by Federico Giannini (Instagram: @federicogiannini1), published on 16/01/2017

Categories: Exhibition reviews

/ Disclaimer

Review of the exhibition 'The Time of Signorini and De Nittis. The Nineteenth Century Open to the World in the Borgiotti and Piceni Collections' in Viareggio, Matteucci Center, from July 2, 2016 to February 26, 2017

After last year’s excellent exhibition dedicated to Silvestro Lega, expectations for the 2016-2017 appointment of the Matteucci Center for Modern Art Foundation in Viareggio could only be decidedly high. Not least because, for this year’s exhibition, the Center chose a decidedly high-sounding title: The Time of Signorini and De Nittis. The Nineteenth Century Open to the World in the Borgiotti and Piceni Collections. The exhibition venue has remained true to its vocation for theItalian Ottocento: however, gathering works by heavy names (in addition to Signorini and De Nittis, on display are Zandomeneghi, Boldini, Fattori, Lega and others) and setting the (brief) itinerary by trying to provide the public with a reconstruction of the collections of Mario Borgiotti and Enrico Piceni are not sufficient operations to create an interesting and, above all, memorable exhibition. Moreover, the fact that the exhibition comes six years after a more comprehensive exhibition that the Matteucci Center had already dedicated to the figure of Mario Borgiotti should have warned of the possibility of being faced, at the very least, with feelings of déja vu: many of the works on display, in fact, are those that had already been seen on the occasion of the Genio dei macchiaioli exhibition. Which, of course, is certainly not a bad thing, not least because it was hoped that the interesting Piceni-Borgiotti confrontation could become a pretext for a dense, original review, capable of making the public discover these two important as well as little-known figures of the early twentieth-century art scene. The outcome, however, did not live up to expectations.

|

| The exhibition poster in front of the entrance to the Matteucci Center |

|

| A passage from the exhibition |

In fact, in the intentions of the curators, Claudia Fulgheri and Camilla Testi, the exhibition was supposed to provide a “tale in pictures” of the “tussle” between the two refined collectors, Mario Borgiotti and Enrico Piceni precisely, who contributed in a decisive way to the fame of the Macchiaioli (Borgiotti) and the Italians of Paris (Piceni). The images are there, but the narrative is completely lacking. Of course: setting up an exhibition on collecting is always a courageous and difficult operation, and credit must be given to the curators for that. However, good intentions are not always rewarded by results. The exhibition presents itself to the visitor as a brief sequence of works from the Piceni and Borgiotti collections (the visual directives are underscored, in the layouts, by two colors: gold for Piceni and green for Borgiotti), lacking, however, the narrative that should have accompanied him or her along the halls of the Matteucci Center. The consequence is that the visitor leaves without being given answers to some fundamental questions: how did Piceni enhance the art of Zandomeneghi, De Nittis, Boldini? And how did Borgiotti succeed in the same operation for the Macchiaioli? How were the collections of the two critics formed? How were they embedded in the artistic environment of the time? Why is so much weight given to the works of Zandomeneghi in Piceni’s collection? Which were Piceni and Borgiotti’s favorite artists, with whom did they have the most consistent relationships?

It is necessary to point out that not only are answers to these questions lacking, but no elements are even provided to try to get at the questions that a visitor, in an exhibition on collecting (and where, moreover, one of the two collections is the one that belonged to the critic who perhaps more than any other contributed to the success of Zandomeneghi and De Nittis), legitimately asks. The only useful foothold is a panel that summarizes for us, rather quickly and, if you will, superficially, the differences between the aesthetic conceptions of the two collectors: devoted to “technical-formal analysis” Borgiotti’s, founded on the assumption that beauty is pleasure Piceni’s. Then there are two large introductory panels through which the figures of Enrico Piceni and Mario Borgiotti are presented to the public, with certain emphasis (perfectly unnecessary where the text spells out “rich and significant, in the exhibition’s itinerary, the selection of paintings and pastels by Federico Zandomeneghi”: the visitor sees very well for himself that the exhibition abounds with works by Zandomeneghi... instead, it would have been more interesting to explain, precisely, why there is a rich and significant selection of works by the Venetian artist in the exhibition) but also with references that are difficult for a general audience to understand. This happens, for example, when it is said that Borgiotti “is assimilated to a Vollard, a Pospisil, or a Barbaroux, rather than to the militant intellectual and critic”: excluding Vollard, known to some aficionados above all for having been Picasso’s gallerist, who painted his portrait, the names of Francesco Pospisil and Vittorio Emanuele Barbaroux, two merchants active in the early twentieth century, are known almost exclusively by art experts of the time. Also hallucinating is the decision to include the chronologies of the lives of Piceni and Borgiotti after the tour is over, in the last room, on six large panels filled with notions that are of little use to the exhibition’s narrative. And then, let’s face it: at the end of an exhibition, after spending an hour or more among the works (about forty or so), and taking it for granted by now that the “narrative” bandied about at the beginning of the itinerary is in fact not there... who feels like spending at least another ten minutes to read a chronology that, if anything, made more sense at the opening?

|

| Wall with painting by Zandomeneghi on the left and painting by Oscar Ghiglia on the right |

|

| The panels with Mario Borgiotti’s chronology. |

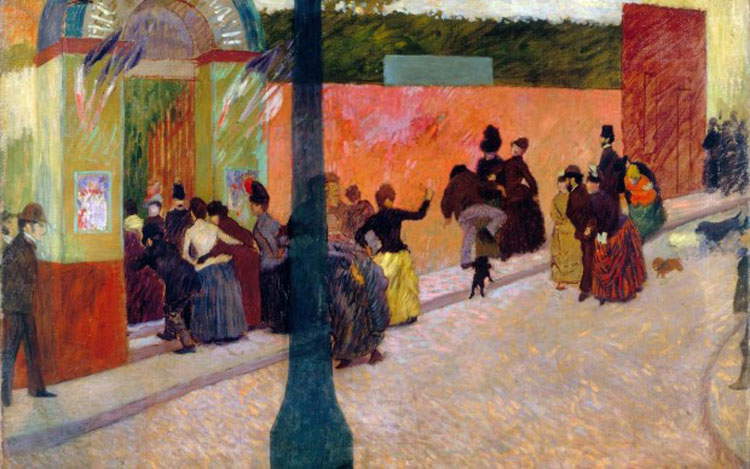

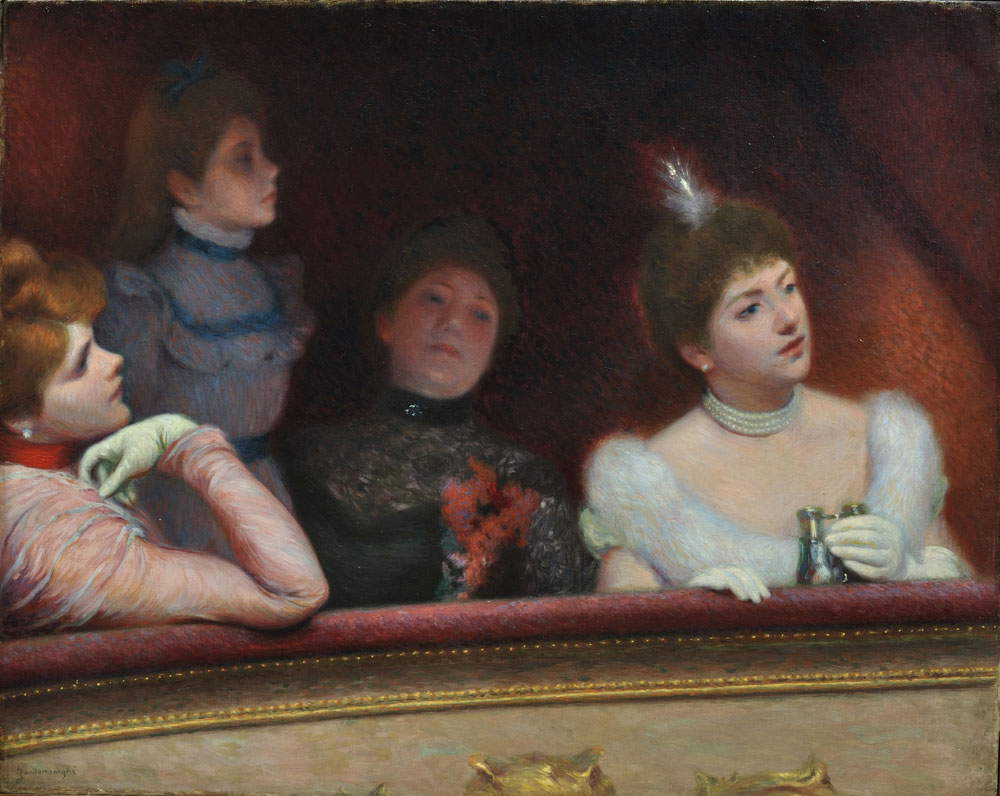

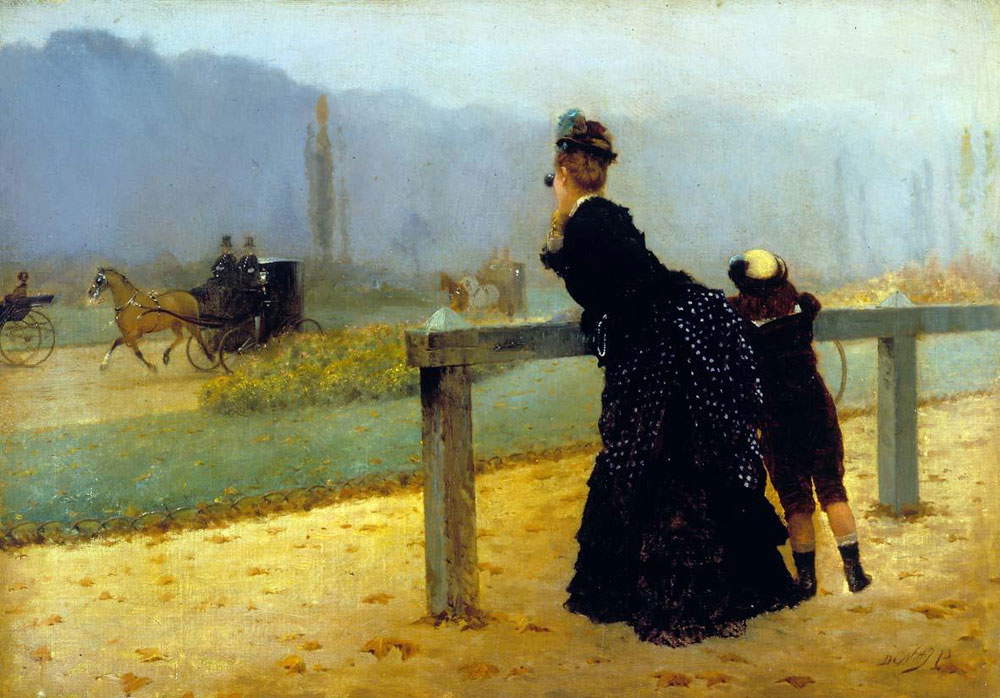

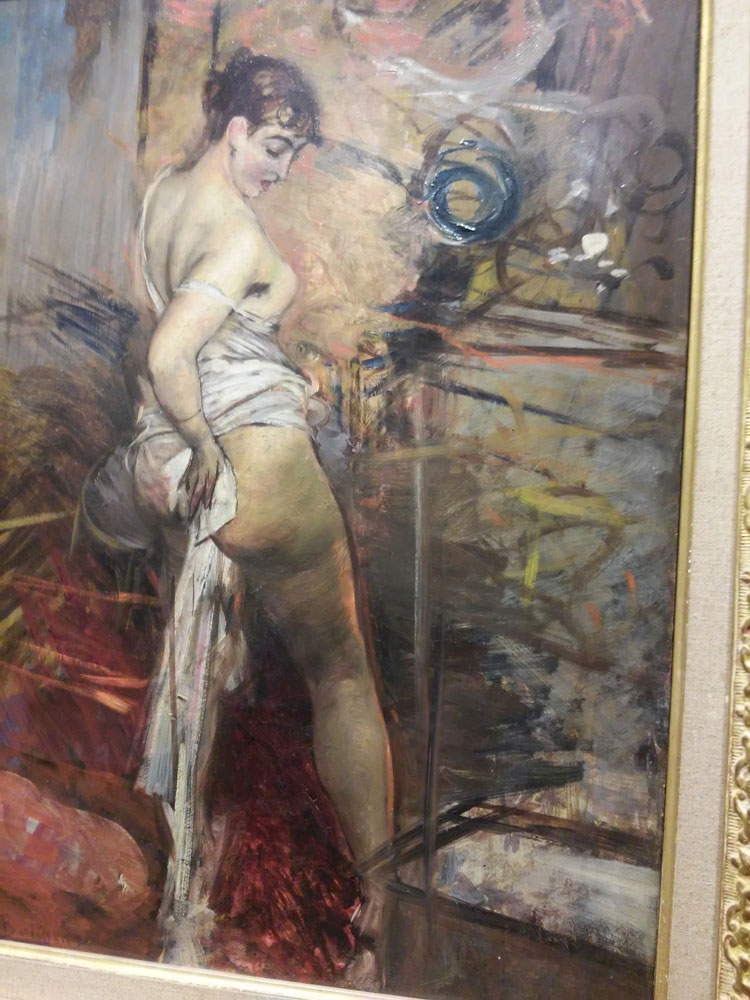

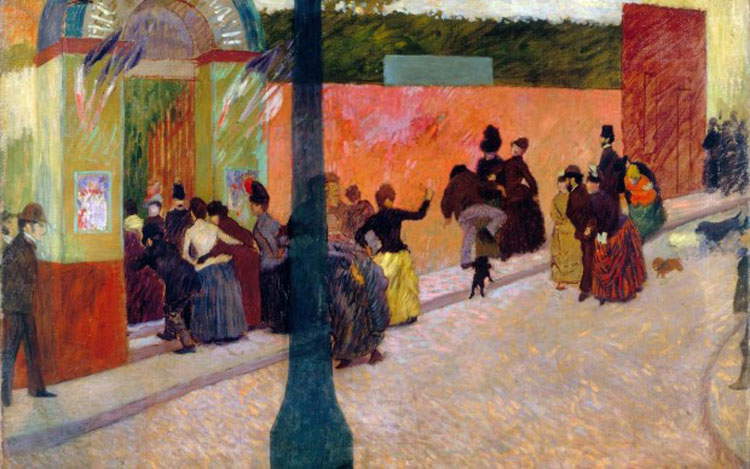

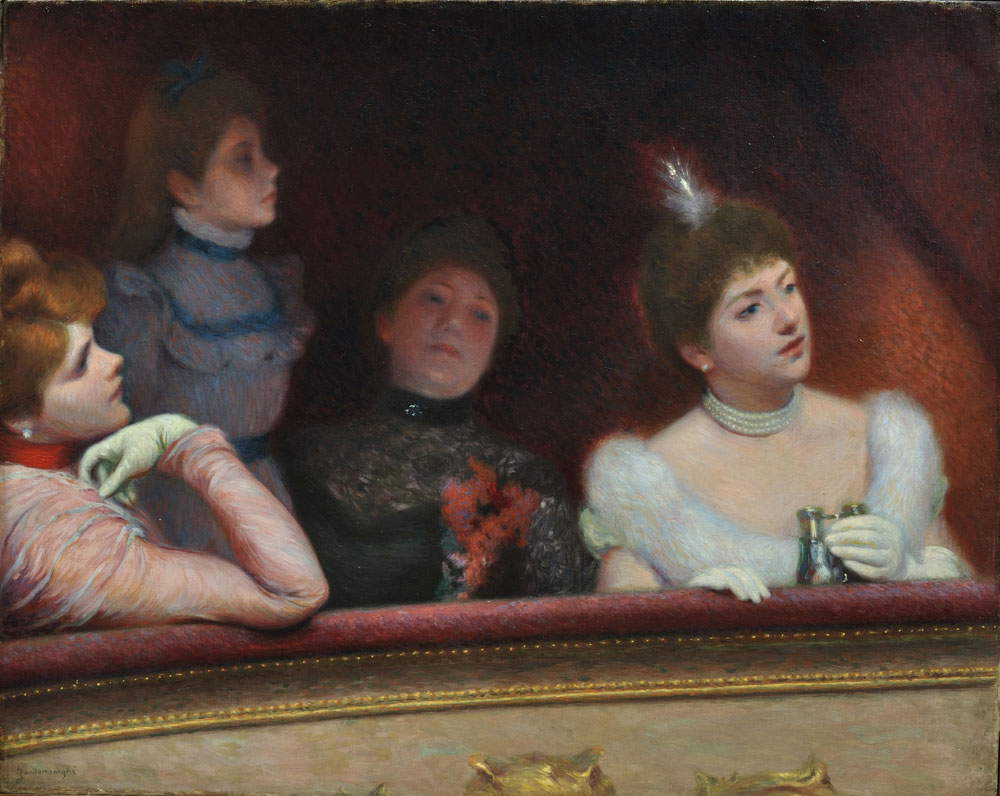

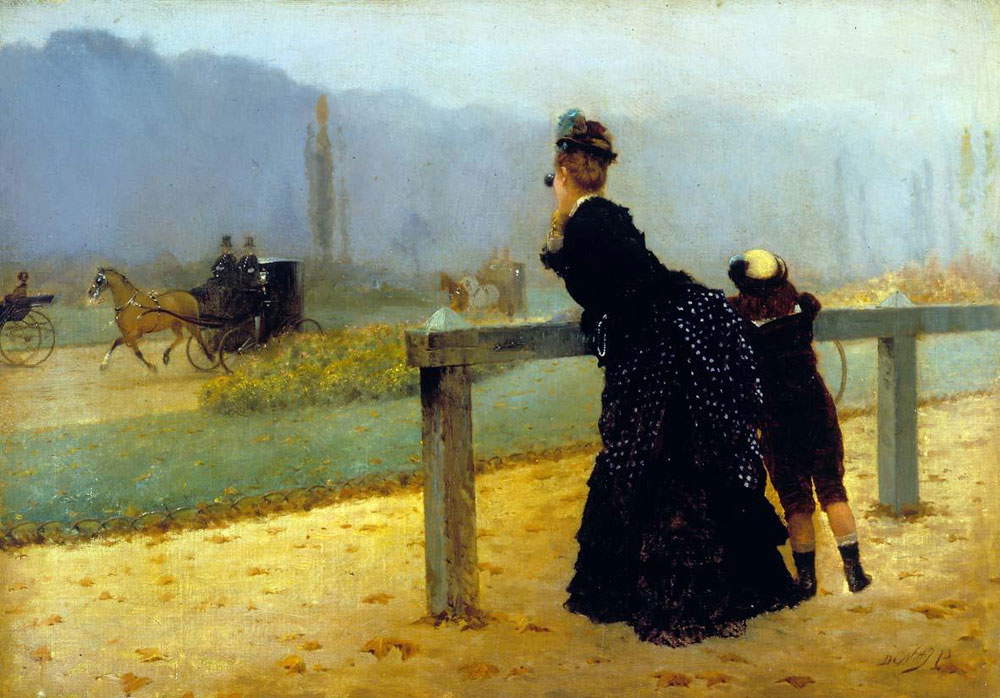

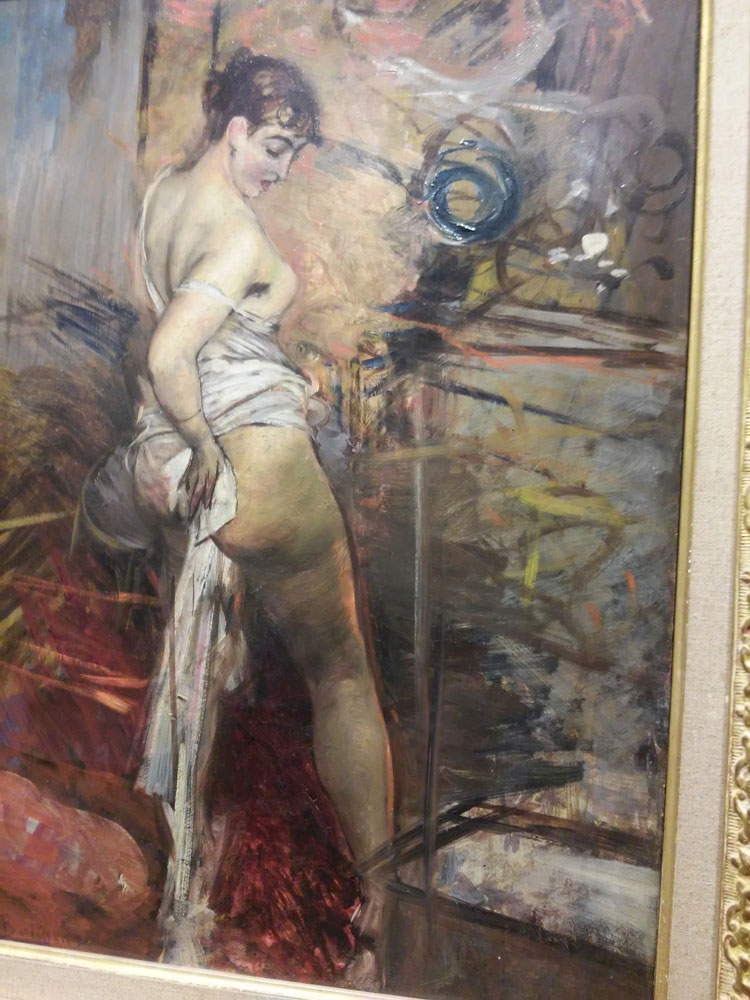

All that remains, then, is to make up for it with the very high quality of the works on display, which are sure to fully satisfy fans of late 19th-century art. The roundup of works by Federico Zandomeneghi is worth, practically alone, the entire exhibition. These are works from the Piceni Foundation’s collection that are not normally on view, so the Viareggio exhibition is a welcome opportunity to view them. We have both the worldly Zandomeneghi(Au Théâtre, from 1895, presents us with four women leaning out from the box of a theater, while Moulin de la Galette from 1878 is, as the introductory panel says in one of the few splashes truly for public use, a “painting of the greatest impact , ingenious and daring in composition,” which “anticipates in its daring solutions some aspects of Toulouse-Lautrec”), as well as the more intimate one, the refined poet of feminine sweetness, as we notice when observing Le repos, a portrait of a little girl lying on a meadow playing with a blade of grass, bringing it to her mouth. Also noteworthy is the selection of works by Giuseppe De Nittis, including Nei campi intorno a Londra (In the fields around London), in which a group of young people stretch out in the most carefree manner over a flowery meadow, and the exceptional Al bois de Boulogne (In the woods of Boulogne), from 1873, which depicts a moment of everyday life in Paris at the time: a richly dressed mother, in the company of her young son, watches a carriage pass through the alleys of the Bois de Boulogne. Striking at the end of the route is a Toilette by Giovanni Boldini, starring a procubescent lady whom the artist catches, with the eye of a seasoned voyeur, as she passes a towel between her private parts.

|

| Federico Zandomeneghi, Moulin de la Galette (1878; oil on canvas, 80 x 120 cm; Piceni Foundation Collection) |

|

| Federico Zandomeneghi, Au Théâtre (ca. 1895; oil on canvas, 71 x 88 cm; Piceni Foundation Collection) |

|

| Giuseppe De Nittis, Al Bois de Boulogne (1873; oil on canvas, 23 x 34 cm; Piceni Foundation Collection) |

|

| Giovanni Boldini, La Toilette (1885; oil on panel, 55 x 45 cm; Piceni Foundation Collection) |

The selection of paintings from the Borgiotti collection (which is still owned by the critic’s descendants: so, again, a rather rare opportunity to see the works) opens with a few canvases by Giovanni Fattori, continues with some intense portraits and interior scenes (such as Silvestro Lega’s Bigherinaia, or a weaver of “bigherini,” the term used in Tuscany to indicate lace for women’s clothes, or such as Adriano Cecioni’s Solletico, which depicts a moment of play between two little girls), continues with a series of splendid and evocative landscapes by Giuseppe Abbati painted on the beaches of Castiglioncello, unravels among works by Cabianca, Sernesi and Signorini (the latter’s Women at Riomaggiore is particularly interesting) and ends in front of Antonio Mancini’s very special Recreation, a little girl with an indefinite expression clutching a doll and sitting next to some playthings.

|

| Giuseppe Abbati, The House of Diego Martelli in Castiglioncello (1862; oil on canvas, 21 x 50 cm; Borgiotti Collection) |

|

| Adriano Cecioni, The Tickling (1862; oil on canvas, 37.5 x 44.5 cm; Borgiotti Collection) |

|

| Telemaco Signorini, Women at Riomaggiore (1893; oil on canvas, 64.5 x 44.5 cm; Borgiotti Collection) |

|

| Antonio Mancini, Recreation (c. 1876; oil on canvas, 160 x 103 cm; Borgiotti Collection) |

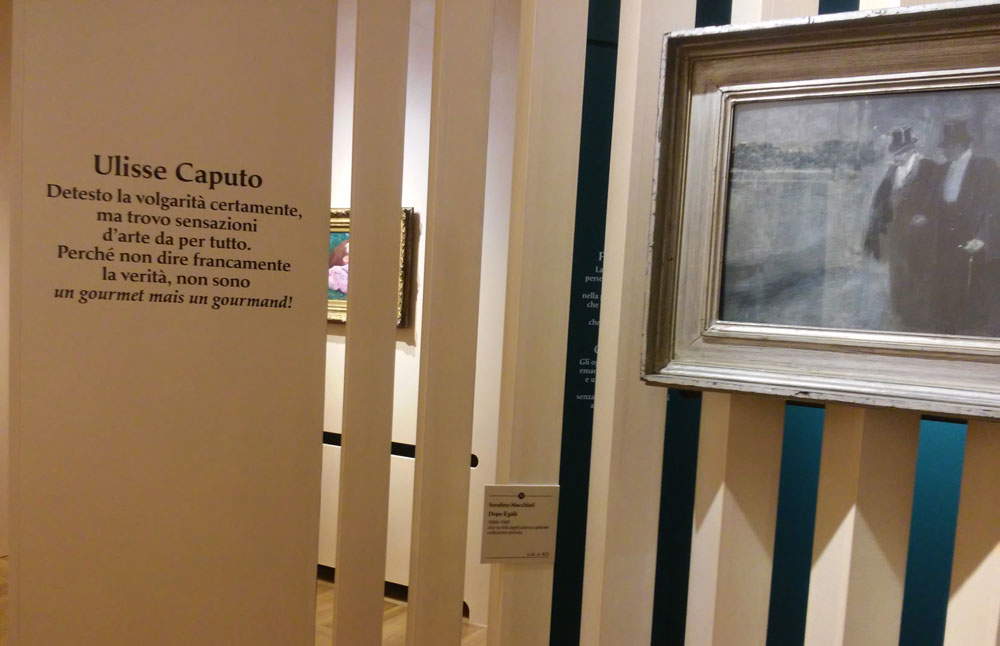

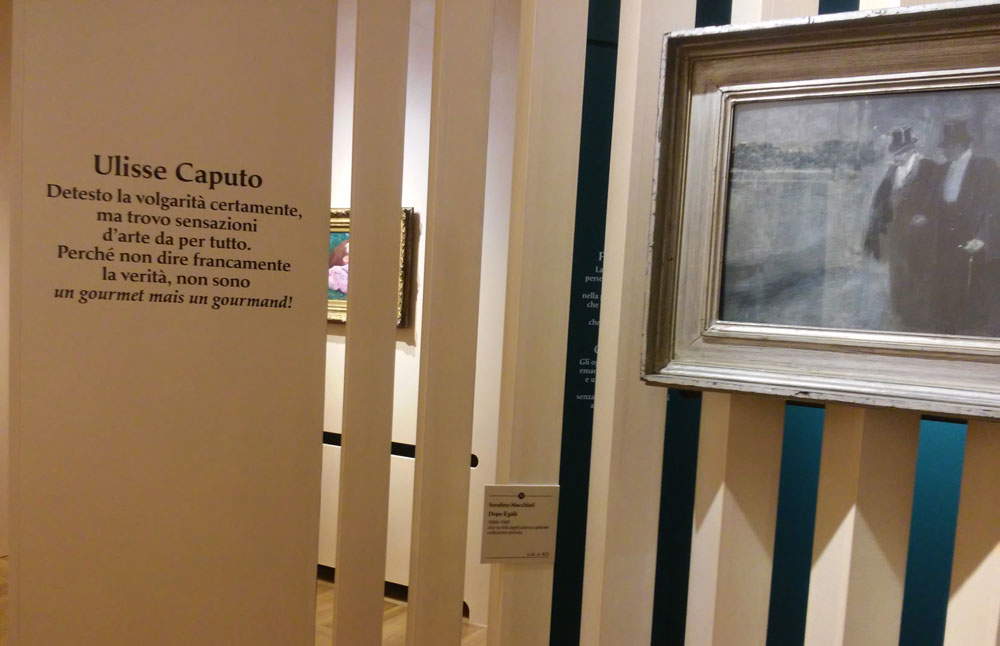

The visitor who pauses to analyze trends and differences in the two collections will be able to come to the conclusion that Borgiotti preferred alyrical, meditative, silent art (sunsets on beaches devoid of human presences, quiet vineyards colored in autumn, solitary walks in the countryside, village comari confabulating under their breath, children caught in their games) and Piceni was more attuned to busy city life, from London to Paris among streets, squares, parks, theaters, and busy clubs. To arrive at such conclusions, the panels can be helpful, which, with pills taken from Borgiotti’s and Piceni’s texts, introduce the painters in the exhibition to the public: De Nittis is thus the painter “who taught the English to see their fogs and the French to see their women,” Boldini “left with his work a vast and varied testimony embracing all aspects of the human fable: idyll and tragedy, fever and gossip, the breath of the fields and marinas and the spoiled warmth of drawing rooms,” and again Abbati knows that “the exterior is the mysterious state of an inner world that needs to be revealed,” and Cecioni is a painter gifted with “critical acuity, expressive vivacity and penetrative spirit.” It is just a pity that sometimes these captions are placed in an unintuitive manner: it is not clear why, for example, the panel on Ulisse Caputo was placed next to a work by Serafino Macchiati and, vice versa, Macchiati’s caption accompanies a painting by Caputo (the portrait of his wife: one of the most intense works in the entire exhibition).

|

| The caption on Ulysses Caputo next to Serafino Macchiati’s After the Gala. |

|

| Last passage of the exhibition with, in the background, the portrait of Maria Sommaruga, wife of Ulisse Caputo author of the painting |

Finally, a note on the catalog (a good one) is due, which includes two essays, one on Piceni and one on Borgiotti by Camilla Testi and Claudia Fulgheri respectively, and the contribution by Flavie Durand-Ruel, a descendant of the very famous merchant of the Impressionists, and the lengthy introduction by the indefatigable Giuliano Matteucci, director of the Foundation, also deserve a mention. Rich and timely, moreover, are the fact sheets on the paintings. A catalog that, in short, makes up for the (too many) shortcomings of an exhibition that, while not shaping up to be an empty joke (there was great potential, unfortunately little exploited), and while remaining an all in all elegant exhibition animated by excellent intentions, in the roster of the Matteucci Center’s exhibitions passes somewhat underwhelmingly, rather disappointing because of its lack of ability to express itself fully, its obvious popularizing shortcomings, its decidedly high admission cost when judged in relation to the contents of the exhibition, and its failure to achieve the goal of presenting to the public in a comprehensive way the figures of those who were supposed to be the two main protagonists of the exhibition’s narrative. It is to be hoped that the next exhibition will be able to reproduce for us the level of last year’s exhibition: the Matteucci Center, a serious and well-run institution, is fully capable of doing so.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools.

We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can

find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.