Drawings of spectacular Baroque architectural settings between Rome and Flanders

Documenting the way in which the Roman Baroque taste spread, during the seventeenth century (but also beyond) and with regard to the fields of sculpture and architecture, in the southern Netherlands, a territory corresponding roughly to today’s Belgium: we could summarize in these terms the contribution that the exhibition In the Light of Rome. The Scenographic Drawings of Flemish Sculptors and the Roman Baroque (in Rome, at theIstituto Centrale per la Grafica, curated by Charles Bossu, Wouter Bracke, Alain Jacobs, Sara Lambeau and Chiara Leporati) intends to offer in the context of a field of study that is still quite young but which has become in recent years the object of special attention from specialists, so much so that the exhibition itself is part of the broader framework of a series of researches aimed at deepening the links between Flemish sculptors and Baroque Rome. Nonetheless, it lacked, as Alain Jacobs points out in the catalog, “a beacon event to arouse and crystallize interest on an international level in a lasting way.” therefore, the best way to arouse such interest was to start precisely from Rome, with an exhibition of the highest scientific depth, capable of gathering many experts in Baroque art (the volume of contributions in the extensive catalog is impressive), of involving numerous institutions in the realization of the project, and of proposing novelties and discoveries (interesting documents on the activity of many of the artists in the exhibition were found, for example, and some unpublished drawings were exhibited and published).

|

| The first room of “In the Light of Rome” |

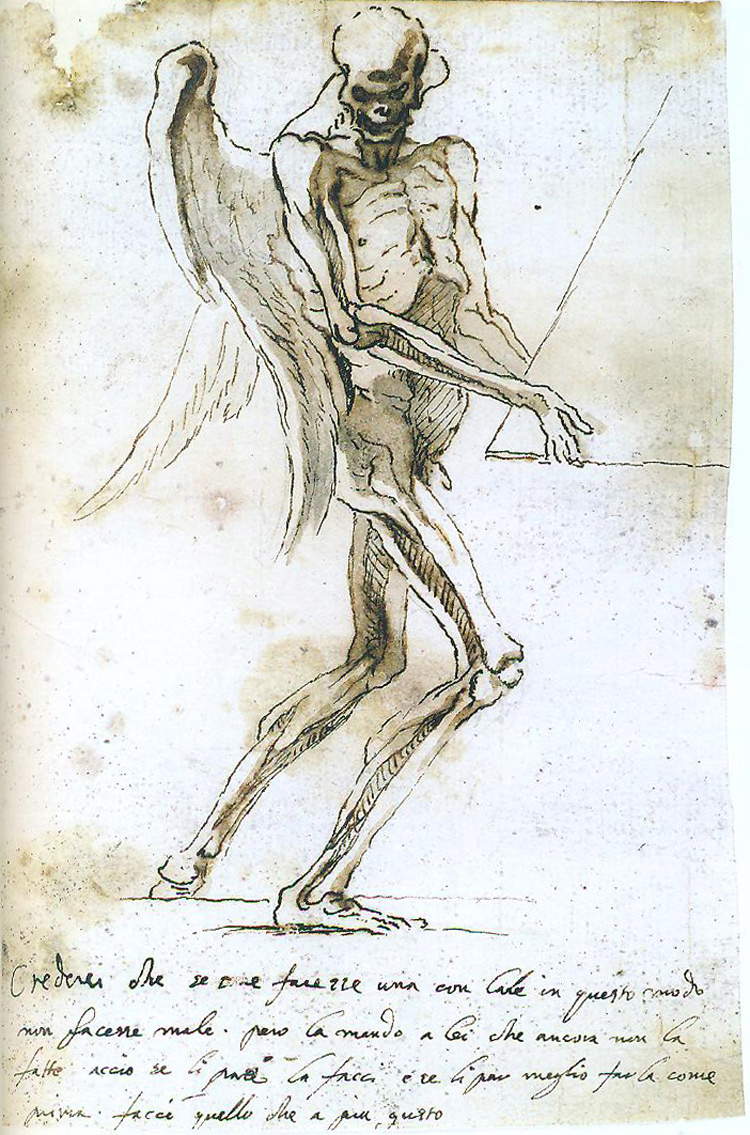

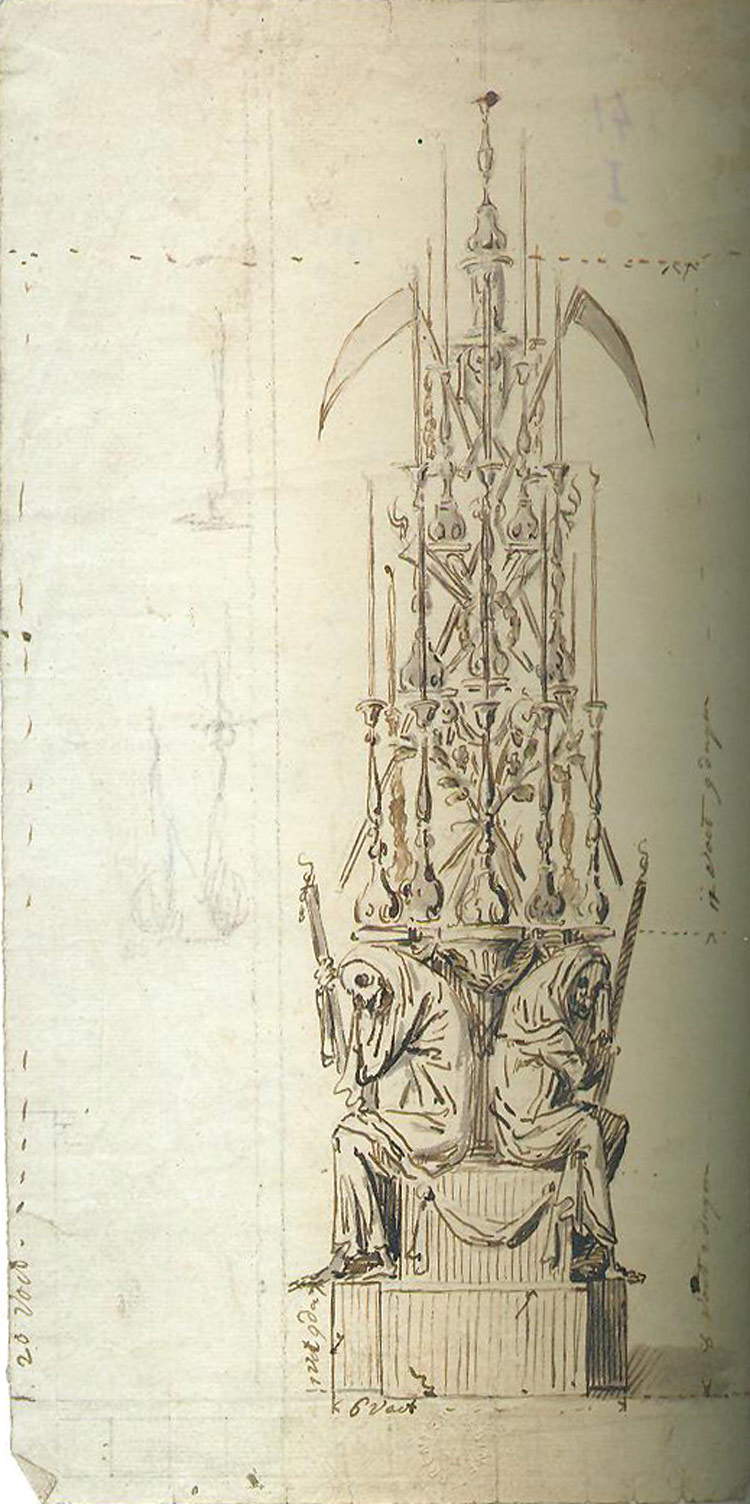

As one can easily guess from the title, this is an exhibition mainly of drawings: it is therefore not one of those exhibitions capable of exerting a particular hold on the general public. We are certainly not discovering today that exhibitions of graphic art struggle a bit to appeal to an audience other than specialists, insiders or enthusiasts. In the case of In the Light of Rome, however, the necessary elements exist for the exhibition to succeed in reaching even a wider audience: more than one hundred drawings are on display (all of the highest quality and from different institutions), there are leading names including, for example, that of Pieter Paul Rubens, whose design for the high altar of the Jesuit church in Antwerp the exhibition exhibits, and that of Gian Lorenzo Bernini, who is present with a rather unusual design (a macabre Winged Skeleton supporting a pyramid, probably a preliminary study for the catafalque erected in memory of the Duke of Beaufort in Santa Maria in Aracoeli), and above all there is a project also designed in terms of popularization. The exhibition, which occupies three rooms, is in fact divided into five thematic sections, clearly distinct but well linked by a continuous red thread (that of the interchanges between the Roman Baroque and the emerging Flemish Baroque).

|

| Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Winged Skeleton Supporting a Pyramid (1669; pen, brown ink and brown watercolor on white paper, 20 x 13.3 cm; Rome, Istituto Centrale per la Grafica) |

|

| The third room of “In the Light of Rome” |

The first of the five sections is dedicated to Baroque scenography: thus, the first room displays drawings that show how even in Flanders the apparatuses typical of Roman art of the time had been adopted. A true “Romanization” of Flemish churches that could occur thanks to two decisive circumstances. The first: the spread in Belgium of the Counter-Reformation and, consequently, of the Roman liturgy. The Netherlands, in the mid-sixteenth century, was the scene of strong religious clashes: however, we are interested to know, in particular, that in 1579 the southern provinces (those that, roughly, correspond to present-day Belgium) declared themselves faithful to Philip II of Spain and chose, in essence, to remain Catholic, with the consequence that the Tridentine rites were adopted in Flanders and that, starting in 1596, the Church established that there should be an apostolic nuncio in Brussels as well. “This process of Tridentinization of the Netherlands,” explain Ralph Dekoninck and Annick Delfosse in one of the catalog essays, “helped reinforce the inherently Catholic identity that the southern provinces had forged as a reaction to the Calvinist claims of the north.” The second circumstance that favored the spread of “Romanization” was, on the other hand, the opportunity that a large group of artists, coming from all the Flemish cities, had to stay in Rome: the artists, in contact with the impressive novelties of local art, ended up adapting their style to the new instances. And this flourishing of sumptuous and scenic altars devoted to rhetoric and spectacularity is adequately witnessed by the folios displayed in the first room.

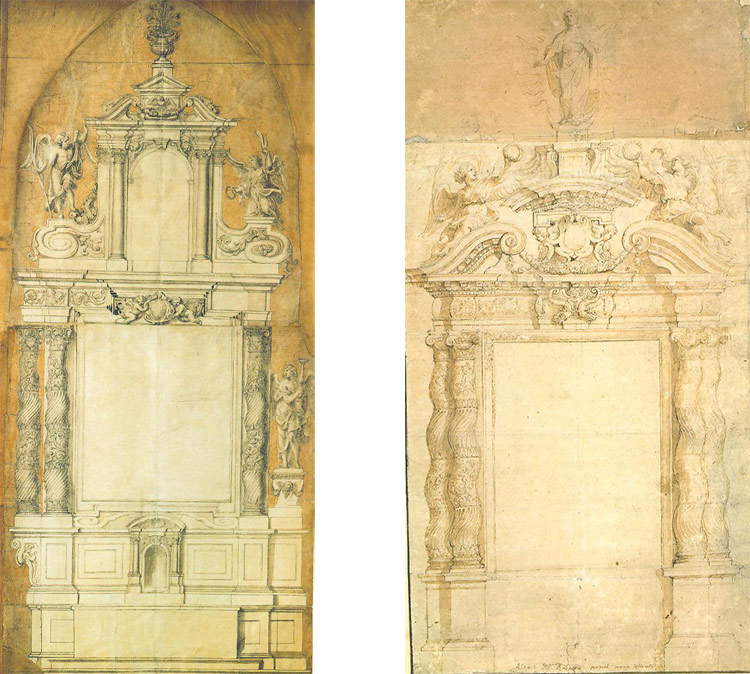

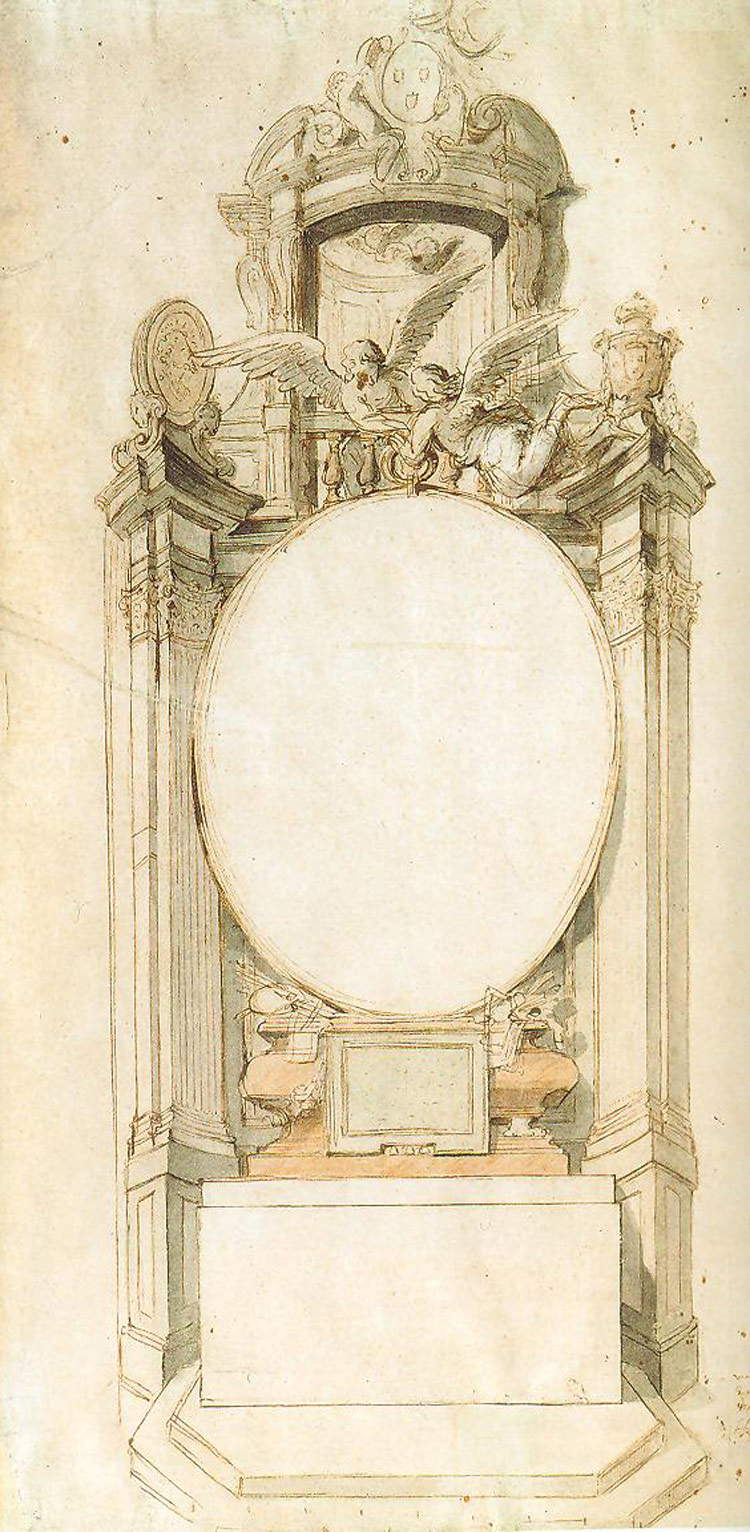

Among the first Flemish artists to sojourn in Italy was Pieter Huyssens (Bruges, 1577 - 1637): his Project for the high altar of the Jesuit church in Antwerp, compared with the homologous sheet by Rubens quoted just above (although neither was later followed in the final execution), highlights what characteristics of the Roman Baroque entered fully into Flemish figurative culture as well. Broken pediments, arched volutes, twisted columns, entablatures with recesses: the same exuberant lexicon of Roman buildings of worship. The examples are numerous: an Interior of a Church with a Monument by Hendrik Frans Verbrugghen (Antwerp, 1654 - 1724) proposes a typically Roman type of monument, that inserted in a large niche (echoing, for example, those of St. Peter’s Basilica), totally alien to the culture of the Flemish Netherlands, and again by Verbrugghen a Project for the altar and decoration of the Jesuit church in Utrecht unmistakably recalls, with its ceiling illusionistically opening onto a divine vision, the vault of the Church of the Jesus frescoed by Baciccio, and yet another sheet by the same Verbrugghen, a Project for the altar of the guild of St. Luke in the Cathedral of Our Lady in Antwerp, is inspired by Bernini’s Fonseca Chapel in San Lorenzo in Lucina in Rome.

|

| Left: Pieter Huyssens, Project for the High Altar of the Jesuit Church in Antwerp (1621; black stone, pen and watercolor black ink, sanguine on various assembled paper fragments, 110 x 52.5 cm; Antwerp, Plantin-Moretusmuseum, Prints Cabinet). Right: Pieter Paul Rubens, Project for the High Altar of the Jesuit Church in Antwerp (1621; pencil, pen and brown ink on paper, 51.9 x 26.1 cm; Vienna, Graphische Sammlung Albertina) |

|

| Hendrik Frans Verbrugghen, Plan for the altar and decoration of the Jesuit church in Utrecht (1701; pen and brown watercolor on paper, 20.7 x 16.7 cm; Antwerp, Plantin-Moretusmuseum, Prints Cabinet) |

|

| Hendrik Frans Verbrugghen, Design for the Altar of the Guild of St. Luke in the Cathedral of Our Lady in Antwerp (pen and brown and gray watercolor ink and brown watercolor on paper, 55.2 x 30.9 cm; Antwerp, Plantin-Moretusmuseum, Prints Cabinet) |

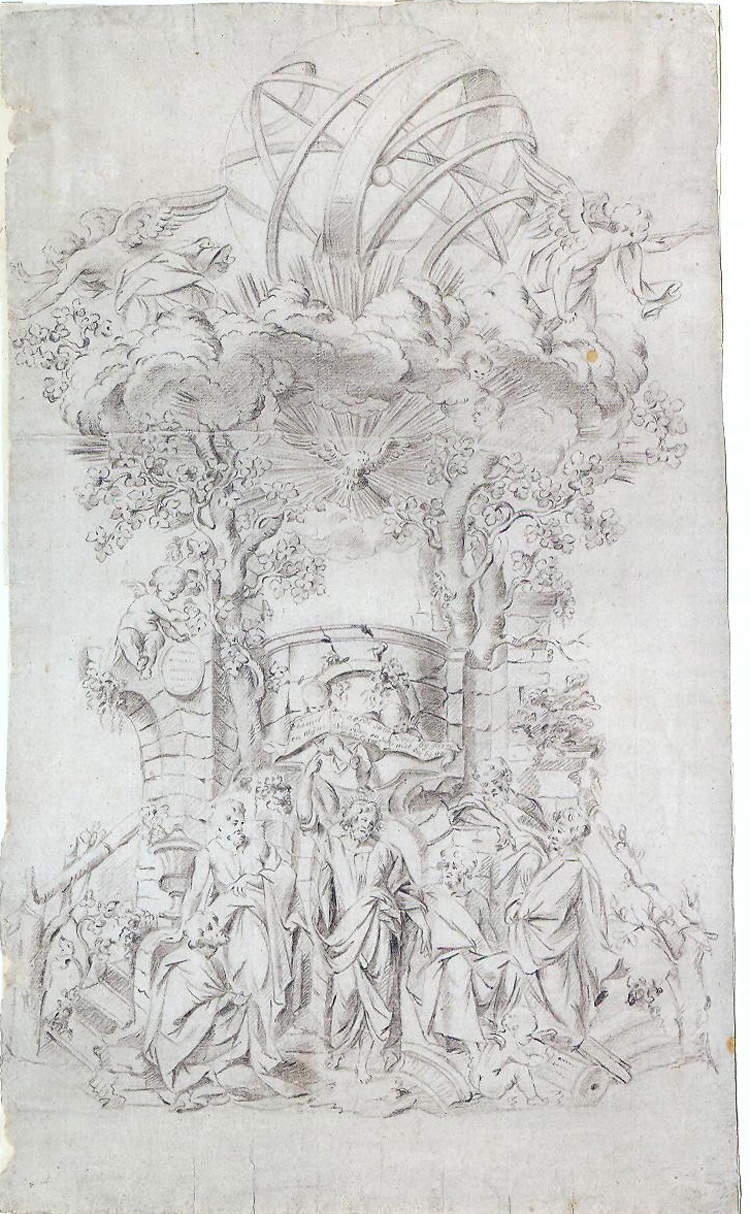

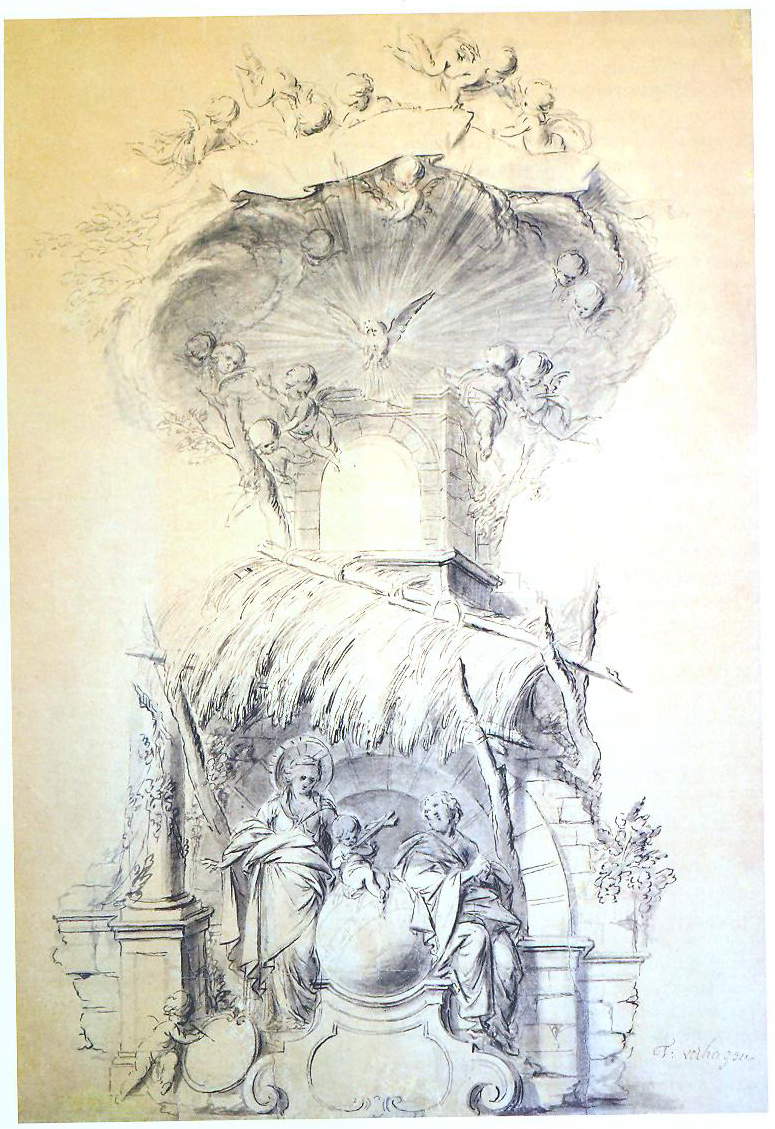

All of these elements would later be elaborated into imaginative solutions used for what were probably the two main elements of Flemish churches: pulpits and confessionals, for which Flemish sculptors devised solutions that, as far as strangeness and imagination were concerned, often went far beyond the limits set by Italian artists. The reason for this is quickly said: the pulpit, an element on which the priest was required to climb to address his sermon to the faithful, with a striking scenic apparatus would corroborate the priest’s message, which had to come through loud and clear in an area that, unlike Italy, was in constant and close contact with Reformed instances, from which Catholics had to be kept well away. The same is true of confessionals: the sacrament of penance (or “confession”) is absent in Protestant Christianity, and showing the faithful magnificent and pompous confessionals meant affirming the power of the Catholic Church. The second section of the exhibition (which occupies the entire second room) displays in sequence three incredible studies by Theodoor Verhaegen (Malines, 1700 - 1759) that show us how far the bizarreness of certain sculptors could go: the design for the pulpit of St. Catherine’s Church in Malines is imagined as a ruined architecture, covered by a thatched roof under which a sculptural group depicting the Holy Family finds a home and above which a large cloud surrounded by angels and cherubs escorts the appearance of the Holy Spirit who spreads light everywhere. Also impressive is the design for a pulpit with Jesus teaching the apostles, a kind of architecture in the form of a grove on which towers an armillary sphere accompanied by two angels and below which we notice the statue of Christ preaching together with the apostles arranging themselves around him.

|

| Theodoor Verhaegen, Project for the pulpit of St. Catherine’s Church in Malines (pen and black ink and gray watercolor on paper, 68.2 x 43 cm; Antwerp, Plantin-Moretusmuseum, Prints Cabinet) |

|

| Theodoor Verhaegen, Project for a Pulpit with Jesus Teaching the Apostles (pen and black ink and gray watercolor on paper, 56.3 x 33.4 cm; Antwerp, Plantin-Moretusmuseum, Prints Cabinet) |

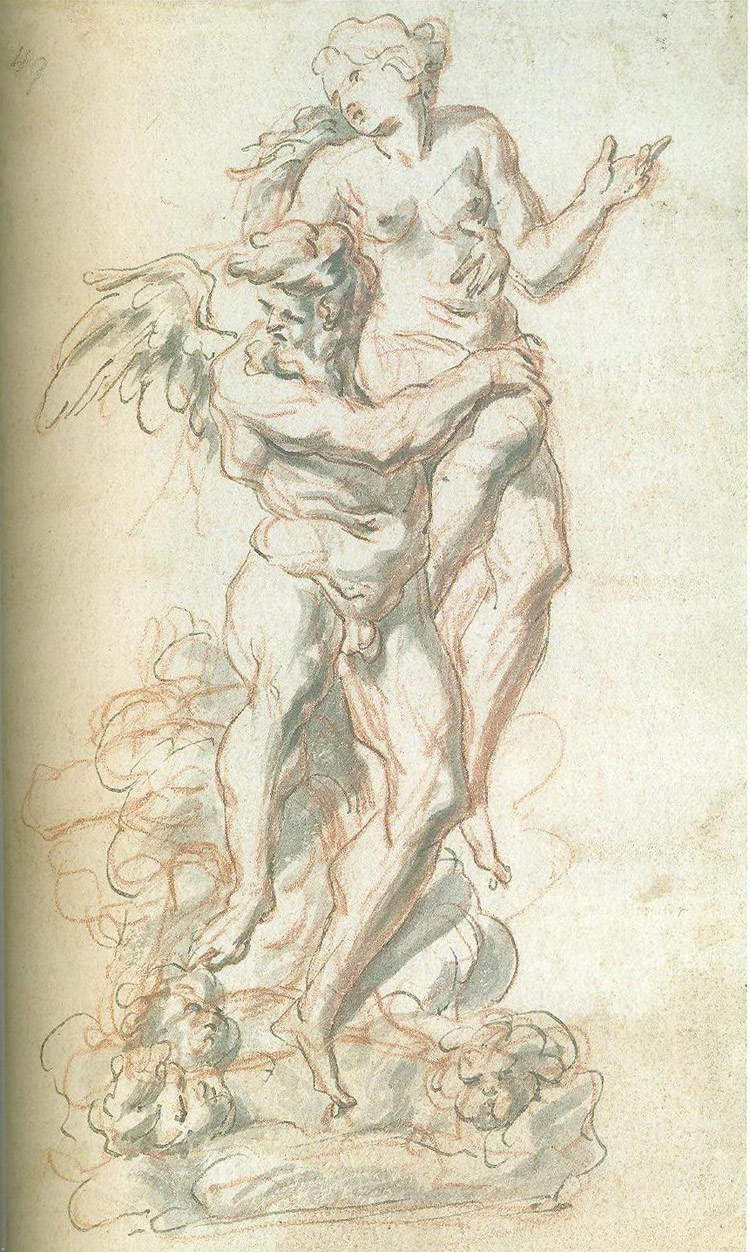

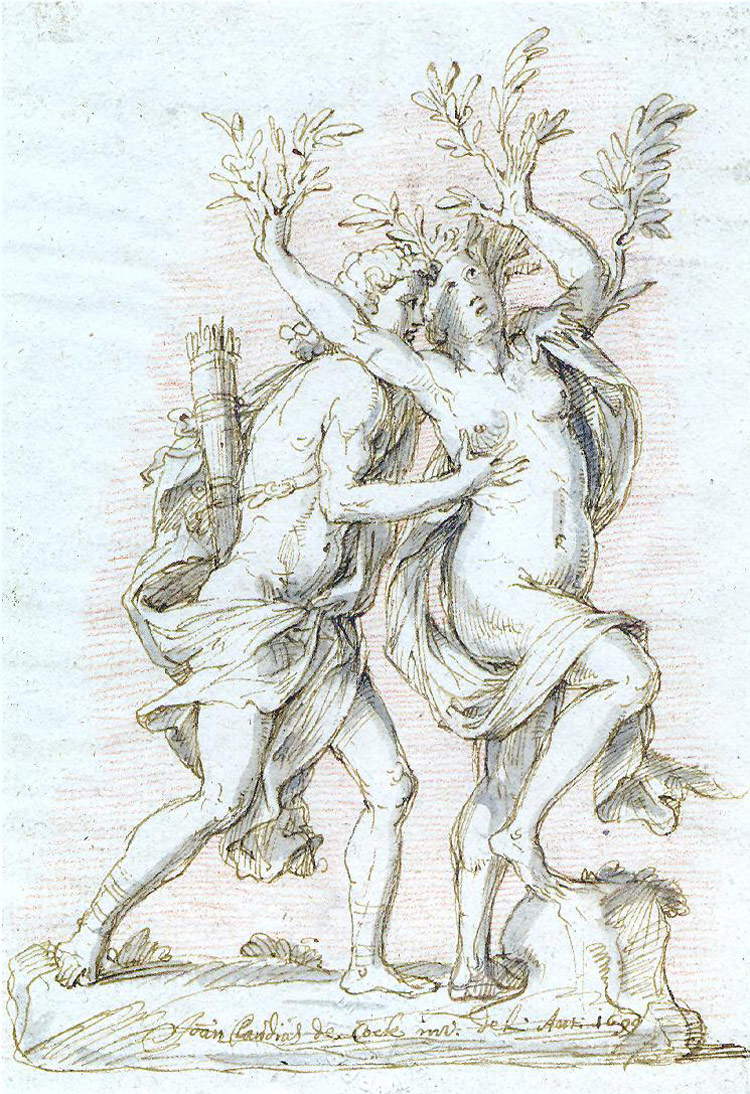

The relationships between Flemish and Italian sculptors are also investigated by a conspicuous series of studies that artists from Flanders derived by analyzing the works of their Italian colleagues. This continuous work of analysis enabled the Flemings to decisively update their art, abandoning the “hieraticism inherited from Nordic Mannerism in favor of a more naturalistic interpretation in the rendering of the human body and the rhythmic arrangement of movements.” Interestingly, the artists had come to their knowledge of Italian art in two ways: by staying directly in Italy, or by studying drawings and engravings by artists who had been to Italy. To the first case belong artists such as Robert Henrard (Dinant, c. 1615 - Liège 1676), who is featured in the exhibition with an interesting drawing copying François Duquesnoy’s Saint Andrew, one of the first (as well as perhaps the most famous) of the Flemish sculptors who sojourned in Italy, or Pieter I Verbruggen (1615 - Antwerp, 1686) whose composition for a group depicting Borea and Orizia echoes Bernini’s Rape of Proserpine. The second group includes, in addition to Hendrik Frans Verbrugghen mentioned at length above (who was never in Italy but, paradoxically, became one of the most “Italian” Flemings), Jan Claudius de Cock (Brussels, 1667 - Antwerp, 1735), who is present in the exhibition with an Apollo and Daphne inspired, again, clearly by Bernini (de Cock studied the famous group now in the Galleria Borghese on engravings).

|

| Pieter I Verbruggen, Borea and Orizia (pencil, pen and black ink, gray watercolor and sanguine on paper, 21.6 x 13.5 cm; Antwerp, Plantin-Moretusmuseum, Prints Cabinet) |

|

| Jan Claudius de Cock, Apollo and Daphne (1699; pen and brown ink and sanguine on paper, 17.5 x 15.3 cm; Antwerp, Plantin-Moretusmuseum, Prints Cabinet) |

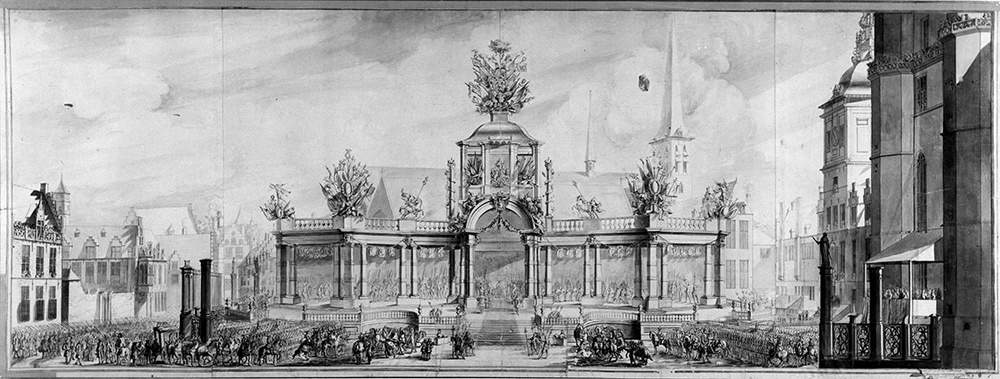

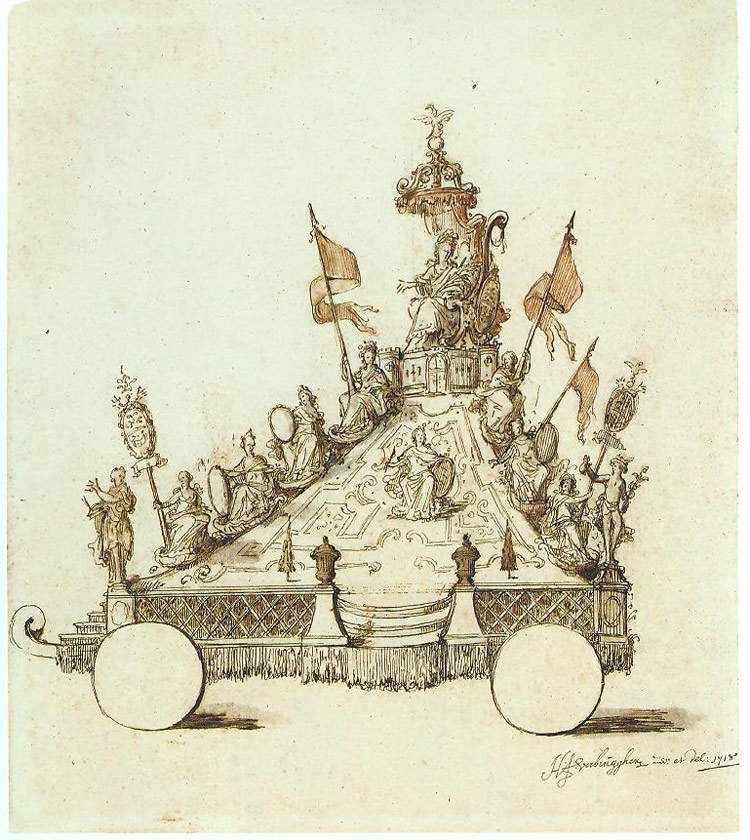

The third and final room houses the remaining three sections: the themes addressed are the Baroque feast, death, and catafalques. The festivity is analyzed and outlined in all its declinations, but it is above all the case of the triumph that became particularly congenial to Flemish sculptors and architects, who were capable of designing the most scenic and elaborate apparatuses that were to accompany the entry of princes and sovereigns into the cities of Flanders. Of particular note is the Tribune for the triumphal entry of Emperor Charles VI into Brussels, conceived by Pieter I van Baurscheit (Wormersdorf, 1669 - Antwerp, 1728) and his son Pieter II (Antwerp, 1699 - 1768), who envisioned a grand theater to be placed in Brussels’ central Place des Bailles: Referring to what the curators identify as the archetype of these grandstands, namely the theater that Rubens designed in 1635 for the entrance of Ferdinand of Austria to Antwerp, van Baurscheit father and son developed the grandstand in the form of a colonnade, placing the throne intended for the emperor under an imposing arch surmounted by an aedicule bearing symbols related to the event. The imagination of the Flemish sculptors then found vent in other types of achievements: parade floats, such as those that the aforementioned Verbrugghen designed in 1718 for theommegang (a kind of procession that in turn consisted of a religious and a secular procession) in Antwerp that year, triumphal arches, temporary theaters, and so on.

|

| Pieter I and Pieter II van Baurscheit, Tribune for the Triumphal Entry of Emperor Charles VI into Brussels (1718; pencil, pen and black ink, watercolor and gray ink on paper, 51 x 13.35 cm; Brussels, Museum van de Stad/Musée de la Ville) |

|

| Hendrik Frans Verbrugghen, Design for the carrlo The Mountain of Virgins for the Antwerp Ommegang of 1718 (1718; pencil, pen and brown ink, sanguine on paper, 42.3 x 36.4 cm; Antwerp, Plantin-Moretusmuseum, Prints Cabinet) |

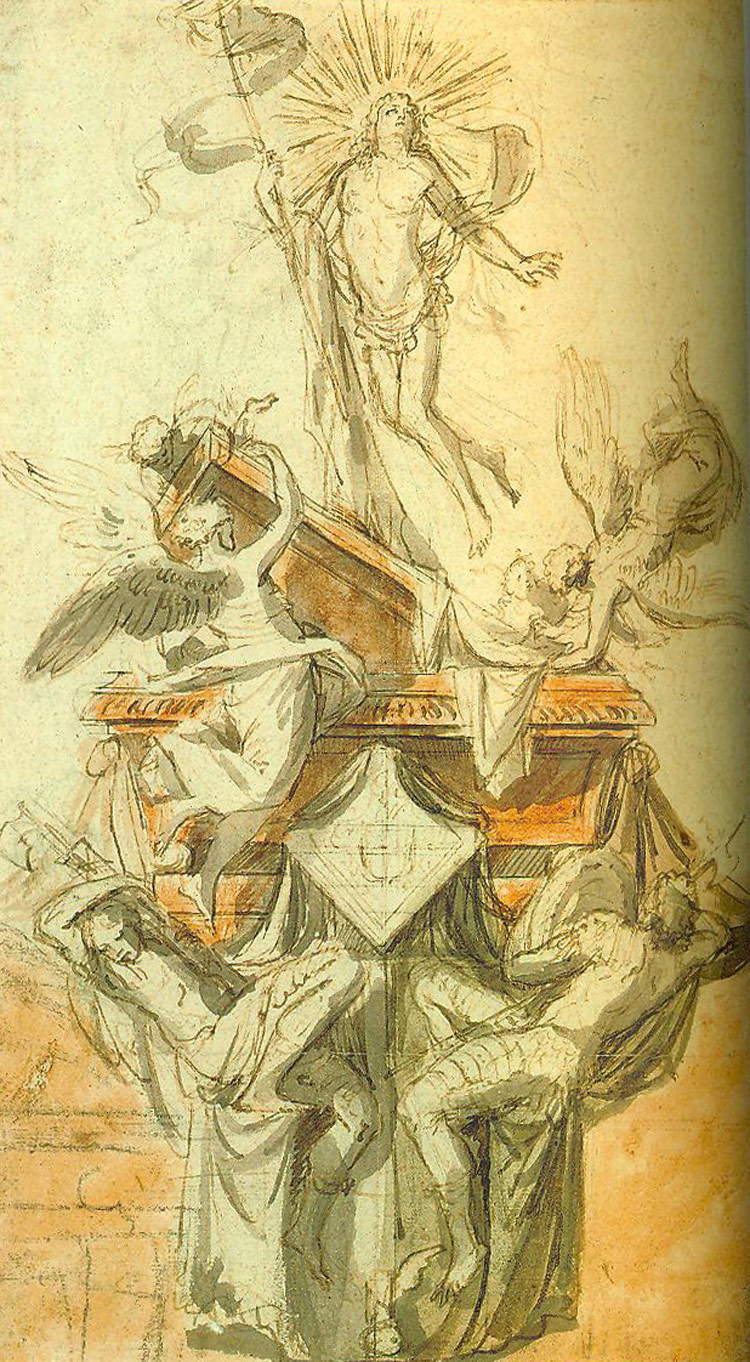

The great Baroque spectacle could not fail to involve one of the central themes of Christianity, that of death, with its load of fear at its coming and at the same time of hope as a moment of passage to an eternal life in heaven. Alongside works in which themacabre element is preponderant (a masterpiece in this regard is the Project for a Monumental Funeral Candelabra attributed to Gaspar Melchior Moens: the candles rest on a base supported by two stooped skeletons, meditating while weeping, and surmounted by two crossed sickles that crown the entire structure in the manner of flags) we find others where death, though present, is overcome by Christ: this is the case, for example, with Pieter II Verbruggen ’s (Antwerp, 1648 - 1691) Project for a Funeral Monument with the Resurrection of Christ, where the two soldiers guarding the tomb of Jesus, a symbol of death, see the latter being torn apart by the power of Christ, who emerges rising from it and ascending to heaven. The idea of the “triumph over death,” rather than that of the “triumph of death” (so Marcello Fagiolo in a catalog essay), is what animates the great designs for funerary monuments, often designed in the form of solemn catafalques, which could be erected either temporarily or permanently: in Rome they were made in honor of popes, while in the Netherlands they were intended to celebrate princes and sovereigns. And while there is no shortage of catafalques on the top of which soar symbols of death (such as the one that Wenzel Hollar designed for Prince Baltasar Carlos, son of Philip IV of Spain, crowned by a skeleton holding a sickle and a cypress tree) there are also several in which the mournful elements are nonetheless present (even as a memento mori: the faithful must know that sooner or later their time will come), but they must, indeed, succumb in the face of triumph over death: such is the case with the Project for the catafalque of Mary Elizabeth, governor general of the Netherlands, a work in which the author, still Moens (Antwerp, 1698 - 1742) placed above the entire structure an eagle ridden by a putto (the eagle is an animal associated with the ascent to heaven).

|

| Gaspar Melchior Moens (attributed to), Design for a Monumental Funeral Candelabra (1744; pen and brown watercolor, gray watercolor on paper, 32.1 x 19 cm; Antwerp, Plantin-Moretusmuseum, Prints Cabinet) |

|

| Pieter II Verbruggen, Project for a Funeral Monument with the Resurrection of Christ (black stone, pen and brown ink, brown and gray watercolor and sanguine on paper, 29.2 x 18.3 cm; Antwerp, Plantin-Moretusmuseum, Prints Cabinet) |

|

| Gaspar Melchior Moens, Project for the Catafalque of Mary Elizabeth, Governor General of the Netherlands (1741; pencil, pen and brown ink and gray and black watercolor on paper, 32.3 x 18.9 cm; Antwerp, Plantin-Moretusmuseum, Prints Cabinet) |

Inthe light of Rome is, in short, an excellent example of how an exhibition of graphic art should be organized and staged. A coherent itinerary, impeccable from the scientific point of view and good also for the popular aspect (if we want to look for the hair in the egg, perhaps we would have anticipated the whole thing with broader premises in order to provide the public with more indications on the context of reference), a trilingual catalog (with essays in Italian, French and English), rich and full-bodied, which we are sure will become an indispensable reference point for studies on the relations between Italy and Flanders in the Baroque age. Regarding the catalog, we would like to emphasize a particular aspect, apparently of little importance but actually denoting meticulous care towards the work and thoughtfulness towards the reader, namely the fact that it is equipped with an index of names, a tool too often neglected but which in a scholarly catalog is always very useful. Not to be overlooked, finally, is the fact that the exhibition is the result of a good dialogue between public institutions (Academia Belgica, Ministry of Cultural Heritage, Central Institute for Graphics), which turned out to be particularly intelligent: so kudos to those who made it possible.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.