable, almost embarrassing. “Since sculpture didn’t give me bread and then I don’t like to go into debt [...] I started making ceramics,” he recalled. “I invented a kind of pottery that was really liked and that gave me money, so I could live quietly [...]. Later, at a certain point, they realized that I was not bad as a sculptor either, and I planted ceramics.” Melotti decided to give himself to ceramics when he realized that his ambition to be recognized by critics was being systematically frustrated. Nonetheless, his relationship with ceramics is precocious: he is only twenty-nine years old when, in 1930, he meets Gio Ponti, then artistic director of the Manifattura Richard Ginori, and begins to collaborate with him by making some small sculptures, even managing to get himself published in Domus and to exhibit that same year at the IV Triennale di Arti Decorative in Monza. The young Melotti, however, cultivated different goals for his career: he wanted to surprise critics and the public with his original, innovative abstract sculptures, which he exhibited for the first time in 1934 in a group show at Galleria Il Milione in Milan, and then replicated the following year, in the same venue, with his first solo exhibition. The hoped-for success, however, did not come: Melotti was ignored by everyone, no one would write a line about those light, geometric works that fused sculpture and architecture, aimed at a new harmony between matter and space. In his interview with Antonia Mulas, the artist attributes this failure to a lack of understanding of his work: “I was alone, in solitude, in silence; there was a conspiracy of silence around what I was doing, and for dozens of years I was alone. All the sculptures I was making in my studio that were there to be seen, no one looked at them. Even critics who happened to come to the studio would turn their heads. Then even giving them away, they didn’t want them.” The time for revenge would then come, many years later. And, to Antonia Mulas, Melotti revealed, with a certain pride, that those who had not given his works a glance at the time would later regret it. There still remained, however, a certain distance towards ceramics.

Even he, in essence, could not free himself from the prejudice that at the time accompanied all ceramic production: the idea that a ceramist was not a sculptor, that he expressed himself with less noble means than those of marble or bronze sculpture, that his work had more to do with decoration than with art. And this in spite of the fact that the most circumspect critics no longer had any reservations about ceramics: suffice it to think of the success achieved by the works of Lucio Fontana, which, with few exceptions (a review by Garibaldo Marussi is often cited when speaking of Fontana’s ceramics, who, on the occasion of one of his exhibitions at the Milione in 1950, wrote, in an almost contemptuous tone, that “the works Fontana presents today are almost all plates, large plates, to be hung on the wall, to enliven the tone of an environment”), always won the favor of the critics. It is well known, however, that self-representation is not the best way to reconstruct an artist’s journey in a timely manner, and if the artist believes that a part of his or her production has little significance, it is not always the case that this is true. This is the case with Fausto Melotti’s ceramics: his continuous and constant search for recognition as an abstract sculptor does not make his work in ceramics any less relevant. With ceramics, Melotti never ceases to experiment, to innovate, to expand the boundaries of sculpture itself, so much so that he transforms everyday objects, such as plates and even tiles, into sculptures capable of conveying to the observer the sense of that “love of fragility and lightness” that Giuliano Briganti attributed to him and that sustains all his work.

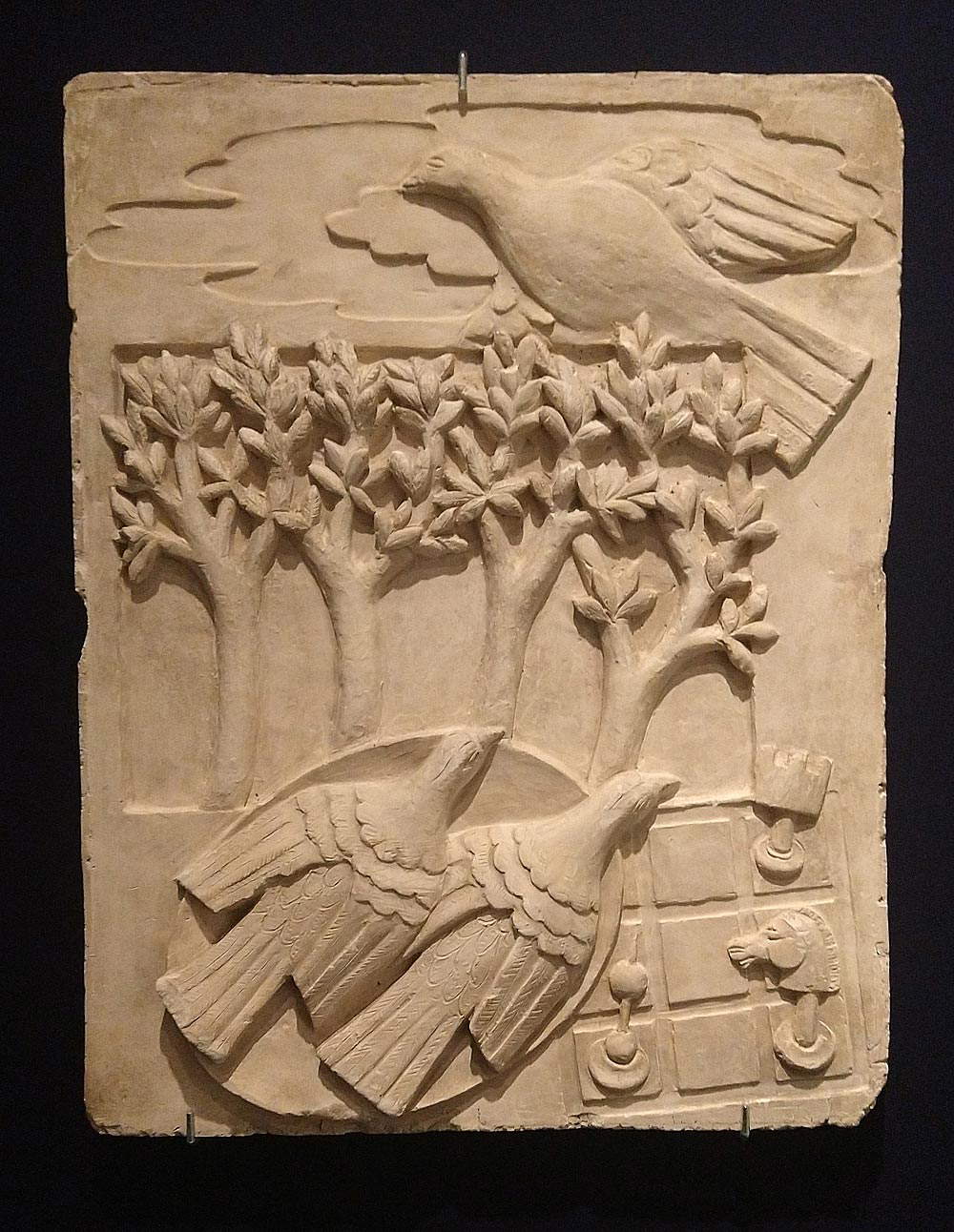

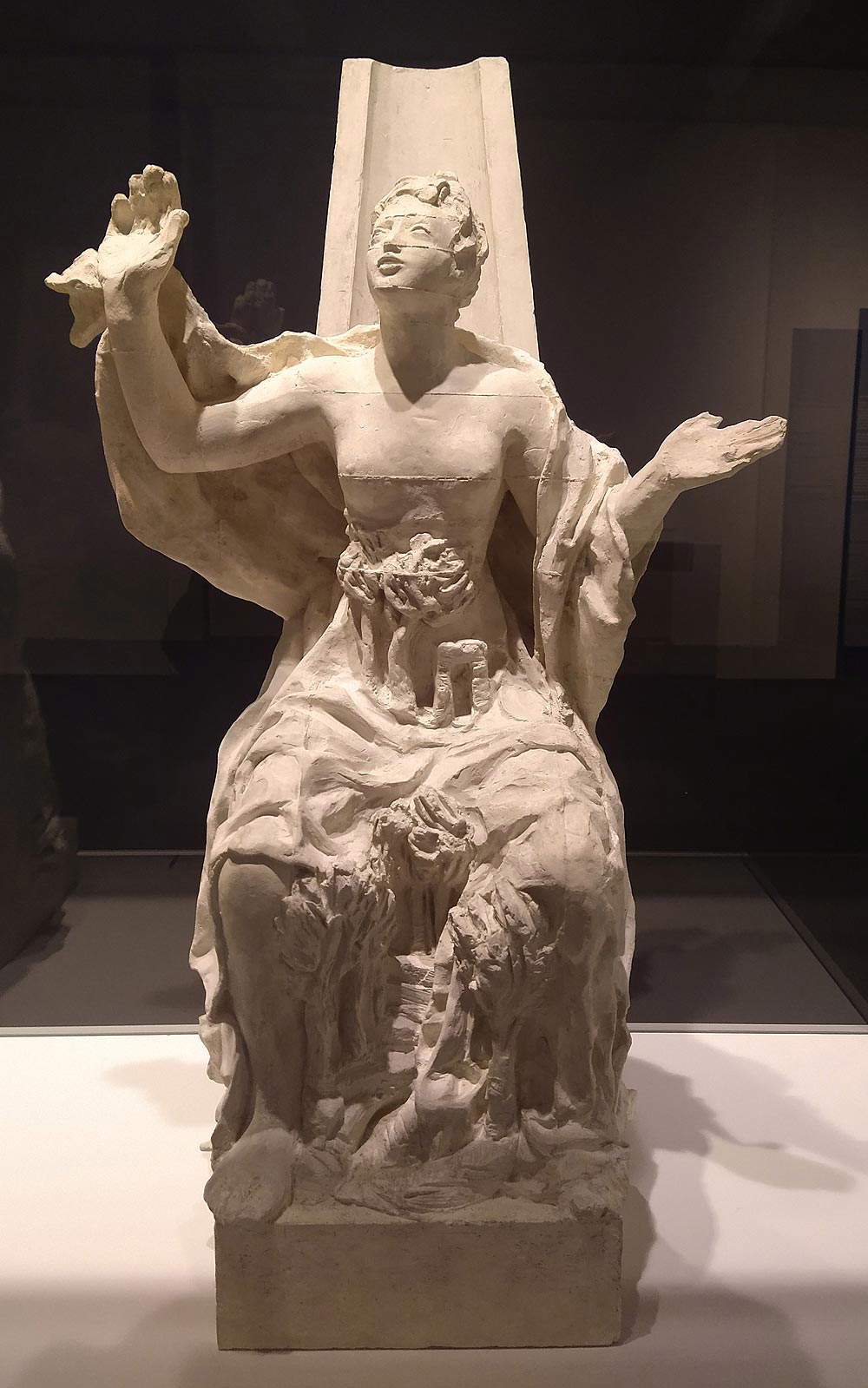

Melotti’s ceramic beginnings are reconstructed in the first section of the exhibition, which displays a sparse nucleus of works from the 1930s, starting with a simple and scholastic plaster bas-relief made by the artist together with his students from the free course in Modern Plastic Art at the School of Furniture in Cantù, and an elegant and delicate Madonna and Child, which succeeds in sublimating the tender embrace between mother and child in a light, persuasive and evocative synthesis, “which already lets emerge,” writes Ilaria Bernardi, “the artist’s predisposition to a semi-abstraction of the connotations of the face and body so much so that the Child seems to be one with the mother’s body.” Also exhibited in the same section are sketches of Decoration, Painting andArchitecture, all in plaster, made for the vestibule of the Palazzo dell’Arte in Milan on the occasion of the VII Triennale: the personifications of the arts, seated on obelisk-shaped thrones, are strong with a robust physical presence, an archaic monumentality, and a solemn synthesis that calls to mind the language of Mario Sironi, animated by a desire to find a seemingly paradoxical meeting point between classical and modern. Melotti responds by unbalancing himself toward De Chirico: his personifications of the arts, with their hieratic appearance, their geometrizing inserts, their volumes that merge with architecture and landscape (between the legs ofArchitecture we see trees sprouting, and on its lap we also see a building: this is what happened also in De Chirico’s Archaeologists of 1927), are oriented toward a metaphysical, imposing, eternal dimension.

The second section, the most substantial of the exhibition, opens with a confrontation between Lucio Fontana and Fausto Melotti, the exhibition’s high point: a crucifix by Fontana, a 1950 work (a glazed terracotta with lustre and gold on loan from the Museo Internazionale delle Ceramiche in Faenza), an extraordinary example of the baroque nature of Fontana’s ceramics, is placed side by side with Fausto Melotti’s Letter to Fontana, a sort of tribute that the sculptor from Trentino addresses to his friend, and which lays the foundations for his future research, since the synthesis of abstraction and figuration that Melotti achieves with this work (a human face set in an evanescent, almost liquid score), made of dense and vibrant matter, will orient much of his later production, also implicitly establishing the artist’s position within the debate on abstraction and figuration that would set Italian art circles on fire a few years later. This is true both for the works that still show an obvious closeness to Fontana (such as the work Untitled of 1949, a kind of large squirrel that exudes life, light, and movement, exactly like Fontana’s ceramics), and for those that instead begin to break away from his friend’s work. The exhibition provides a way to appreciate this estrangement: theArcidiavolo of 1948 is a work that still bears traces of the infatuation with Fontana’s ceramics, but in the elongation of the figure it already contains the germs of that almost geometric synthesis that will lead Melotti to the formal purity of the Korai of the mid-1950s.

According to Melotti, “art does not represent, but transfigures reality into symbols”: this is clearly seen in the sculptures of animals, represented in good numbers at the Ragghianti Foundation exhibition, from the precocious Walrus to the Giraffe, from the Little Horse to the Rooster, exhibited together with Bruno Munari’s very famous Bulldog and Aligi Sassu’s Yellow Horse. They are perhaps among Melotti’s best-known ceramic achievements and “make clear,” writes Ilaria Bernardi in the catalog, “how their author aspires to delineate a dreamlike, semi-abstract world of Calvinian lightness: that of fantasy [....] It is Melotti’s magical universe that emerges more and more clearly in his ceramics: it is the tension toward abstraction and stylization of forms that allows him to transform forms inspired by the existing into art.” The “oneiric” dimension of his art is also well marked in the abstract reliefs, some of which are exhibited in the Lucca show to further demonstrate Melotti’s updating on the artistic trends of his time: gesture and signs chase each other drawing circles and arabesques over smoky, rarefied, transparent chromatic bases. The room ends with a selection of other sculptures with a distinctly experimental character: on the one hand, the Cerchi, witnesses to further research on pure geometric forms combined to achieve refined results of abstract lyricism, and on the other, the Teatrini, examples of a research begun as early as 1944 with which Melotti gives substance to scenes located on the border between interior and exterior, small environments where episodes, events, and encounters outside of time and space take place. “In the Teatrini,” the artist would later declare, “I did not abandon the rigorous idea of counterpoint, but I wanted to create something in a certain figurative sense, but moving it into an abstract metaphysical environment. ”The Teatrini are almost, in essence, the natural continuation of the research on the borderline between abstraction and figuration that Melotti had already begun by approaching Fontana (interestingly, Fontana himself would later start a series of Teatrini).

The last room is devoted to everyday ceramics, objects with which Melotti thoroughly explores the potential of ceramics: in the display cases, the public has the opportunity to admire vases, cups, small cups, coffee cups, and plates that hover between art and design: “as in an alchemic process,” Ilaria Bernardi explains, “Melotti transforms everyday objects into something else that, in the colors (including blue, white, gold) and the material (in which s pess there are glassy fragments), evokes the abyss of the universe”: objects “so simple in form, they seem like fragments of the universe torn apart by the artist and offered to all of us.” And objects that often put functionality in second place to unbalance themselves toward sculpture: see the coffee cups, with their oblong, impractical shape. Still others can be considered works of art in their own right: this is the case of vases, stripped totally of their primary function, to become abstract sculptures that sometimes take on animal or phytomorphic appearances, often losing the typical form of the vase, close to informal poetics, capable of demonstrating the marked sensitivity that Melotti had as much for material as for color.

Fausto Melotti would leave ceramics in the early 1960s, when the coveted recognition as an abstract sculptor would finally arrive: ceramics, in his view, was no longer necessary. And he could once again be a complete master of the creative process: among the reasons he disliked this art form was the degree of unpredictability given by firing. Melotti recognized fire as the true director of all operations, and even if the final result proved to be identical to what he imagined, he still saw in the finished work the corrections left by the fire. It was as if someone had put commas in what he was saying or writing, the artist said. And he couldn’t stand that. The Ragghianti Foundation exhibition succeeds well, however, in showing how Melotti’s self-assessment was too harsh: his path in ceramics was consistent, experimental, new, up-to-date, modern, careful. His ceramics were just as anti-rhetorical as his sculptures made from other materials. Even with his ceramics Melotti taught us, Giuliano Briganti would have said again, “that fragility is our condition and that only by adopting the language of fragility can we touch with our fingertips things that are not fragile.” This is especially true for ceramics, a fragile material in itself. The great critic had the Theaters in mind when he wrote these remarks. He had in mind the ephemeral poetry of the scenes that Melotti organized in his metaphysical spaces, he had in mind the great freedom of its lightness, he had in mind that simplicity that is all contemporary and yet could not but consider a certain classical measure. And perhaps without ceramics all the expressive potential of Melotti’s art would never have emerged.

It should then be considered that Melotti’s ceramic production dates back to a period of extraordinary vivacity for this art in Italy: it is the epoch in which the unrepeatable season of Albissola began, the epoch of the experiments of Fontana, Asger Jorn, Leoncillo, and Emilio Scanavino, the epoch in which Picasso began to work the earth in his atelier in Vallauris, the epoch in which design (with Gio Ponti, Bruno Munari, Ettore Sottsass and others) also began to look insistently at ceramics. It is precisely to Carlo Ludovico Ragghianti that we owe, moreover, one of the first reconnaissance of Italian ceramics, namely the exhibition Handicraft as a fine art in Italy that was held in New York in 1947, and where some of Melotti’s vases were also exhibited. Here it is: his experience was among the most original and significant of this path of rediscovery of ceramics, of which he was among the main protagonists, perhaps without realizing it, or at any rate trying to hide it. And the exhibition at the Ragghianti Foundation has the merit of precisely highlighting the extent and versatility of Melotti’s contribution to Italian ceramics and, through ceramics, to the art of his time.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.