The book in art throughout the centuries. What the exhibition in Genoa looks like

How have books been represented in art from the Middle Ages to contemporary times? It is a vast topic, if one thinks of how many paintings and sculptures over all these centuries have depicted a book in the hands of a portrait subject or in a still life, or even how, since the twentieth century, a work has taken the very form of a book. Yet this is the challenge that Agnese Marengo and Maurizio Romanengo, the two curators of the exhibition Books in Art. From the Middle Ages to the Contemporary Age, on display until July 14, 2024 at the Palazzo della Meridiana in Genoa. The idea of an exhibition project that would try to encapsulate in one show all the various ways in which thebook object has entered a work of art, crossing and involving the most diverse styles characteristic of each era, was already born when the small exhibition Straordinario e quotidiano da Strozzi a Magnasco was still running in the same Genoese venue. Human Contradictions in the Eyes of Painters, also curated by Marengo and Romanengo and built on the concept of opposites. Genoa had recently been named Italian Book Capital 2023, so why not imagine, albeit in the cramped spaces of the Palazzo della Meridiana (an issue the exhibition venue always has to deal with), an exhibition on the theme? Compared to the previous exhibition that had a little more than thirty works to which adequate space was left in the layout for each of them to allow for greater visibility, the current exhibition has ninety works, thus practically three times as many, but even on this occasion the spaces have been well balanced, especially in the first part; they are a little more crowded in the last part but nevertheless without creating a particular visual disturbance to the visitor, since in any case the path is well linear and orderly. And complete, which is not an easy thing because of the vastness of the theme mentioned earlier: in fact, all artistic trends are present (favoring almost always, as is obvious, works from Liguria or preserved in the region’s museums). Considering, however, that this tale in images is “only one of many possible” that “opens some doors and tries to point out others,” as the curators specify, to “suggest keys to interpretation starting from the book itself” and “intersecting the plane of the history of art in Italy with that of the history of the book.”

They start with two sculptures made by foreign craftsmen where the book object is in both the protagonist, but which differ in the depiction of the book first closed then open, indicating how with the coming of Christ the word through the Gospels is revealed to the faithful. The book is open in front of the speaker reading aloud in the cathedra in the bishoprics as depicted in the miniature on parchment with St. Gregory Pope in the cathedra, while it is depicted closed in the hands of the saintly teacher, probably St. Cassian, dressed in ermine-lined touch and cape. Of particular note is Ludovico Brea’sAnnunciation , where the book is placed open on the lectern between the Madonna and the angel; the pages seem to be moved by the air entering a very essential setting from which the landscape can be glimpsed, as is also the scroll with the angel’s words from his hand ending near Mary’s face: a very different image from the one instead depicted by Paolo di Giovanni Fei where Mary is caught by the apparition of the angel while she is reading and is therefore forced to stop reading the book, probably a Book of Hours because of its small size, and in order not to miss the sign she holds it with a finger between the pages. Then follows in a display case the large illuminated volume Gradual B, kept at the Biblioteca Civica Berio in Genoa and dating back to 1532, which presents a curious peculiarity: at the bottom of the page Bartolomeo Neroni da Siena known as the Riccio depicts himself and Adeodato da Monza while they are writing and illuminating the Gradual B itself under the directives of the patron Fra’ Angelo da Albenga, testifying to the intense relationship between the three subjects for the realization of the monumental illuminated masterpiece. From the large-sized volume we then move on to the small-sized books, such as the books, including some with antique bindings, here placed in another display case. Among them, curious is the case of Leonard Fuchs’ De humani corporis fabrica printed in Lyon in 1551, whose title was included in theIndex of Forbidden Books: however, it is disguised through collage so as to overcome censorship.

Also sixteenth-century are the portraits of the two doctors of law that follow: Francesco Filetto by Bernardino Licinio and Antonio Abbati by Federico Barocci, both of whom are probably depicted with the Justinian Codex, since in Barocci’s painting one can read on the spine of the book DEG.DE.REG.IVR indicating the Digest, that is, the anthological collection of texts by Roman jurists, while in Licinio’s painting one can read in the foreground the title of doctor under the name of the Venetian jurist. The latter rests his wrist on the book, which has a precious binding with gilded hooks and an ornate cut, while more practical and suitable for quick reference is the book that accompanies theBolognese lawyer: in fact, it has a non-rigid parchment cover with laces.

Then we move on to the seventeenth century with latbbigliata in luxurious robes and depicted with symbols of vanitas, then with a skull, jewelry, a candle and a book, the only non-ephemeral good, and with Anton Maria Vassallo’s Circe , the sensual sorceress of the Odyssey surrounded by animals and large open books to perform her spells. Instead, it is like a vexatious fan the small book held by the lady portrayed by Giacomo Ceruti in about 1725. In the nineteenth century, reading is placed at the center of learned conversations in cenacles, such as the Brescian one of Count Paolo Tosio and his consort Paolina, which the neoclassical Luigi Basiletti depicted in the painting on display in the exhibition: the members of the circle are here depicted intent on consulting various volumes. As of cultured readings, the 18th-century painting by François-Xavier Fabre that depicts Vittorio Alfieri and the Countess of Albany seated at a table also deals with them: in front of the countess one notices the volume of Montaigne’s Essais, included in the Index of Forbidden Books, while Alfieri’s left hand rests on the book of the Raggione Felice, Canto terza, a poem by the literary abbot and philosopher Valperga di Caluso, to whom the work is intended by his painter friend.

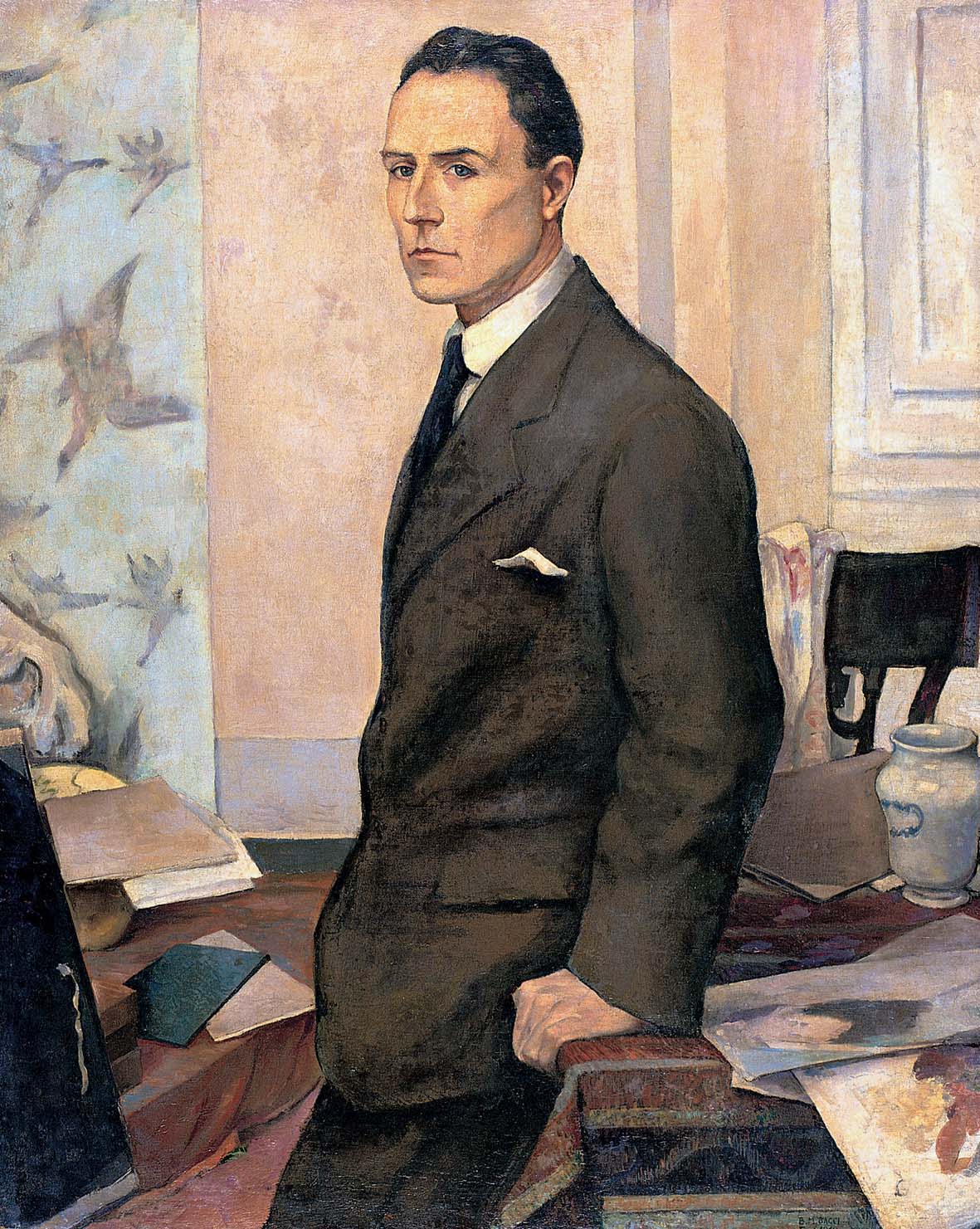

For the nineteenth- and twentieth-century section , the curators were assisted by Matteo Fochessati and Anna Vyazemtseva (the same people who curated the exhibition on nostalgia at the Ducal Palace): exhibited Francesco Hayez’sOdalisque Reading , as an example of the image of the woman without veils, covered only by the waist down, immersed in reading; Silvestro Lega’s Passeggiata in giardino, which testifies to the outdoor reading of two emancipated women during a walk in the green; and Ettore Tito’s Pagine d’amore, testimony instead to the shared reading of an appendix novel by a group of women as a moment of leisure and sociability under a pergola. The book is then present in the depictions of children engaged with school texts but also in leisure reading, as seen in the paintings by Armando Spadini (famous for being reproduced on the old 1,000 lire dedicated to Maria Montessori) and Giovanni Governato in the exhibition. Or in the portraits of nationally important personalities, as in the case of the portrait here of art historian Matteo Marangoni, who was director in the 1920s of the Superintendency of Florence, the Brera Picture Gallery and the Gallery of Parma, as well as a lecturer and author of books: Marangoni could therefore only be depicted surrounded by books and works of art in his studio.

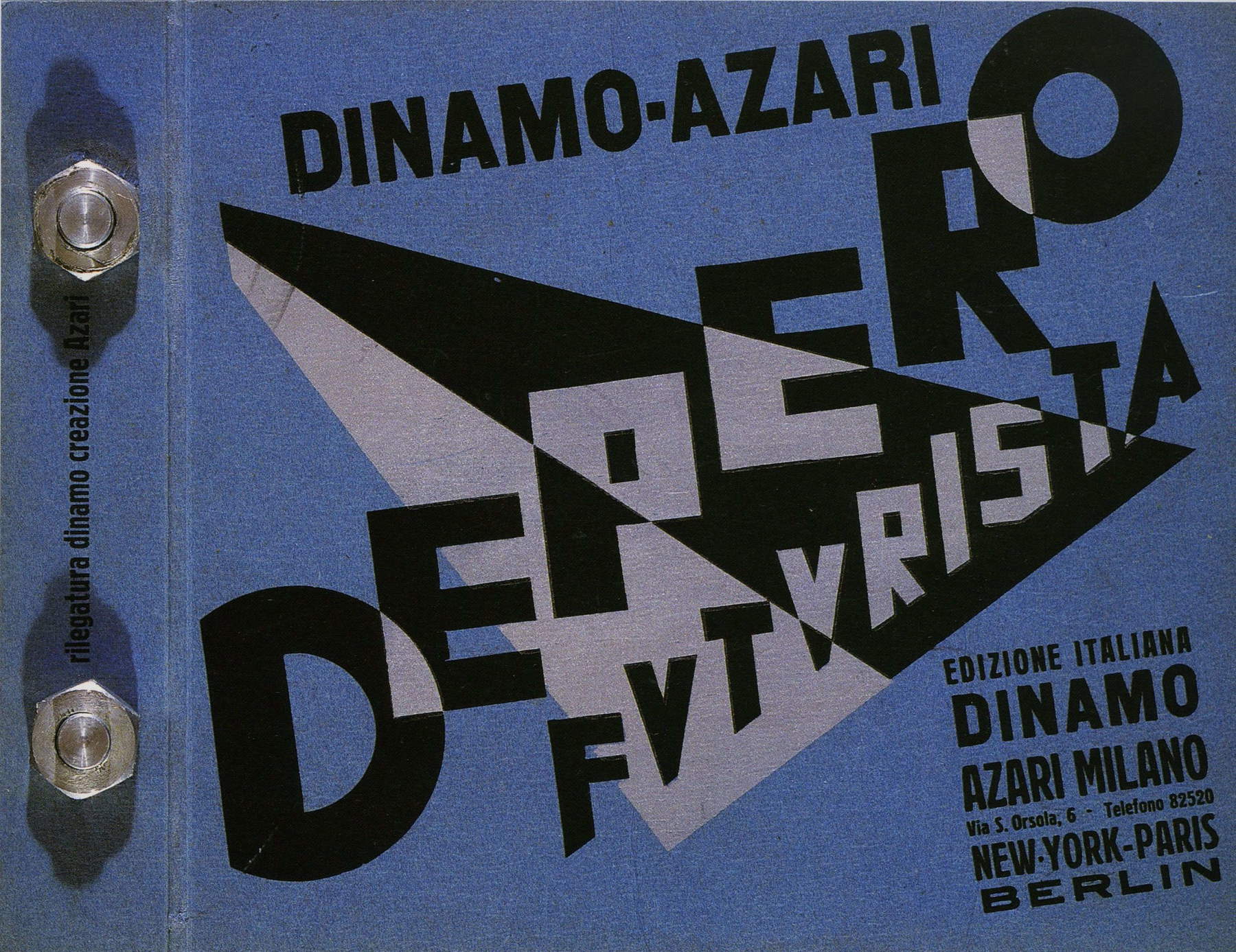

We then move on to theFuturist avant-garde with Fortunato Depero’s “bolted book,” toaeropittura with Un italiano di Mussolini made by Gerardo Dottori, in which Mussolini’s face stands out high in the sky amidst the evolutions of an airplane dominating the figure of writer and journalist Mario Carli depicted in a hieratic pose, to the constructivist graphics of Tullio d’Albisola and Bruno Munari with the volume The Lyrical Watermelon, ending with Guido Galletti’s Portrait of a Young Girl , an expression of youth organizations during the Fascist regime. A close comparison between works of art and book covers is also proposed, documenting how the latter, previously unillustrated or provided with original illustrations, began between the 1930s and 1940s to reproduce works of art based on the contents and themes of the book.

The last part of the exhibition, for which the curators were assisted by Laura Garbarino, is devoted tocontemporary art. It is here that the book is often dematerialized, that it becomes a tool for reflection on its own essence, that the pages accommodate a gesture, an action, becoming themselves a work of art. Here then is Vincenzo Agnetti’s monumental Libro dimenticato a memoria, in which the space reserved for writing is physically removed, Irma Blank’s lines of color, Emilio Isgrò’s erasures, Mirella Bentivoglio’s marble book, Alighiero Boetti ’s volume listing the world’s rivers, from longest to shortest, Betty Danon’s visual poems, Claudio Parmiggiani’s presence-absence of books, Maria Lai’s sewn books, Eugenio Miccini’s framed monochrome dark velvet book.

The exhibition is thus a tale through the centuries of how the book has entered art, with works not only from Liguria but belonging to the national panorama, and from museums, foundations and private collections in Italy. The concluding event of the Genoa Italian Capital of the Book program, if the aim of the exhibition is to combine the history of art with the history of the book, one grasps in the opinion of writes better the former than the latter, which remains more difficult to grasp because it has to be deciphered within the works. More useful in this sense is the catalog that accompanies the exhibition, which contains essays on the subject, particularly the introductory one by Graziano Ruffini that traces a path on the form of the book and its history, as well as one by Margherita Orsero on the manuscript book in the Middle Ages. Other topics covered in the catalog include iconography and the art of the book between the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries(Marie Luce Repetto), the libraries of the Palazzi dei Rolli in Genoa(Giacomo Montanari), the library of Palazzo Spinola di Pellicceria(Gianluca Zanelli), and portraits of sixteenth-century scholars in Palazzo Rosso(Martina Panizzutt). The volume also includes paintings exhibited for the occasion in other museums in the city, such as Palazzo Rosso, Palazzo Reale, Palazzo Spinola, Accademia Ligustica di Belle Arti, and Wolfsoniana. Indeed, the idea of having expanded the exhibition outside Palazzo della Meridiana with other book-related exhibition events is valuable

A theme that of the book in art spans all eras, all styles and all techniques, as universal as reading has reason to be.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.