by Federico Giannini (Instagram: @federicogiannini1), published on 20/12/2016

Categories: Exhibition reviews

/ Disclaimer

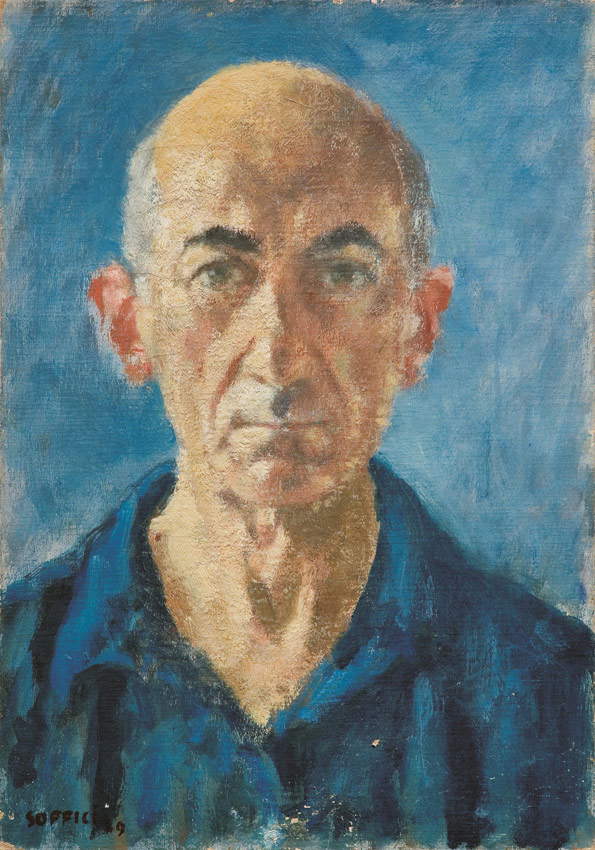

Review of the exhibition 'Discoveries and Massacres. Ardengo Soffici and the Avant-Garde in Florence', at the Uffizi until January 8, 2017.

Cézanne, Renoir, Pissarro, Toulouse-Lautrec, Rousseau, Picasso, Braque. And then of course he, the great protagonist, Ardengo Soffici (Rignano sull’Arno, 1879 - Vittoria Apuana, 1964). The names and prerequisites to turn the first-ever monograph on Soffici into a shanty-style “From Renoir to Picasso: the years of Ardengo Soffici” were all there. But the Uffizi Gallery, as those who have been frequenting it for years know, is still, despite everything, a solid bastion of scientific and popular seriousness, which is why the exhibition, for which curators Vincenzo Farinella and Nadia Marchioni chose the significant title Scoperte e massacri. Ardengo Soffici e le avanguardie a Firenze alluding to one of the main books of Soffici’s production(Scoperte e massacri precisely, a collection of articles published in 1919), resulted instead in a small masterpiece worthy of all praise.

One thing must be made clear right away, however: the real tests of the Schmidt management are yet to come because, for this year’s exhibitions, we are still talking about operations conceived when the current director was probably still compiling the curriculum to send to the Ministry for the 2015 competition. The director, however, had the insight not to alter too much the old concept of “A Year in Art,” putting the various exhibitions of Uffizi and related museums (Gallery of Modern Art, Palatine Gallery) in a common context. The choice, for now, is rewarding: sure, the hand of the old management is well present and you can sense it even just wandering around the rooms of Discoveries and Massacres. The imprint of Antonio Natali, among the creators of the exhibition, is quite evident (right from the lexical choices of the descriptions in the panels): so we will have to wait and see what the “100% Schmidt” exhibitions will be like, also in light of the fact that the former director has retired, but hopefully his legacy will not be too altered. In the meantime, we can enjoy this splendid exhibition on Ardengo Soffici, which features that linear, extraordinarily effective dissemination cut typical of Vincenzo Farinella’s exhibitions (Virgilio-style in Mantua in 2011 or Dosso Dossi in Trento in 2014). An exhibition on Ardengo Soffici that is as much snubbed and underrated as it is complete, if we want even entertaining, and certainly surprising, full of unexpected pearls and scientifically inapposite.

|

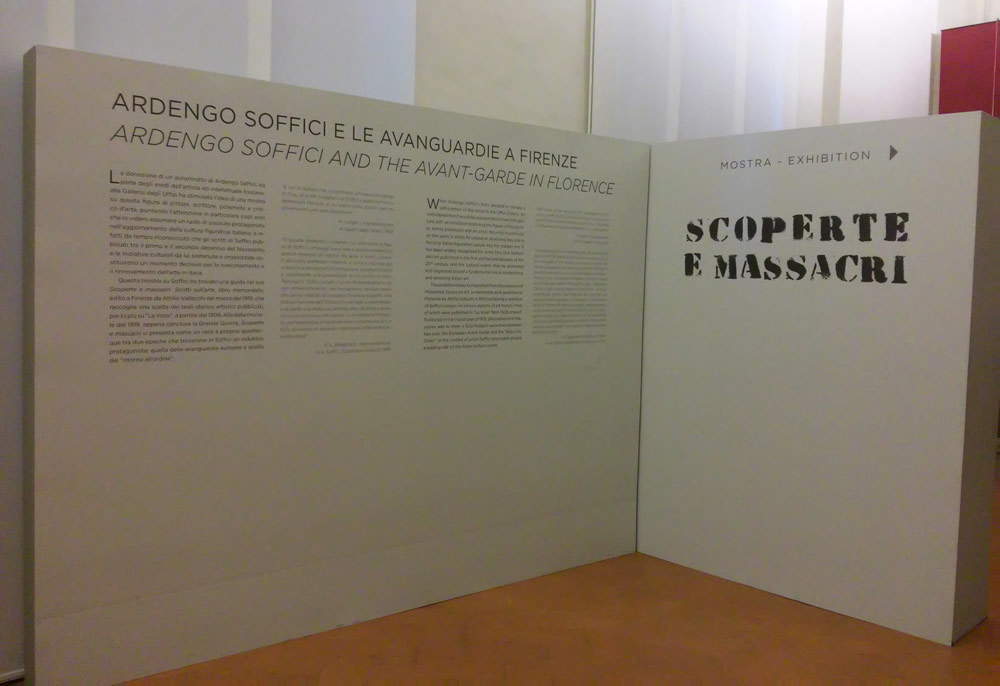

| The introductory panels of the exhibition |

|

| One of the rooms of the exhibition |

|

| Leonardo Bistolfi, The Brides of Death (1895; plaster, 275 x 100 cm; Casale Monferrato, Museo Civico, Gipsoteca) |

The Ardengo Soffici that the exhibition examines is not the staunch, fascist supporter of the regime who, from the 1920s onward, sharply narrowed his own limits, hermetically closed his eye on the most developed art, and whose remaining forty years of life remain neglected by most today. He is the young Ardengo Soffici, the bohemian who in early twentieth-century Paris illustrates fashionable magazines and is fascinated by the Impressionists, the Nabis, and Cézanne; he is the critic who organizes the first Impressionist exhibition in Italy; he is the attentive observer who makes the Italians discover Picasso and the Cubists, he is the polemicist capable of unconditionally praising Rousseau and violently crushing Franz von Stuck, Telemaco Signorini, Giulio Aristide Sartorio and a host of other artists mercilessly demolished with criticism often bordering on insult. Discoveries and massacres, indeed. The avant-garde discovered and brought to Italy, and the artists despised, bitterly massacred, almost denigrated, often because according to Ardengo Soffici they were false and constructed, incapable of feeling.

The exhibition opens with a teenage Ardengo Soffici who, not even eighteen years old, visits in 1896 theEsposizione dell’Arte e dei Fiori in Florence, a major international art (and horticultural: yes, it sometimes happened at the time) exhibition, where the young Soffici has the opportunity, for the first time, to come into contact with the latest Italian and French art. He was struck by a portrait by Léon Bonnat whose subject was the writer Ernest Renan (pudgy, ugly, with neglected hands resting crudely on his thighs, but caught with incredible naturalness); he was fascinated by the sculptures of Leonardo Bistolfi, present in the exhibition with the Brides of Death and an author who, a not uncommon case in Soffici’s career, would first be “discovered” and then “slaughtered” (just three years after writing an appreciative article, Soffici would brand him as a “false, faint-hearted, and bolshy” artist), but above all he is thunderstruck by the sight of the works of Giovanni Segantini (on display with an evocative work such as The Angel of Life), whose painting reminds him of “the poetic, georgic style and manner of the Frenchman Millet,” who is his favorite painter.

|

| Léon Bonnat, Portrait of Ernest Renan (1892; oil on canvas, 110 x 95 cm; Tréguier, Maison Natale d’Ernest Renan) |

|

| Giovanni Segantini, The Angel of Life (1894-1895; oil and gouache on paper, 59.5 x 48 cm; Budapest, Szépmuvészeti Múzeum) |

So much attraction to France could only lead to a stay in Paris, which Ardengo Soffici made between 1900 and 1907. In Paris, Soffici discovered Paul Cézanne, Maurice Denis, and Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, who became the first points of reference for his art: the third room of the exhibition features two works such as Puvis de Chavannes’ Les jeunes filles et la mort, whom Soffici considers “a powerful genius who has filled the nauseating void of our time and forms with Segantini and Böcklin the luminous triad of the greatest priests of that Mediterranean pictorial art that has been and always will be so rich in perfect enjoyments for refined spirits,” and Maurice Denis’s The Pilgrims of Emmaus, which clearly connect to a work by Ardengo Soffici (one of the main ones in the exhibition) featured in the previous room, The Bath of 1905: this large canvas, the only surviving panel of a series made for the Grand Hotel delle Terme di Roncegno, is a formidable synthesis of Puvis de Chavannes’ rigorous simplification of forms and of that aesthetic of the “flat surface covered with colors arranged in a specific order and for the pleasure of the eyes” that Denis himself theorized in 1890 and that had resulted in a simple, linear painting, rich in sharp forms and pure colors that paved the way for the research of French art in the following years. Impossible then not to dwell on the third element of Soffici’s “triad,” Arnold Böcklin, who is present in the exhibition, albeit more dimly than Segantini, Denis and Puvis de Chavannes, with a self-portrait that dialogues with a homologous work by Ardengo Soffici in which the artist, though almost 30 years old, paints himself with a teenage face. Also noteworthy, to close the circle of the “very young Soffici,” are an austere portrait of his mother, the illustrations that the artist executed for French magazines in order to support himself in Paris, and some watercolors with studies of landscapes, animals and various subjects placed on the wall opposite Denis’s Pilgrims.

|

| Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, Les jeunes filles et la mort (1872; oil on canvas, 146.4 x 117.2 cm; Williamstown, Massachusetts, Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute) |

|

| Maurice Denis, The Pilgrims of Emmaus (1895; oil on canvas, 177 x 278 cm; Saint-Germain-en-Laye, Musée départemental Maurice Denis) |

|

| Ardengo Soffici, The Bath (1905; oil on canvas, 199 x 400 cm; Private collection) |

|

| A comparison of Ardengo Soffici’s self-portrait (1907; watercolor on paper, 41.5 x 30.5 cm; Florence, Adriana Galletti Soffici Collection) and Arnold Böcklin’s self-portrait (c. 1893-1895; oil on canvas, 40 x 54 cm; Florence, Uffizi Gallery) |

|

| The wall with Ardengo Soffici’s studies |

|

| Ardengo Soffici, The Bath (1905; oil on canvas, 199 x 400 cm; Private collection) |

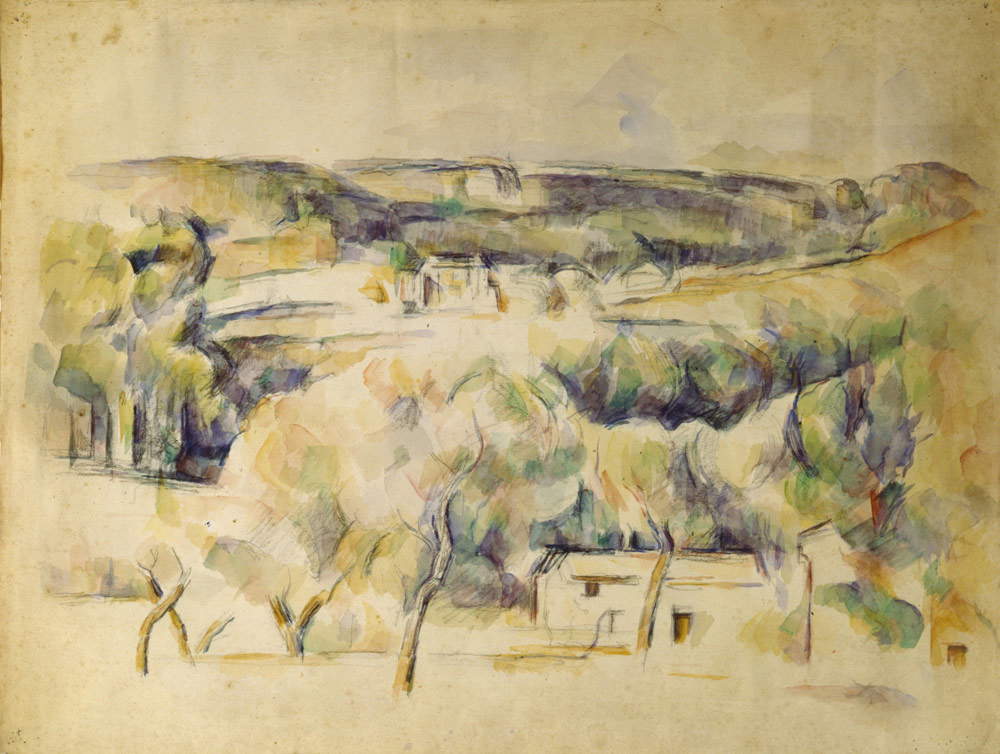

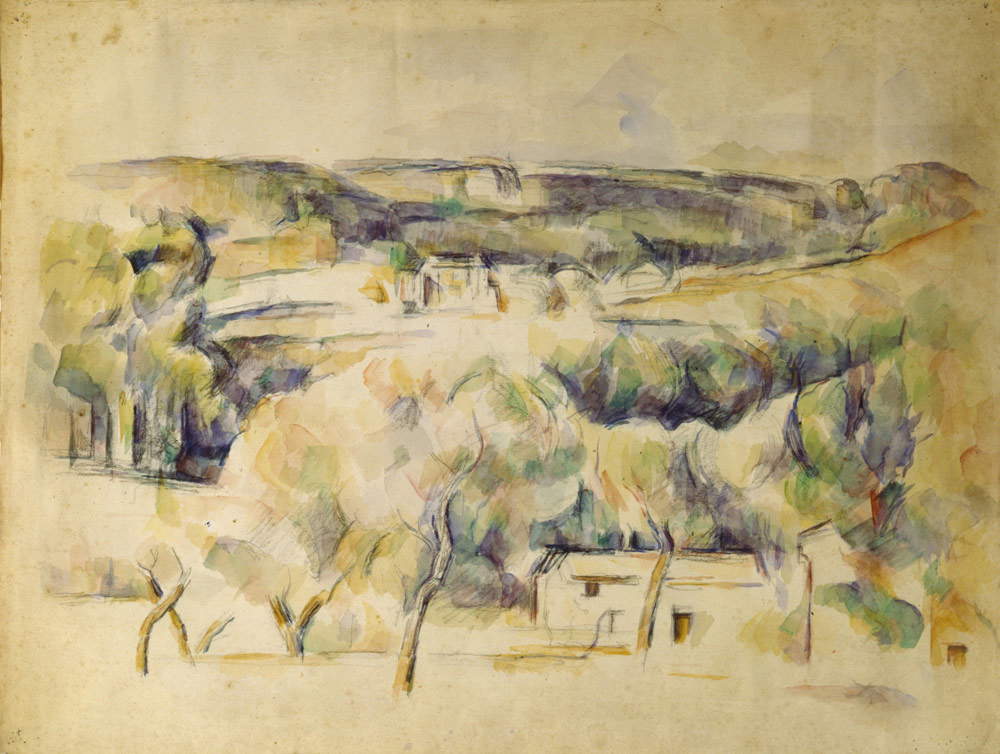

There is a clear, even physical, disconnect between the first section of the exhibition and the next, because the moment Soffici discovers Cézanne his art changes dramatically. However, Soffici is not interested in the intellectual Cézanne, the founding father of all twentieth-century art, the one who would lay the indispensable foundations for virtually all the avant-garde. The young Florentine critic and painter is interested in an intimate Cézanne, the one who manages to capture the essence of the subject with his admirable syntheses arising from a profound sensibility reread by Soffici in a primitivist key: “the primitivism of today accumulates in itself the experience of many centuries, and for those who know how to grasp this character it will not be difficult to grasp in him [that is, in Cézanne] the supreme expression of the modern.” Modern, Cézanne, because he is able to assimilate in his art a tradition that is centuries long, perhaps even millennia long. Soffici is the first in Italy to talk about the French artist, and one of the exhibition’s key junctures is precisely the comparison of some of Cézanne’s works (a Provençal Landscape, a group of Large Bathers, a still life with a cup and a plate of cherries) with a series of paintings by Ardengo Soffici, including a landscape with the Savignone where the artist tries to draw on the syntheses of the great French painter, and a canvas with Card Players, which, besides approaching Cézanne in form, is also close to him in terms of the theme chosen since Card Players are also present in Cézanne’s production (it would have been a real coup to have a specimen of them in the exhibition). Soffici aims to create art out of a contingent, everyday situation (such as a group of old men gathered around a table playing cards), which inspires him to make a real, heartfelt work: the same thing Cézanne did, which is why there is such a distinct affinity between the two.

|

| Paul Cézanne, Provencal Landscape (1900-1904; pencil and watercolor on white paper, 45 x 60.3 cm; Traversetolo, Fondazione Magnani Rocca) |

|

| Paul Cézanne, Still Life with Cherries (1900-1904; pencil and watercolor on white paper, 38 x 49 cm; Traversetolo, Fondazione Magnani Rocca) |

|

| Ardengo Soffici, I giocatori di carte (1909; oil on cardboard, 49.5 x 70 cm; Viareggio, Società di Belle Arti) |

The search for asincere art inevitably passes through one of Soffici’s most daring discoveries, that of the so-called naïf artists, in particular Henri Rousseau, the famous Doganiere with whom Soffici also had a friendly relationship and from whom he asked for some works of art not only because they were, all things considered, interesting objects, but also in order to grasp their essence: and if the representation of Rousseau in the exhibition is somewhat poor (two small drawings, one of a bellboy and one of a woman at the theater), we have from Soffici an extremely significant still life d’après Rousseau. This of the “odd gallery” of uncultured painters, who had not studied in the academies, often could not read or write, and sold their humble works in country markets, is a crucial passage for understanding how Soffici understood art, since he adored, as he wrote in a well-known article in La Voce in September 1910, “that painting which intelligent people say is stupid [....],” that is, that painting “naive, candid and virginal,” the painting “of simple men, of the poor in spirit, of those who have never seen a professor’s mustache.” The artisans were “painters, bricklayers, boys, painters, half-crazy sheepherders, and vagabonds,” like"Fuffa," an unidentified shepherd from Poggio a Caiano who while watching the sheep dabbled in drawing (there are a couple of his sketches in the exhibition), or like Arturo Pezzella, a craftsman who specialized in making very simple store signs, like the one painted for a watermelon maker and in exchange for which Soffici would have gladly given “the Madonna of the Harpies by Andrea del Sarto, the Assumption by Murillo, and all, all the work of Fra’ Bartolomeo.” for the Tuscan critic-painter, in short, a painting that is banal but true and the exclusive fruit of the soul is worth more than a celebrated but classicist altarpiece to the point of bordering on devotion.

|

| Ardengo Soffici, Natura morta d’après Rousseau (1939; oil on canvas, 38 x 46 cm; Private collection) |

|

| Arturo Pezzella, Insegna di cocomeraio, detail (1908; oil on canvas, 109 x 78.5 cm; Florence, Private Collection) |

So many discoveries had to be somehow divulged to the Italian public: thus it was that, in the spring of 1910, Soffici did his best to organize, in Florence, the first exhibition of the Impressionists in Italy. The two small rooms that evoke this exhibition are to be applauded: philologically punctual, in these rooms we are presented with paintings on the one hand, and sculptures on the other. In the first small room there is a landscape by Cézanne, there is a Promenade by Toulouse-Lautrec, there is a gem like Camille Pissarro’sApproaching the Storm, the impressionismo-francese-prima-volta-in-italia-1878.php' target='_blank'>first Impressionist work ever seen in Italy and at the time, that is, in 1878, greeted with almost unanimous disdain, there is a splendid Child Portrait by Renoir (the portrait of his son Pierre) that fully demonstrates why the latter was probably Soffici’s favorite Impressionist: for although his painting was essentially that of a “modest workman decorator of majolica,” in his “youthful and spring-like” imagery one can find “the same happiness of giving to the most real detail the large and broad imprint, the definitive originality of the work of art not transitory but unalterable in time.”

The second room, on the other hand, offers visitors a selection of works by Medardo Rosso: there were seventeen, the Turin artist’s sculptures exhibited in Florence in 1910. An artist from Turin who, although he could enjoy a certain success in Paris, remained almost unknown in Italy, and Soffici has the merit of introducing him for the first time in a complete way to the Italian public with this series of works, among whichEcce puer (actually a portrait of an English child, Alfred Mond, which “by its character of grandeur infinitely transcends the conditions imposed on the portrait , to become like a symbolic depiction of the human, irrespective of the accidents of race, sex, and age”) and that Portinaia, which represents one of the highest peaks of Impressionism in sculpture, being one of the first examples in Rosso’s art (and in Impressionist sculpture in general) in which the figure begins to merge and blend with its environment.

|

| Paul Cézanne, Campagnes de Bellevue (Landscape) (1885-1887; oil on canvas, 36.2 x 50.2 cm; Washington DC, The Phillips Collection) |

|

| Camille Pissarro, Landscape-The Approaching Storm (1878; Florence, Galleria d’Arte Moderna di Palazzo Pitti) |

|

| Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Child Portrait (1885; oil on canvas, 42 x 35 cm; Turin, GAM) |

|

| Medardo Rosso, Ecce Puer (c. 1908, from a 1906 model; bronze, 45 x 34 x 24 cm; Venice, Galleria internazionale d’Arte moderna di Ca’ Pesaro) |

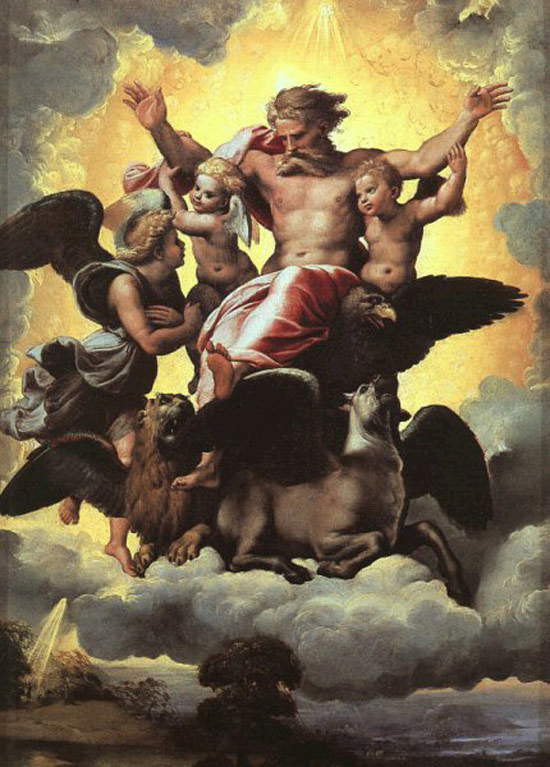

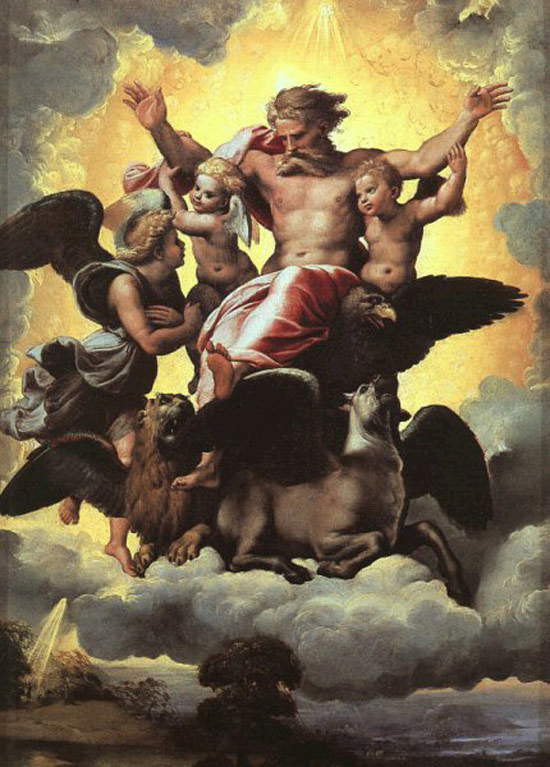

On a par with the “discoveries,” the “massacres” of course continued, and indeed became perhaps more intense, especially at the 1910 Venice Biennale, when Soffici mercilessly crushed artists such as Giulio Aristide Sartorio (who proposed, according to the critic, a “slummed hall” with a “saraband of naked or veiled bodies, the same epileptic attitudes, the same expressionless faces, the same lack of drawing, style, poetry and life.” we have an example of this in the exhibition with one of the Caryatids) and Franz von Stuck (his would be a “painting made by theft,” lying to the point of being “most dangerous and deleterious”), but saves instead Gustave Courbet to whom the Biennale, that year, dedicated a retrospective: Courbet’s merit was that of having stripped his art of any residue of classicism and of understanding that the first “piece of earth or sky that happens to be is good, as long as it is seen with emotion and transfigured by imagination.” The adjoining room is thus connected to this discourse: the release, at that time, of a monograph by Maurice Barrès dedicated to El Greco is an opportunity to reflect on the poetics of the great Hellenic artist, who in the Florentine exhibition is placed alongside Raphael’s celebrated Vision of Ezekiel. For Soffici, hostile to all idealisms, El Greco was one of the greatest in the history of art insofar as he was not subjugated “by the octopus that was already suffocating Italy,” that is, the adulation of the greats of the Renaissance and classical antiquity, thus insofar as he was able to avoid “losing his own original and genuine temperament in order to be enlisted in the immense band of courtiers worshippers of Michelangelo’s Sibyls [...] and of Raphael’s glorious and insulting classicism and Catholicism.”

|

| Franz von Stuck, Medusa (1908; oil on panel, 72 x 83 cm; Venice, Ca’ Pesaro International Gallery of Modern Art) |

|

| Gustave Courbet, Le Grand Pont (1864; oil on canvas, 97 x 130; New Haven, Connecticut, Yale University Art Gallery) |

|

| El Greco, Saints John the Evangelist and Francis (c. 1600; oil on canvas, 110 x 86 cm; Florence, Uffizi Gallery) |

|

| Raphael, The Vision of Ezekiel (c. 1518; bronze, 40.7 x 29.5 cm; Florence, Palazzo Pitti, Galleria Palatina) |

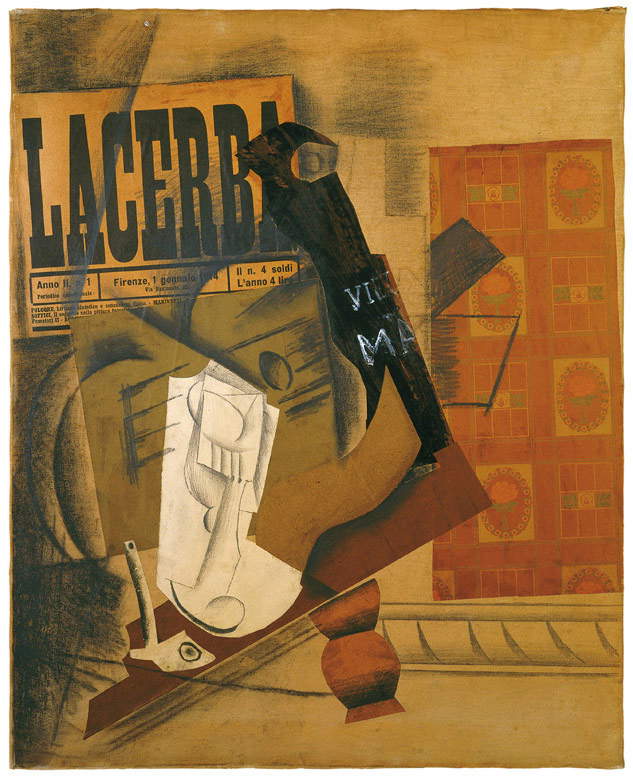

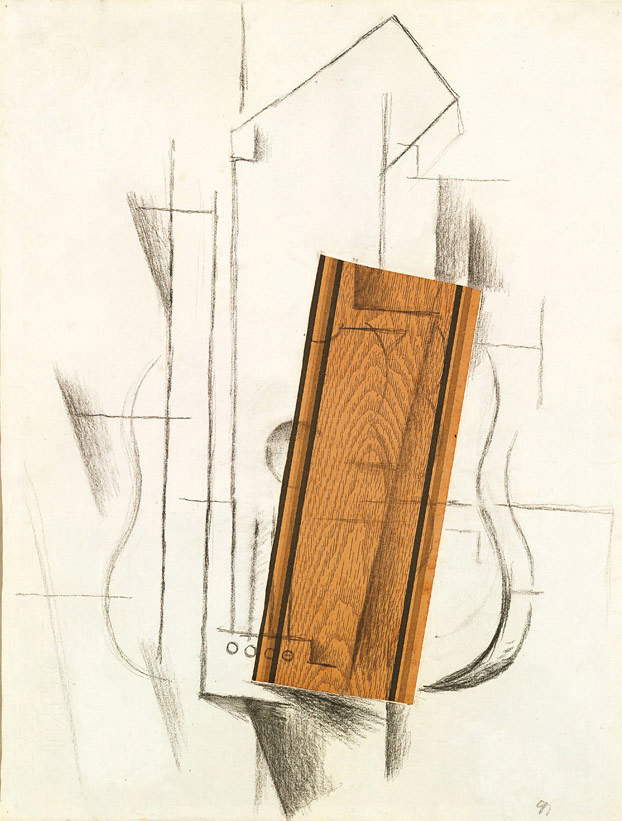

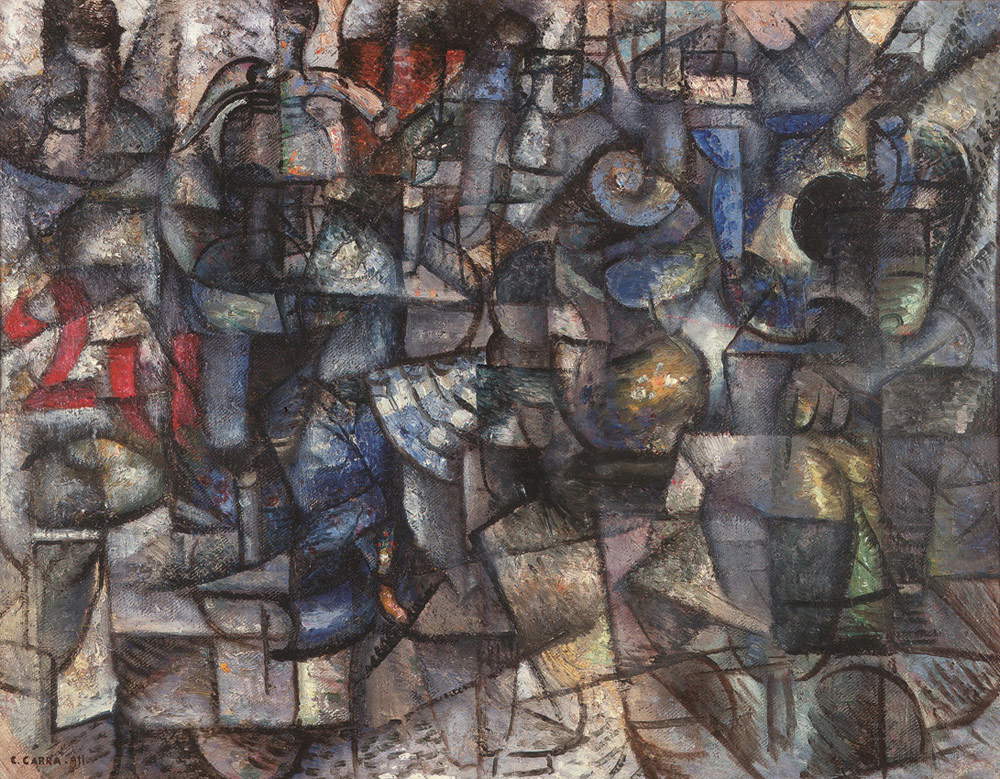

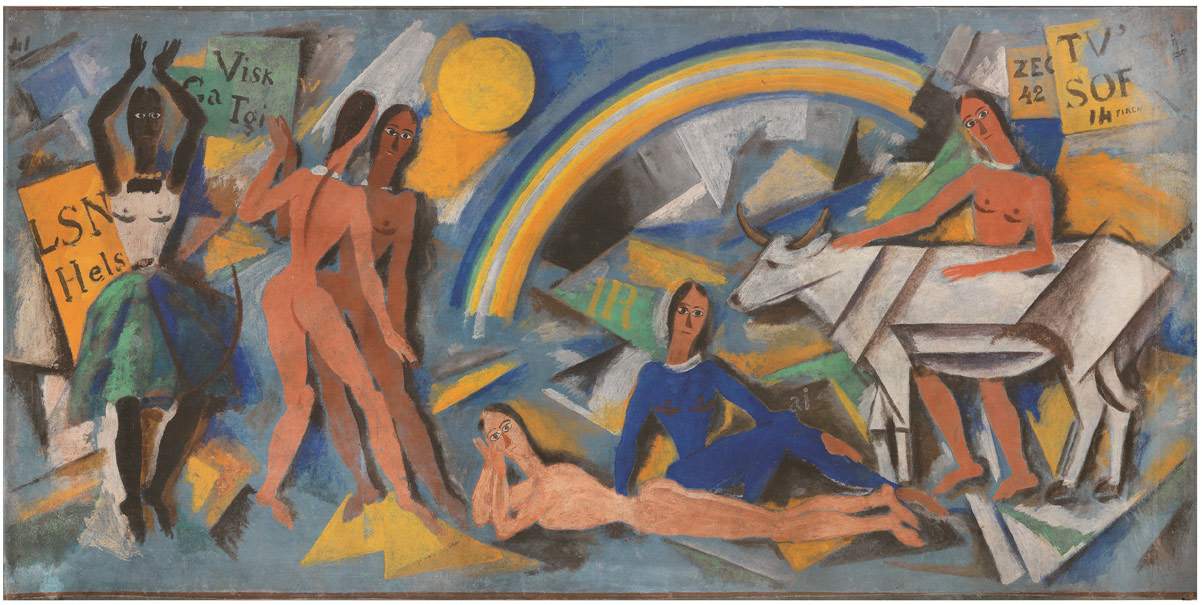

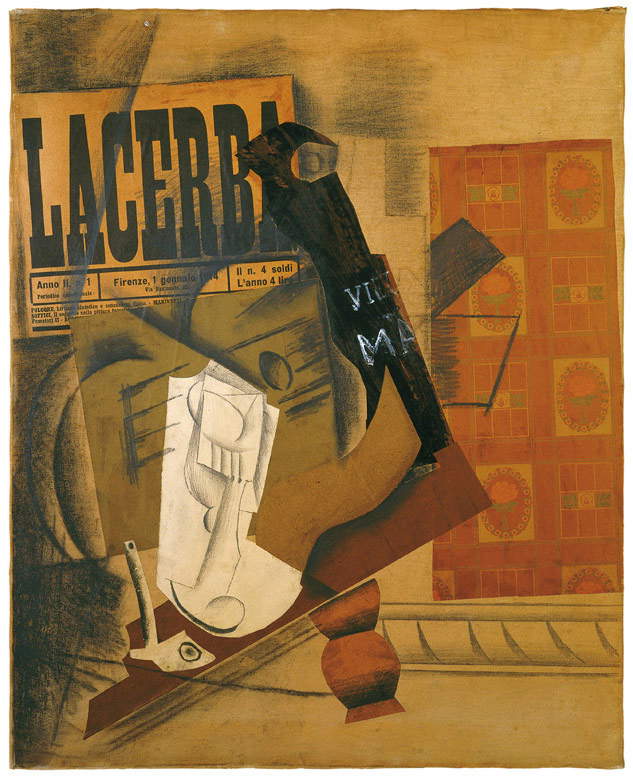

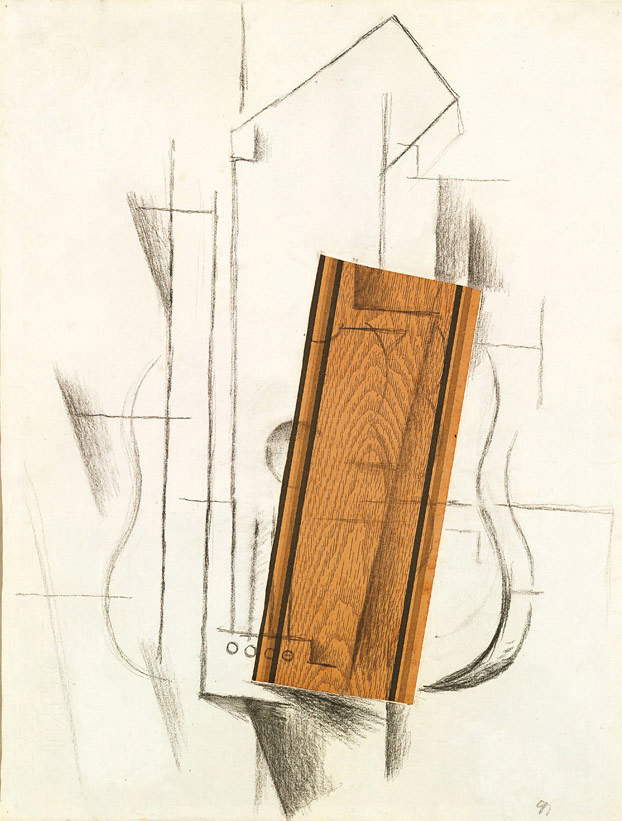

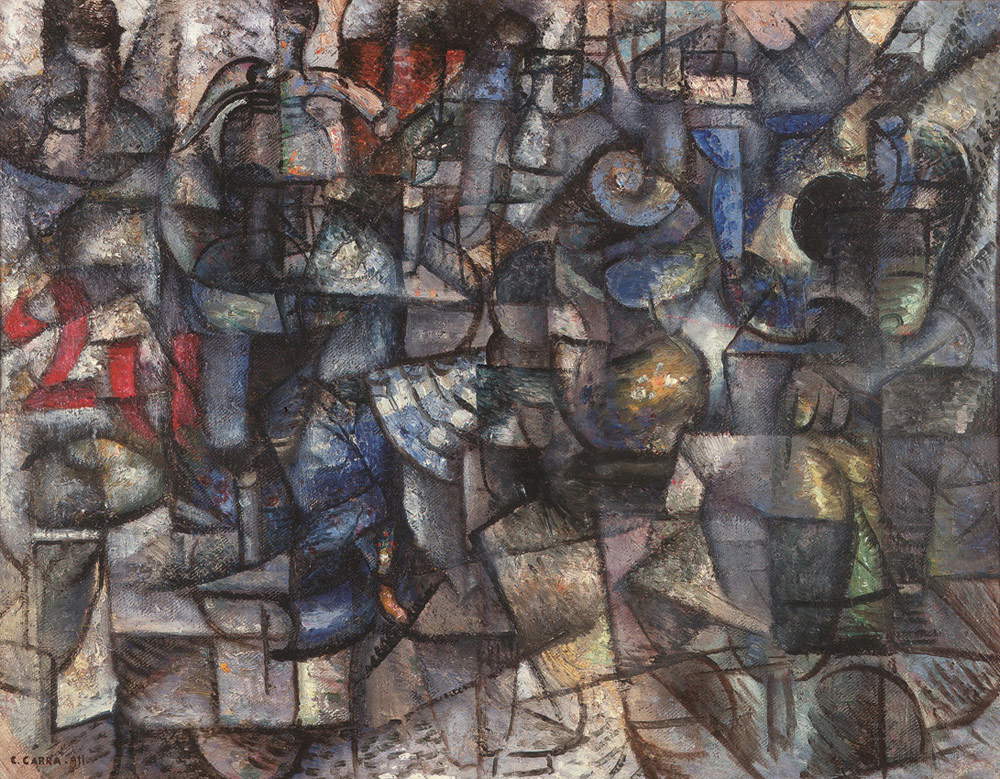

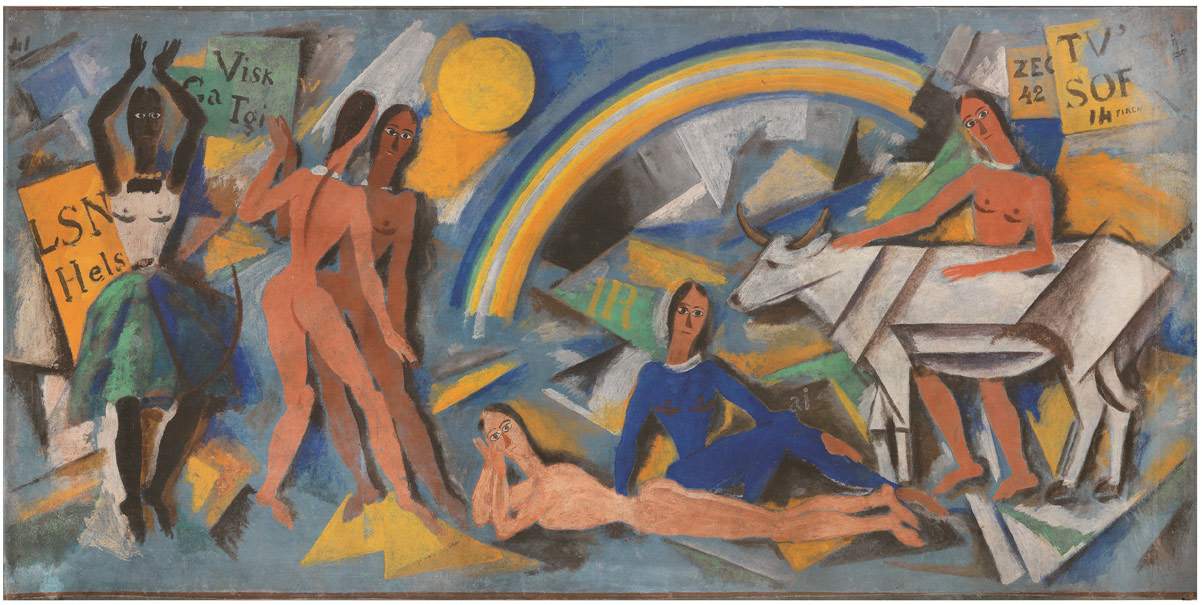

Immediately following is Soffici’s new and last great discovery: cubism, represented in the exhibition by a number of works by Braque and Picasso. Of the Spanish painter, in particular, Soffici would become a good friend, and Picasso would reciprocate the esteem by inserting, in one of his works belonging to the phase of synthetic cubism, the header of Lacerba, the magazine that Soffici had founded in 1913 together with his lifelong friend, Giovanni Papini (the work is present in the exhibition). And if the admiration for Picasso and colleagues is clear and peaceful, more difficult are the relations with the Futurists, whom at first Soffici terribly crushes in probably his most famous review, the one dedicated to the Boccioni exhibition, Carrà and Russolo of 1911 in Milan (“foolish and laid blunders of unscrupulous messers, who seeing the world turbidly, without a sense of poetry, with the eyes of the most pachydermic pigmy of America, want to make believe they see it blooming and flaming, and they believe that the whiffing of color by madmen on a painting by janitors of the Accademia, or the retiring in the piazza of the lint of pointillism, this dead Segantinian error, can make their game succeed in the sight of the sucker crowd.”), also attracting a punitive expedition that the three artists organized in Florence provoking a brawl at the Caffè delle Giubbe Rosse, and with whom he then began to have relations to the point of welcoming futurist elements into his art. Soffici thus becomes a Cubofuturist in whose paintings (in the exhibition we have, for example, a Synthesis of an Autumn Landscape, to be compared with Carlo Carrà ’s Rhythms of Objects ) the analytical Cubist intellectualism is never quite overwhelmed by the typically Futurist sense of movement. A admirable synthesis of these experiences is another (the last, probably) of the exhibition’s key points: the perfect reconstruction of the decorations of the Sala dei Manichini, a room in Giovanni Papini’s house in Bulciano (a Tuscan village near the border with Romagna), which had been decorated by Soffici with a frenetic dance of nudes that assimilates primitivism, decomposition, and Futurist dynamism. A summation of all the experiences of the critic and all the artists he had “discovered” and made discover to the public.

|

| Pablo Picasso, Pipe, glass, bottle of Vieux Marc and “Lacerba” (1914; paper collage, charcoal, India ink, printing ink, graphite and gouache on canvas, 73.2 x 59.4 cm; Venice, Peggy Guggenheim Collection) |

|

| Georges Braque, Still Life with Guitar (1912; charcoal and collage on paper, 62.1 x 48.2 cm; Milan, Museo del Novecento, Jucker Collection) |

|

| Carlo Carrà , Rhythms of Objects (1911; oil on canvas, 53 x 67 cm; Milan, Pinacoteca di Brera) |

|

| Ardengo Soffici, Synthesis of an Autumn Landscape (1912-1913; oil on canvas, 45.5 x 43 cm; Prato, Farsetti Arte) |

|

| Ardengo Soffici, Two Panels from the cycle of the Stanza dei Manichini at Casa Papini in Bulciano (1914; wall temperas detached and transferred to panels; Florence, private collection) |

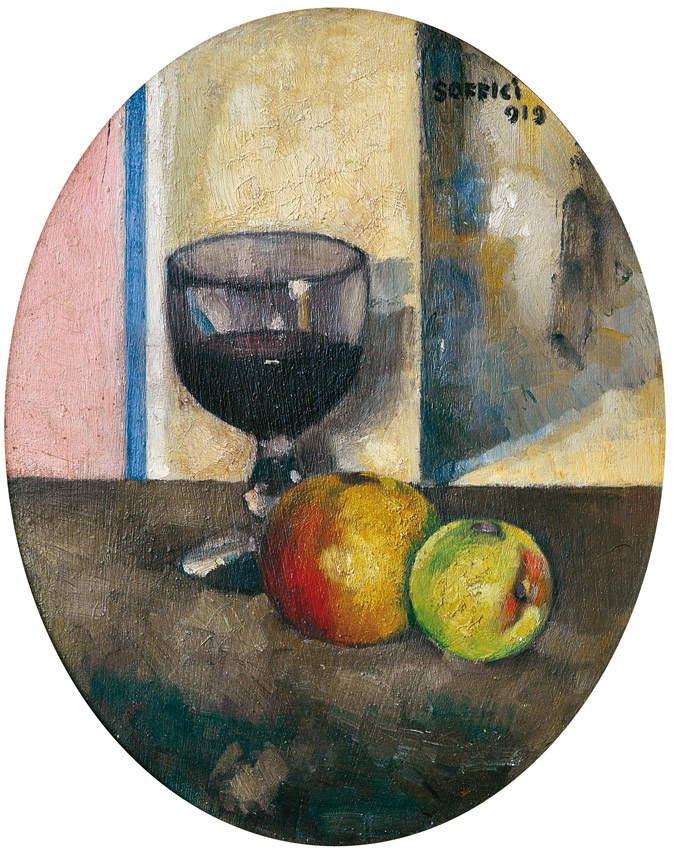

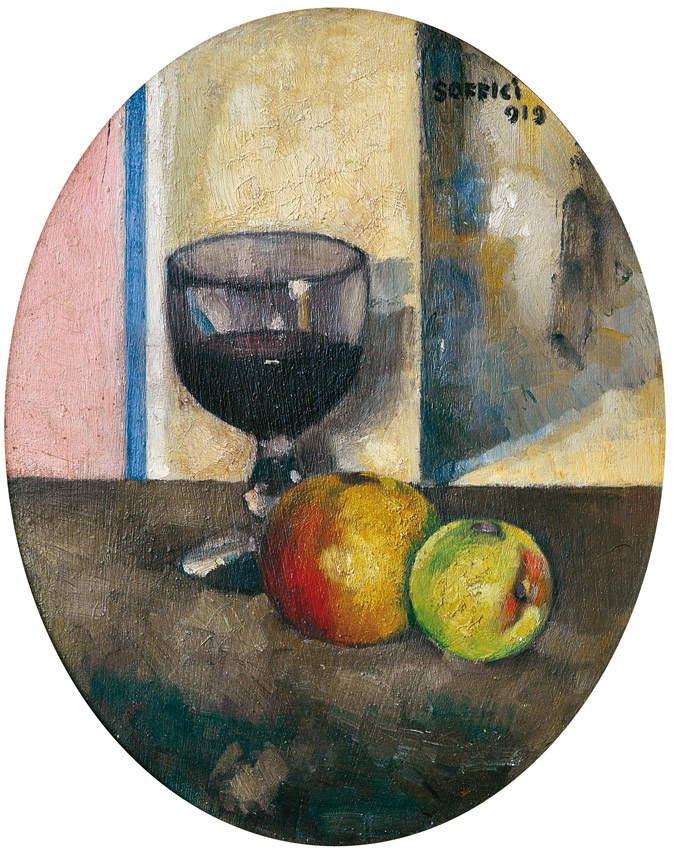

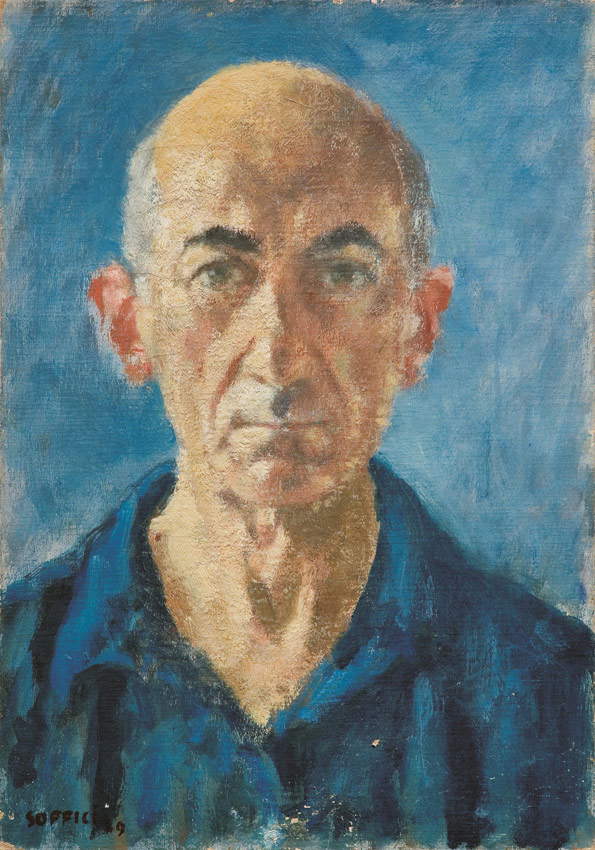

The last two rooms of the exhibition, the most tired of the entire itinerary, which come after a kind of significant leap into the void (they are separated from the one dedicated to Cubism by a long narrow black corridor) close the doors on the most interesting Ardengo Soffici. On the threshold of World War I, the painter-critic became an ardent interventionist and then, following Italy’s entry into the war, he went to the front as a volunteer, suspending all art-related activities (except for the conception of a satirical trench newspaper, La Ghirba, for which he availed himself of the collaboration of Carrà and a young Giorgio De Chirico, which represents his last “discovery,” if we exclude some insights from the latter part of his career, in any case not addressed by the Uffizi exhibition: one name above all, that of Ugo Guidi) and returning from the war tried, completely changed and an advocate, among many others, of that return to order that in his painting is substantiated in some works completely devoid of the avant-garde mordant that had marked not only his criticism but also his art. The last gasp of the exhibition (beyond the display of the self-portrait donated to the Uffizi by the heirs: a donation that was the occasion for organizing the exhibition) is a comparison between a landscape by Soffici made in Poggio a Caiano and another landscape, identical, painted, however, by Ottone Rosai, which shows us not only Soffici’s renewed will (to find order and stability again) but also how the artist was beginning to be looked upon as a model.

|

| Ardengo Soffici, Apples and Glass of Wine (1919; oil on panel, 42 x 33 cm; Viareggio, Society of Fine Arts) |

|

| Ardengo Soffici, Self-Portrait (1949; oil on cardboard canvas, 50 x 35 cm; Florence, Gallerie degli Uffizi, Galleria delle Statue e delle Pitture) |

One leaves the exhibition with the feeling of having visited one of the most interesting operations of the year. An exhibition in which there are no punchlines: if we really want to be punctilious, we point out just the last two rooms whose level of involvement is not equal to all the others that precede them, a few regrets for some absences (not enough is said about Soffici’s formation under the sign of the Macchiaioli, but it is in any case unimportant to the underlying discourse of the exhibition, and then, as mentioned above, paintings by Rousseau are missing), and perhaps a communication that struggles to appeal to an audience unaccustomed to this kind of exhibition (and which becomes most unfortunate when Soffici is called a “wrecker” the term, used by Schmidt in interviews on the sidelines of the opening, could well have been avoided, given its political overtones in recent years). It seems that the exhibition trudges in addressing the “Uffizi audience,” but it must also be said that the visitor, once intrigued and “captured,” becomes fully involved also because the curators had the great merit of making rather easy reading of subjects that we would usually imagine reserved for specialists. The judgment, in short, is far more than positive: this is an exhibition that is certainly complex but at the same time clear, that does not limit itself to reconstructing the features of a single figure, that of Ardengo Soffici (an error into which a monographic exhibition often runs the risk of falling), but that reconstructs with great precision the context of reference that, indeed, in certain passages even takes over from the protagonist (at the beginning, for example: but it could not, after all, be otherwise). And an exhibition that also has the merit of having reconstructed the articulate personality of Ardengo Soffici by moving along two tracks: the critic and the painter. Managing to reconcile these two aspects of one of the most important figures of the early 20th century was an operation with an outcome that was anything but obvious. Finally, a note on the catalog: beyond the (very rich) entries and the apparatus, we have only an introduction and a couple of essays, one dedicated to the Discoveries and the other to the Massacres, signed respectively by Nadia Marchiori and Vincenzo Farinella, which take the shape of “anthologies” of Ardengo Soffici’s critical production. Contributions intended more for the public than for specialists: and perhaps that is a good idea.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools.

We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can

find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.