by Federico Giannini (Instagram: @federicogiannini1), published on 23/07/2016

Categories: Exhibition reviews

/ Disclaimer

Review of Andrea Aquilanti's exhibition 'Double Movement' in Carrara, June 24 to Sept. 11 at the former San Giacomo Hospital.

Article originally published on culturainrivera.it

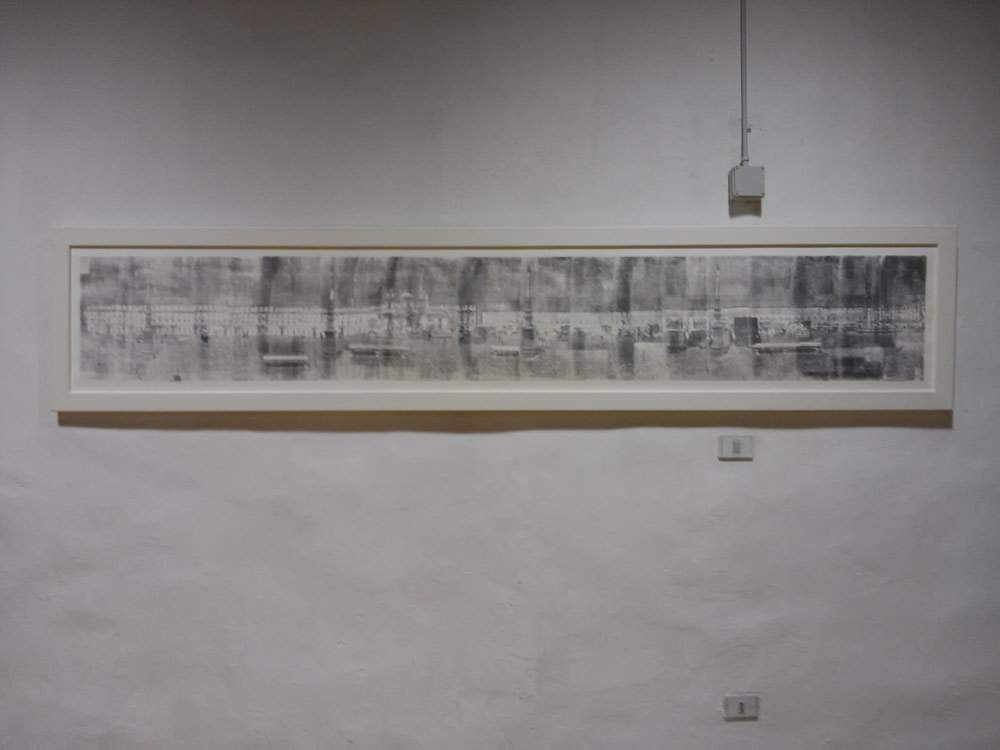

Wanting to interpret the exhibition Doppio movimento (Double Movement ), which in Carrara, in the spaces of the former San Giacomo Hospital, hosts some works by Andrea Aquilanti, we could say that the artist’s intent is to suggest to the visitor (although it is not entirely inappropriate to speak of viewer for Aquilanti’s works) that there is a bridge between the past and the contemporary, that ancient experiences can be actualized, and that a message can transcend eras. Aquilanti is accustomed to working on works that harken back to ancient art: to give just one example, his “views of Rome” (there are, moreover, two examples of these in the exhibition, on the upper floor: two plates showing the two sides of Piazza Navona to the public) are rooted in the 18th century. A direct reference, by the way, because in some views, through video projections, the artist superimposes images of Giovanni Paolo Pannini’s famous galleries on his panoramas. On other occasions, the reference was instead the imaginary prisons of Giovanni Battista Piranesi.

Speaking of Piranesi: even wandering around the main hall of the former San Giacomo Hospital immediately brings to mind the great Venetian artist, perhaps the best Italian interpreter of the Romantic sublime. Here, too, the powerful echo of Piranesi’s prisons seems to make its way. The projection that Aquilanti conceived for the Carrara setting aims to expand the space of the hall far beyond its physical limits : images of the former hospital’s own architectural structures are thus superimposed on the walls, giving the viewer the illusion of being inside an immense corridor made up of vaults and niches that, as in Piranesi, multiply as far as the eye can see. In turn, the visitor finds his image reflected on the walls to see himself now in the center of the corridor, now under a vault, now facing his enlarged shadow. Needless to mention how Piranesi, too, had inserted human figures here and there in his prisons.

Aquilanti, in short, has created a kind of mirror labyrinth made, however, of architectures: after a while, the initial amusement is almost succeeded by a sense of bewilderment, it is perceived as a kind of disorientation, first because one feels observed (other visitors will in fact see our image even if we try to hide), and then because one’s own image on the walls always takes on different dimensions and the viewer often finds himself in front of it without expecting it. Does Aquilanti perhaps intend to provide the viewer, through architecture, with a metaphor for contemporary society, that “liquid society” Bauman talks about, which has lost its points of reference and moves through a shifting present in constant transformation? Or, more simply, is it an exploration of the perception of reality and how the latter can be altered through the artist’s gesture, which can propose to his audience new ways of seeing what is around them, thus conveying a positive message that could induce the visitor to question, reflect, deepen? These are all questions that the installation at the former St. James Hospital leaves open and whose answers are up to the sensitivity of the public.

Questions that also arise in front of another work we find in the exhibition, created through mixed techniques: a reproduction of Donatello’s David against which a light is shot that casts its shadow on the wall, and next to it, on the same wall, the silhouette of the Renaissance statue, again obtained from the shadow cast on the wall, and colored with particularly garish shades. The great works of art of the past remain, but the way in which the public perceives them changes radically, and today the masterpieces of the masters who have marked the history of art seem almost like shadows of themselves, mute colored fetishes for a public to whom marketing continually subjects images of indescribable masterpieces that have ceased, however, to send messages: the public will at best be led to judge the work solely by placing it within the elementary aesthetic categories of “I like it” and “I don’t like it,” and then move on to the next masterpiece in a bulimic art binge.

Aquilanti, a well-established artist by now (last year he was present at the Venice Biennale), through this “phantasmal visual universe” that moves between “image and imagination,” “reality and representation,” “visible and invisible,” offers the Carraresi public a small sampling of his art in an exhibition that can be visited in a short time but still leaves positive feelings. Doppio movimento, curated by Lucilla Meloni, is an interesting operation for a city like Carrara perhaps accustomed to an art more tied to tradition: sure to appeal to the public, Doppio movimento makes the most of the spaces of the former Ospedale di San Giacomo, an ancient building of medieval origin, which seem almost to be the natural “set” for Aquilanti’s art. And it certainly offers Carrara, a city whose desire to question itself seems to be waning, a chance to ask itself some questions, if only to understand what kind of art we need.

Click here for exhibition info (days, times)

|

| Andrea Aquilanti, Double Movement |

|

| Andrea Aquilanti, Double Movement |

|

| Andrea Aquilanti, Double Movement |

|

| Andrea Aquilanti, Double Movement |

|

| Andrea Aquilanti, Double Movement |

|

| Andrea Aquilanti, Double movement |

|

| Andrea Aquilanti, Double movement |

|

| Andrea Aquilanti, View of Piazza Navona |

|

| Andrea Aquilanti, View of Piazza Navona (detail) |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools.

We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can

find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.