by Federico Giannini (Instagram: @federicogiannini1), published on 20/06/2018

Categories: Exhibition reviews

/ Disclaimer

Review of the exhibition 'Birth of a Nation. Between Guttuso, Fontana and Schifano' in Florence, Palazzo Strozzi, from March 16 to July 22, 2018.

Interestingly, in the entire catalog of the exhibition Birth of a Nation. Between Guttuso, Fontana and Schifano, currently underway in Florence at Palazzo Strozzi, the word “nation,” minus the repetitions in the title, registers only five occurrences. The period examined by the review is, roughly speaking, the two decades from 1948 to 1968, that is, from the coming into force of the Constitution to the Great Contestation (and wanting to circumscribe it even more, one could fix the term post quem to 1953, the year of some fundamental events for the culture of the time, such as the Picasso exhibition in Milan, the release of Fellini’s I vitelloni, Burri’s first international exhibitions: in this sense, it is possible to consider the Palazzo Strozzi exhibition almost as a continuation of LItalia sè desta: 1945-1953, held at the MAR in Ravenna in 2011). For Luca Massimo Barbero, curator of the exhibition, “these early 1960s represented a moment of rebirth for Italy, in which the nation recognized itself in the arts and their contemporaneity. Even with organic and even endemic resistances, the country feels that it is jointly represented by the artistic concept.” However, it is not clear in what arts and in what contemporaneity Italy of that time had recognized itself: the artists presented in the exhibition, by the curator’s own admission, did not represent “what was currently exhibited in the galleries and museums of our country at the time, much less what was commercially successful with merchants and collectors,” since the taste of the time rewarded “illustrative figuration, intimist naturalism, the homegrown declinations of an informal art superficially assumed as a stylistic feature, or a realism declined between ideological commitment and literary citationism.” And if the avant-garde movements of the 1960s met with little success among gallery owners and collectors, let alone what perception the public might have of them: and the very public that is supposed to “recognize” itself in contemporary art, fifty years later still struggles to find affinity with many of the artists of the time, even if they are now largely historicized.

And all this was happening, moreover, at a time when posing the problem of theidea of nationhood, for many, was tantamount to resurrecting ghosts that everyone wanted to leave behind. Indeed: the post-World War II years were precisely those in which the idea of nation, after the devastation of the world conflict, entered a deep crisis. A historian like Renato Romeo, as early as the 1970s, pointed out how the search for national values, in the postwar period, had had to give way to the new Europeanist demands, the ideological clash between liberal democracy and communism, and the rise of political movements that did not identify with national motives. In essence: none of the artists in the exhibition (with the exception, perhaps, of Luciano Fabro) cared about the concept of “nation,” none of them cared about “bringing a nation into being.” The prevailing feeling was one of indifference to national ideas, and the drives that animated them were other. This was well remarked on in the pages of Corriere Fiorentino, speaking precisely about the exhibition at Palazzo Strozzi, by Franco Camerlinghi, a historian of the Florence-based PCI, who recalled how Italy’s strong territorial and social divisions, from 1861 to the present, have always cast doubt on the existence of unifying national characteristics, and how, given also the fact that many of the artists in the exhibition were close to the PCI or even militant (and therefore interested, if anything, in revolution rather than nation), we were moving within a divisive political climate in which, to borrow a thought from Emilio Gentile, the sense of the party replaced the sense of the nation. But even assuming Hobsbawmn’s approach, according to which the nation can be defined only a posteriori, and thus casting a retrospective glance at the Italy of those years, the result produced by the culture of the time were probably ever deeper lacerations that returned to us a country even more divided than before.

The same is true from a purely art-historical perspective. It is not possible to read the developments in art between the postwar period and Sixty-Eight according to a linear perspective from Guttuso to Fontana, as the English translation of the subtitle states: too many divergences, too different and too far apart were the roads that culture traveled. How, then, to read Birth of a Nation? Not so much as a narrative faithful to its title (also because, wanting to follow the reasoning of the curator who aspires to describe “the birth of new conceptions and artistic practices that can be identified today with the maturation of a new cultural identity of our country,” one comes out without having found full and exhaustive answers), but if anything, as a mere reconnaissance of the trends in Italian art in those years: an operation that is certainly not new, since similar reviews have already been organized on many occasions, but which nonetheless has a high didactic value since, despite the fact that all the artists presented now enjoy a well-defined position in the history of art, as mentioned earlier, for a large part of the public many of them still remain distant and difficult names. A didactic value that is helped by a certain clarity of exposition in outlining the paths of individual artists or individual situations, and by the spectacular installations, with a strong scenographic impact, designed by Luigi Cupellini and Carlo Pellegrini.

|

| Hall of the exhibition Birth of a Nation |

|

| Hall of the exhibition Birth of aNation |

|

| Hall of the exhibition Birth of a Nation |

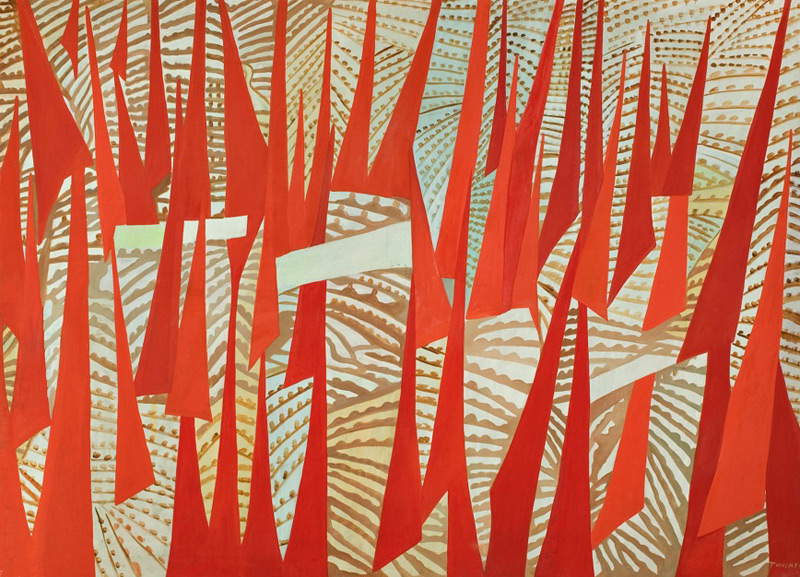

The beginning of the itinerary is entrusted to four works that establish the coordinates of the social, political and cultural temperament within which the exhibition unfolds. In 1948 the secretary of the PCI, Palmiro Togliatti, after visiting the First National Exhibition of Contemporary Art in Bologna, organized by theAlliance for the Defense of Culture (the body entrusted with supporting the cultural demands of the Popular Front), wrote in the pages of Rinascita, signing himself with the pseudonym “Roderigo di Castiglia,” a very harsh intervention that branded the exhibition as an “exhibition of horrors and nonsense.” Artists such as Guttuso, Afro, Cagli, Morlotti, Birolli, Vedova participated in the exhibition: and yet, Togliatti wondered “how one can call this stuff art, and even new art,” and went so far as to speculate that not even those who had appreciated and approved of the exhibited works actually felt “that any of the scribbles reproduced here is a work of art, but perhaps they believe that in order to appear ’men of culture’ it is necessary, in front of these things, to give oneself an air of super connoisseur and super man and to babble nonsensical phrases.” Togliatti’s pronounced zdanovism caused a deep rift among artists close to the PCI and sanctioned the beginning of a dualism that pitted realism and abstraction against each other: a dualism represented in the exhibition by the opposition between the Battaglia di Ponte dell’Ammiraglio by Renato Guttuso (Bagheria, 1911 - Rome, 1987), who, although he initially defended the aspirations of his colleagues, aligned himself with the social and popular realism that Togliatti hoped for, and the Comizio by Giulio Turcato (Mantova, 1912 - Rome, 1995), an impatient, free artist who ill tolerated dictates and constraints. The artist’s sensibility is something inescapable for Turcato and in the end, Lionello Venturi wrote, “his nature as an artist prevailed [...]. He even defended his freedom with fists in front of Cagli and Guttuso. Not that Turcato refused to deal with social themes in which he believed [...], but he represented them in abstract forms, destroyed the propagandistic efficacy, that is, in a heretical way.” On the one hand, then, Guttuso’s Garibaldian epic as an (all in all simple) metaphor for the Resistance and class struggle, and on the other Turcato’s avant-garde, free and almost libertarian yearning (Lionello Venturi himself called the Mantuan artist “anarchist enough to disobey superior orders”).

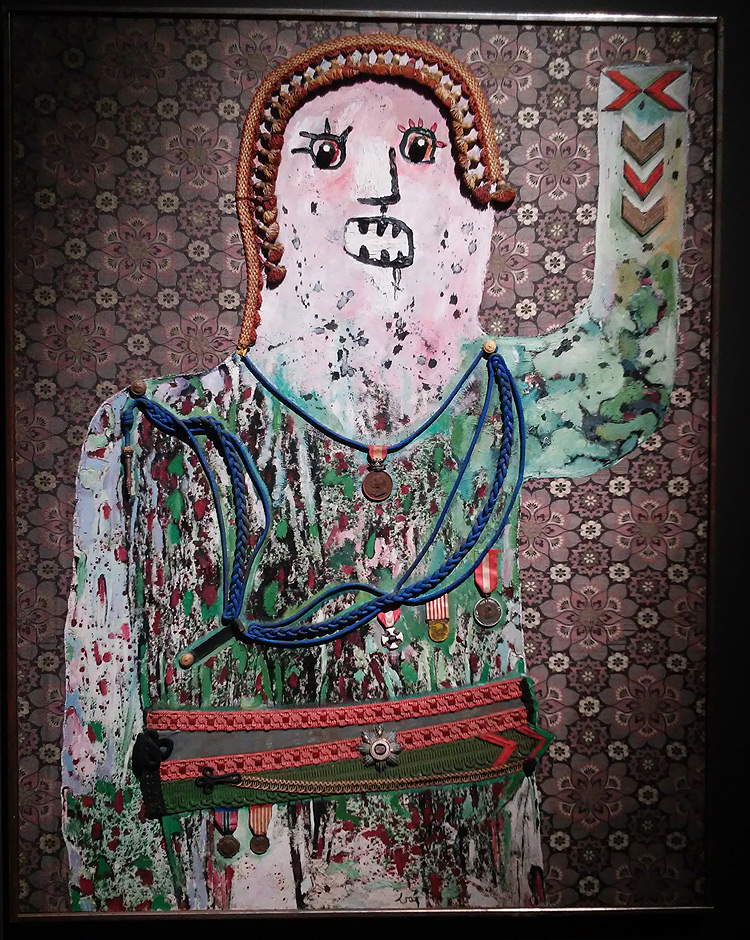

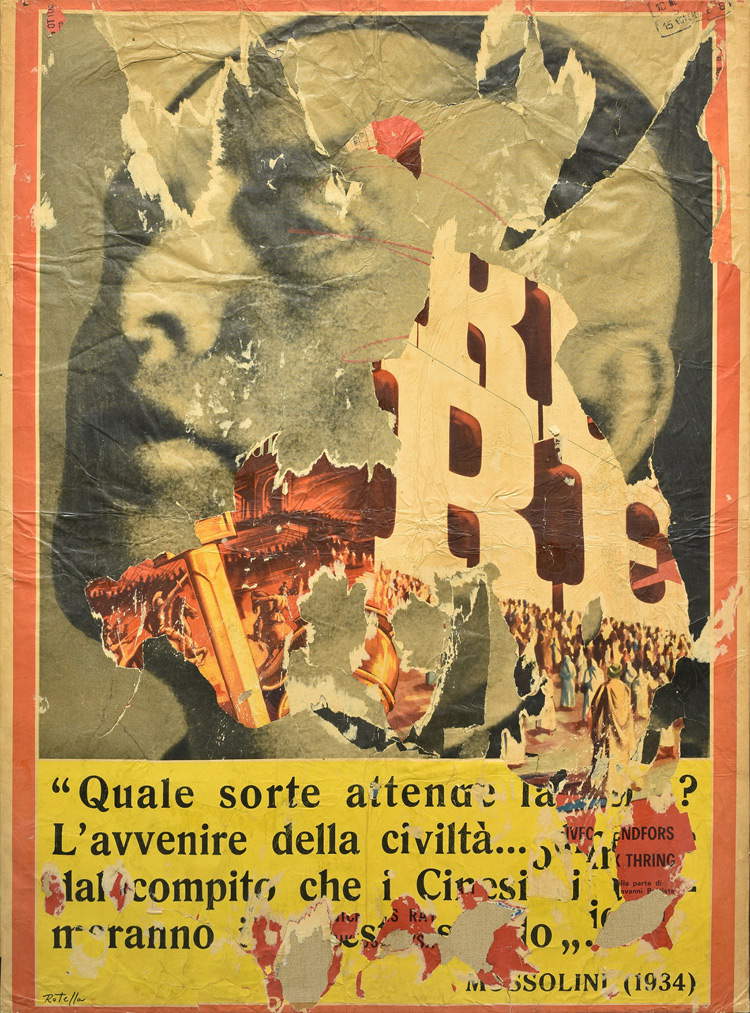

Ten years later, as the Italian and international political climate changed,political engagement already took on profoundly different contours. Hence, the other two works in the first section, General Inciting to Battle by Enrico Baj (Milan, 1924 Vergiate, 2003) and The Last of the Kings by Mimmo Rotella (Catanzaro, 1918 - Milan, 2006) fit in: Baj’s The General aims at a satirical critique of power (the general is a symbol of Cold War tensions), highlighting its most grotesque and violent aspects with a strong work of desacralization, while Rotella, with his posters filled with tears that, in the case of The Last of Kings, tear apart Mussolini’s effigy, empties the institution of the propaganda poster of content. What Rotella reproposes, Barbero writes, is the matrix of the “futurist gesture that constructs and reveals the image, instead of being a pure gesture of matter.” It was precisely the poetics of gesture that would be central to the research of Italian artists between the 1950s and 1960s: thus, the works of Alberto Burri (Città di Castello, 1915 - Nice, 1995) and Lucio Fontana (Rosario, 1899 - Comabbio, 1968), authors who made the most advanced peaks of Italian artistic research in the early 1960s, arrive punctually in the next room.

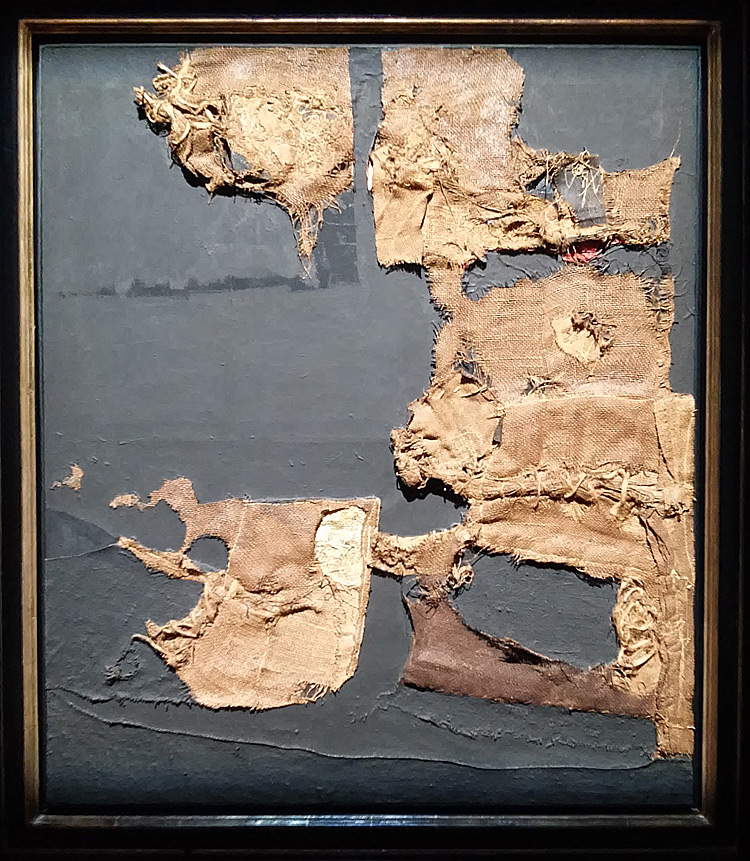

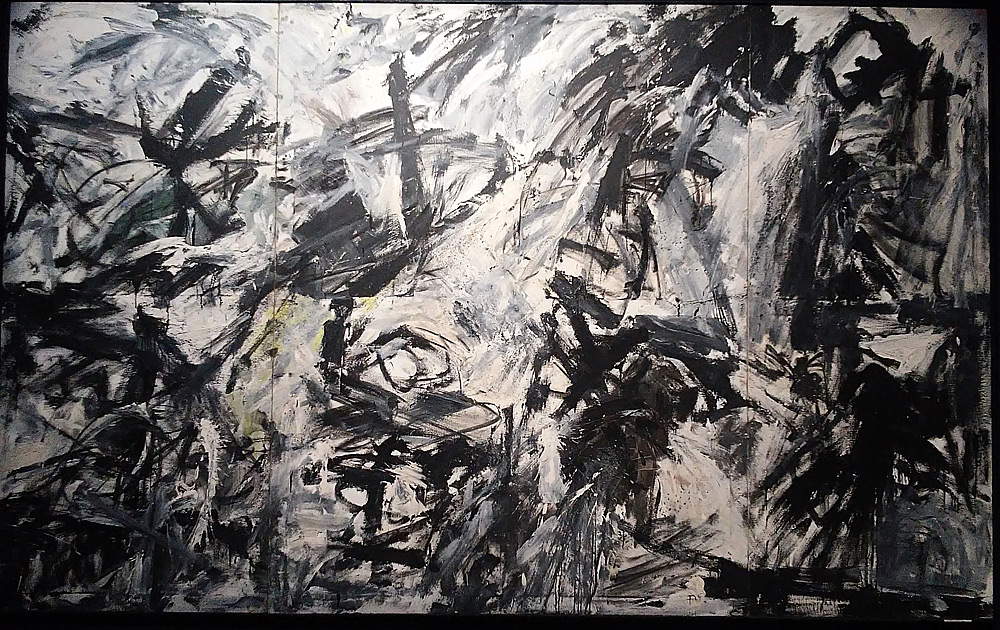

Burri started from a suffered substratum (the world conflict, imprisonment in Texas as a prisoner of war) to elaborate his poetics of matter: his sacks, at a first reading, evoke the past spent in the Hereford prison camp (where foodstuffs arrived inside jute sacks), but going deeper they can be interpreted as research on the possibilities of matter and color (Cesare Brandi argued that Burri’s works were art in the same way that Titian’s altarpieces were: Burri’s experiments are “colors, transfigured ingredients of an image no longer subject to earth’s gravitation”), and they are also, Barbero suggests, symptoms of “the desire to confront a new world through a new poetics of materials.” Burri’s sacks are thus extremely living works, a prelude to the Umbrian artist’s later research, which would lead him to experiment with an art where matter shapes itself. Gesture is possibility and openness: this is the premise of Lucio Fontana’s researches, which welcomes the visitor with the great Spatial Concept, New York 10 of 1962, a work in which Fontana’s celebrated cuts, with which the Argentine-born artist had opened new perspectives and given rise to new ways of looking at the work of art, evoke the profile of the U.S. metropolis, “more beautiful than Venice,” by the author’s own admission. The power of gesture then found another leading exponent in Emilio Vedova (Venice, 1919 - 2006), present in the exhibition with a Scontro di situazioni, and who with his furious expressionist compositions claimed, as he had to declare in a conference held in Venice in 1954 and which was part of the discussion between figurative and abstract art, the need “to redeem signs, colors, from all laziness, from all vices, for the great adventure: For the expressive birth of a new human condition.”

;

|

| Renato Guttuso, The Battle of Ponte dellAmmiraglio (1955; oil on canvas, 300 �? 500 cm; Rome, Galleria Nazionale dArte Moderna e Contemporanea) |

|

| Giulio Turcato, Comizio (1950; oil on canvas, 145 �? 200 cm; Rome, Galleria dArte Moderna) |

|

| Enrico Baj, General inciting to battle (1961; oil, collage, trimmings, decorations on fabric, 146 �? 114 cm; Private collection, Courtesy Fondazione Marconi, Milan) |

|

| Mimmo Rotella, The Last King of Kings (1961; décollage on canvas, posters, glue, 130 �? 97 cm; ahlers collection) |

|

| Alberto Burri, Sacco e oro (1953; sack, acrylic and gold on canvas, 103 �? 89.3 cm; private collection, Courtesy Galleria dello Scudo, Verona) |

|

| Lucio Fontana, Spatial Concept, New York 10 (1962; copper with lacerations and graffiti, 234 �? 282 cm; Milan, Fondazione Lucio Fontana) |

|

| Emilio Vedova, Clash of Situations 59-II-1 (1959; tempera, charcoal, and sand on canvas, 275 �? 444 cm; Venice, Fondazione Emilio and Annabianca Vedova) |

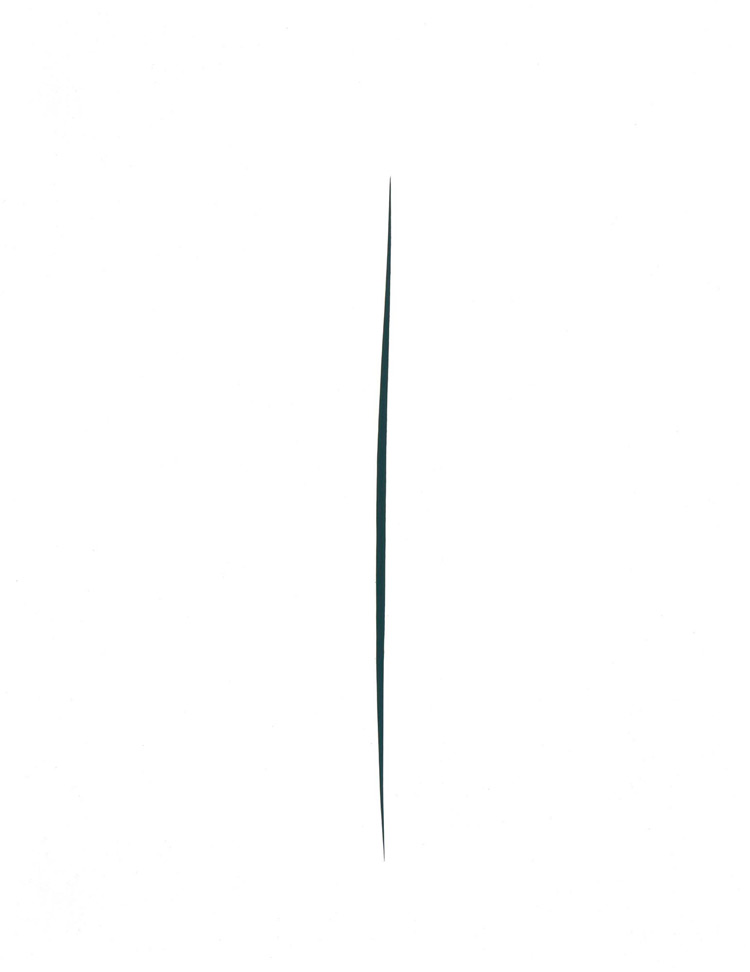

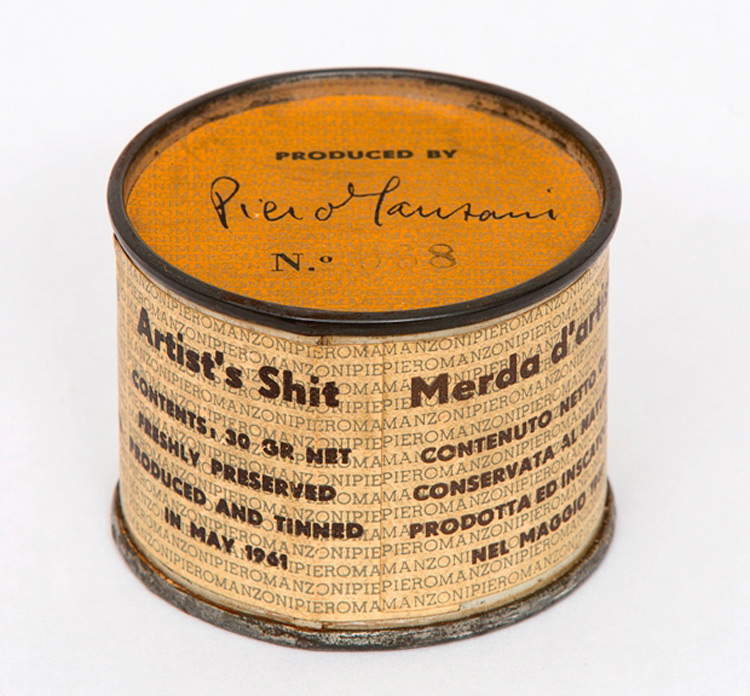

There were many artists who felt the need to bring their previous artistic experiences back to zero, without obviously seeking a zeroing out as an end in itself, but trying to open up to new possibilities: many of these researches, even divergent and contrasting ones, are exhibited in the most spectacular room of the Palazzo Strozzi exhibition, the third, with the installations recreating a large white cube space that gathers together several works by the most up-to-date artists of the early 1960s. The choice of monochrome, the curator informs us, is made with the precise choice of opening the field to experimentation that transforms the work into a concept. Monochrome, the forerunner of which was Lucio Fontana (in the room he is found welcoming the visitor with one of his 1965 Attesa, although his research on single color dates back to the late 1940s), becomes fundamental in the poetics of Piero Manzoni (Soncino, 1933 - Milan, 1963), who was the founder, together with Enrico Castellani (Castelmassa, 1930 - Celleno, 2017) of the magazine Azimut/h. It was published in only two issues, between 1959 and 1960, but its reach was disruptive: the goal of the two founders and of those who gravitated around the magazine (some names: Vincenzo Agnetti, Gillo Dorfles, Nanni Balestrini, Edoardo Sanguineti, Agostino Bonalumi, Lucio Fontana himself) was to find new modes of expression, suitable for the society of the time, such as to be able to insert Italian culture within a discourse open to international suggestions (the magazine, after all, was also looking far outside Italy) and to be able to involve the relative according to totally unprecedented optics. And so that the goal could be achieved more consistently, Azimut/h also had its own gallery, in Milan, which wanted to be called Azimut (without the final “h”) and which became a place where the most daring innovations were experimented.

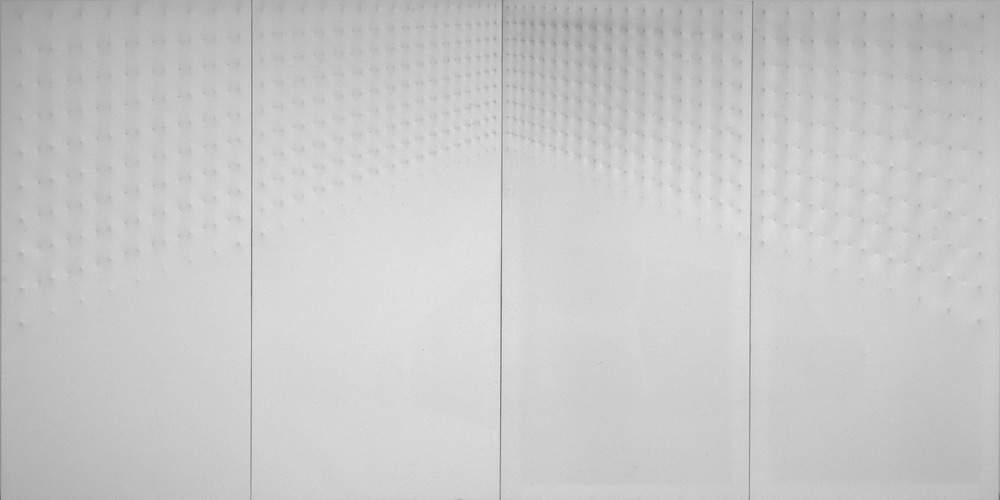

Among these were Manzoni’s Achromes, totally colorless works of art that, while referring to Burri’s materialism, distance themselves from it in that they are works that lose all allegorical connotations and return to their primordial state of objects that, devoid of any meaning, become a “field of unlimited possibilities of life,” as Germano Celant had written: and the surface of theAchrome, totally white, is for Manzoni “unique, unlimited, absolutely dynamic,” with the consequence that “infiniteness is strictly monochrome, or better yet, of no color.” A surface that, Manzoni wrote again in the first issue of Azimut/h, stands “outside of any pictorial phenomenon, of any intervention extraneous to the value of a surface”: this is the meaning of its monochromy, of the objectification of the work of art that, shortly thereafter, would lead to the celebrated Merda d’artista. The idea that a surface can be “infinite” (i.e., finite within the material boundaries of the physical support, but potentially infinitely replicable) was also the basis for the works of Enrico Castellani, who also worked, however, on three-dimensionality, fascinated by Fontana’s research: in the exhibition, the public has the opportunity to appreciate a large White Surface from 1968, where the extroversions typical of Castellani’s language compose a texture that constitutes a portion of infinity that is also repeatable and that, in its rendering the surface of the object the piece of a sequence, also succeeds in introducing the dimension of time into the work of art. Agostino Bonalumi (Vimercate, 1935 - Desio, 2013) also focused, like Castellani, on the possibility of overcoming the separation between painting and sculpture by creating canvases that took on a sculptural dimension through the insertion of protruding elements that shaped it, creating an object capable of redefining the relationship between work and space.

If the “monochromatic” room focuses mainly on what was happening in Milan, the next room investigates the Roman scene, where we witnessed the opposition between “space of the elements” and “space of the spectacle,” to refer to the coordinates already established at the time by Maurizio Calvesi and Alberto Boatto in the critical texts of the exhibition Fuoco immagine acqua terra, held at the L’Attico Gallery in Rome in 1967. On the one hand, then, the artists who were trying to reappropriate nature by introducing references to natural elements in their works of art, and manipulating everyday objects to construct a new and primordial reality at the same time: particularly significant in this sense is the Coda di cetaceo by Pino Pascali (Bari, 1935 - Rome, 1968). On the other, artists who sought ways for the relationship between viewer and work to expand to invest the surrounding space as well: an example is Michelangelo Pistoletto ’s (Biella, 1933) Dining Picture, an installation that calls the viewer to eat inside a painting. Research that anticipated arte povera, which the Palazzo Strozzi exhibition will hint at in its conclusion.

|

| Lucio Fontana, Spatial Concept. Waiting (1965; white watercolor on cut canvas, 145 �? 114 cm; Florence, Musei Civici Fiorentini Museo Novecento) |

|

| Piero Manzoni, Achrome (1959; gritted canvas and kaolin, 160 �? 130 cm; Private collection) |

|

| Piero Manzoni, Dartist Shit No. 68 (May 1961; tin box, printed paper, 4.8 �? 6.4 ø cm; Milan, Fondazione Piero Manzoni) |

|

| Enrico Castellani, White Surface (1968; acrylics and mixed media on canvas, 265 �? 532 cm; Private collection, Courtesy Fondazione Marconi, Milan) |

|

| Agostino Bonalumi, Bianco (1966; extroflexed canvas and vinyl tempera, 180 �? 257 cm; Collection Mr and Mrs Vedovi-Caprotti) |

|

| Pino Pascali, Coda di cetaceo (1966; black-painted ribbed canvas on wooden frame, 225 �? 110 �? 100 cm; Spoleto, Comune di Spoleto, Palazzo Collicola Arti Visive, Museo Carandente) |

|

| Michelangelo Pistoletto, Dining Picture (1965; wood, 200 �? 200 �? 50 cm; Biella, Cittadellarte-Fondazione Pistoletto) |

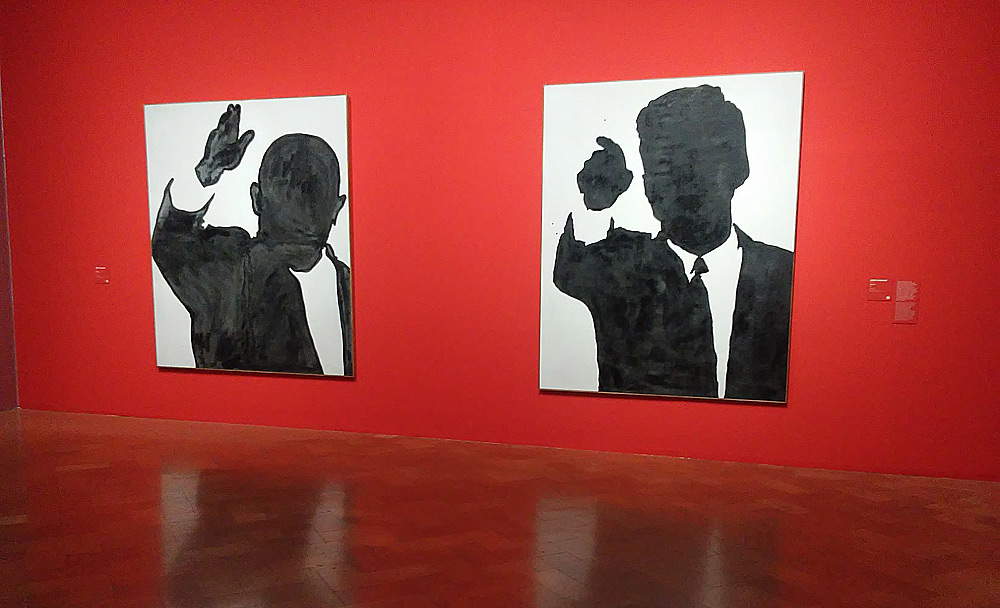

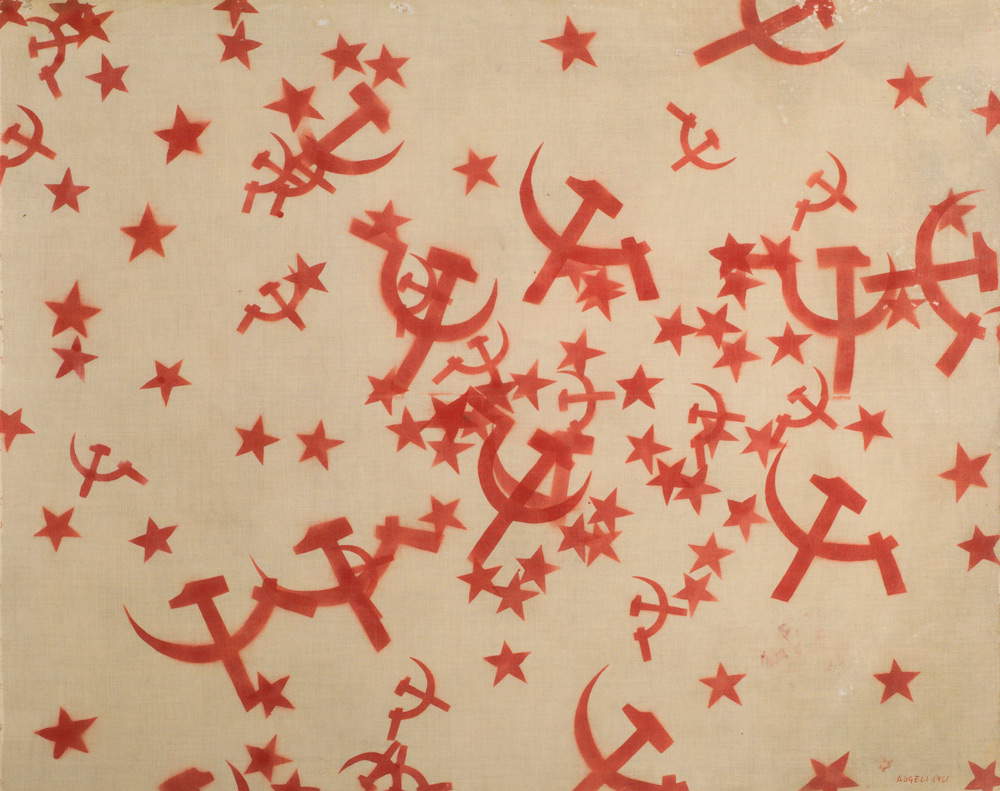

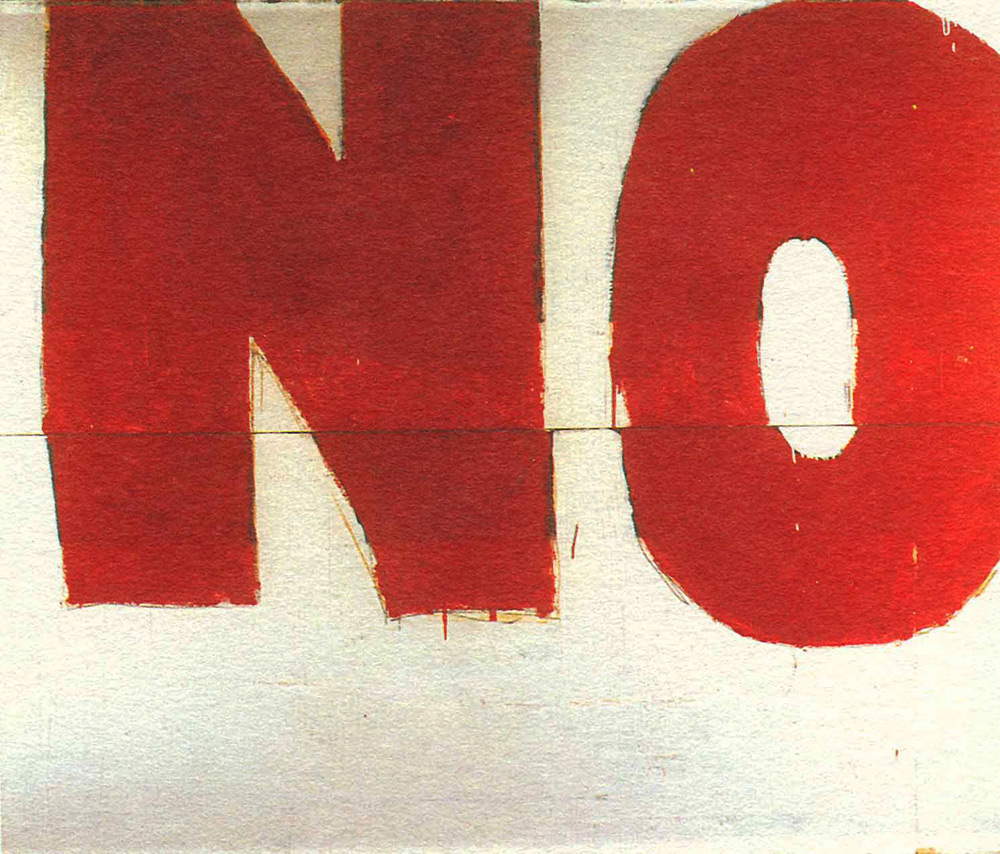

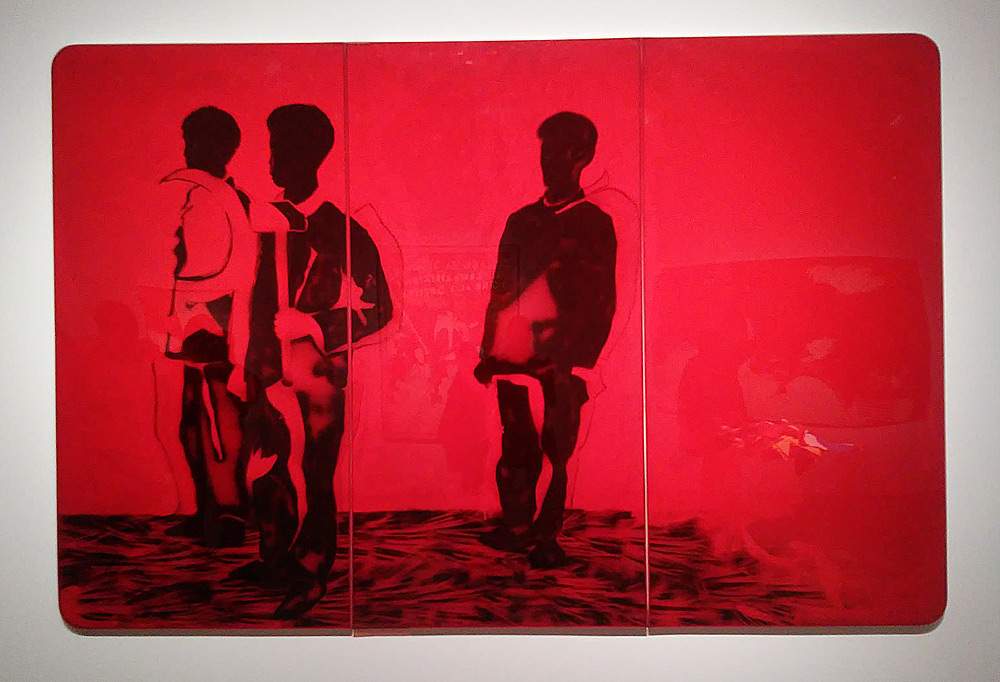

After a sort of interlude dedicated to the figure of Domenico Gnoli (Rome, 1933 - New York, 1970), the exhibition moves on to examine the evolutionary line of realism in the 1950s, which would lead to an art that “makes artists move among figures, objects, gestures, symbols, memory, chronicles and politics, in search of new images” (so Barbero and Francesca Pola in the catalog). The focus is on everyday life, politics, the media: realities that are somehow sublimated (one senses contaminations with De Chirico’s metaphysics, with abstract and conceptual research, as well as with American pop art ), as happens in the images of Kruscëv and Kennedy by Sergio Lombardo (Rome, 1939), works that transform the statesmen of the time into black silhouettes caught in iconic gestures (“gestuality,” Lombardo himself explained, “appeared to me as an archaic, innate, animal, involuntary and profound language capable of influencing and suggesting anyone, like sex, like power [...]. These black-and-white characters, these patches of gray kneaded by mechanical causes, showed the new aesthetic of industry, of mechanical printing. They were basically abstract, repetitive forms that contrasted macroscopically with the realistic oil-painted figures of the figurative painters.”) But a similar argument applies to Renato Mambor ’s Gray Men (Rome, 1936 - 2014), obvious symbols of mass society. The politicization of the language of art, which gained increasing relevance in the 1960s, is then deepened in the next room, where we move from the militancy of Franco Angeli (Rome, 1935 - 1988), an artist whose political commitment spills over into his reflections on symbols(Stars, The Beast), to the ambiguity of Mario Schifano (Homs, 1934 - Rome, 1998), whose 1960 No is an expression of protest, of the desire to break with conventions, but also of the contradictions of society. And Schifano was, however, also the artist who in 1968, with works such as Compagni compagni and Sulla giusta soluzione delle contraddizioni in seno alla società, moved on a thin thread stretched between media suggestions, pop imagery, acute irony, and intense participation in the historical moment.

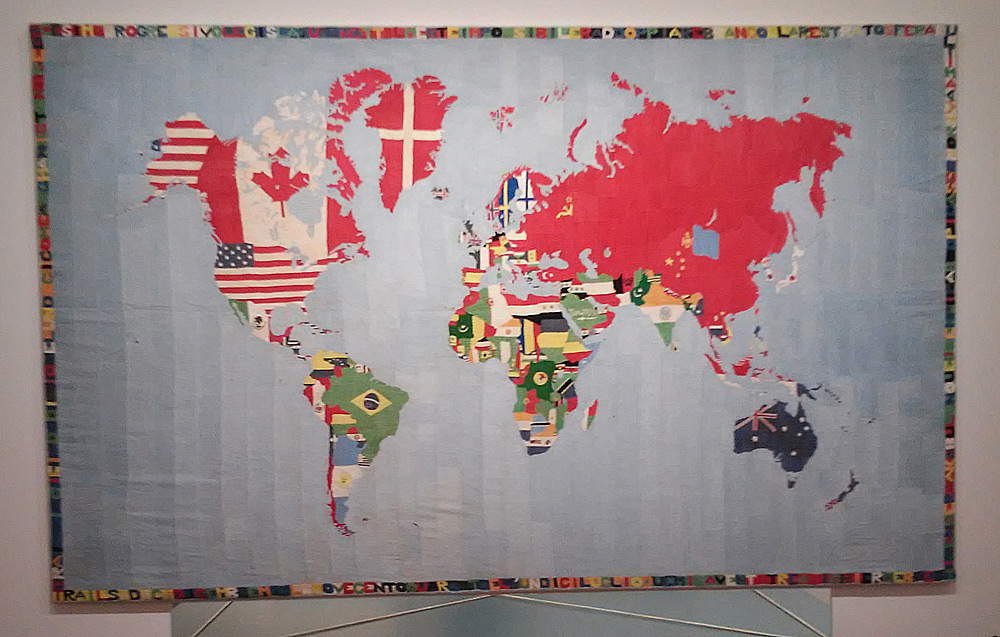

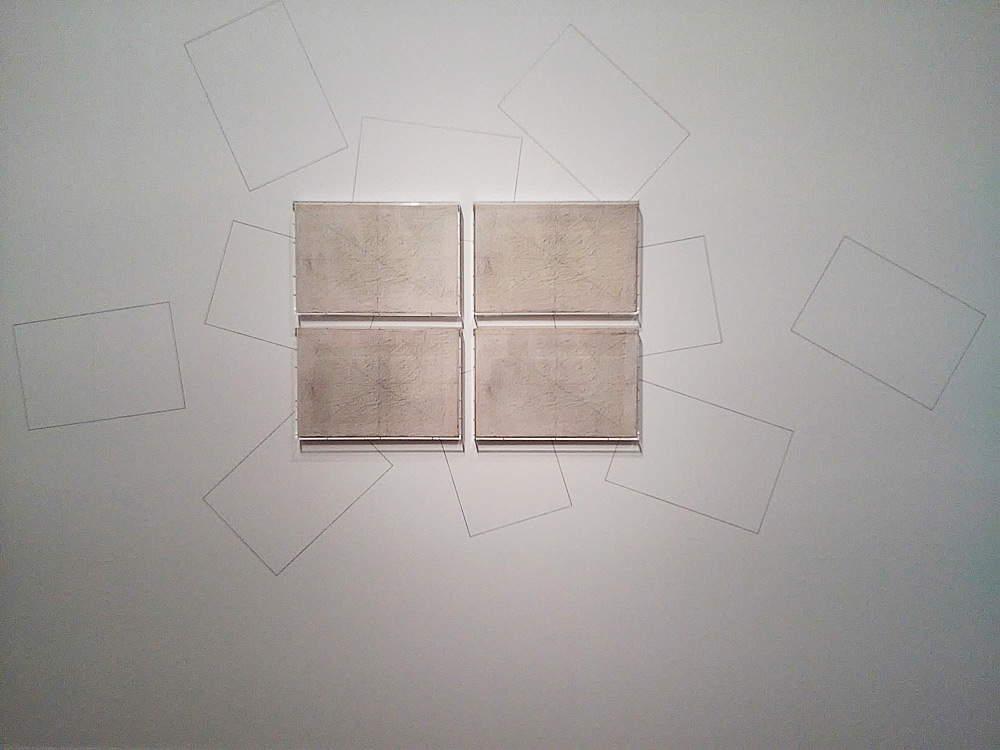

Before arriving at the last room, one passes through a couple of rooms in which one can linger on the figure of Luciano Fabro (Turin, 1936 - Milan, 2007), one of the main masters of arte povera, and perhaps the only one of the artists in the exhibition interested in a broader discourse on national identity (his Italy turned upside down and hanged, repeated and reproposed several times over the decades, is an image that almost speaks for itself), and on that of Alberto Biasi (Padua, 1937), of whom Eco is recreated, an environment, made with photosensitive panels that capture the shadows of those who approach (for the public it is certainly the most amusing moment of the exhibition), which fits somewhere between the spatial research of Fontana’s environments and the participatory culture of 1968. It is precisely the researches resulting from the culture of Sixty-eight that the last room, perhaps a little too hastily, intends to present to the public: they range from the openness to the world exemplified by Alighiero Boetti ’s Mappa (Turin, 1940 - Rome, 1994) to the reflection on culture represented by Un quadro di Giulio Paolini (Genoa, 1940), an installation composed of fourteen canvases that reproduce a work by Paolini himself, Disegno geometrico of 1960, but which is never exhibited in its entirety, and which becomes a symbol of the relationships and changes that art experiences over time. The exhibition closes with Pier Paolo Calzolari ’s (Bologna, 1943) toy train, which keeps turning around on itself ironically carrying a red flag.

|

| Sergio Lombardo, Kruscëv (1962; enamel on canvas, 223 x 190 cm; Rome, Private Collection) and Kennedy (1963; enamel on canvas, 230 x 180 cm; Rome, Private Collection) |

|

| Renato Mambor, Gray Men (1962; mixed media on canvas; 120 �? 170 cm; Patrizia and Blu Collection |

|

| Franco Angeli, Stelle (1961; mixed media on canvas with velatino, 132 �? 163 cm; Valerio De Paolis Collection) |

|

| Mario Schifano, No (1960; enamel on canvas, 160 �? 200 cm; Private Collection) |

|

| Mario Schifano, Compagni compagni (1968; enamel and spray on canvas and perspex, 200 �? 300 cm; Private Collection, Courtesy Fondazione Marconi, Milan) |

|

| Luciano Fabro, Italy (1968; iron and map, 127 �? 75 �? 4 cm; Lugano, MASI, Deposit from private collection) |

|

| Alberto Biasi, Echo (1964-1974; fluorescent canvases irradiated by Wood’s light, 364 �? 252 �? 3 cm for each panel; Padua, Alberto Biasi Archive and Gruppo N Documents) |

|

| Alighiero Boetti, Map (1971-1973; embroidery on fabric, 231 �? 373 cm; Agata Boetti) |

|

| Giulio Paolini, Un quadro (1970; photograph on emulsified canvas, 40 �? 60 cm; Turin, Fondazione Giulio e Anna Paolini. On view are four specimens supplemented with a wall drawing, designed by the artist for the occasion) |

|

| Pier Paolo Calzolari, Untitled (1968; mixed media on paper, buttons, electric train on track, 170 �? 275 �? 82 cm; Milan, Oscar Giuseppe Damiani Collection, Courtesy A arte Invernizzi, Milan) |

One leaves the exhibition without having satisfied the premise of Birth of a Nation, that is, whether it is possible to identify identity elements, traits that really allowed the birth of the nation in those years, and whether a sense of nation was really born in those years. The answer is negative, and, indeed, Sixty-Eight, with which the review closes, contributed to an even sharper crisis in the idea of nationhood, and the fractures of the time would later lead Italy to the years of lead. And if it is necessary to extract a reflection from the exhibition, what we obtain is, if anything, a thought on the contrasts and contradictions that characterized Italy at the time, as well as on the distance that we still experience today in relation to those artistic experiences, which never became part of a truly common cultural baggage in Italy: we have serious difficulties in recognizing ourselves in the works of many artists of the time (and it could not be otherwise, given that many of the experiments of the time were divisive, and many authors were simply not interested in deepening a discourse on identity and belonging).

Nor does the catalog succeed in advancing any substantial hypothesis that would further the thesis with which the exhibition was born: devoid of fact sheets and bibliography, and with no scholarly novelties, it is nonetheless a compendium (all in all easy, though not complete) of the artistic trends of the time, and well introduced by an essay by Guido Crainz summarizing the historical context of the time, and where the narrative of the exhibition narrated by the curator’s and Francesca Pola’s essays is interrupted by an interesting contribution on artistic realism in Italy between the 1940s and 1950s by Sileno Salvagnini and a concise overview by Chiara Mari on the relations between art and television (relations that the exhibition does not touch upon).

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools.

We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can

find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.