Robert Doisneau, the photographer of the imperfection of everyday life on display in Lucca

Often life seems routine, boring, predictable to us, but sometimes it hides moments that, if caught at the right moment, make the everyday seem more unusual. Hustle and bustle, distraction, not knowing how to observe accurately cause these moments to slip past our eyes, causing us to miss the beauty of the imperfect. We believe that what fascinates us is perfection, order, and beauty, but deep down our minds and our eyes are drawn to things and situations beyond these. We look for the imperfect because we feel closer to it, more like ordinary people, since they are wonderfully imperfect, with their weaknesses and flaws.

The great gift of Robert Doisneau, a celebrated contemporary photographer, was precisely that of being able to seize the right moment to immortalize scenes of ordinary imperfection in eternity: his images, in fact, do not depict a precise and determined time, but are photographs that could have been taken in any era, in a past time that could be present, with the exception of shots in which people from the world of art and literature are portrayed. His way of photographing reflects his idea of a pêcheur d’images, fisherman of images as he called himself in the sense that a photographer must have the patience to wait for the right image to loom before his eyes, at which point he must frame the lens of his camera and take the shot. To stop forever moments in the lives of real, real people in their simple imperfection.

We understand this attitude of his well by admiring at the Lu.C.C.A. - Lucca Center of Contemporary Art in Lucca the most famous shots of the famous photographer brought together for the exhibition Robert Doisneau. A l’imparfait de l’objectif, which can be visited until November 12, 2017. Curator Maurizio Vanni has highlighted this great ability of the artist by creating an exhibition in which the visitor is taken through eighty black and white images through the streets of Paris and its suburbs, far from the mundane. Doisneau’s subjects are almost people we can meet every day in our everyday lives, such as those we find in stores, streets, alleys, schools or squares.

|

| The Robert Doisneau exhibition in Lucca |

|

| A room of the Robert Doisneau exhibition in Lucca |

One could say that the exhibition proceeds thematically in the exhibition spaces of the Lucca Center: images of characters from the world of art and literature, images of animals, and images of children, the latter favored for the spontaneity of their sometimes funny actions. Significant examples are La Sonnette (Paris, 1934), in which a small group of little boys with socks almost to their knees are quickly running away while one of them, more courageous, is ringing the bell of a doorway-a mischief that many of those reading this will have been up to as children. Intrigued by the scene is a little girl in a checked dress who has stopped right in front of that doorway-who knows what she must be thinking.

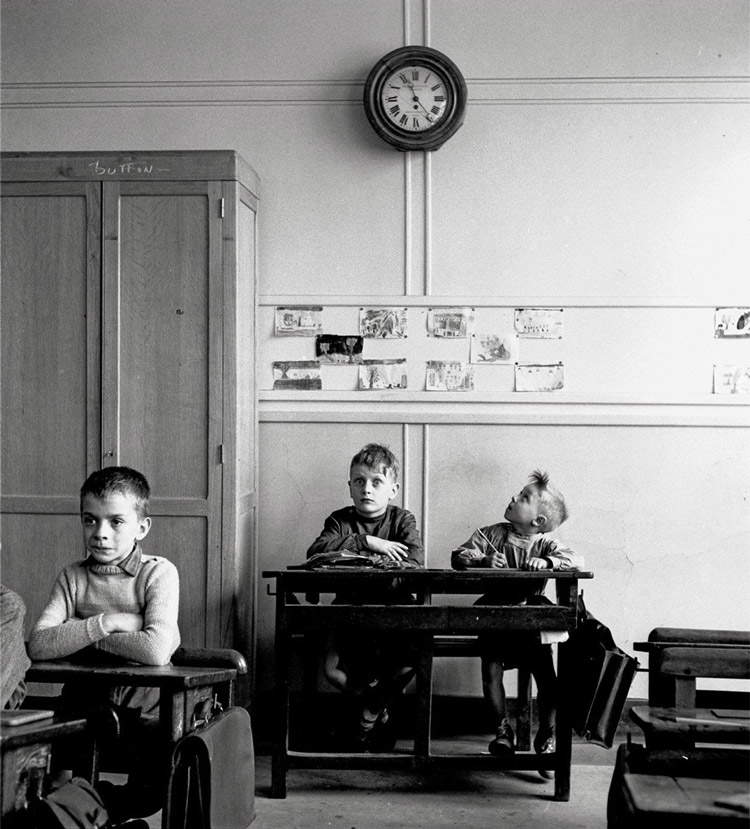

Or Le cadran scolaire (Paris, 1956): the title of the shot literally refers to the face of a clock found in a school classroom. The object of great attention by a child with a funny little unruly forelock is in fact the wall clock hanging right behind him, but too high up to look at without being noticed. The child in question is with his nose turned up and his mouth slightly open in the typical expression of someone who is straining to be able to see something, heedless perhaps of the explanation of the teacher who is presumably standing in front of the three schoolchildren; the other two children appear attentive and strutting with their arms folded, although the desk-mate of the child who is looking at the clock seems to have his gaze fixed in the void, as of someone who wants to give the impression that he is listening, but in fact is not, while the child more in the foreground is distracted by someone or something to his right, since only his gaze is directed in that direction. Another very common scene in a classroom is the one depicted in L’information scolaire (Paris, 1956): here while a child is thinking concentrating, with his eyes turned upward, on solving the task he is doing on his blackboard, his deskmate takes the opportunity to copy almost indifferently what the other has already written.

Outside the school setting, but still starring children, however of a younger age than those portrayed in the previous images, is the photograph titled Les tabliers de Rivoli (Paris, 1978): a long line of children is crossing the street, single file, holding each other by the apron of their companion in front; they have momentarily blocked traffic, creating in turn long queues of cars.

|

| Robert Doisneau, La sonnette (Paris, 1934) |

|

| Robert Doisneau, Le cadran scolaire (Paris, 1956) |

|

| Robert Doisneau, L’information scolaire (Paris, 1956) |

|

| Robert Doisneau, Les tabliers de Rivoli (Paris, 1978) |

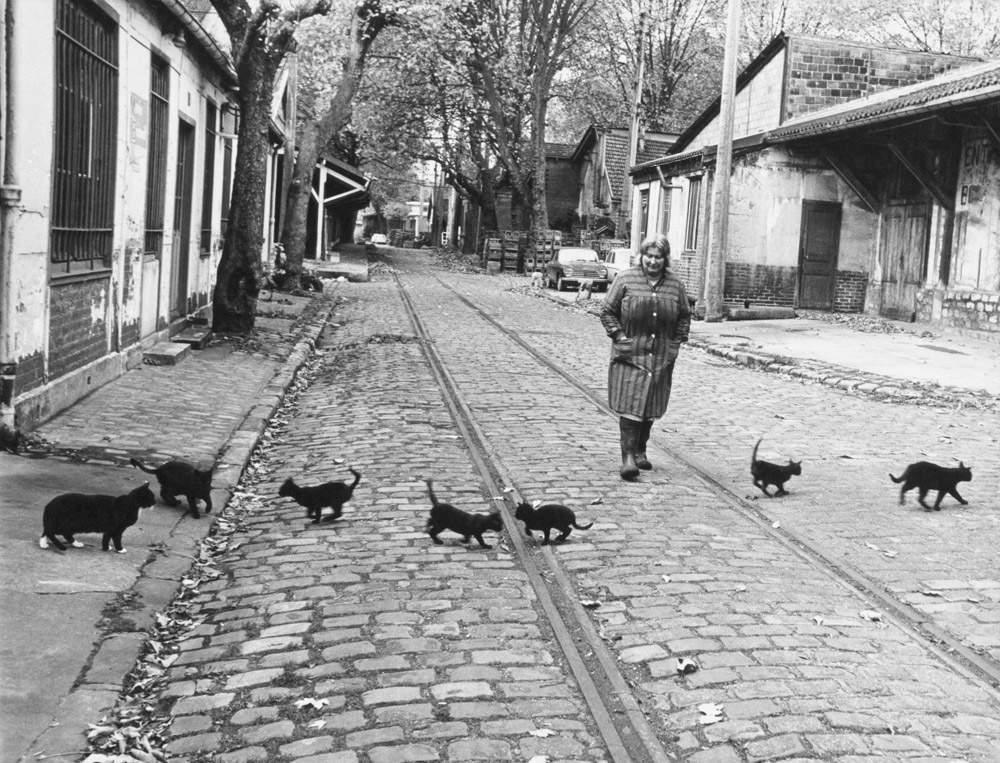

If for shots of children Doisneau had a certain soft spot, he nevertheless had a soft spot for animals: we find them depicted in Les chiens de la Chapelle (Paris, 1953), where two friendly dogs stand motionless on two legs, arousing the curiosity of two passers-by, or in Fox terrier au pont des Arts (Paris, 1953), in which the dog in question is looking, almost posing, toward the photographer’s lens, remaining behind its owner who is instead admiring from the opposite side an artist at work on his canvas. Or again in Les chats de Bercy (Paris, 1974): the protagonists this time are some black cats in the middle of a narrow street in the Parisian neighborhood of Bercy. Particularly singular is Le singe de Monsieur Bayez (Paris, 1970), otherwise known as Le singe et le marqueteur, or the monkey and the inlayer: in the inlayer’s workshop, the monkey watches attentively the work being done by his master.

|

| Robert Doisneau, Les chiens de la Chapelle (Paris, 1953). |

|

| Robert Doisneau, Fox terrier au Pont des Arts (Paris, 1953) |

|

| Robert Doisneau, Les chats de Bercy (Paris, 1974) |

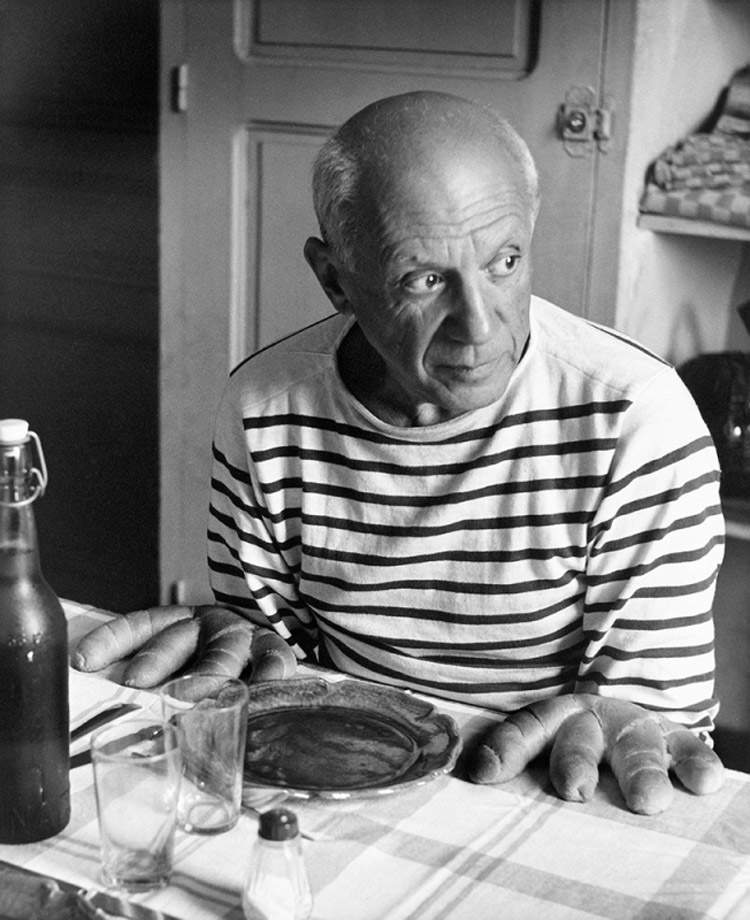

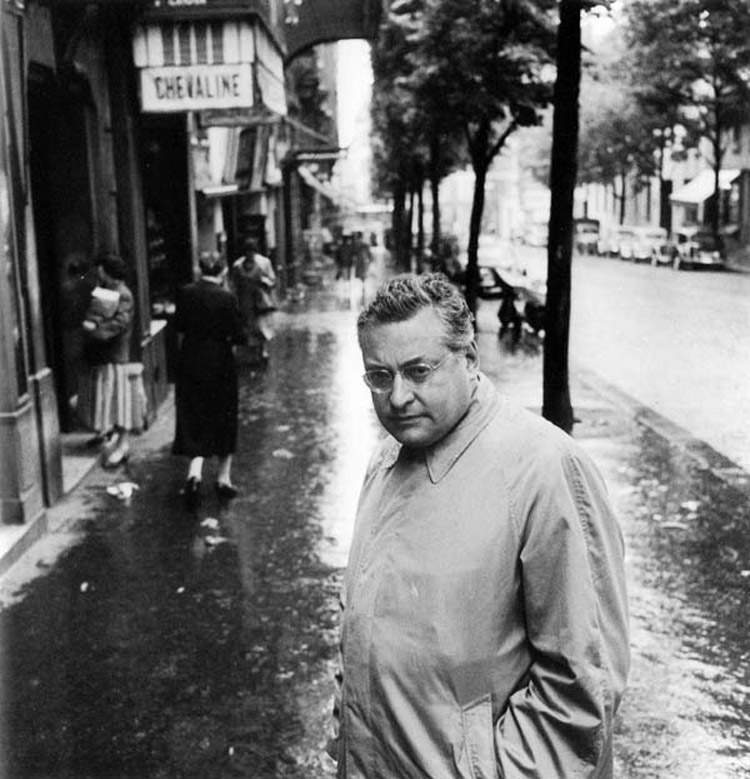

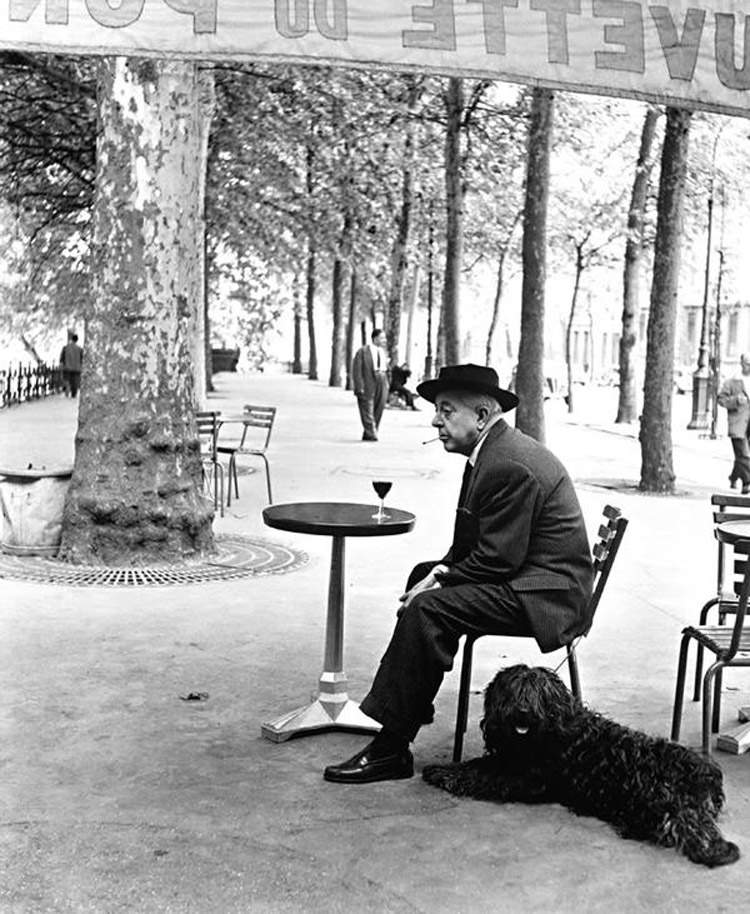

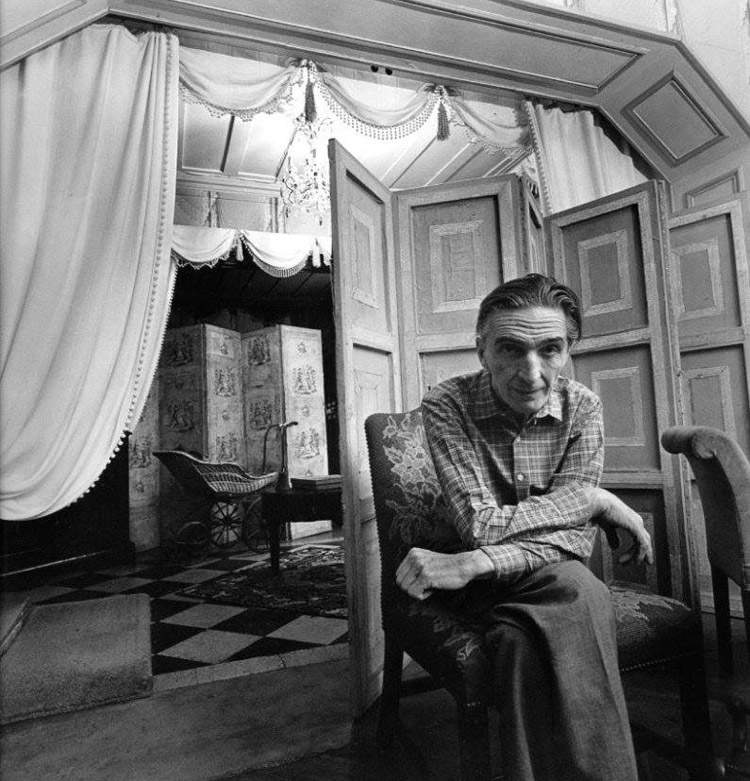

Doisneau also immortalized in his photographs many celebrities from the world of art and literature, such as Picasso in Les pains de Picasso (Vallauris, 1952), in which the great artist, wearing a striped T-shirt, appears to have disproportionate hands on the table, but they are actually sandwiches placed in the shape of hands; the writer Raymond Queneau as he strolls down the Rue de Reuilly on May 31, 1956; the writer and philosopher Simone de Beauvoir at the Parisian café Les Deux Magots in the Saint-Germain-des-Près neighborhood (Paris, 1944); the poet Jacques Prévert in Jacques Prévert au guéridon (Paris, 1955), in which the poet is sitting at a kiosk table with a glass of wine in the company of a large dog that crouches down and is watching us. And again the painter and sculptor Jean Fautrier (Chatenay Malabry, 1960), the painter Fernand Léger among his works (Gif sur Yvette, 1954), and the painter and sculptor Jean Dubuffet in his studio (Paris, 1954), as well as himself in the self-portrait showing him with a camera in his hands (Villejuif, 1949).

|

| Robert Doisneau, Les pains de Picasso (Paris, 1952) |

|

| Robert Doisneau, Raymond Queneau en rue de Reuilly le 31 mai 1956 (Paris, 1956) |

|

| Robert Doisneau, Jacques Prévert au guéridon (Paris, 1955) |

|

| Robert Doisneau, Robert Doisneau, Fernand Léger dans ses oeuvres (Gif-sur-Yvette, 1954) |

|

| Robert Doisneau, Jean Fautrier (Chatenay Malabry, 1960) |

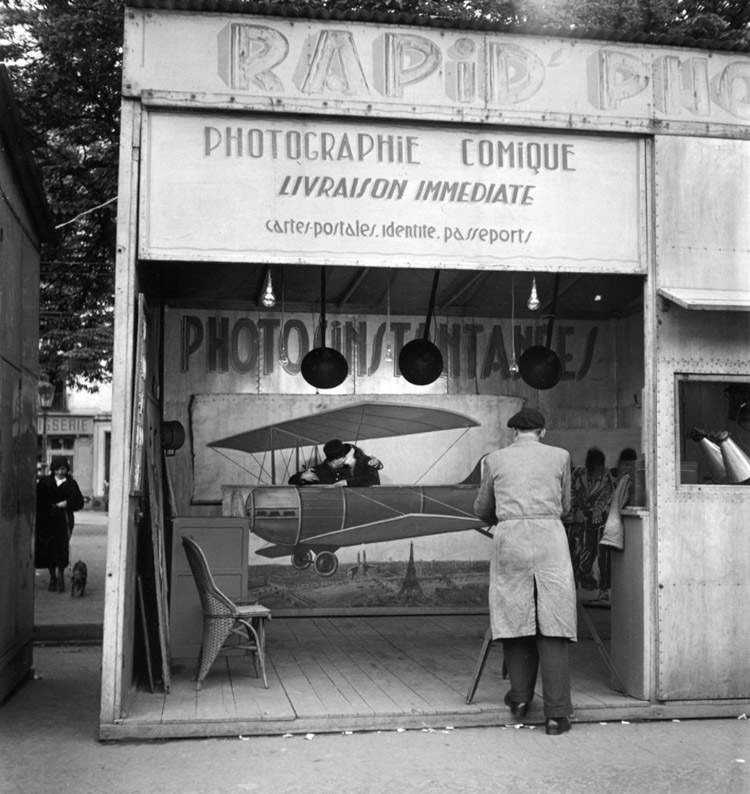

In the exhibition of the great photographer’s most famous shots, our attention is immediately drawn to the unfailing Le Baiser de l’Hôtel de Ville (Paris, 1950), that kiss that will forever remain etched in the history of photography, where the protagonist is an ordinary couple in love exchanging a romantic and passionate kiss among passers-by. It seems that nothing exists around them, that the world is flowing, but they are there and now and that is all that matters. But this is not the only kiss in the exhibition: we also find the one depicted in Photographie aérienne (Paris, 1950). Here we see a photographic set for instant photographs, where the setting is an airplane, in such a way as to make it look like the two lovers are having a nice kiss at high altitude.

Robert Doisneau is the photographer of stolen kisses, of the everyday adventures of young boys, of the funny expressions of four-legged companions, but also of ordinary street chatter or gossip between rich comedians, of ridiculous store scenes and prying glances. He is the photographer of the atypical in the everyday, of the imperfection of normality, and perhaps that is precisely why he fascinates us so much, because we might dream of finding ourselves among the many characters who animate his images.

|

| Robert Doisneau, Le Baiser de l’Hôtel de Ville (Paris, 1950) |

|

| Robert Doisneau, Photographie aérienne (Paris, 1950) |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.