The Byzantines: an exhibition in Naples to tell the story of this civilization

Last Wednesday, December 21, the exhibition Byzantines. Places, Symbols and Communities of a Thousand-Year Empire. The exhibition has been on view since Dec. 21 and will remain so until Feb. 13, subject to probable extensions, and was set up in the MANN’s Salone della Meridiana , which had already hosted the previous exhibition on the Lombards in 2017-2018. It is precisely this exhibition on the Byzantines that seems to be the chronological continuation of the one on the Lombards, highlighting the museum’s desire to enhance a sense of continuity in its cultural offerings. The exhibition was curated by Professor Federico Marazzi of the University of Naples Suor Orsola Benincasa and was realized with the support of the Campania Region, is coordinated by Laura Forte (Head of the Exhibitions Office at MANN) and organized by Villaggio Globale International (which had already collaborated with MANN on the occasion of the Canova exhibition), carried out with the collaboration of the University “Suor Orsola Benincasa,” which participated in the creation of the inclusive paths with high tactile accessibility.

The exhibition aims to provide visitors with a tool to learn about aspects of Byzantine culture and thus to delve into the historical phase following the fall of the Western Roman Empire, with insights into Southern Italy, Greece and in particular Naples, a “Byzantine” city for about six centuries after its conquest by Belisarius in 536 AD. This exhibition is the result of collaborations with numerous institutions, in Italy and especially in Greece, which led to the loan of more than 400 works from 33 Italian and 22 Greek museums, as well as from the Vatican Museums and the Fabbrica di San Pietro. It is precisely from Greece that numerous artifacts come, thanks to an agreement between the MANN and the General Directorate of Museums of the Hellenic Ministry of Culture, which has enabled the loan of works from Athens and especially Thessaloniki, where numerous artifacts never before exhibited, found in the recent works of excavations for the Greek city’s subway, come from. All these finds underscore a strong common cultural tradition between these places and many Italian cities, such as Ravenna and Naples itself, highlighting the cultural complexity of an extremely vast empire: very diverse populations with a common culture.

The exhibition traces the stages of Byzantine civilization from its rise to the complete fall of Constantinople. In 476, Rome and the Western Roman Empire had fallen at the hands of Odoacer: Constantinople, which had already been founded in 330, thus became the “new Rome.” The Empire at that time occupied present-day Turkey and Greece, but also Syria, Jerusalem, Egypt, and part of Libya. Around 565, following numerous wars and the death of Emperor Justinian, Byzantium experienced its greatest expansion through the reconquest of Italy, expansion into North Africa, but also through the conquest of part of Spanish territory. In 730, Byzantine territories suffered a major downsizing at the hands of the Arabs and Lombards, who conquered much of Italy. But 1025 is the year that defines an important consolidation for the Empire, especially in the eastern Mediterranean area, a time when it also established numerous contacts with the Russian world, which would influence its culture. However, after a hundred years, around 1170, the Empire would be downsized again with the loss of territories in Italy and part of Anatolia, before Constantinople itself was taken by the Crusaders and the Venetians in 1204. This downsizing would lead to the collapse of the empire in its final years, before the final seizure of Constantinople in 1453.

The tour at MANN is divided into fifteen sections, consisting of explanatory panels devoted to specific themes and exhibits of all kinds. Each section deals with an aspect of Byzantine civilization: from the relationship with power and the church, to architecture, via trade and the image of the person, with the display of some jewelry. But the exhibition focuses very much above all on the relationship between the empire and the city of Naples, where the MANN is located, seen as a gateway to the Byzantine world, an outpost of the empire on the Mediterranean and the focal point of a dialogue between local Mediterranean cultures, including the Arab culture. Through artifacts and information, the physical presence of places related to Byzantine civilization in Naples is highlighted. Thus, it should be mentioned that several works in the exhibition, including some marble slabs, were found in the city near Piazza Nicola Amore, during the excavations of metro line 1, where several necropolises outside the walls probably stood. The exhibition does not focus solely on the relationship with the city, but expands to the entire region, so much so that in addition to the exhibition catalog (published by Electa), and one dedicated to children, a guide dedicated precisely to Byzantine civilization in Campania will soon be available.

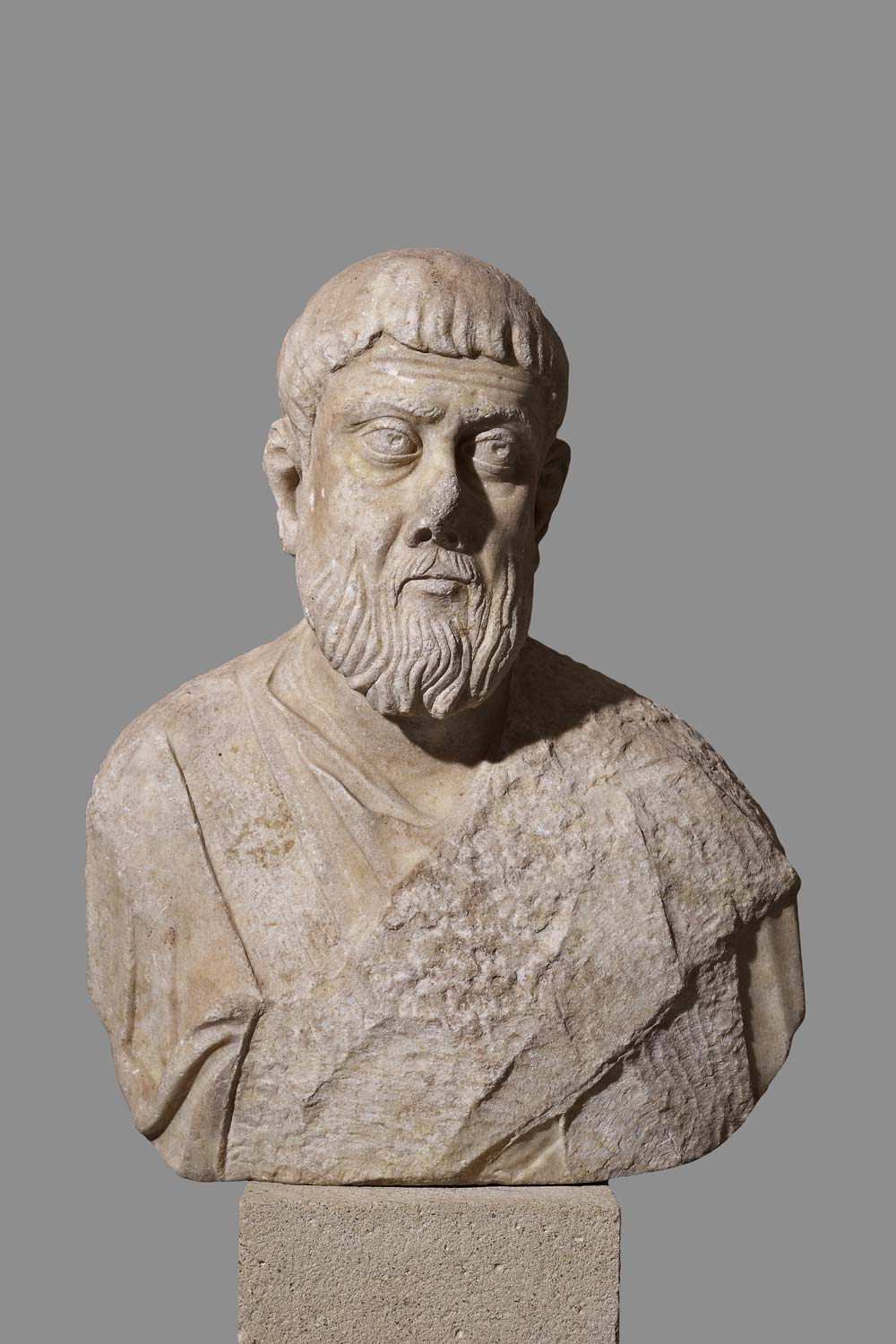

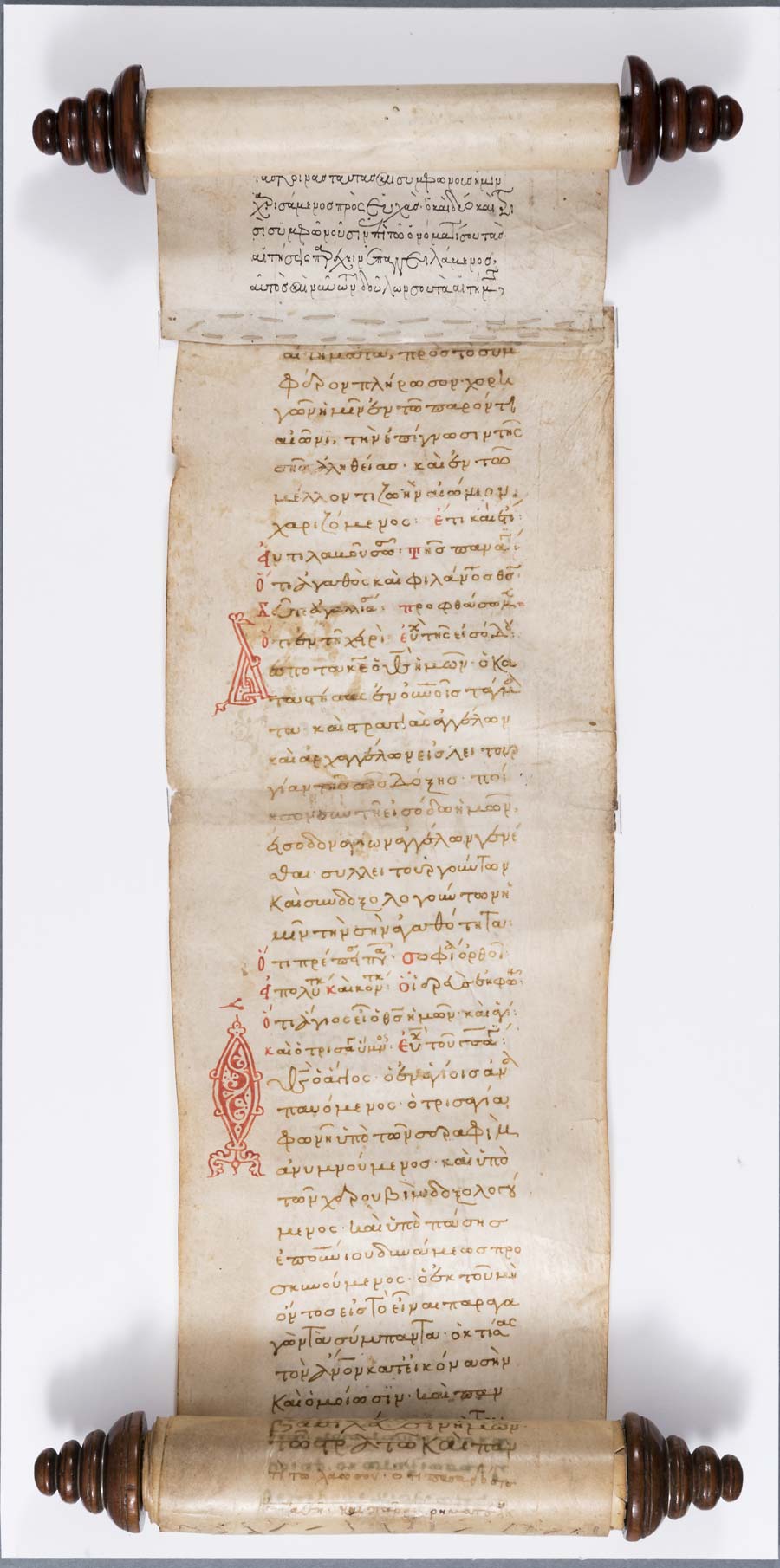

The link between the Byzantine world and the city of Naples is summarized with an exhibited work of great historical and social interest: a coin from around 870, depicting St. Gennaro, the patron saint of Naples, in bishop’s robes. This coin is an important testimony to the strong interest in the cult of St. Gennaro as early as the Byzantine era. The relationship of the empire to the cult and the Church is not only represented to us by the presence of many religious objects, including crosses, reliquaries, icons, stelae and relics. Several artifacts concerning the emperors, including a bronze coin from about 330, and a gold coin from about 530, depicting Constantine I, also highlight how the cult for power itself, in the figure of the emperor, had extremely changed with the influence from the Church: the emperor was no longer an earthly deity, but a man representing one God on earth, in full consistency with the new Christian spirit. The work that best depicts this change in the figure of the emperor is the large lithic plaster slab with the figure of the Emperor (12th-13th century) on loan from the Museo Correr in Venice: here the emperor is represented with the symbols of power, but at the same time the presence of the crucigerous globe in his hand reminds us of the importance of religious value over earthly value. There are also a number of miniatures that are not only religious in subject: in addition to some theological treatises, there are medical texts and epistles, representing an important aspect of this culture, which precisely in these years would have seen a strong development related to monasteries.

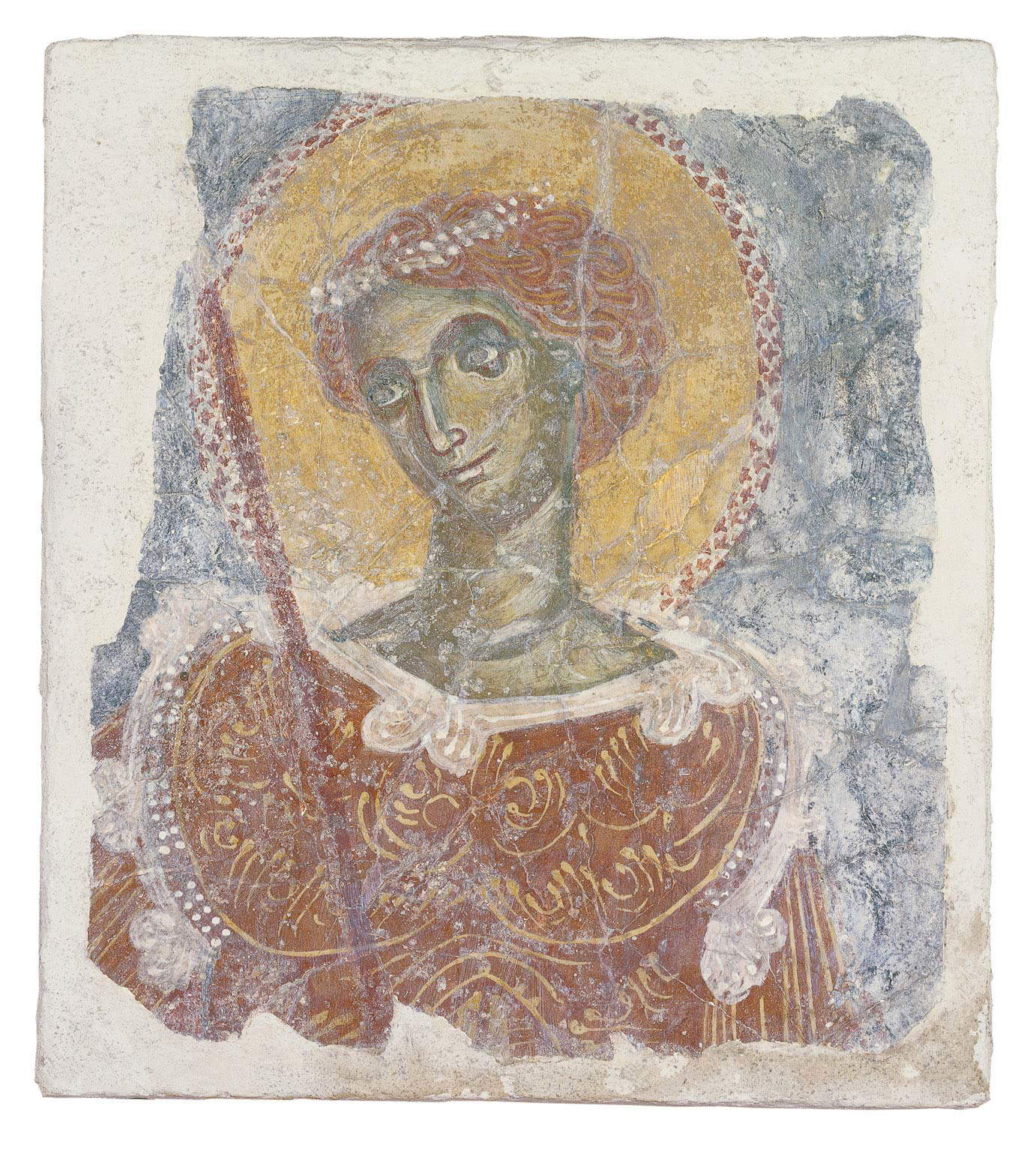

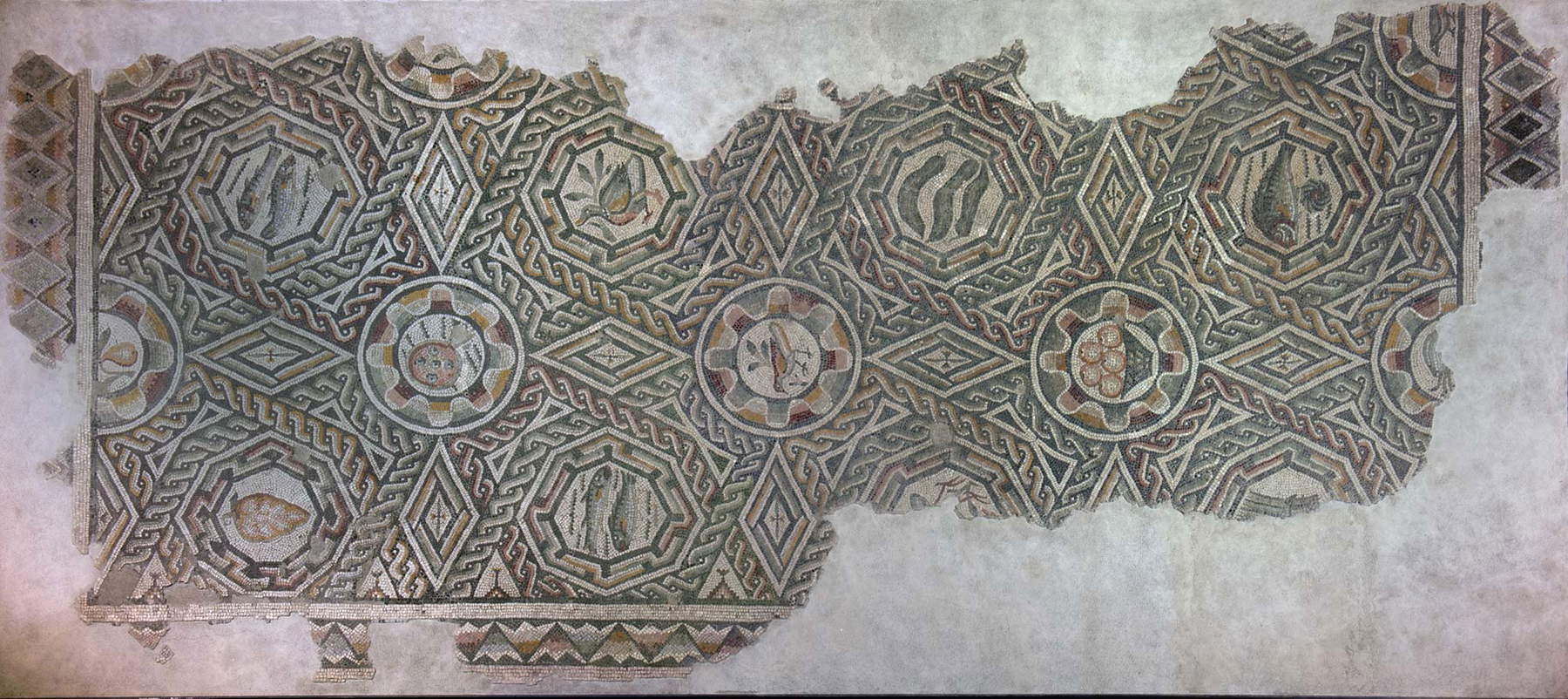

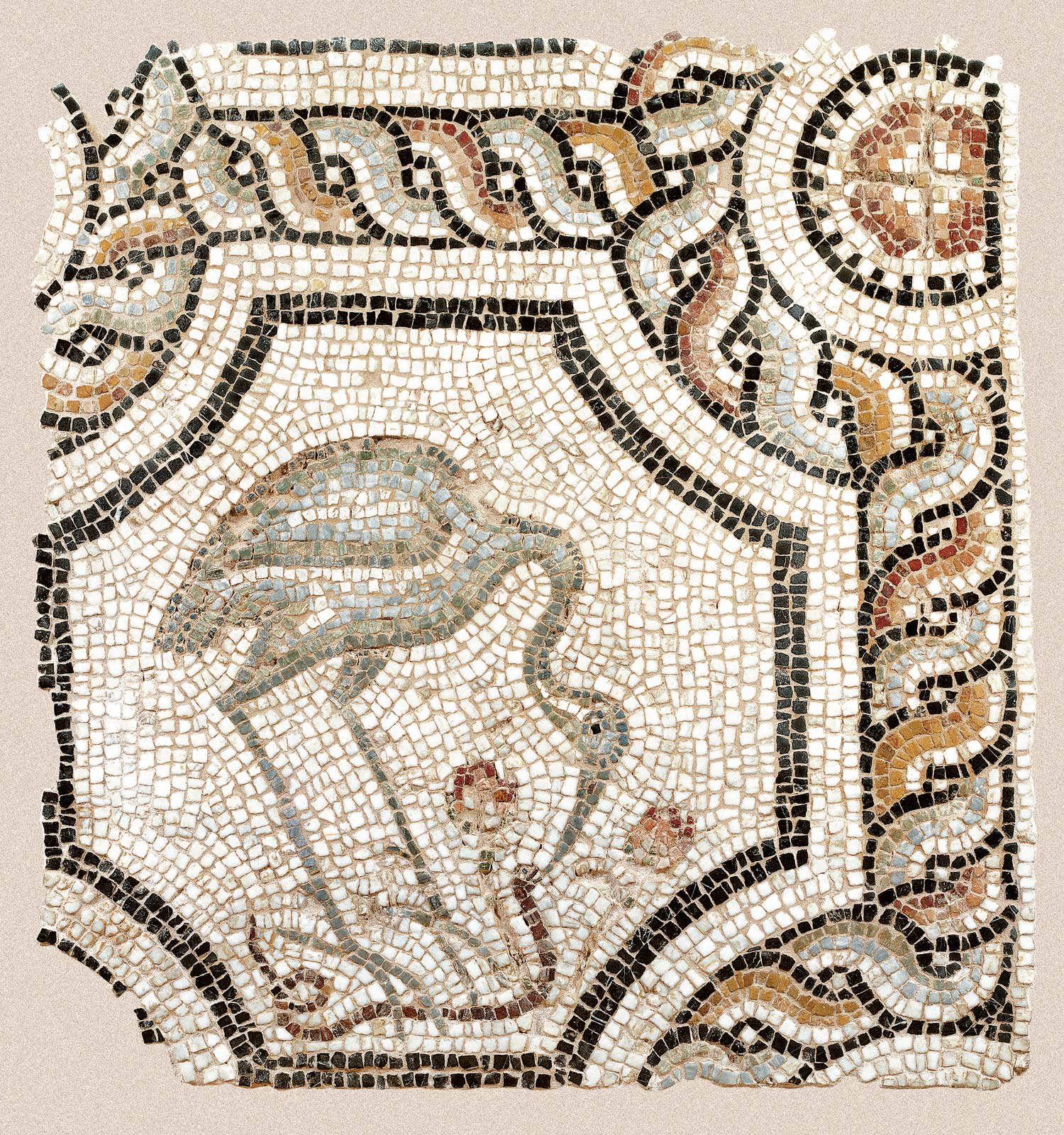

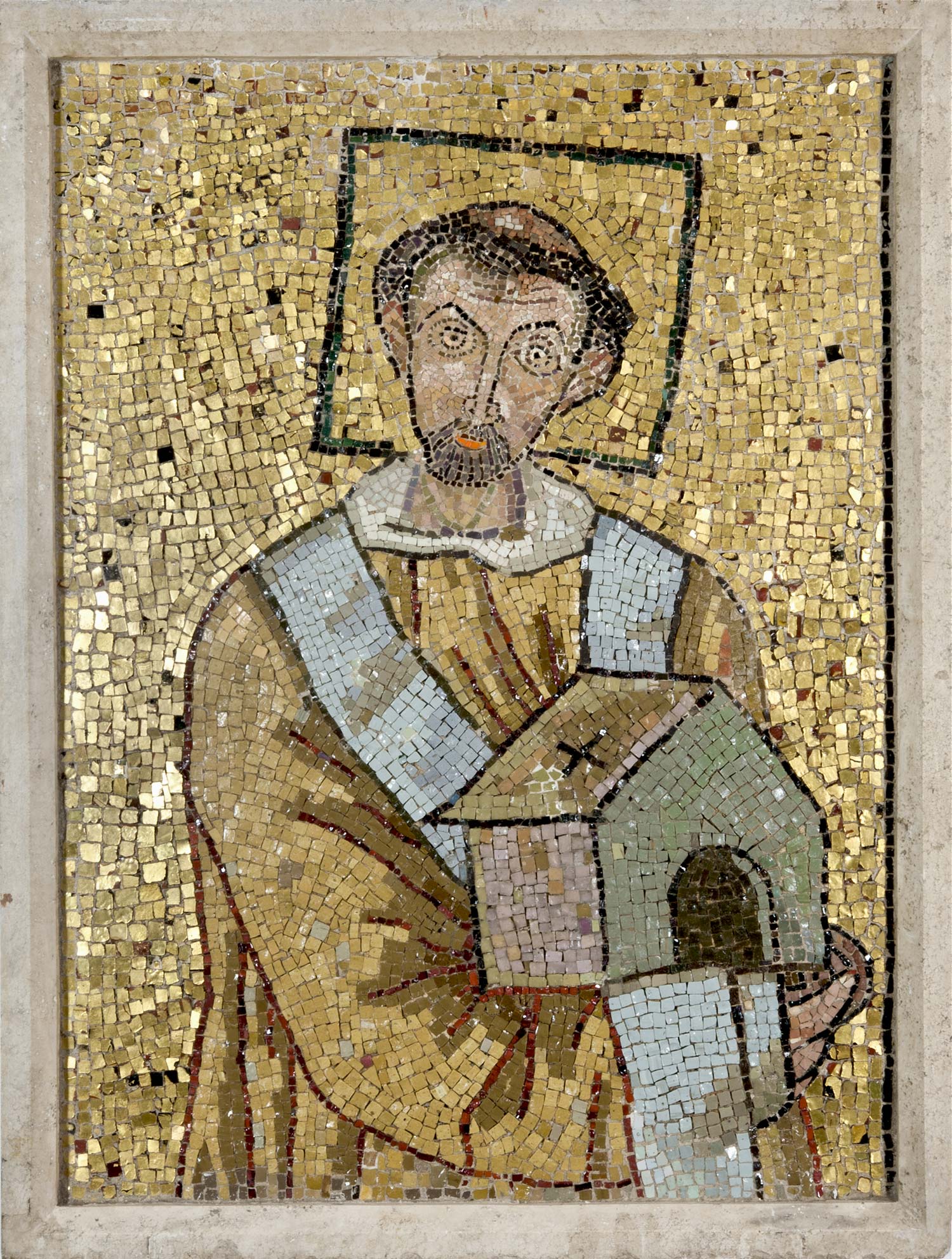

Architecture and decorative style, on the other hand, whether religious or civil, are recounted through various works, such as the beautiful 11th-12th century marble slab from the Museum of San Martino, depicting an eagle seizing a hare, above a typical ornamental motif of the period. Or the pluteus with the two beasts facing each other: emblematic pieces of this civilization that remind us not only of the importance of animal representations in the decorations, but also of plant motifs, another characteristic element of this style. The slab with the depiction of the tree of life, surrounded by animals, is a work that represents this style very well to us, but at the same time evokes mythical and ancestral eras. There is no lack of human presence in the representations, from the fragment of a wall painting depicting Saints George and Nicholas from the Church of the Virgin in Naxos (1260-1280) to the wall painting with a half-length military saint from the late 13th century from a church in Pyrgos and preserved in Athens. These works are imbued with a religious sense in which we perceive ancient reflections of Greek culture. The same we perceive in the mosaics, one of the best known and most characteristic artistic expressions of Byzantine culture. The mosaic panel with a portrait of Pope John VII from around 705, from the Fabric of St. Peter’s and made of glass tesserae, is an example, as is the fragment of a fifth-century mosaic floor from the Byzantine and Christian Museum in Athens. Closing the section on architecture is a large illustration that shows the viewer what Constantinople must have looked like from above in those years, and an extremely impressive video that tells, through virtual reconstructions, what a number of key places in Constantinople looked like at the time, such as the city walls, the forum, the baths, and the circus (the video can be viewed at byzantium1200.com).

Earring

Earring

The exhibition also has the merit of telling the visitor about everyday aspects of life in that period, such as crafts and trade. The theme of trade is addressed with a series of amphorae and coins, highlighting an extremely extensive empire, united in the cultural complexities of different populations, but with a common background, the Mediterranean.Craftsmanship, on the other hand, is exalted with a series of objects that are extraordinary and incredibly elegant even for modern taste: such is the case with the beautiful band bracelet from the Thessaloniki excavations, from the 9th-10th centuries, made of gold and glass, with cloisonné enamel inserts. So are a series of earrings, rings, bracelets and necklaces, some in bronze, others in gold, some of them enriched with enamels. Pieces that remind us of a lifestyle of the time, where art had a special place with architecture and mosaics, but where certainly luxury and a certain sophistication in accessories was not disdained.

This exhibition, thanks to these exhibits, accompanied by exhaustive explanatory panels, on the subjects and themes addressed, represents an effective window on the culture of this complex empire, managing to enhance so many of its many aspects and to promote in the viewer, as any exhibition should do, the desire to delve even deeper into this civilization, so important to our history and that of the Mediterranean. The exhibition ticket entitles visitors to a series of reductions at art venues in the ExtraMann network, at the Teatro Bellini and at the Gallerie d’Italia for the exhibition Artemisia Gentileschi in Naples.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.