Simoninus of Trent: the "abusive saint" constructed by late 15th century propaganda to stir up anti-Semitic hatred

One might feel a sort of unpleasant embarrassment knowing that it took almost four hundred years for the Church to erase a cult that, over the centuries, has fed anti-Semitic prejudice, with the aggravating circumstance of having exploited the body of a blameless child who died, no one knows how, on Easter 1475. Almost four hundred years since the date of the beatification of poor Simonino da Trento, but four hundred and ninety if one considers that, ever since the discovery of his body, the little boy was considered a martyr of an alleged and never proven Jewish barbarism, and elected a saint by popular acclaim, although he was never canonized by the Catholic Church, despite the insistence of many: Simon Lomferdorm, the son of a Trent tanner who was found lifeless in an irrigation ditch in the city, was immediately the focus of a strong and morbid popular veneration, became blessed in 1588 and remained so until 1965, when historical research undertaken in that turn of the year ascertained that that cult was founded on nothing, and the Holy See therefore decided to suppress it.

For the first time, this gloomy affair is the protagonist of an exhibition, entitled The Invention of the Guilty. The “case” of Simonino da Trento from propaganda to history, set up in the rooms of the Tridentine Diocesan Museum and curated by the institute’s director, Domenica Primerano, with Domizio Cattoi, Lorenza Liandru and Valentina Perini: an itinerary that reconstructs the story of Simonino, the grotesque and tremendous trial that ended with the death sentences of a great many innocent people, the initiation of the mighty propaganda machine set in motion to spread the cult and exacerbate tempers against the Jews, the fortunes of Simonino in popular religiosity through the centuries, and the abrogation of the cult that closed the centuries-old affair. Today, we can brand the latter as a resounding fake that led masses of the faithful to worship what Domenica Primerano calls “an abusive saint,” malgré lui. An itinerary that combines a rigorous historical reconstruction with a careful selection of works of art, while also making engaging use of technological means that allow the audience to immerse themselves in the reality of Trent in the 15th century.

The sequence of events begins on the evening of March 23, 1475, Maundy Thursday, when Simonino does not return home and his parents report his disappearance to the authorities: two days of waiting pass, until on the 26th, Passover day, the main exponent of the Jewish community of Trent, Samuel of Nuremberg, a lender by profession, shows up at the podestà Giovanni de Salis to report the discovery of the infant’s lifeless body. Already in the preceding days, however, rumors had spread that it was the Jews who had kidnapped the child: an ancient legend, the first certain attestations of which date back to the 12th century, attributed to the Jews the custom of sacrificing, on Easter Day, Christian children forcibly taken from their parents with the aim of re-enacting the crucifixion of Christ and using the victim’s blood for ritual and healing purposes. This is the so-called Jewish ritual murder, a custom which, however, has never been historically ascertained, and which has always been branded by the most shrewd historiography as a genuine anti-Semitic invention, a folkloric myth devoid of any substance, a slanderous slander unsupported by any corroboration in reality.

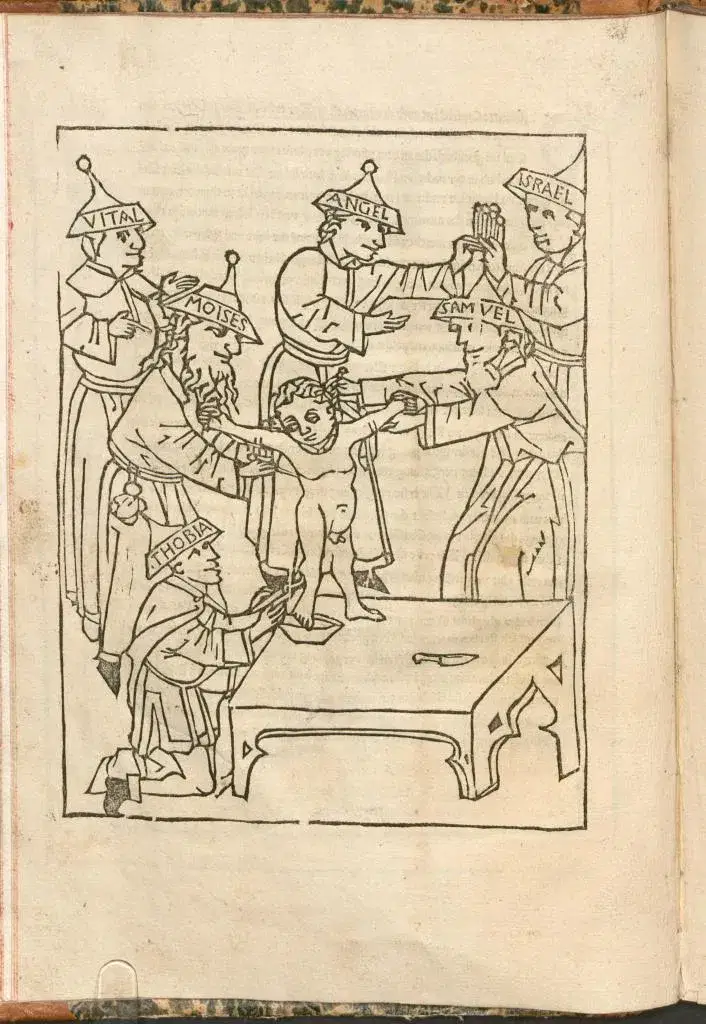

The Trent authorities of the 15th century, however, prove inclined to listen to the vox populi, so much so that Samuel of Nuremberg is taken into custody, and along with him several members of the small Jewish community of Trent end up on trial. The judicial proceedings make extensive use of the practice of torture, even beyond due process and beyond the amounts that the practices of the time prescribed (so much so that Samuel’s wife, Brunetta, will most likely die in prison as a result of the torments). The Jews on trial thus come to confess faults they do not have, going so far as to admit actions that would normally have been illogical: e.g., the concealment of the corpse in the same house as Samuel, who would later report the discovery of the body (and consider that Jews at the time lived in contact with Christians and would not have had the opportunity to commit a crime in secret), or the admission that the blood of Simoninus, i.e., of a Christian child, would have served for the salvation of the Jews’ souls (a nonsense since, noted historian Giovanni Miccoli in his 2007 article, “one would have come to recognize to that passion a salvific value, and thus, implicitly, to affirm also the truth of a fundamental point of Christian belief”). The accusatory hypothesis built on the prejudice of the so-called accusation of blood thus leads to untrue confessions, and theprocess ends with the first death sentences, handed down between June 21 and 23: Simon of Nuremberg, Angelo of Verona, Tobiah of Magdeburg, Vitale of Samuel, and Mohar of Würzburg will be burned at the stake, while for Bonaventure of Samuel and Bonaventure of Mohar, who converted to Christianity in extremis, the punishment is commuted to beheading. Instead, in November the trials against the women of the community began, lasting until 1476 and ending with the confessions of the four defendants, Anna, Bella, Sara, and Bona. The first three are forced into conversion and a promise to remain in the Christian faith (on pain of death by apostasy), while there is no news of the last.

|

| Exhibition Hall The Invention of the Guilty. The “case” of Simonino da Trento from propaganda to history |

|

| Exhibition Hall The Inventionof the Culprit. The “case” of Simonino da Trento from propaganda to history |

Up to this point, the bare narrative of the judicial chronicle and of a proceeding entirely based on the most blatant stereotypes against Jews, fueled by the insurmountable doctrinal difference between Jews and Christians and exacerbated by certain readings of the New Testament that, writes Laura Dal Prà in the catalog, ensure “stimuli to radicalize the opposition between the two faiths, with the outcome of transferring interpretations of such tenor into the illustrative apparatuses of the Gospels.” a flare-up that is “perceptible both in the physiognomic features of the Jews involved in the Gospel narrative and in the inclusion of specific iconographic details.” And it is precisely from these findings that the exhibition’s journey also begins. It is a journey into prejudice that starts with the topos of theJewish murderer of Christ, able to emerge with sharp clarity when observing the German Mair von Landshut ’sEcce Homo (documented from about 1485 to 1510), on loan from the provincial collections of the Buonconsiglio Castle in Trent: the caricatured tones with which the author depicted the Jews (the hooked noses, grizzled expressions, coarse and coarse gestures) are intended to make manifest their responsibility in the killing of Christ, while other details (the dog that often accompanies depictions of Jews, or the clothing: note the pointed cap of the figure in the center, with a scroll hanging from it, reminiscent of the tefellin, or small cases containing the words of the Torah and worn on the head by the most strictly observant Jews during morning prayer) serve to unequivocally define the religious affiliation of those who were considered the killers of Jesus.

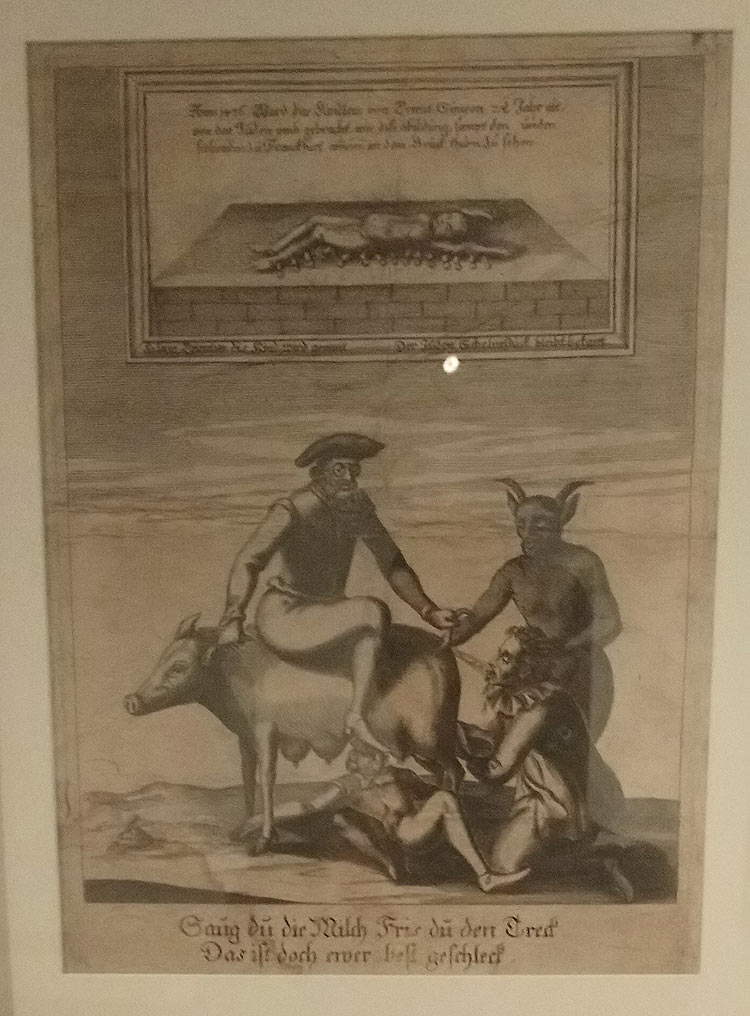

The figure of Jesus, however, is not the only one around which anti-Semitic preconceptions have arisen, and the Trentine review aims to demonstrate this by placing in the center of the room a fine Rhenish-made, 12th-century, historiated reliquary on whose surface appears a depiction of the Punishment of the Sacrilegious Jews: legend has it that some Jews who attempted to overturn the Virgin’s bier during her ascent to heaven following the dormitio were no longer able to detach their hands, losing them (they were recovered only by the prudent Jews who converted immediately: the reliquary illustrates this moment). Particularly strong is then a German print depicting one of the most violent anti-Jewish iconographies, the Judensau (“Jewish sow”), widespread in the Germanic area (the archetype is a lost late fifteenth-century fresco found on the Brückerturm in Frankfurt): the motif involves the depiction of a sow suckling some Jews, and feeding others with her own dung. Curator Lorenza Liandru, recalling the studies of historian Isaiah Shachar, traces the origins of this iconography to allegorical motifs that alluded to the vices of gluttony and lust, later reinterpreted in an anti-Jewish key on the basis of the connections and similarities between Jews and pigs found in medieval literature. An image of considerable danger, which is moreover often found linked to the accusation of ritual murder in figurative contexts where such motifs are paired.

|

| Mair von Landshut, Ecce homo (1502; Trent, Castello del Buonconsiglio) |

|

| Rhenish goldsmith, Casket Reliquary (third quarter 12th century; gilded and enameled copper, wrought iron, 32 x 44 x 15.5 cm; Trent, Museo Diocesano Tridentino, inv. 21) |

|

| German ambit, Judensau (early 17th century; Trent, University of Trent). |

This was, in essence, the climate in which a fifteenth-century Jew lived, these were the fantasies that could well oil the gears of the propaganda machine that immediately moved against Jews during and after the most acute phases of the trial of the Simonino affair: precisely the first work related to the case is exemplary not only in that it fixes an iconography that would know few variations over the centuries, but also because it well illustrates the role of the press in supporting the condemnation against the Jews and in promoting the cult of Simoninus, according to a program well orchestrated by the “director” of the whole operation, Prince-Bishop Johannes Hinderbach (Rauschenberg, 1418 - Trent, 1486), who played a preponderant role in the whole affair. Educated, charismatic, intelligent (he was among the first to realize the political potential of the press), and a skillful maneuverer, Hinderbach initiated an action that scholar Daniela Rando calls “systematic and ’scientific,’” and the first work on Simonino that one encounters in the exhibitionitinerary, the Historie von Simon zu Trient by Albrecht Kunne (Duderstadt, c. 1435 - ?, post 1520), present with a reproduction of its fourteen folios (the original incunabulum is in the Bayerische Staatsbibliothek in Munich) that tell the whole story of Simoninus, provides an interesting example of Hinderbach’s ability to put print in the service of his cause. Kunne’s Historie was printed in Trent on September 6, 1475, is a simple narrative of the succession of events (the abduction, the ritual murder, the concealment of the corpse, the discovery, the atrocious condemnations of the Jews) and was part of the dissemination strategy devised by Hinderbach, who had thought of variously addressed content: a treatise De Simone puero tridentino, drafted by John Matthias Tiberinus and intended for the educated public; Kunne’s booklet, which was instead aimed at a broader audience; and texts on legal topics that were intended to support the cause of Simoninus’ canonization in papal circles.

Hinderbach’s action also unraveled on the political level: in this sense, the tactic was to obstruct the work of the papal commissioner, the Dominican Giovanni Battista de’ Giudici, bishop of Ventimiglia, sent from Rome to investigate the proper conduct of the trial. Hinderbach welcomed him with all honors, but soon Giudici found that the whole city was against him, and he was forced to record, in reports, slanders against him, to work in an atmosphere of suspicion (the same suspicion, moreover, that he nurtured toward Hinderbach, having sensed his role in the affair: he was convinced that the witnesses at the trial were conditioned by his position), to struggle against the prince-bishop who continued to write to Rome providing numerous justifications to emphasize the regularity of the trial, and who continued to subject Giudici to strict control, so much so that the bishop of Ventimiglia had to move to Rovereto, then under the jurisdiction of Venice, to work more quietly. On June 20, 1478, a papal bull, Facit nos pietas, declared the trial regular and thus put an end to the case.

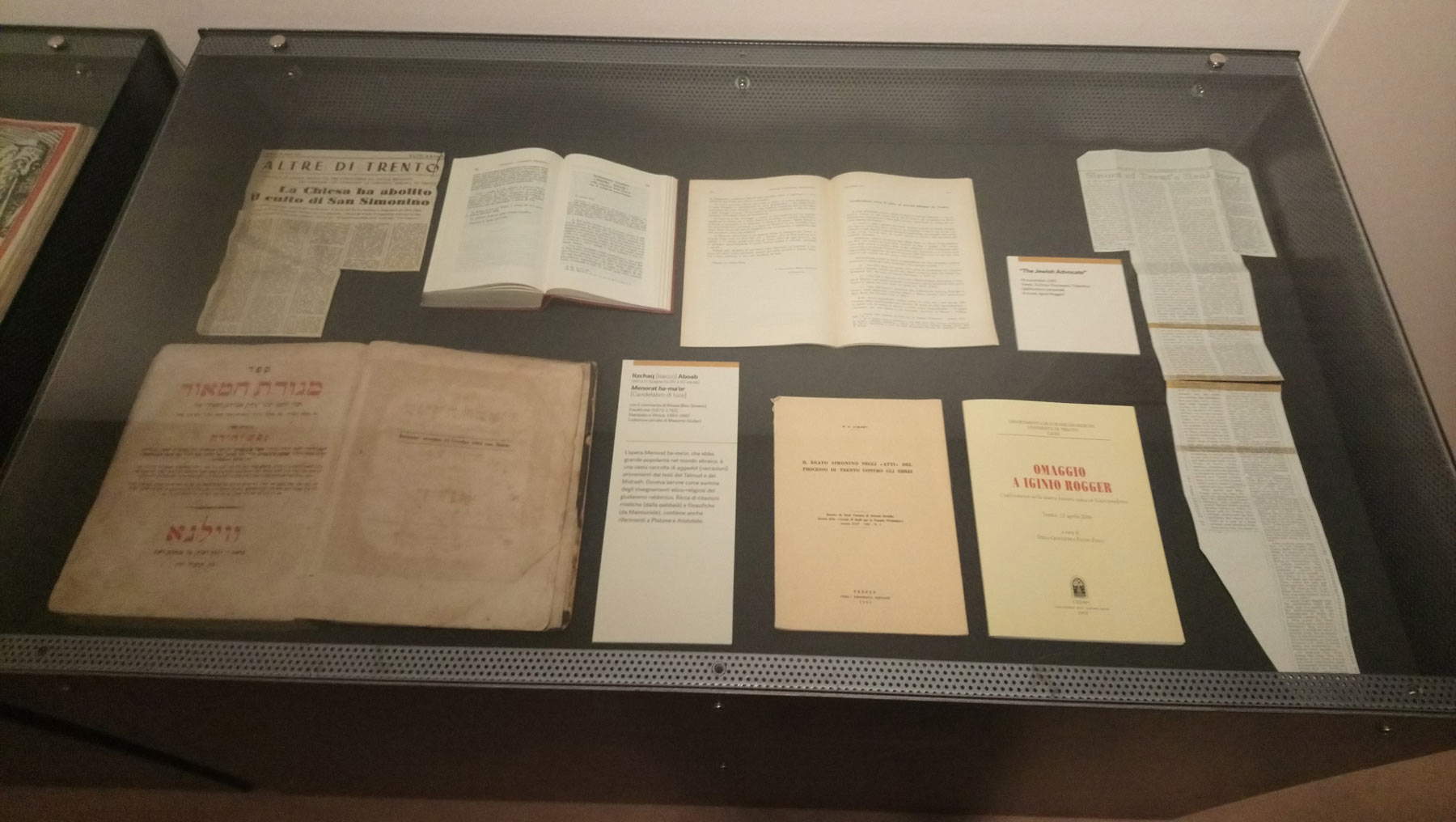

We do not know with certainty what were the reasons for so much effort on the part of the prince-bishop. It has been speculated that Hinderbach was aiming at the Jews’ property (which was actually confiscated), but the background is much more complex: “the reasons that drove Hinderbach to convince himself of the guilt of the Jewish community of Trentino and of the sanctity of little Simon,” writes scholar Matteo Fadini, “are probably unfathomable and certainly several factors (cultural, political, religious) are intertwined there.” Factors explicated in a certain way by Daniela Rando, who speaks of Hinderbach as a “bishop concerned about individual fate, inclined to read in his own calamitous times the signs of the end of the world and the arrival of the Antichrist,” but also as a man fascinated by the model of the “prelate patron of the arts, who in patronage and the celebration of ’his’ saint saw the possibility of celebrating ’his’ times and ’his’ episcopate.” For this reason we must imagine a very active Hinderbach in trying to obtain canonization for Simoninus: however, the prince-bishop did not succeed, and Simoninus was beatified only in 1588. The next section of the exhibition gives an account of the fortunes of the cult, especially in the twentieth century, and its end: liturgical objects connected with celebrations of the blessed (his reliquary, pictures of processions where the participation of children was very high: not infrequently, on these occasions in Trent children were dressed as Simonino), documents from the Italy of the racial laws in which the alleged martyrdom of the little boy of Trent is mentioned again, and finally the articles that accompanied, in the 1960s, the work of Iginio Rogger, Willehad Eckert and Gemma Volli, whose research unveiled the insubstantiality of a cult based on the outcomes of a mock trial, conditioned by prejudice, capable of extorting confessions through the reckless use of torture and arousing many doubts even among contemporaries. Eckert’s expert report, based on the trial documents, was decisive: it was sent to Rome, to the Congregation of Rites, and finally, in May 1965, the cult was abolished.

|

| Albrecht Kunne, Historie von Simon zu Trient (Geschichte des zu Trient ermordeten Christenkindes) (Trent, Sept. 6, 1475; incunable; Munich, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, 2 Inc s. a. 62) |

|

| Giuseppe Brunner, Urn of Simonino of Trent and children dressed as angels (1904; Trent, Archives of the Parish of Saints Peter and Paul) |

|

| Articles from the 1960s that followed the abolition of the cult of Simonino da Trento |

It is precisely the cult that is the protagonist of the second section of the exhibition, set up on the upper floor, introduced by an altarpiece attributed to the Austrian Michael Tanner and executed on Hinderbach’s commission, probably to decorate his funeral monument (the bishop appears there in abyss, below the figures of Saints Peter and Paul). The section focuses on the forms of Simonino’s iconography throughout the centuries: the dissemination of images was another of the cornerstones of Hinderbach’s propaganda, despite the fact that Pope Sixtus IV, as early as 1475, had sent a brief to all Italian princes to prohibit the circulation of depictions of Simonino, since the cult had not been approved by the Church. However, the large number of works dating as early as the last quarter of the fifteenth century attests with palpable clarity that the pope’s prohibitions were not respected: merit, writes Valentina Perini, to the “persuasive power of images” that was known not only to the prince-bishops, but also to the most ardent and fanatical preachers, as well as to the observant Franciscans, who in those years were active in the foundation of monti di pietà and were thus direct competitors of the Jews in the business of money lending. In the catalog, a substantial essay by Maria Giuseppina Muzzarelli identifies the Franciscan Bernardino da Feltre (the first section of the exhibition features a picture of him painted by Vicino da Ferrara) as one of the most active disseminators of the “abusive” cult of Simonino da Trento.

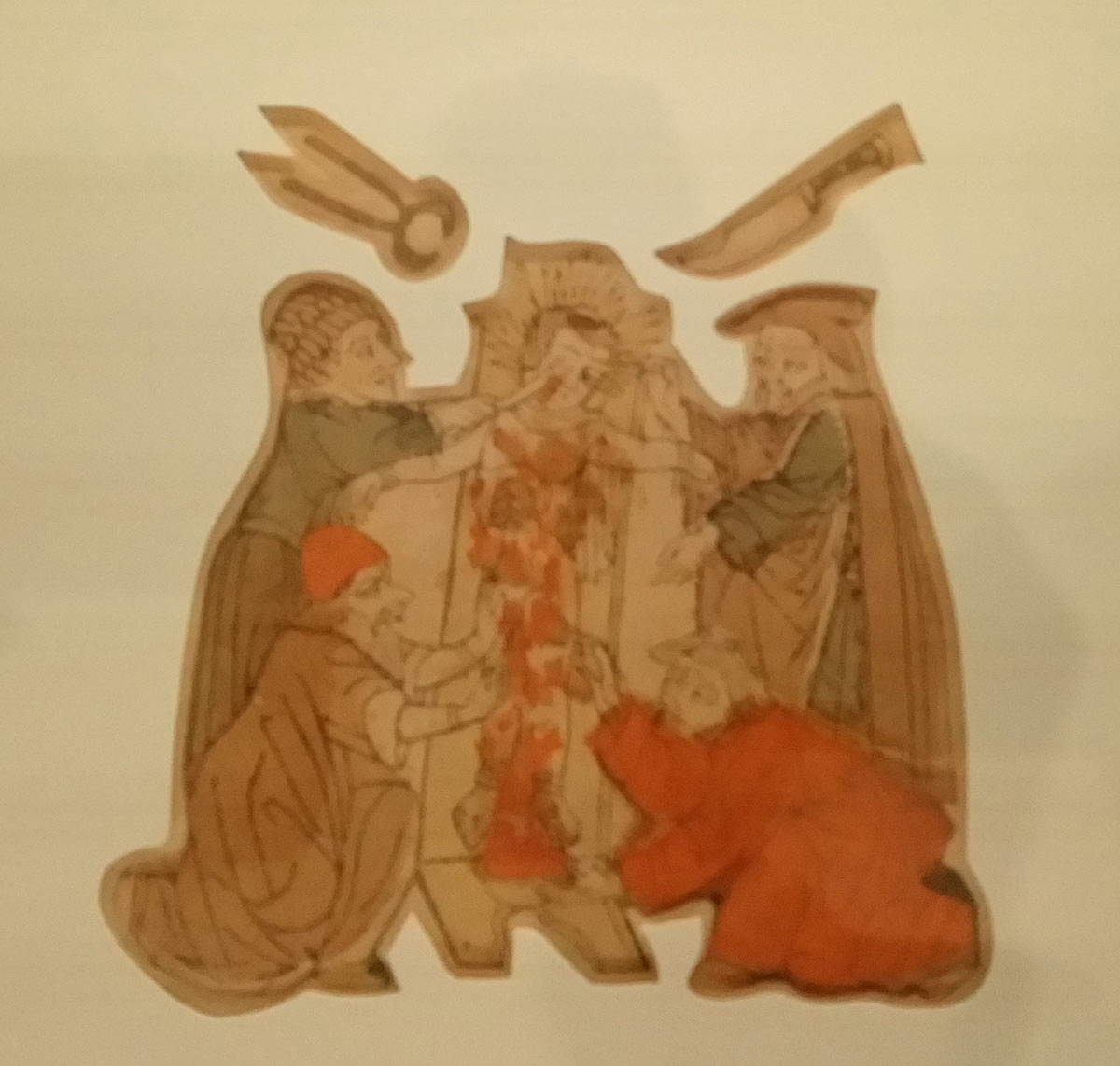

The second part of the exhibition therefore opens with a formidable and rare fifteenth-century woodcut, on loan from the Classense Library in Ravenna: these are three fragments in ancient times glued to a paper codex and anachronistically used as the frontispiece of a thirteenth-century treatise. The work passes on the best-known iconography of Simonino, that which sees him depicted in crucifixi form, recalling the sacrifice of Jesus Christ, as he is tormented by the Jews arranged at his sides, with the two at the top clasping the white scarf around his neck to strangle him (this object would later become an iconographic attribute of his) and the others applying incisions to his body in order to obtain his blood. One of the elements on which the Simonino artists would have insisted is the strong violent charge of the action, here well emphasized precisely by the blood that runs copiously down the child’s body and which the unknown xylographer has rendered with bright touches of scarlet red. A brutality that also emerges from the illustration of the martyrdom enclosed with the Liber Chronicarum by Hartmann Schedel (Nuremberg, 1440 - 1514), a German physician, humanist and collector with Italian training (he had graduated in medicine from Padua), and author of this impressive book of illustrated chronicles published in 1493: here, the action takes place inside the house of Samuel (the names of the Jews are all duly indicated) and the little boy is held in the center of the scene while he is being circumcised, with one of the future condemned to death, Angelo da Verona, collecting in a basin the stream of blood gushing from Simonino’s limbs.

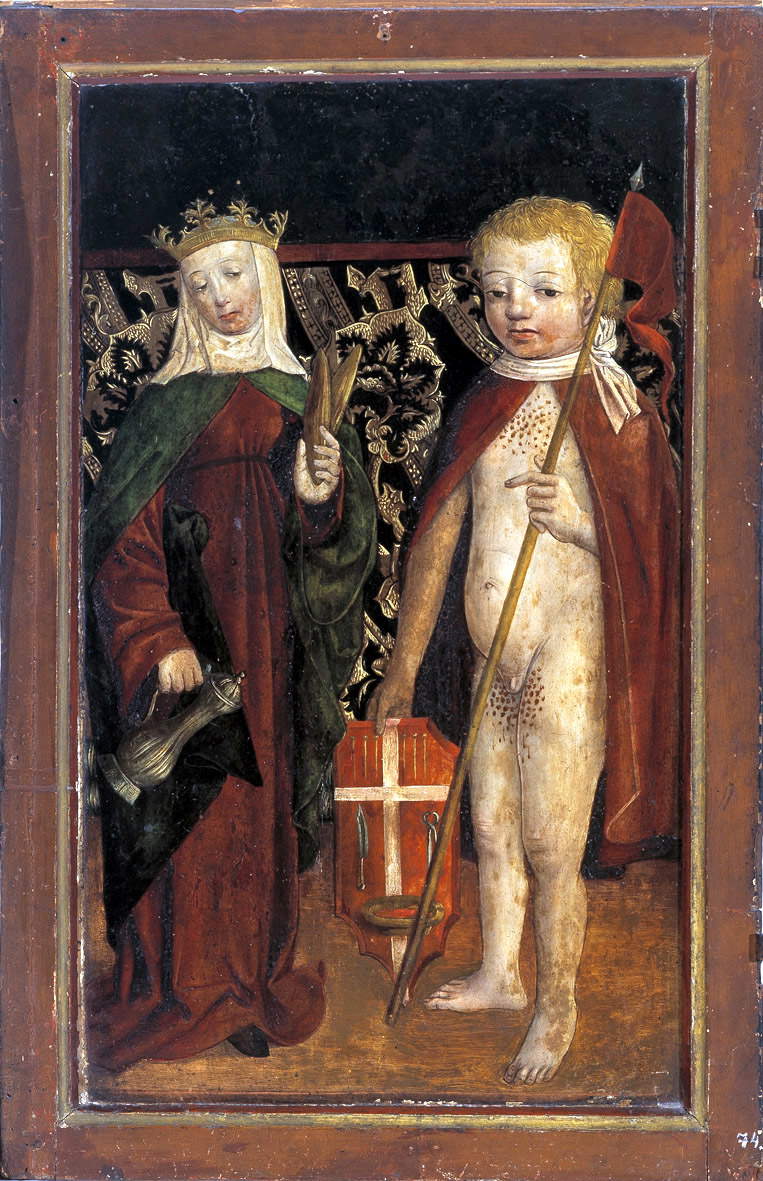

Wanting then to continue the journey among the works with a more markedly bloody and gruesome character, it is impossible not to notice the votive panel by Ludwig Klingkhamer, the work of an anonymous Tyrolean painter, where Simonino’s request for protection is a knight (whose identity is known from the inscription that runs in the lower register) caught as he returns mutilated and still bleeding from a battle against the Venetians, fought near Trent: the painting is also interesting because we glimpse in it another iconographic type, with the triumphant Simonino, capable of spreading in different contexts, on a par with the iconography of the torment that was easily popularized by the works that were observed in churches in the area. Here, Simoninus is naked, holding with one hand the shield with the signs of his “passion” (the pins, basin, knife, and tongs) and with the other the banner with the cross. It is a later type (the archetype is a lost silver statuette from 1479), but capable of spreading beyond the Trentino territory (there are attestations of it even in Umbria). The pattern was then usually completed by the scarf around the neck: this is not the case in the Klingkhamer knight’s panel, but we see Simonino painted with his attribute in a diptych that arrives on loan from Bressanone (where the little one also wears a red cloak evoking the passion of Christ), or in one of the finest 15th-century works featuring him, the triptych by Jacopo Parisati (Montagnana, documented from 1458-Padua, 1499) painted for the church of Santa Maria dei Servi in Padua, where Simonino is standing, hands folded in prayer, naked beneath the Virgin of Mercy. The painting is an eloquent witness to the spread of the cult of Simonino in the Veneto area: in the same church of the Servants of Padua there was an altar dedicated to him, although it was not the one for which Jacopo da Montagnana’s altarpiece was executed. Finally, for works of the 15th century, it is necessary to point out a unicum represented by a marble bust (not in the exhibition: there is, however, a video that complements the absence) depicting a child saint holding the palm of martyrdom and which, on the basis of traces of an ancient polychromy that would suggest bloodstains, has been recognized as a Simonino, and which on the occasion of the exhibition at the Tridentine Diocesan Museum was for the first time traced back to the Lombard sculptor Antonio Rizzo (Osteno, c. 1430 - Cesena, c. 1499) by Francesco Caglioti.

--

|

| Michael Tanner (?), Madonna Enthroned with Child between Saints Jerome, John the Baptist, Peter and Paul, Prince-Bishop Johannes Hinderbach and his chaplain (Trent, Museo Diocesano Tridentino) |

|

| Xylographer of northeastern Italy, Martyrdom of Simonino of Trent (c. 1475-1485; colored woodcut, 125 x 145 mm; Ravenna, Classense Library, inv. no. 22) |

|

| Hartmann Schedel, Liber Chronicarum (Nuremberg, Anton Kberger, December 23, 1493; Trent, Biblioteca Comunale, G 1 a 21) |

|

| Tyrolean painter (Ludwig Konraiter?), Ludwig Klingkhamer’s votive panel with the Madonna and Simonino da Trento triumphant (1487; tempera and oil on panel, 60 x 34.8 cm; Innsbruck, Prämonstratenser Chorherrenstift Wilten) |

|

| Tyrolean painters, Saint Elizabeth of Hungary and Simonino da Trento (c. 1480-1490; tempera on panel, 76.1 x 48.5 cm; Brixen, Hofburg) |

The section devoted to the sixteenth century begins with a Simonino da Trento by Altobello Melone (Cremona, 1491 - 1547), dated 1521, which shows the child standing on a pedestal, still naked, with the scarf that instead of clasping his neck is lying limply on his shoulders, and with pins in his hands: we do not know why Melone, who had no contact with Trent, made this panel (perhaps, as Marco Tanzi has speculated, the commission is attributable to the Cremonese diplomat Andrea Borgo, who, on the other hand, had interests in the city), but what is certain is that this is a Simonino of great quality and that, writes Valentina Perini, “departs from tradition by the absence, on the well-turned body, of the usual wounds,” devolving the evocation of martyrdom “to the display of two sharp punches held in the child’s hand and the needles neatly placed on the base of the pedestal.” a choice necessarily to be related to the iconography already proposed by Jacopo da Montagnana. Also from the 16th century is one of the most interesting pieces in the exhibition: it is a Lamentation over the dead body of Simonino da Trento, a carved wooden sculpture part of the ancient altar of the church of Saints Peter and Paul in Trento (from where the Martyrdom of Simonino from the Tridentine Diocesan Museum, which is displayed next to it in the exhibition, also comes from), that is, the main “temple” of the cult of Simonino in ancient times, where the chapel dedicated to the alleged martyr was located (Domizio Cattoi talks about it in a rich essay in the catalog). The Lamentation, which confronts us with an iconographic type whose desire to establish a comparison with the death of Christ is as flagrant as ever, was recognized as part of the altar (a complex machine of which only three known elements remain today) in 2012 thanks to the work of Laura Dal Prà , Giovanni Dellantonio and Valentina Perini, and the exhibition represents the sculpture’s first opportunity for public display, since it left the church in the late 19th century and has since continued to travel through private collections (it is still owned by a private individual).

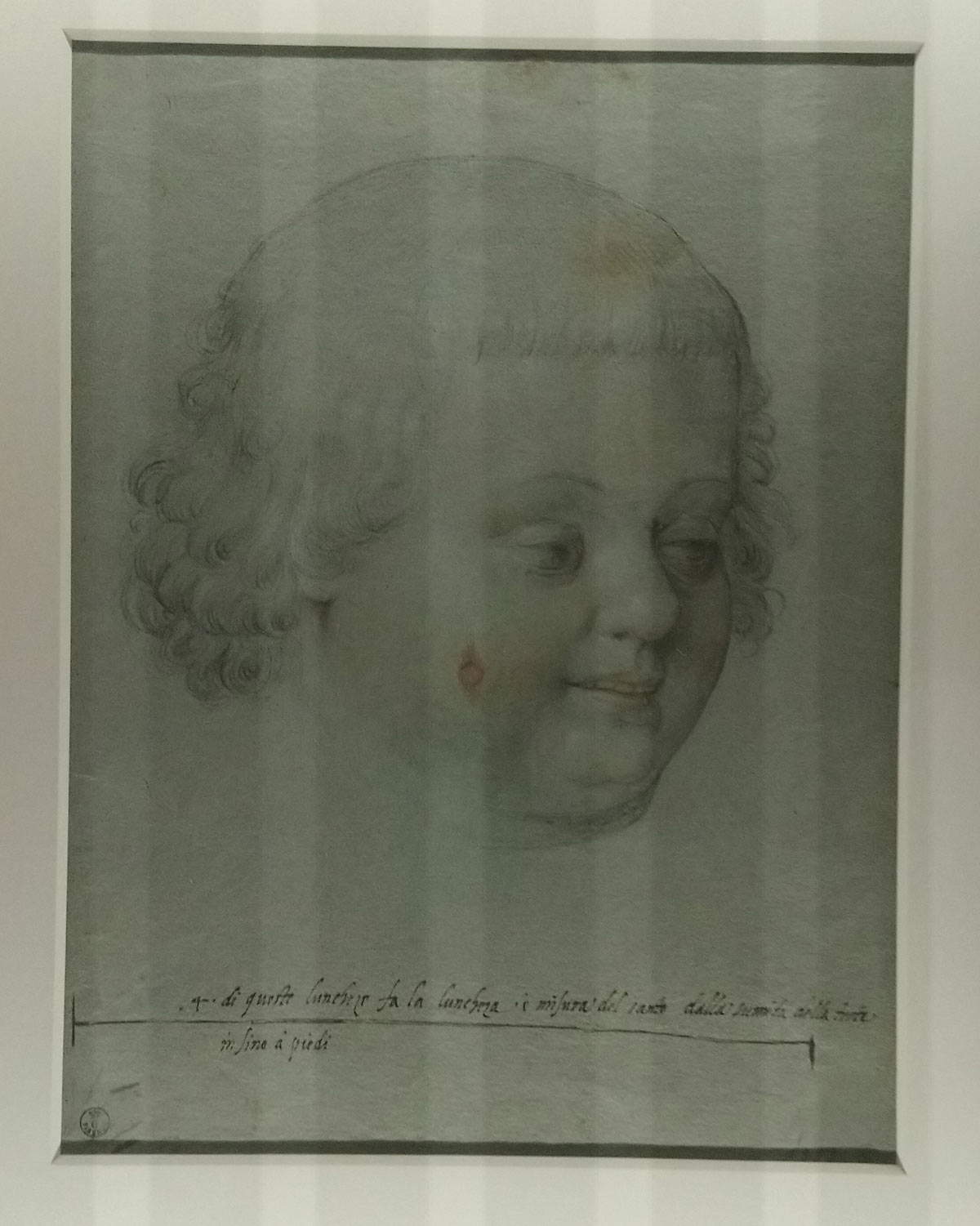

The exhibition concludes with images of Simonino that began to spread after the beatification in 1588 and the subsequent official confirmation of the cult. One of the most significant works is a Simonino da Trento with two children, by a painter from northern Italy (possibly Cremona), on loan from the Pinacoteca Nazionale in Ferrara: there we find a further iconography, which sees the child in triumph, with the usual banner, the instruments of his martyrdom (the basin, knife, tongs, scarf, and pins, which Simonino holds in his hand), and yet dressed in a red tunic cinched at the waist by a girdle, a white apron, a small ruff in the fashion of the 17th century to evoke the sash around the neck, and a pair of shoes with a bow. The two children on either side represent a unicum and, hypothesize Cattoi and Perini, who devote an essay to this iconographic variant that spread at the beginning of the seventeenth century with some texts of great relevance, could “imply a warning addressed to the faithful of young age to be wary of strangers in order to avoid the risk of sharing the fate that befell Simonino” (one of the two in fact points to the little one and the other directly addresses, with a gesture of warning, the relative). The two scholars, here, formulate the hypothesis that this iconography was popularized by some painting not known today and executed by the Veronese Jacopo Ligozzi (Verona, 1547 - Florence, 1627): in fact, we are left with one of his drawings, preserved in the Uffizi and exhibited at the Trentino exhibition, with a head of Simonino quite similar to the depictions of the infant in this new iconography.

Finally, the later works include a Martyrdom of Simonino of Trent by Giuseppe Alberti (Tesero, 1640 - Cavalese, 1716), a work from 1677 that ranks among the artist’s masterpieces as well as among the most popular images of Simonino since it was the object of adoration by the faithful on the day of the Corpus Christi procession, and the eighteenth-century processional cycle of Simonino’s stories and miracles, which on the occasion of the exhibition has had its dating slipped forward (to about 1775, a hundred years later than the chronology previously set: the restoration carried out for the exhibition was revealing). Consisting of twelve canvases, it is the richest unitary cycle dedicated to Simoninus known; it was located in the Church of Saints Peter and Paul, and was displayed in processions dedicated to the blessed: the narrative includes six different stages of the story (the counsel of the Jews, Simoninus’ abduction, torment, martyrdom, Passover celebrations, and the concealment of the corpse) and six miracles attributed to Simoninus. Although they are works of far from sublime quality, “they are of undoubted interest,” writes Maddalena Ferrari, “both for the immediacy with which they express, through the gestures and poses of the characters, the miracle that occurred from time to time, somewhat as in the case of the ex-votos, and for the setting that unites three of them, in which the sick person obtains healing right in front of the altar of Simonino, in the chapel of the same name in the church of St. Peter.”

|

| Altobello Melone, Simonino da Trento (1523; oil on panel, 98 x 47 cm; Trento, Castello del Buonconsiglio, inv. MN 1381) |

|

| Daniel Mauch’s workshop, Lamentation over the Dead Body of Simonino da Trento (first-second decade of the 16th century; carved, painted, and gilded wood, 65.5 x 61 x 12 cm; Mülheim an der Ruhr, Andrea Ohnhaus Collection) |

|

| Daniel Mauch’s workshop, Martyrdom of Simonino da Trento (first-second decade of the 16th century; carved and painted wood 81 x 110 x 24 cm; Trento, Museo Diocesano Tridentino, inv. 3016) |

|

| Northern Italian painter, Simonino da Trento with two children (early 17th century; oil on canvas, 150 x 90 cm; Ferrara, Fondazione Estense Collection, on deposit at Pinacoteca Nazionale di Ferrara) |

|

| Jacopo Ligozzi, Face of Simonino da Trento (Florence, Uffizi, Gabinetto dei Disegni e delle Stampe) |

|

| Giuseppe Alberti, Martyrdom of Simonino da Trento (1677; oil on canvas, 195 x 130 cm; Trento, Castello del Buonconsiglio, inv. MN 837) |

|

| Processional canvases with the stories and miracles of Simonino da Trento |

It should be noted that the exhibition at the Diocesan Museum of Trent is founded on decidedly modern methodological and design criteria. Alongside an itinerary built with impeccable philological rigor and which is the result of a long study work (this is demonstrated by the dense and substantial catalog, a sort of summa of the knowledge we have on the case of Simonino, both from the historical and the artistic point of view: the only flaw is that not all the works on display are catalogued), the curators have created apparatuses that make extensive use of multimedia: valuable is the “immersive” room that makes use of touchscreens to construct a narrative of the event narrated by actors impersonating the protagonists (the texts are based on the real documents of the trial), highly effective and of considerable impact are the screens that project non-stop anti-Semitic and more generally racist comments taken from real messages posted on various social networks in recent months, useful the idea of distributing to visitors, at the end of the tour or online, a questionnaire that has no scientific purpose but has proved interesting to derive data on the knowledge of Simonino’s case, the expectations of the public, and what has been drawn from the review.

And visitors showed that they caught many similarities with current events: weaving threads capable of linking the fifteenth-century story to the present was, after all, one of the curators’ goals. Many were surprised to see how the power of fake news and fakes was well known and artfully exploited even at the time (in those times the destructive capacity of artfully invented news was devastating), how propaganda, thanks to the intelligence and insights of the great manipulator, Johannes Hinderbach, made immediate use of the press invented a few years earlier in order to reach as many people as possible, how many traits of anti-Semitic sentiment have remained unchanged to the present day, how many of the bleakest pages of history have been rooted in processes of deliberate enemy-building quite similar to those that were consummated in Trent at the end of the fifteenth century.

At a time when the debate on fake news and post-truth has become central, at a time when certain politicians continue to construct myths to gain consensus, the Trent exhibition proves necessary not only to ensure a “premiere” for an affair that until now had never been addressed in a single in-depth museum study (the 1965 research re-established historical truth, a truth that is being disseminated today by the Diocesan Museum of Trent in an Italy that in recent times has experienced a resurgence of episodes of anti-Semitism), but also to cast a lenticular glance at the mechanisms of propaganda and to establish, once again, how research and correct information represent the indispensable tools for arriving at the affirmation of truth.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.