To enter Lucio Fontana’s creative process, his thoughts and ideas, to grasp the seductive complexity of his work, the theoretical lucidity that sustains the beauty of his works, the motivations behind the sculptures, the holes, the cuts. To be guided through his works by following the thread of his reasons, expressed with that vivid eloquence and sarcasm that often, or almost always, inflamed his words whenever he found himself having to discuss the basis of his work. To follow Fontana as he talks with Carla Lonzi, in that famous conversation later merged into the equally famous Autoritratto, the collection of interviews with artists that the great critic published in 1969, and to find feedback in the works. One could sum up in simple words the exhibition Lucio Fontana. Self-Portrait, the fine project curated by Walter Guadagnini, Gaspare Luigi Marcone and Stefano Roffi that the Magnani Rocca Foundation in Mamiano di Traversetolo is dedicating to the father of Spatialism. The idea is interesting: to retrace Lucio Fontana’s career through his words, arranged throughout the tour, in the midst of some 50 works, to direct the visitor to an understanding of the origins of those works that have indelibly and decisively marked the history of art. Without forcing, without constraint: let the artist do the talking.

What emerges, as a result, is an exhibition that is surprising for the intimate slant the path takes. It is as if the audience is invited to that conversation in two between Fontana and Lonzi, whose full audio, recorded on October 10, 1967, is played in a first room that introduces the visit. A “maieutic dialogue for both of them,” Marcone writes in the exhibition catalog, which “has the form of a ’spiral’ with topics introduced or hinted at then taken up or deepened with parentheses and digressions” and is centered on certain “certainties” with which “the artist rewrites or retells his story looking at the past, present and future.” A dialogue that represented a new critical act, an innovative way of relating to the artist. Lonzi first became acquainted with Fontana’s art in 1959, Lara Conte reconstructs in the catalog: that year a solo exhibition of the Italian-Argentine artist was held at the Galleria Notizie in Rome, presented by Enrico Crispolti, who wrote the first contribution on Fontana for the occasion. Lonzi would first write about him in a review on that year’s edition of Documenta, where Fontana was present with some of his early Spatial Concepts: the critic called Fontana’s art “painting of cuts,” pointing to it as “a concise relationship between the purity of spatial architecture, the sensitiveness of the pictorial epidermis and the limpid yet violent elegance of the blade stroke.”

Thereafter, Lonzi would further study and explore Fontana’s spatialism, and would also have the opportunity to present an exhibition of his work. And his conversation, published in abridged form in Self-Portrait and now reproduced in full (including the interruption Fontana was forced to take to answer a phone call) in the exhibition catalog, constitutes one of the fundamental contributions to understanding Fontana’s art. And the originality of the exhibition lies not so much in the novelty of the proposal, although it is an incontrovertible fact that it is one of the most comprehensive retrospectives on Fontana that has been seen in recent years in Italy (the selection touches on almost the artist’s entire career, with a few loans but all extremely significant: it is therefore an important opportunity for the public to learn more and deepen their knowledge), but in the choice to emphasize the centrality of Carla Lonzi’s intervention and to elevate it to the de facto “guide” of the exhibition.

The visitor first encounters a terracotta Head of a Girl, which is placed in the room that houses Renaissance works from the Magnani Rocca collection (Fontana’s sculpture is placed in front of Titian’s Sacred Conversation ) to send the visitor back to Fontana’s very first season, since the sculpture dates from 1931, gives an account of the sculptor’s beginnings in an almost expressionist sense and above all, Paolo Campiglio points out, “highlights [....] that the questioning of the means and language of sculpture could also be conducted within sculpture itself, in the seductive realistic portrait.” We then move on to the first room, which gives ample space to Fontana’s theoretical activity, with a reprise of one of his most relevant writings, the Manifiesto Blanco that the artist penned in 1946 in Buenos Aires together with Bernardo Arias, Horacio Cazeneuve, Marcos Fridman, Pablo Arias, Rodolfo Burgos, Enrique Benito, César Bernal, Luis Coll, Alfredo Hansen and Jorge Roccamonte. Fontana’s first art manifesto set some firm points that would later lead to the manifestos of Spatialism: first, art is a “vital necessity of the species.” Second, “ideas cannot be rejected.” Third, the proposal is the “overcoming of painting, sculpture, poetry, music” in the name of “an art more closely in accord with the needs of the new spirit.” Finally, time and space are the foundational elements of the new art. The reference to Baroque art, inescapable for Fontana and present from the earliest lines of the Manifiesto Blanco, is made explicit in the exhibition by the presence of a Transfigurazione of 1949, a ceramic coming from the Cagnin collection in Parma, as well as by the sketches for the bronze Minerva in the atrium of the State University of Milan, dated 1956. But it is above all from ceramics, with its voids and solids, with the light refracting on the glazed surfaces, with its vertical tension that the desire to conquer space begins to express itself. And the ceramics at the beginning of the path is also a precise reminder of the conversation with Carla Lonzi, which opens with a reflection on technique: “the most logical material was ceramics,” says the artist, because it could be shaped and molded directly and without intermediate steps that, according to Fontana’s vision, could have altered the artist’s initial intent.

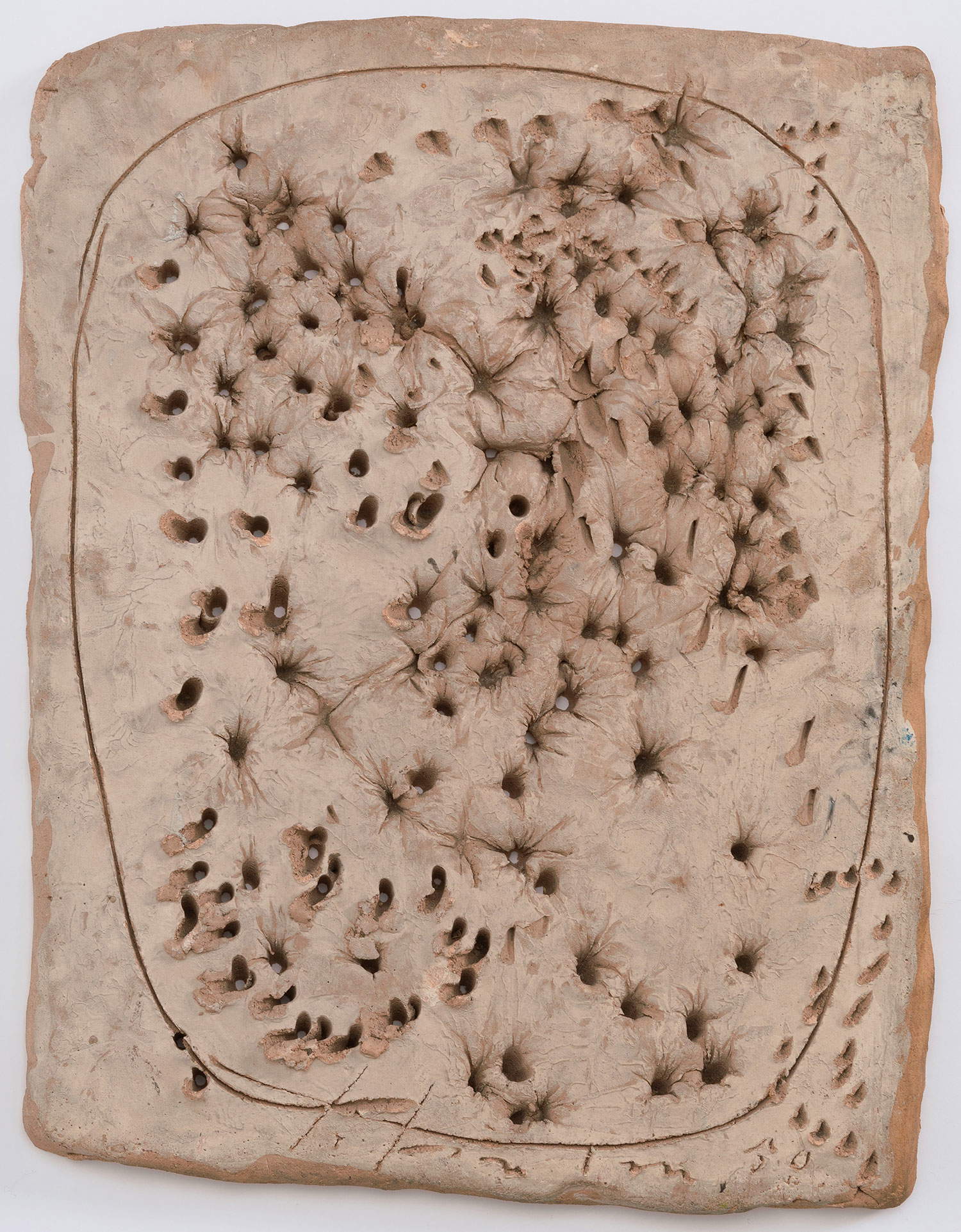

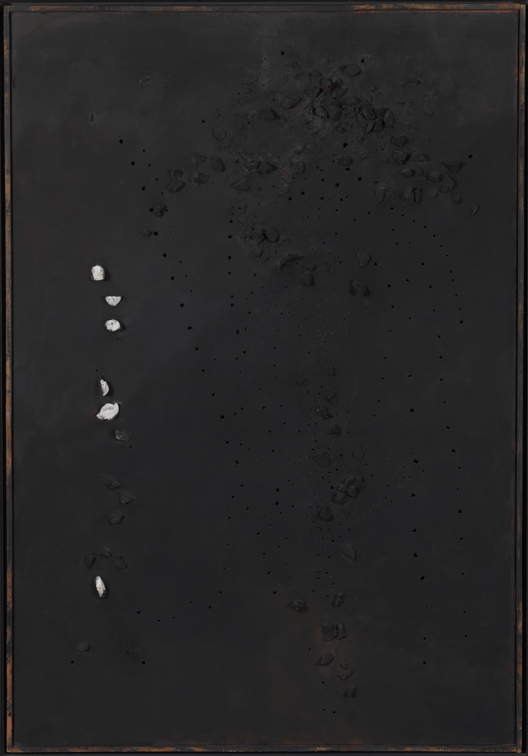

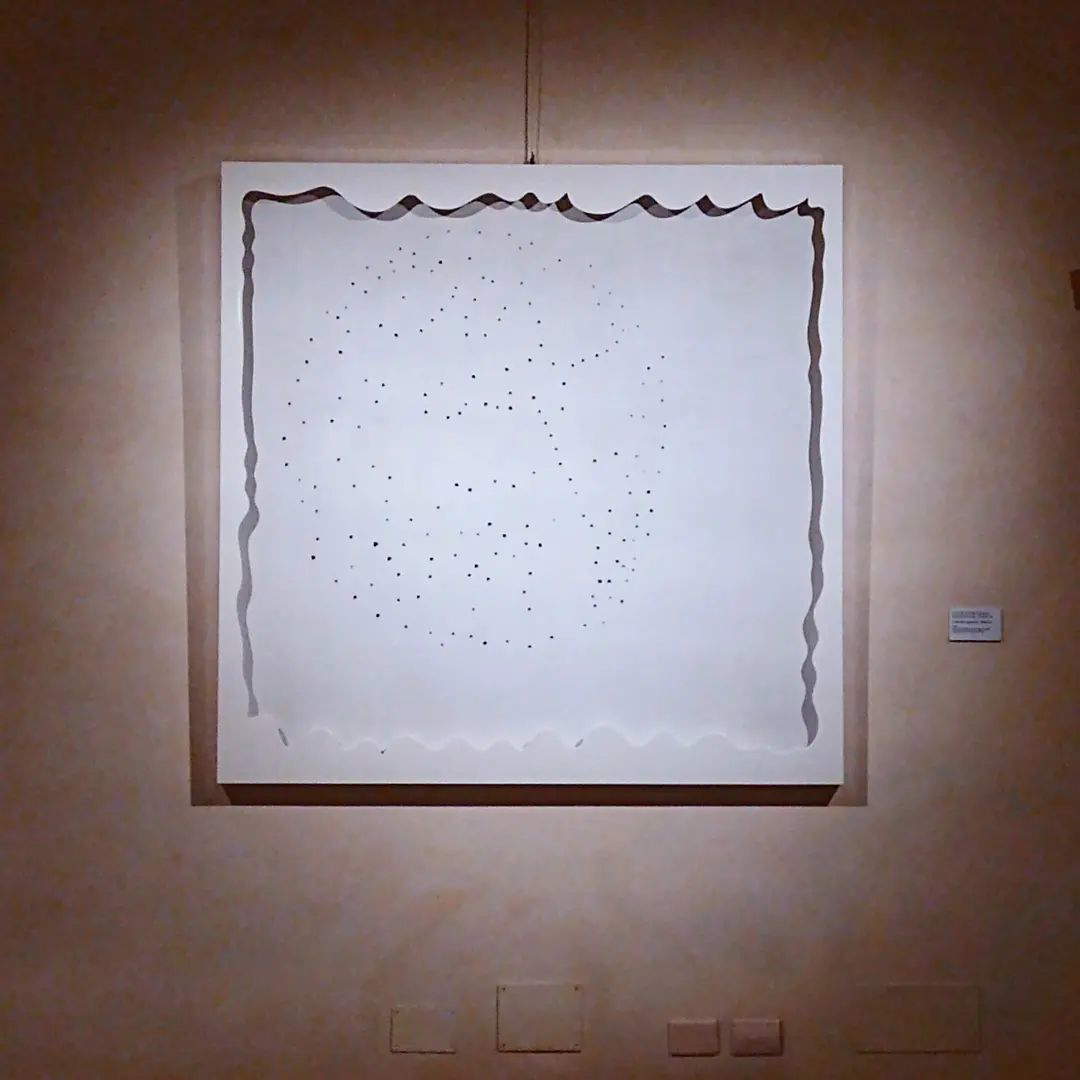

To the “holes” and “cuts” Fontana would have arrived by degrees, and the exhibition in Mamiano di Traversetolo well attests to this process of approach, which from the perforated papers leads, on the first, to works of great immediacy, such as Spatial Concept (bread), a 1950 terracotta, on loan from the collection of the Fontana Foundation (as are most of the works on display), where the first holes disrupt a surface that resembles the shape of a loaf of bread, in its modeling and colors, and which transform an object that refers to an element of everyday life into an open gateway to the cosmos. Fontana’s is, moreover, not a linear path, and the exhibition intends to give evidence of this aspect as well: his research was fraught with obstacles, second thoughts, and steps backward. A Spatial Concept from 1955, with holes and pieces of glass applied to the canvas, on loan from the Mart in Rovereto, is the clearest demonstration of this: “when I put the stones,” Fontana told Lonzi, “it was to see if I could overcome, and instead I took a step backward, you see ... because you do things even wrong, believing you are going forward ... instead, believing that with the stones light would pass through, create more the effect of movement, like this. And instead, I realized that I have to be just with my pure simplicity, because it’s pure philosophy, more like ... call it even spatial philosophy, you can call it cosmic, can’t you?” So here they are, those holes stripping down to a simpler dimension (a Spatial Concept from 1960-1961, again from the Mart: the only concessions now are the arrangement of the holes and the color) and then arriving at the poetry of the cut.

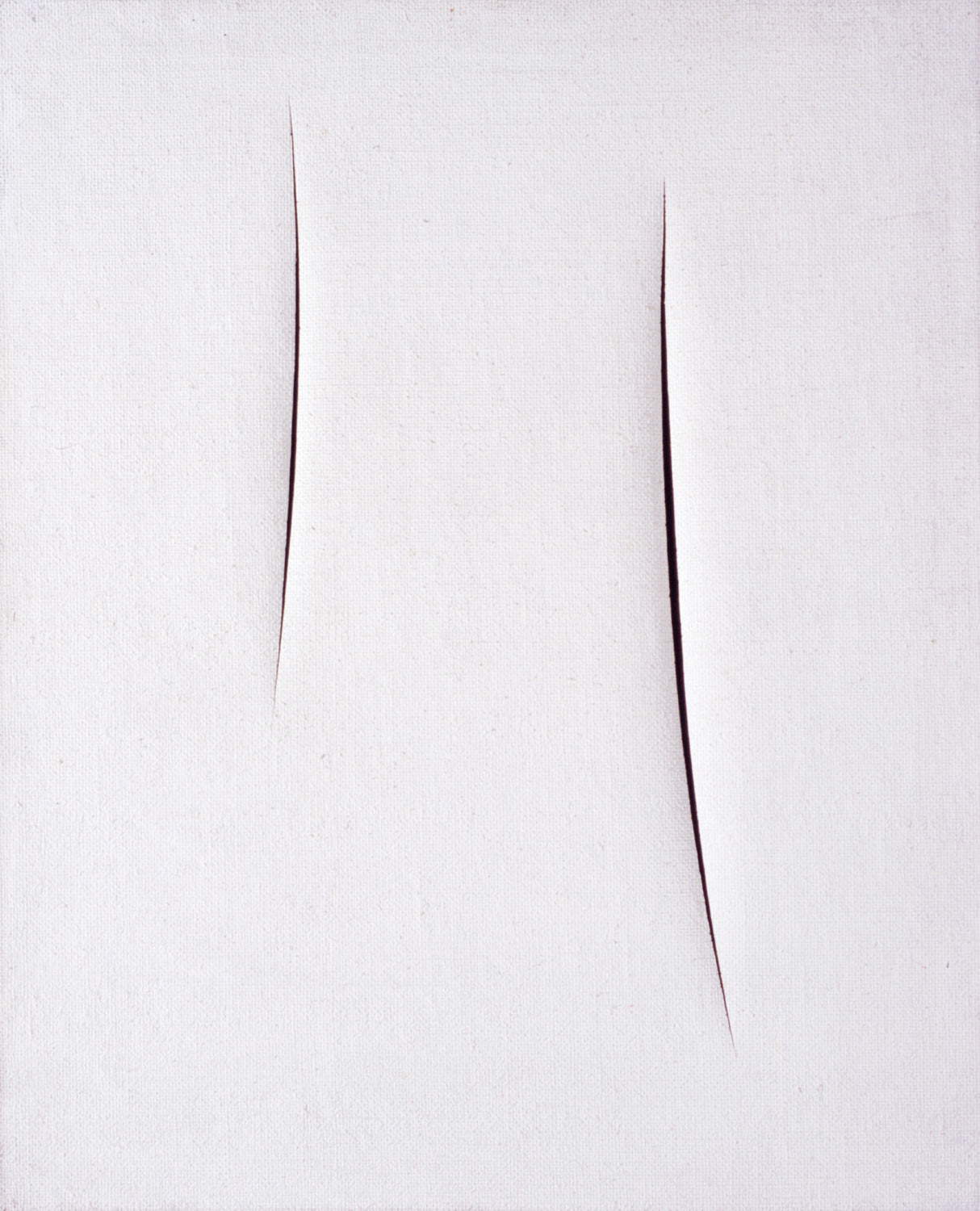

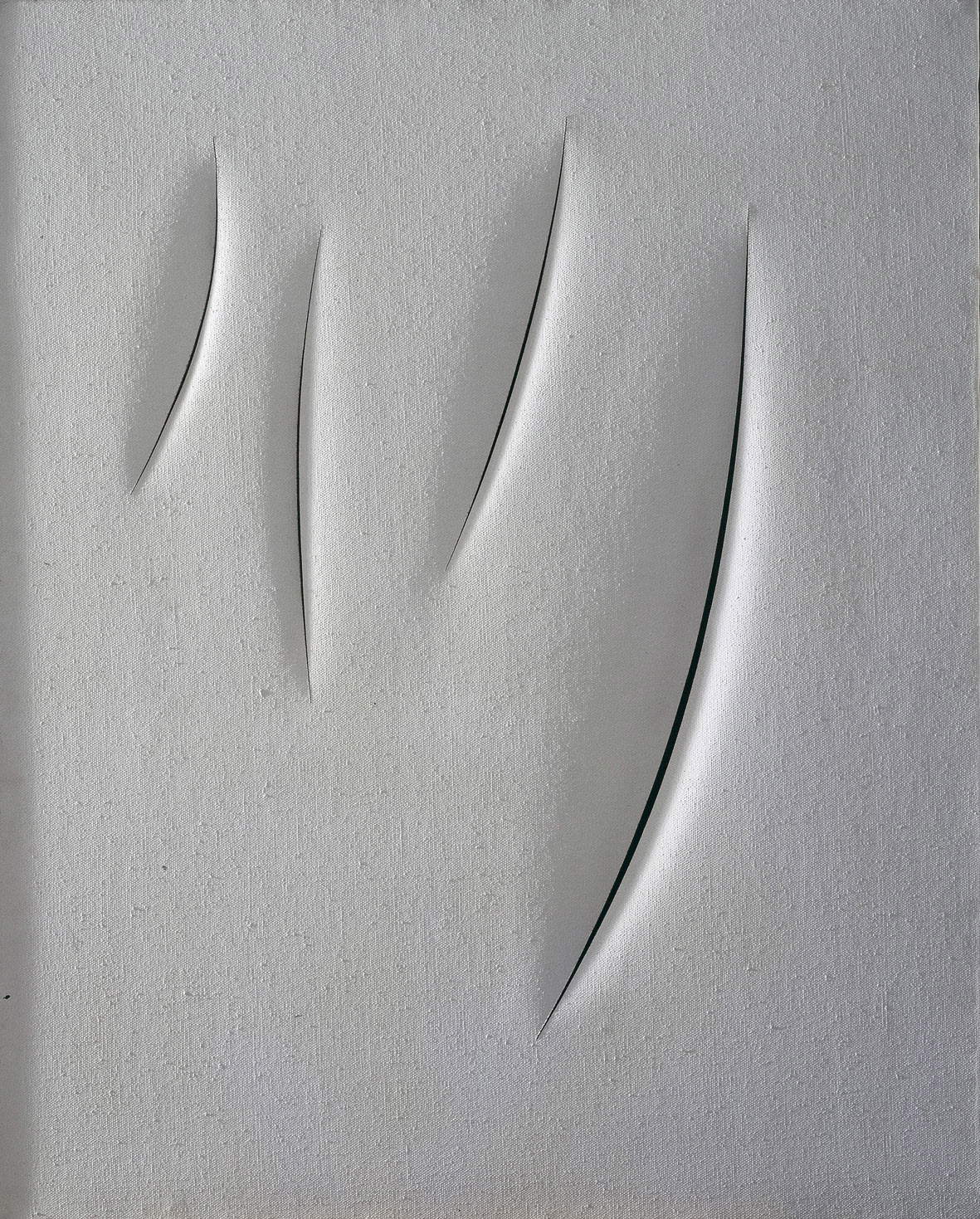

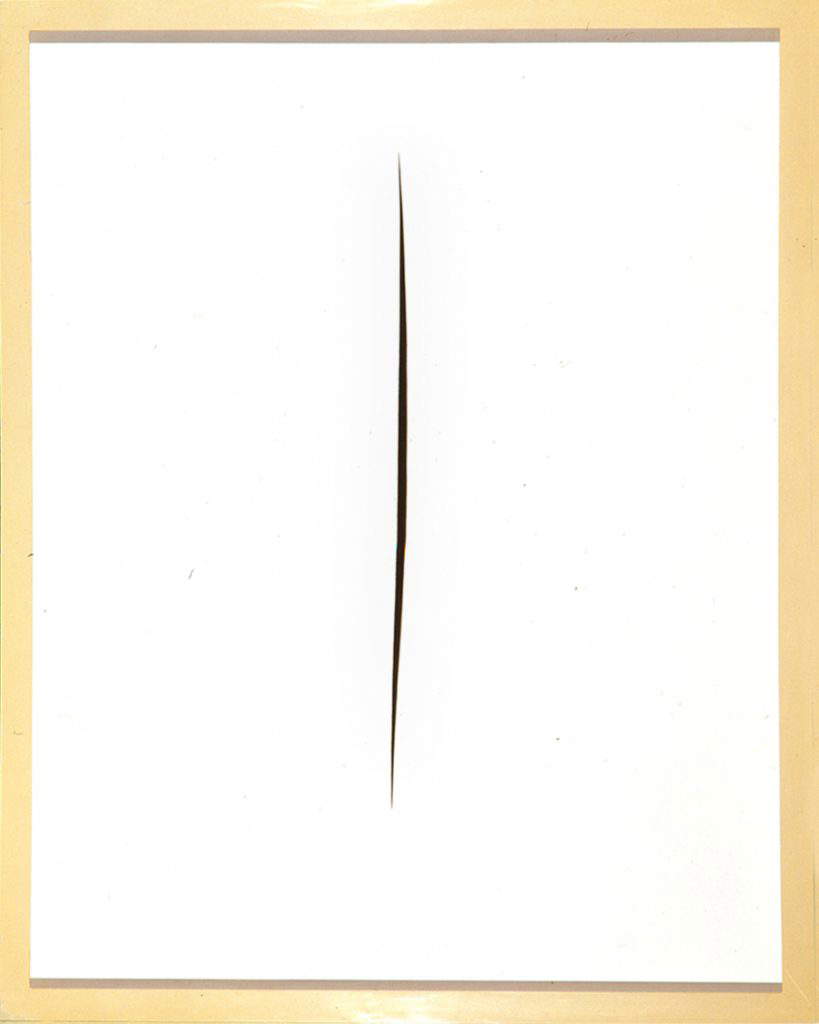

In the second room of the exhibition, four cuts are lined up, demonstrating the variety of solutions imagined by Fontana but also, wanting to see the other side of the coin, their repetitiveness (the artist would later bluntly admit that he would produce a large quantity of cuts not for artistic reasons, but because high were the demands of collectors, who wanted to have his Attesa, as Fontana had called his cuts). Fontana was giving a new direction to that conquest (the hole, even before the cut) that gave meaning to a life’s research: “My discovery was the hole and that’s all: I am happy even to die after that discovery... whereas, before, I felt nothing, I could never... all this research of mine... ’Fountain jokes, teasing’... it was just this restlessness, wasn’t it? Just to find ... to find something that was always on my mind, right?” With his holes and cuts, Fontana opened doors to infinity. Not only that: he invited everyone to go beyond the surface of the work to begin a journey into reality. He achieved the “change in essence and form” that he had been seeking since Manifiesto Blanco. An art “based in the unity of time and space,” he would write in the Technical Manifesto of Spatialism. An art that emphasizes the need for action.

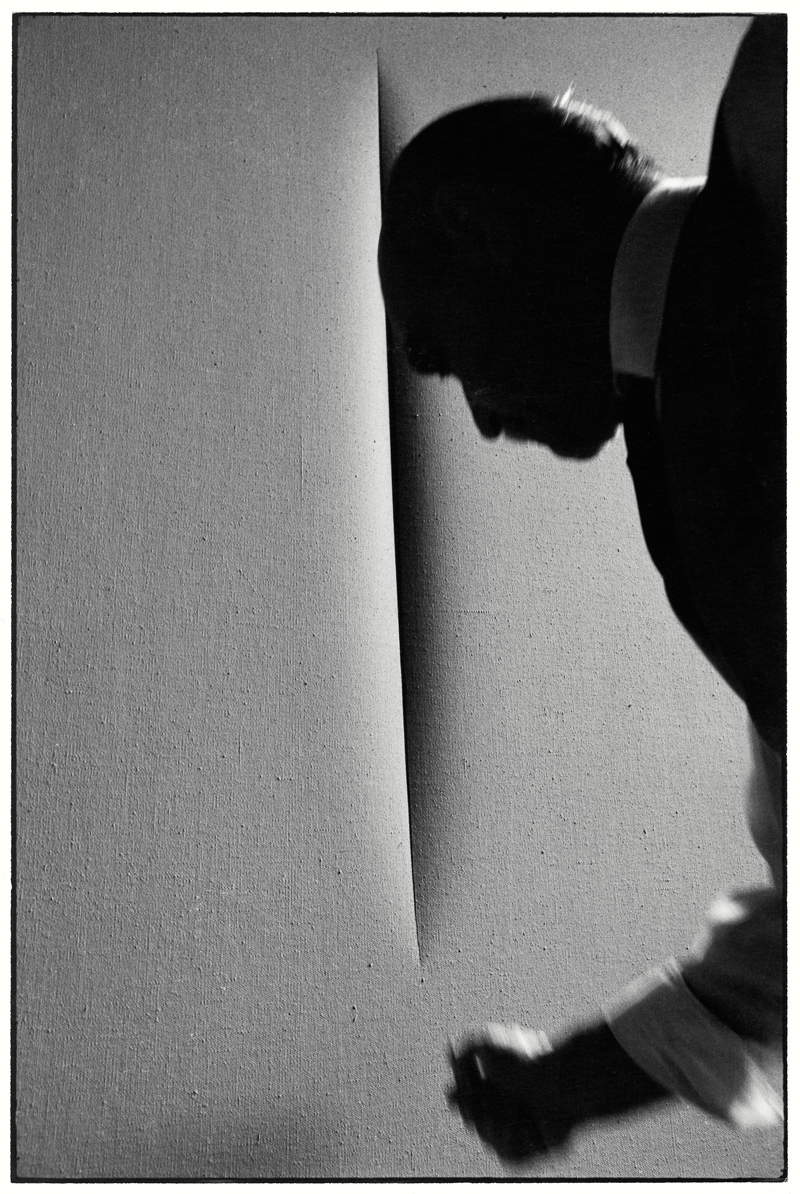

To get to the cuts starting with the holes, Fontana would take a decade at least. The instinctive, almost violent charge of the holes found in the cuts a sense of relaxation, “of spatial calm,” and of “serenity in the infinite,” wanting to borrow the words Fontana used to describe his Attese in an interview with Giorgio Bocca. In the exhibition, the task of underlining the differences between holes and cuts is entrusted to another ideal guide, Ugo Mulas (the famous photographs depicting Fontana while making a cut, which as is well known were designed with the intention of making it look like a natural and instantaneous gesture when in fact each cut required a technical procedure that was neither immediate nor simple), for whom cuts detected a kind of dual nature in Fontana, one that was almost primitive and one that was instead calculating: “this precisely physical, instinctive let us say, almost automatic force of his and his great desire to control it, to master it, to arrive at a conceptual clarity; in short, he was a painter between two moments, between two worlds; that is, a painter who felt very much perhaps all the motives that were at the basis of renewal.” In his cuts, in short, there is also the life of the human being with its contradictions.

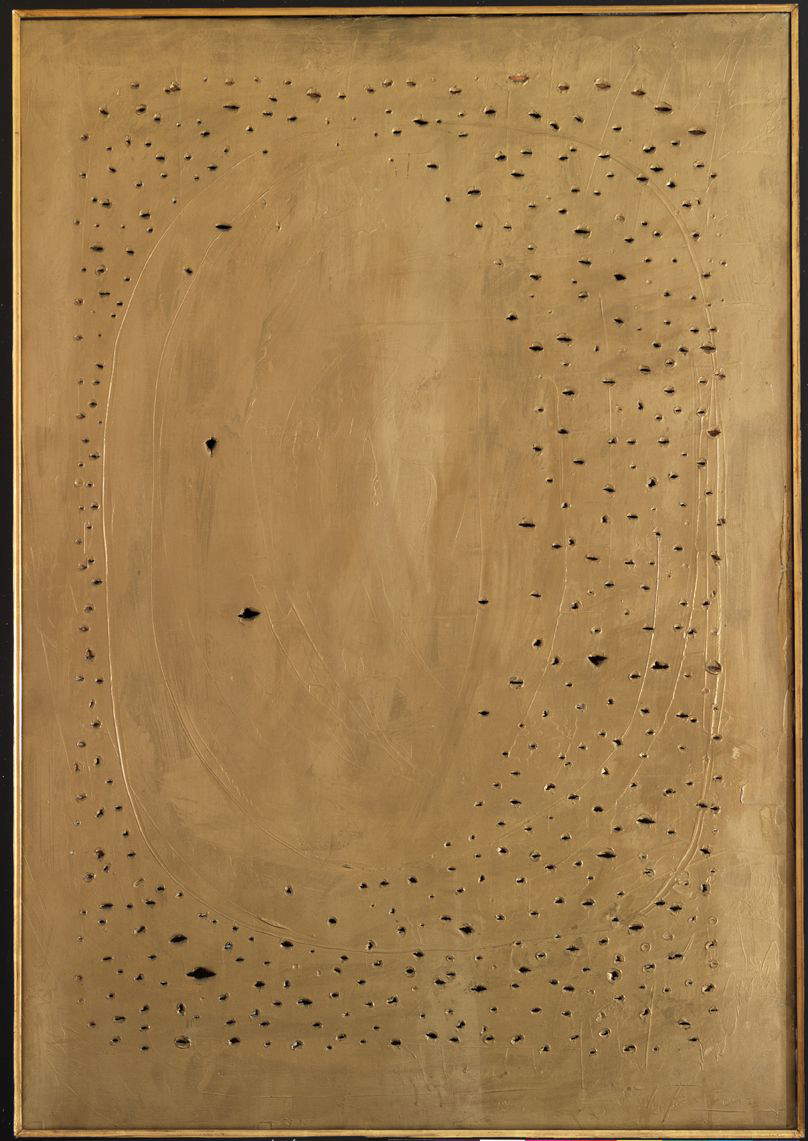

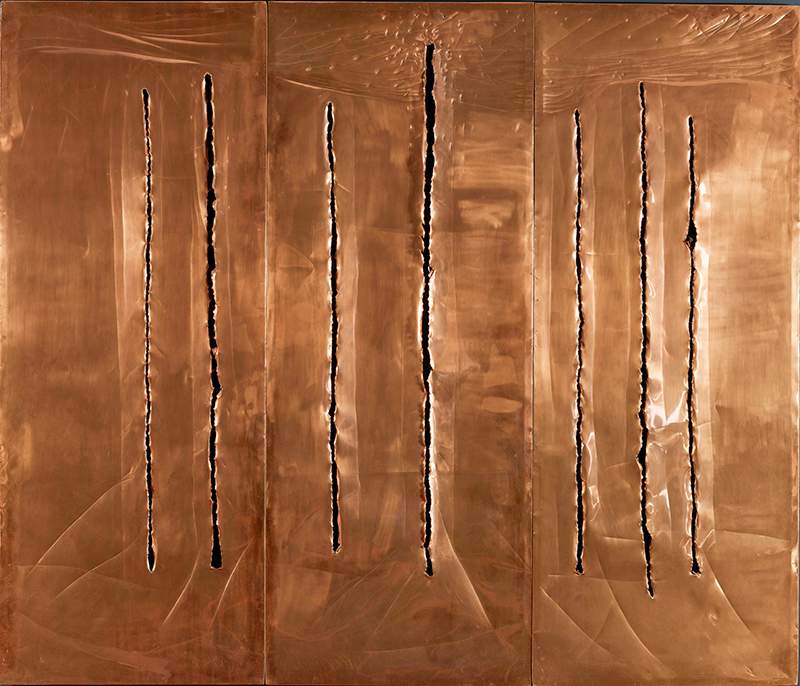

The following rooms grant the public more insights into further aspects of Fontana’s work. One section is devoted to sculpture: the Fiocinatore, a colored plaster cast of 1933-1934 that stands at the beginning of Fontana’s career and demonstrates his familiarity with the languages of tradition but also his willingness to go beyond them from the outset (the golden patina that covers the figure of the fisherman, writes Maria Villa, “sanctions an important step in the definition of a new language,” since it “gives the work an anti-naturalistic, almost abstract value, which rejects any mimetic intent” and in fact already stands in a break with tradition). Then there are the Natures, large cut spheres (Fontana “breaks balls,” his detractors used to say) that allude to the simplicity of nature (the spherical form) but also to its imperfection (the gash that alters matter), and on the central wall the famous Spatial Concept. New York, a large work from the Metalli series that matured during a New York sojourn by Fontana, who by etching a large copper plate offers the relative the suggestion of the skyscrapers of the American city. After a passage in which a number of sculptures exploring the possibilities of holes on three-dimensional surfaces are exhibited, we come to the last room that aligns two works, a Teatrino and an End of God, to investigate the extreme developments in Fontana’s art. The Teatrini, executed between 1963 and 1966, are space studies where some figures move against the background of delimited wings to create hypotheses of “realistic spatialism,” using an expression of Fontana’s, “forms that man imagines in space.” The End of God belongs to a series of pierced oval canvases that, Fontana would say in an interview with Carlo Cisventi in 1963, “for me signify the infinite, the inconceivable thing, the end of figuration, the principle of nothingness.” The conquest of space, Fontana told Carla Lonzi, had made it clear that faith is a fact of consciousness. Human beings discovered infinity and eternity: and then, human beings would have to abandon “the materialistic ambition to be represented in matter, marble, bronze, believing that they would be received by posterity.” The End of God thus has no provocative intentions, as many thought at the time and as they still think today: it is a work that Fontana wanted to be taken seriously because of the seriousness of the themes it addresses, beginning with the idea of a new representation of the infinite (for Fontana, the word “God” was not to be understood in a religious sense: it was, if anything, a way of expressing the end of figuration) and by the need to reconsider the origins of life (many, starting with Gillo Dorfles, have noted how the egg shape of The End of God refers precisely to the iconography of birth, even of the Immaculate Conception if one wants to give this series a religious meaning).

Lucio Fontana. Self-Portrait concludes with a selection of works by different artists (from Giulio Paolini to Enrico Baj, from Alberto Burri to Enrico Castellani, from Piero Manzoni to Luciano Fabro) that moves in two directions: the first, to give an account of the research carried out by Fontana’s contemporaries and to show in parallel how his lesson was received by younger people (Castellani’s art, for example, would be inconceivable without Fontana’s investigations), and the second to show how attentive Fontana was to young people, towards whom he had great expectations and hopes, believing that Italian art was very vital, and considering the Italian scene even superior to that of the United States, and this not out of mere chauvinism (Fontana’s negative judgment of Vedova, to whom he reserves very sharp words in his conversation with Carla Lonzi, shows that he did not look at nationality), but because he believed that his and Manzoni’s (but also Yves Klein’s, to mention a non-Italian artist) achievements were (and were) decidedly more important than those of Pollock and the American abstract expressionists. Some of the works in the exhibition are also mentioned in the conversation.

At the Fondazione Magnani Rocca, therefore, the path of knowledge on the great art of the 20th century, for which the Parma museum has now become an increasingly inescapable point of reference, continues with an exhibition with a distinctly popular approach but which also finds the reasons for its interest in having elevated a profoundly innovative critical intervention, that of Carla Lonzi, to a central moment around which to build a review. An intervention that represented an important novelty, adequately remarked by Lara Conte: “Lonzi wants to abolish the distance, that filter that is established between the critical act and the artist’s thought, in order to draw a greater adherence to the existential experience, and better understand the creative process, the working techniques, avoiding that the critical practice can exercise a problematic and questionable interpretative action.” The suggestion is not to skip the introductory room with the audio of the conversation, as is often done when visiting an exhibition (it would be interesting to know the percentage of the public that lingers to listen to the multimedia introductions), but to stop and listen to Fontana’s words, which will echo throughout the exhibition: it will seem as if you have the artist at your side, to be in his company while observing his works (the Magnani Rocca Foundation exhibition succeeds in giving this wonderful suggestion to visitors, and for this alone it would deserve to be visited).

One will return to the lush garden of the Magnani Rocca with the feeling of having met a man who not only marked a fundamental moment in the history of world art, but who was able to see beyond it, who suggested a philosophy of “nothingness of creation,” an art of liberation from matter. The human being will always exist, according to Lucio Fontana, but in hundreds or thousands of years “he will become a simple being, like a flower, a plant, and he will live only by his intelligence, by the beauty of nature, and he will purify himself of blood. It will live by the achievements of science, it will become an evolved being, it will stop having thoughts of dominance over its fellow man and other living beings, ”wars will end." Lucio Fontana had envisioned an art form that somehow anticipates this human being of the future. Probably because he too was a man living in the future.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.