The public about to enter the National Gallery of Modern and Contemporary Art in Rome has been queuing for seven years amid Davide Rivalta’s lions, guardians against passatism, imperious felines ready to roar against everything that smacks of the rancid, incendiary beasts eager to open their jaws wide against dust, mold and old age, to maul the glorious old canvases, to reawaken the public dormitory of painters and sculptors resting among those halls. Hic sunt leones, or so it should have been: the lions’ mission was to signal to the public the presence of the unexplored territories of art beyond the museum doors. And instead they stand there, rolling heedlessly on the Gallery’s steps, harmless and inoffensive as they now gaze at the banners of the exhibition The Time of Futurism , which, far from venturing into the desert dunes, prefers to stroll in the flowery safety of the well-tended, well-watered, well-cultivated garden. Gabriele Simongini, the curator, made no secret of this at the press conference: The Time of Futurism is meant to be an exhibition for everyone, suitable for a wide audience, from the “most avid bibliophile” to the “child who seeks technological novelties,” from the “contemplation enthusiast” to the multimedia installation buff. The new features, he assured, will be in the catalog and will mainly concern the 1909 Manifesto (with unpublished interpretations by Giovanni Lista) and the theme of the Futurist spectacle (with new data in a dialogue between Lista and Günther Berghaus). The catalog, at the moment, is not yet available: to evaluate the exhibition without letting too much time pass, it is then necessary to refer only to the tour route. And here, on the contrary, no novelty, no substantial novelty: a user-friendly futurism has been preferred, we could say paraphrasing the curator, an exhibition “that is not made only for insiders,” he said, “an exhibition that has the main purpose of making people understand the revolutionary scope of futurism and its links with life then and now: I am proud to make an exhibition for everyone.” The “links with life today,” it will come to us, are to be found, according to the idea of the exhibition, in the relationship between futurism and science, between futurism and technology.

Would Marinetti have liked a “futurism for all”? Would he have liked a futurism among Corinthian columns and whitewashed halls? Would he have liked his revolution to be accessed with a Roma Pass tourist ticket? However, the question about whether he would have liked Marinetti, which resounds stentorianly in these hours especially among cultural circles hostile to the government, seems idle: the fate of every avant-garde after the sunset is to become bourgeoisie or history, or both, and in any case to become past (not to mention, then, that our attitude toward the past has undergone, in the last hundred years, some minor modification). Indeed, the Marinetti of the early postwar period would perhaps have admired the activism of former minister Sangiuliano: political revolution, Marinetti wrote in the manifesto The Artistic Rights Advocated by the Italian Futurists, “must support the artistic revolution, that is, futurism and all the avant-gardes.” Sangiuliano must have taken Marinetti’s intentions to the letter, since since his inauguration at the Collegio Romano he has long labored to support, promote, plan, organize, and launch a major exhibition on futurism, dreamed of from the very first public outing (it was October 29, 2022, barely a week after his appointment, and already Sangiuliano was fantasizing about a futurist exhibition, perhaps to be set up ... in the halls of the National Archaeological Museum in Naples!), with a participation in the definition of the contents of a museum that has no precedent in the history of the country, and that began to take shape in December two years ago, with the official conferment of the task to Giuseppe Simongini. Everything that came after that is well known, and it seems senseless to dredge up here all the controversies that accompanied the preparations for the exhibition (to the observation, which emerged during the press conference, that even the aftermath of controversy evokes a futurist climate, it is in any case worth responding that the futurists sought out, raised, and planned the controversy with millimetric precision: it is not that they suffered it as happened to the Gnam exhibition), because the shadow that lurked in the newspaper columns became flesh, the fantasy turned into substance, the dream became reality, and the exhibition has finally arrived, open to all, open to the appreciation of enthusiasts (which will not be lacking), open to discussion and criticism, ready to be debated and weighed, with its pachydermic load of materials (five hundred objects, of which three hundred and fifty works of art, arranged along twenty-six rooms!) and with the equally gigantic load of expectations, further fueled by Renata Cristina Mazzantini, director of Gnam, who in a press conference even presented it as a literally epochal review, namely as what is “perhaps the most important exhibition of the last ten years in Italy.”

How then is the importance of an exhibition assessed? The quantity of pieces arranged along the visiting itinerary is not enough (and this is clear to everyone, even to those who have never set foot in a museum), there is no need to remark on the internationality of the loans, and often it is not sufficient even for the quality of the works that make it up if key pieces are missing from the roll call, if the project is unclear, if certain readings seem forced, if the apparatuses are meager, if there is a lack of substantial novelty, a lack of fresh looks, a lack of new ideas. If, therefore, one must evaluate Il tempo del Futurismo on the basis of its importance, there are at least a couple of exhibitions in Rome right now that are certainly more important, namely the one on the Ludovisi papacy at the Scuderie del Quirinale and the one on the relations between Giambattista Marino and the arts at the Galleria Borghese, i.e., two exhibitions based on effectively new projects, dense with relevant works and juicy international loans, which delve into topics that have been little or not at all explored (if not in literature, certainly in the exhibition field). But the importance of Il tempo del Futurismo must also be scaled down with respect to the history of exhibitions on the movement, a history that is, moreover, dense, especially in recent years: the stereotype of a futurism rejected by the Italian cultural milieu because of its ties to fascism must be strongly rejected. It was, of course, for a long time, but the demolition of the barriers erected by the damnatio memoriae began more than thirty years ago and today we speak of futurism exactly like sixteenth-century mannerism or Venetian Vedutism, that is, like a moment in the history of art. And in this respect the exhibition, despite the events that accompanied it (at the beginning of November the Culture Commission, in responding to a question by Congresswoman Manzi, did not hesitate to point out that the reduction in the number of works originally planned - were to be about six hundred - was decided “by Professor Simongini himself with the political leadership of the Ministry and with the management of the National Gallery of Modern Art”), it should be emphasized, avoids ideological or political claims, and this is no small merit. With respect to the history of exhibitions of futurism, it was said, there have been even in the very recent past some more intense and important moments, even without having to go back too far: more original than the Gnam exhibition were, for example, the review on aeropainting at the Labirinto della Masone, or even the one at Palazzo Blu in 2019, which traced the history of futurism (the entire history of futurism, as the Guggenheim’s review in New York a few years earlier had done, for the first time in a comprehensive way) with chapters related to the various manifestos that punctuated the history of the movement, or even last year’s first monograph on Gino Galli, which had the merit of drawing attention to a luminous pupil of Balla who had remained too long covered in the ashes of oblivion.

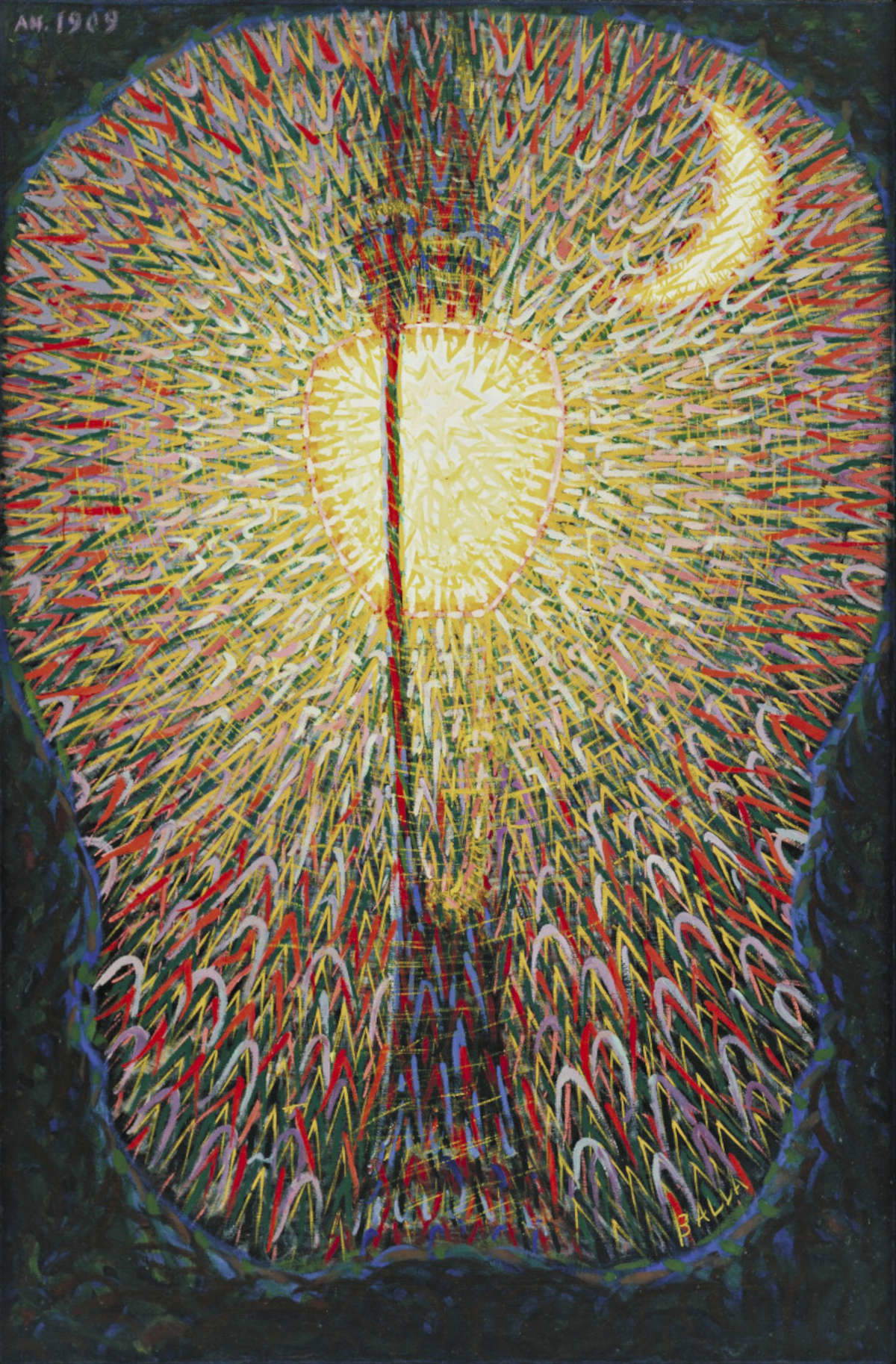

What then should the public expect? An exhibition that could be described as scholastic is being staged in the halls of Gnam. A summary exhibition, to be generous. A chronological, paratactic, minimalist, conventional scan, devoid of jumps. An exhibition that is also lacking in the intent of being an exhibition for everyone, because the apparatus is reduced to the bare minimum, the few panels that mark the path are stingy with information, and moreover I was told by a Gnam employee that not even the possibility of listening to an audio guide is allowed: an exhibition for everyone, in short, that in fact almost abandons its audience. Not that there is a lack of important pieces, but for being the most important Italian exhibition of the past decade, the absences are many: compared to the canon of the four fundamental paintings established by Pontus Hultén at the unrepeatable Palazzo Grassi exhibition in 1986, only one can be seen at Gnam (Russolo’s Revolt , a truly exceptional loan nonetheless, which together with Balla’s Lampada ad arco is perhaps worth theentire visit), missing extremely relevant texts such as Boccioni’s Rissa in the Gallery and Footballer , Balla’s Dog on a Leash and Violinist , Russolo’s Perfume , some key works from theaeropittura (such as Tullio Crali’s Incuneandosi nell’abitato ), the sculpture is almost totally unaccounted for, the only, scattered pieces representing Bragaglia’s Photodynamism are lost in the two rooms reserved for Futurist advertising, they are not in chronological agreement with the rest of the exhibition, and the public, finding them amidst volumes, writings and articles, risks underestimating their relevance. Simongini, in his essay in the catalog, screens himself in advance, branding as a “rather cloying game” by “insiders” the counting of absences (“this work is there but that one is missing”), but this count perhaps becomes more than legitimate for an exhibition that opens after months of proclamations, presented almost as the event of rebirth, as a “relevant project [...] for the National Gallery itself, which after years has returned to host an exhibition with an international scope.” Wishing for the presence of the founding texts is not specialist onanism: it is usually what is expected of an exhibition that has ambitions of relevance.

This, of course, does not mean that there is a lack of important pieces: judgment should not overstep in the opposite direction, either, not least because the beginning of the itinerary is indeed bombastic, with a refined first room evoking the premises of Futurism with a small but very dense string of cornerstones of pointillism, with Pellizza da Volpedo’s Sun and Sunset and Segantini’s Alla stanga , among others, dialoguing with Balla’s Lamp ad arco : it is as if the exhibition begins by telling the audience that at the dawn of the twentieth century a rural Italy, tied to the rhythms of nature, was about to succumb in the face of the onset of modernity, the hubbub of cities, the Italy of electric light. Pellizza’s natural light sets, Balla’s artificial light rises, which should illuminate the rest of the way from there on. It is a dense, powerful beginning that accompanies visitors to another room where the works of the Futurists before Futurism, of other great Divisionists (Previati above all) and of some notable forerunners, above all that Romolo Romani present at the beginning of the itinerary with the Portrait of Dina Galli and above all with The Scream suspended halfway between Symbolist reminiscences and anxiety of modernity.

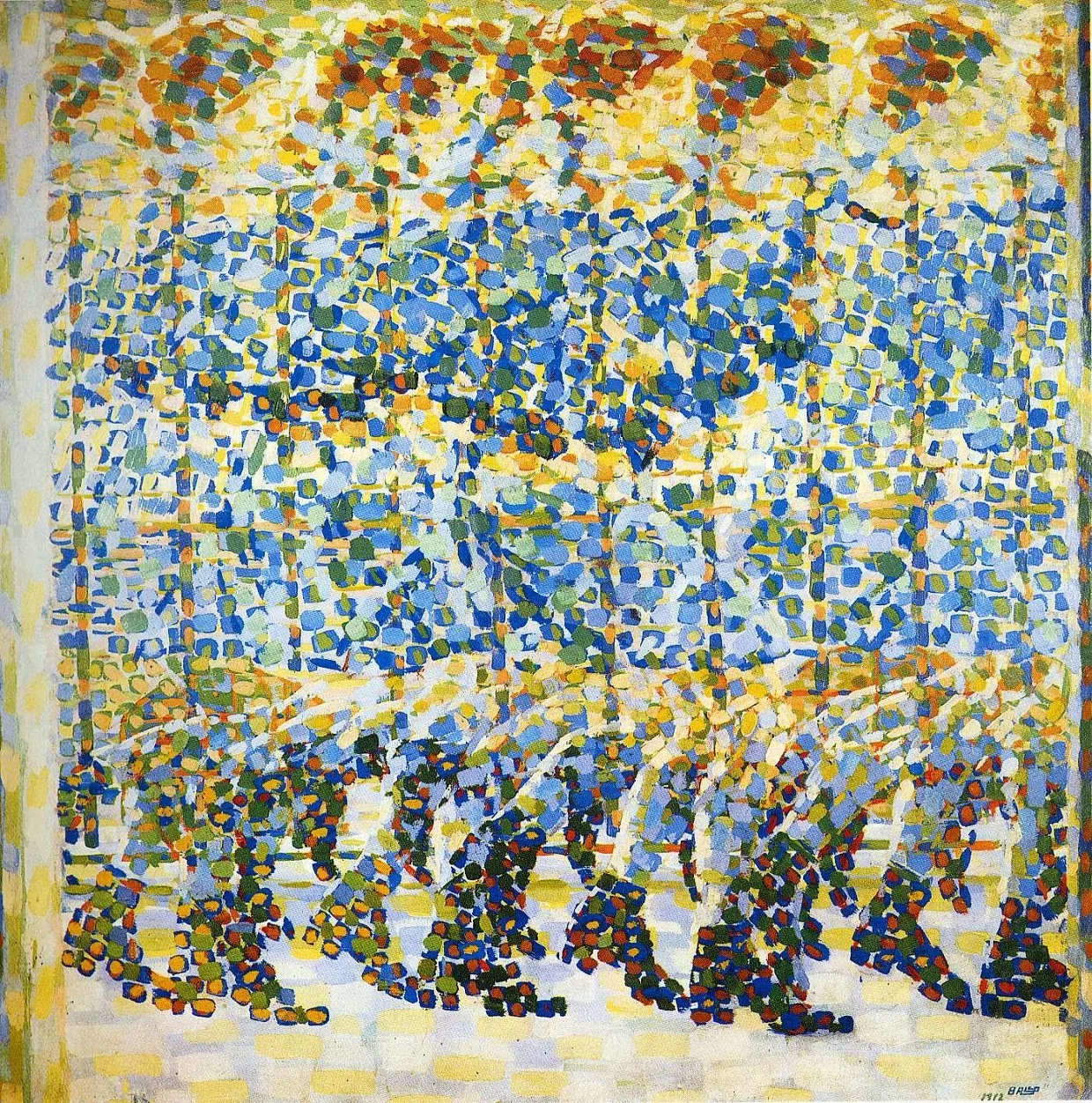

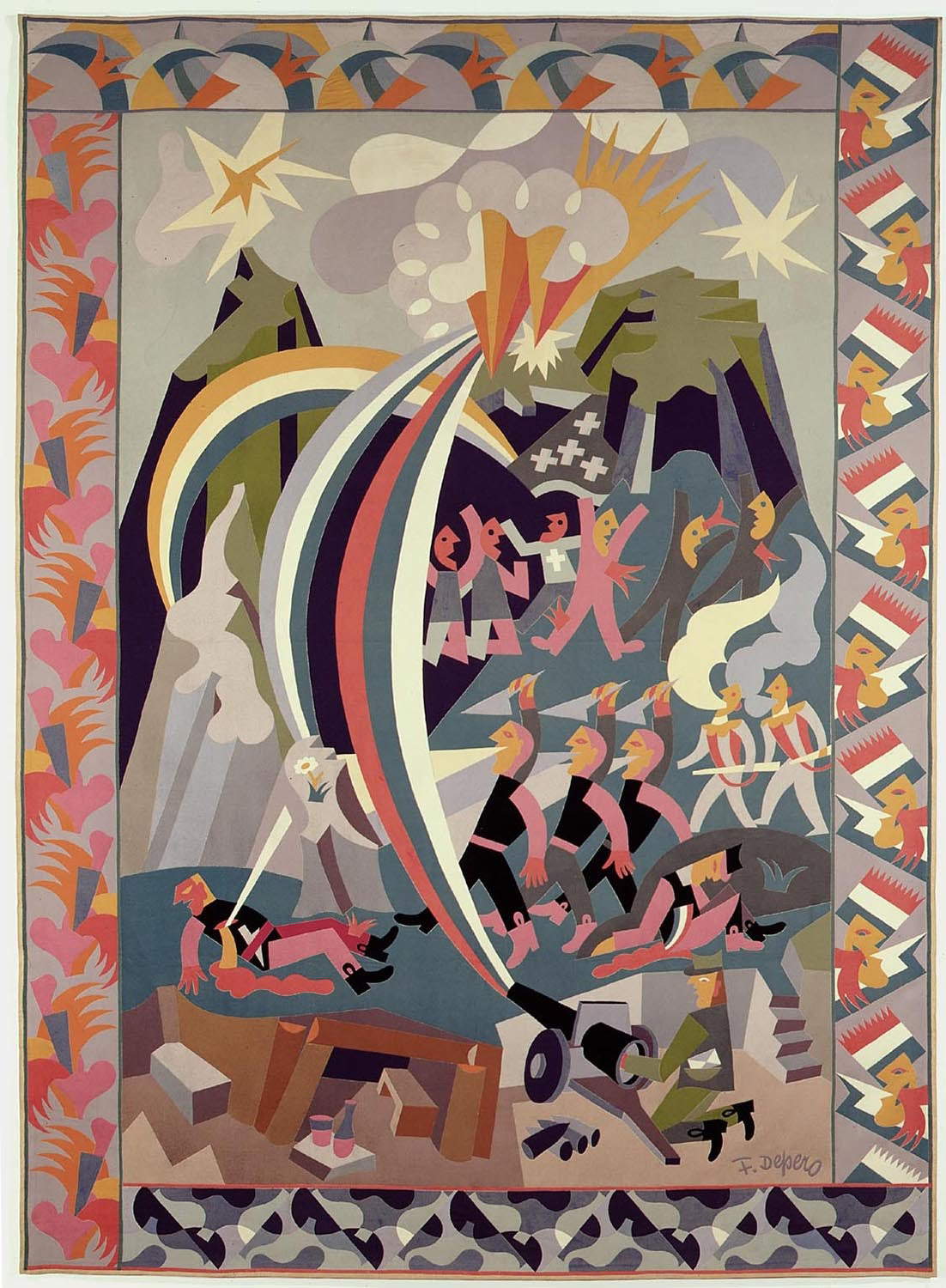

Then, after the deflagration, the exhibition begins to lose strength, vigor, intensity, undergoes some chronological displacement (not only the Bragaglia out of time: the most obvious is the parade of automobiles in a room where there are still manifestos of pointillism and symbolism, starting with Previati’s Caduta degli angeli from 1913 displayed behind a Maserati model that came out fifteen years after Previati’s death), and meets with a dilution that is inescapable in an itinerary that is made for a large part of pieces pulled out of the Gnam deposits: even here there is no shortage of surprises that are worth the visit (Balla’s Futurlibecciata that evokes oriental atmospheres, or Farfa’s Geographical Portrait of Marinetti , or even Ivo Pannaggi’s Architectural Function , an advocate, in the second wave of Futurism, of an alternativean alternative machinism with strong political implications), but the fact that one-third of the exhibition, roughly, is composed of works that are part of the collection of the host museum and especially of its deposits (and much focus on Balla’s production and the two concluding sections on thelegacy, or presumed legacy, of Futurism), in spite of the sincere enthusiasm it arouses for the possibility of seeing pieces that would otherwise be difficult to admire, it is a circumstance that causes an inevitable watering down, with the fundamental pieces that get lost among the many outlying works and, also complicit in the absence of a panel system that can guide the visitor, risk passing unnoticed. Drowned in the waves of a flat didactic apparatus, despite the claims of inclusiveness, are the Futurist Synthesis of War, Giuseppe Cominetti’s Can Can (who was among the most moving of the Divisionists and who was also a Futurist for some brief time), two small iridescent Compenetrations by Balla (which far from being thebeing the best of the series are nevertheless the only witnesses in the exhibition to this strand of the Roman futurist’s researches, who with the Compenetrations posed himself as one of the first European abstractionists, and according to recent interpretations his abstraction even preceded that of Kandinsky), the Speed of speedboat by Benedetta Cappa Marinetti and Marisa Mori’s Battaglia aerea nella notte (the contribution of the futurist women to the movement has been neglected, despite the fact that more recent research has begun to pose the problem, as seen in the exhibition at the Labirinto della Masone), the mechanical and animal dynamism of Gino Galli whowas an original and long-neglected interpreter of early Futurism, Ardengo Soffici’s Natura morta collage innervated with French sap, or even the two sheets by Guido Strazza, the only Futurist still living, almost hidden in the section on aeropittura.

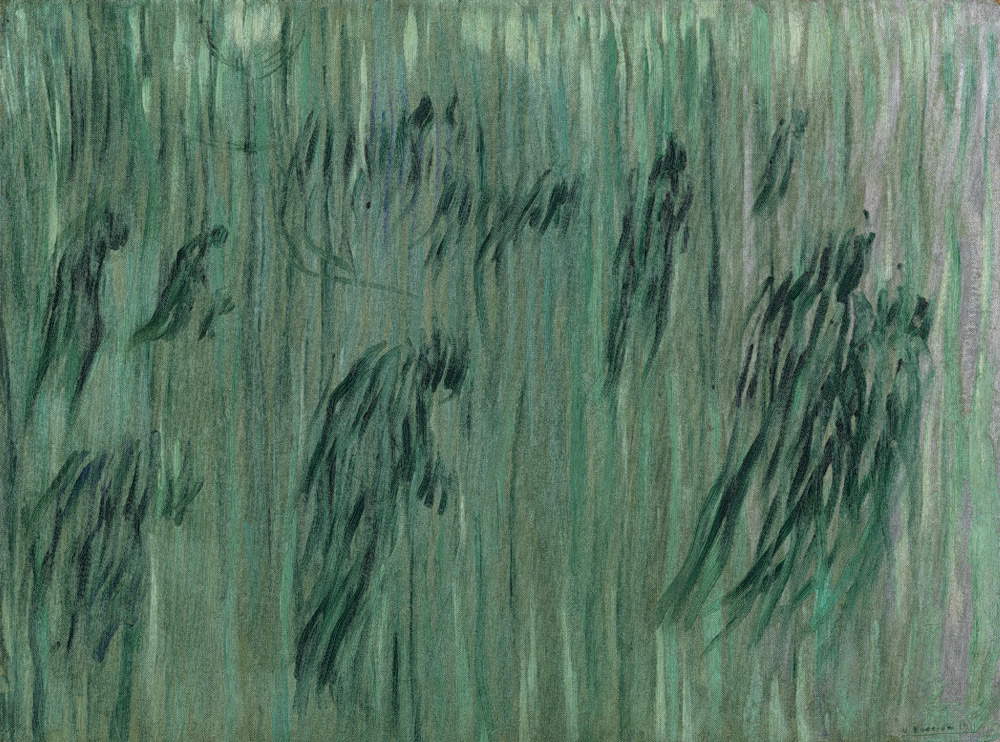

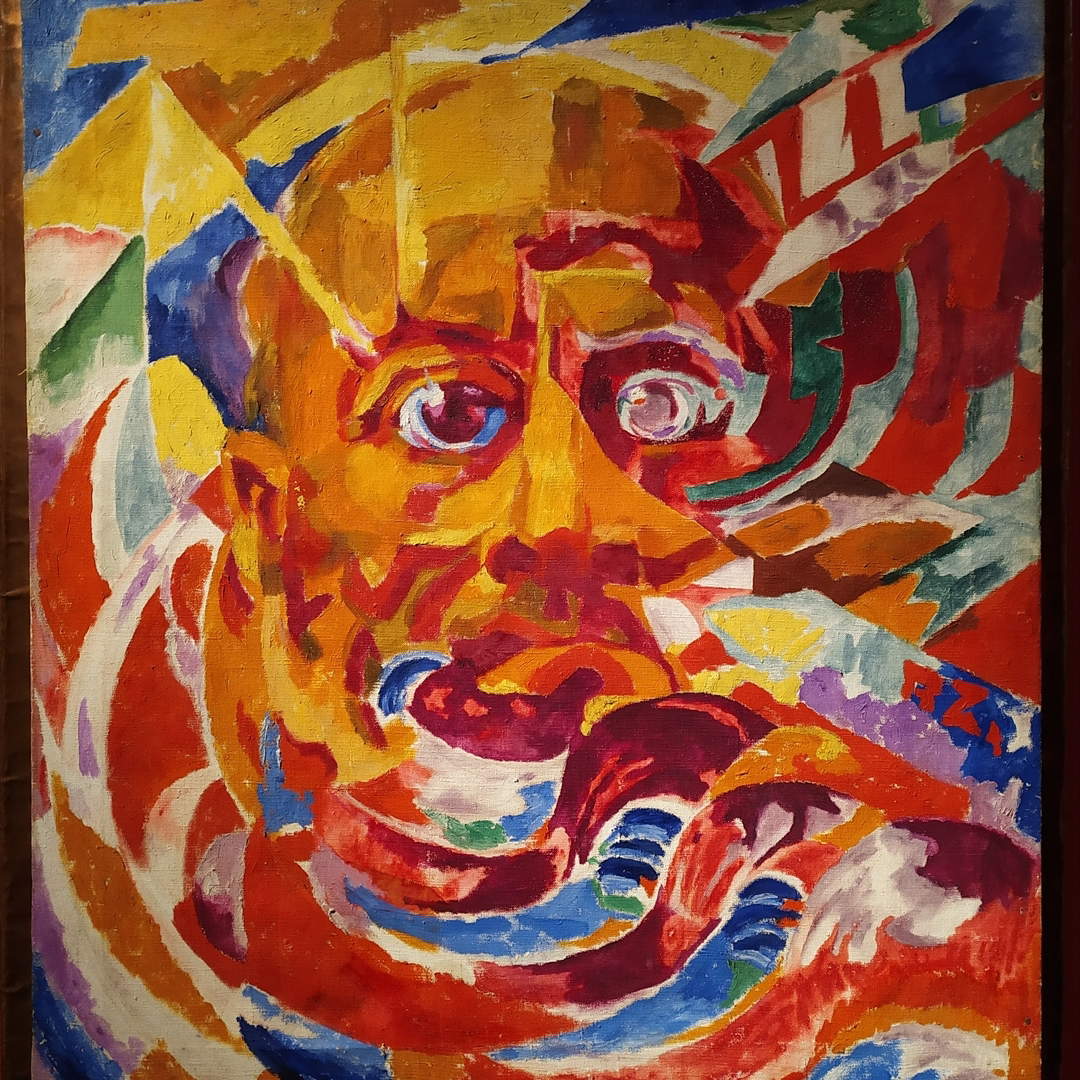

The curator, it was said, wants the substance of the exhibition to emerge not from the record of those present and absent, but rather from the contextualization of what is on display “in a kind of cultural ’sociology’ based above all on the fundamental scientific and technological innovations that accompanied its creation and without which the profoundly and radically revolutionary sense of futurism would completely escape.” Of course, it is difficult to recall one of the many exhibitions on futurism that did not insist on exalting futurism for machines or airplanes, and even the idea of exhibiting automobiles and appliances is not new (the 1986 Palazzo Grassi exhibition had already pioneered this). Equally questionable is the idea of enlisting Guglielmo Marconi in the ranks of futurism, especially where the exhibition attempts to establish a forced parallel between Marinetti’s imagination and the development of wireless telegraphy that earned the scientist the Nobel Prize for physics in 1909, the same year Marinetti published the first futurist manifesto. It is difficult to think of a Futurist Marconi: if anything, wanting to respond with another stretch, it is Futurism that was Marconian. Indeed, one could take a cue from Crispolti and imagine, on the contrary, a Marconi who in fact dampened the electric mysticism, if we want to call it that, of early Futurism, and oriented the research of the Futurists of the 1920s and 1930s by directing it toward a closer relationship close relationship between art and science ("The streetcar appears in the horizon of Boccioni’s La città che sale and invades Carrà’s painting at the same time,“ Crispolti wrote. ”The streets, the signs, the cafes illuminate the night. ’O arms of the Electric / stretched out in every place / to take life, to transform it,’ Folgore will sing in the poem L’elettricità. This unsettling novelty that comes from mystery and moves motors, electricity, is the soul of early futurism. But it becomes ordinary until Marconi’s genius gradually assigns it other fascination and, in the late 1920s, unprecedented perspectives.“). It is also on the basis of Marconi’s research that a futurist like Enrico Prampolini (recalled in the room dedicated to Marconi only for the praise he received from the scientist: he believed he was the only artist who understood his research) elaborated, Filiberto Menna noted as early as the 1960s, ”a modern cosmology based on the notion of relativity and the concept of the fourth dimension, just as the cosmology of Dante’s Commedia was based on medieval astronomy.“ There is no shortage in the exhibition of a fine room on the cosmic idealism of Prampolini and those who shared his intentions (it is among the best-performed in the exhibition), but perhaps the contribution that science and Marconi’s discoveries made to his visionary painting has been underestimated. What remains then to tell the story of the relationship between futurism and technology is the installation by Magister Art, which is supposed to demonstrate to the public the idea that ”artificial intelligence and generative algorithms fit perfectly into Marinetti’s vision of the future, which spoke of the humanization of the machine and the machinization of the human" (so Simongini in the press conference). However, it is not clear how all this should be inferred from a kind of merry-go-round that emits colored lights (supposed to be Boccioni’s States of Mind ) and spreads a Marinetti rant.

Also at the press conference, the international character of futurism was emphasized, a point on which former minister Sangiuliano has insisted a great deal in the past, recalling, whenever the opportunity arose, how futurism was an avant-garde that then spread throughout the world: a strand of investigation, that of international futurisms, which was initiated by Hultén with the 1986 exhibition, but which was then long neglected, and which the Gnam exhibition does not touch upon (the international presences are limited to the albeit important Nude Descending the Stairs no. 1 by Duchamp and a collage by Schwitters, without the visitor being informed as to the reason for their presence), just as the theme of the international relations of the Futurists is not even touched upon, the subject of an exhibition held last year at the Kröller-Müller Museum in Otterlo. It would have been more useful, also for a more in-depth framing of Futurism and to give the public a true idea of its scope, to provide a section that truly gave an account of the international character of the movement, perhaps in place of the’anodyne final chapter devoted to those who would develop, from the 1950s onward, their own research by taking cues from futurism (and even in this case artists who placed themselves almost in the perspective of continuity were mixed with others for whom instead the approach to futurism was episodic).

Without the expectations of the long eve, Il tempo del Futurismo would have been one of the many exhibitions on Futurism that are organized almost annually in Italian museums. And thus essentially an honest, pleasant and well-constructed exhibition, especially in the first rooms, clever in displaying together some Divisionist masterpieces with the early Futurist experiments of Boccioni and companions to show the general public that art history is not a compartmentalized sequence as it is presented to us in the manuals, an exhibition enlivened by many flashes (Balla’s Arc Lamp , Russolo’s Revolt , Balla’s triptych of Affections and again his Child Running on the Balcony, Romani’s Portrait of Dina Galli , the triptych of States ofmoods by Boccioni, Rougena Zatkova’s Marinetti Soleil , Enrico Prampolini’s Futurist puppets that last year kicked off the exhibition on puppets and marionettes at Palazzo Magnani in Reggio Emilia, theIncendio città by Gerardo Dottori), which, however, suffers from the absence of in-depth paneling that would give the public an account of the curator’s choices, also in relation to the presence of works that seem catapulted in the midst of the main works: applies, for example, to Regina’sAcademician , Dudreville’s Florist , Julius Evola’s works, and Sironi’s Dancer . If, on the other hand, we are to consider it one of the most important Italian exhibitions of the last ten years, then Il tempo del Futurismo cannot be considered a milestone, for the reasons mentioned above, and also in relation to the deployment of forces with which the exhibition was constructed.

It should be kept in mind that in order to make The Time of Futurism possible, half the museum was disassembled in order to be able to grant the exhibition the more than four thousand square meters and twenty-six rooms along which Simongini deployed his tour itinerary, which occupies what were sectors three and four of the former Time is out of joint: and, of course, there would have been nothing wrong with that, except that in the other half of the museum there remained just the scraps of Cristiana Collu’s more than questionable installation, the stumps of that postmodern operation that museum visitors have had to endure despite themselves for seven years. Yesterday, the first day of the exhibition’s opening to the public, in addition to Il tempo del Futurismo , only the former Sector 2 of the old installation could be visited. Gnam, in other words, did not bother to provide visitors with an orderly summary of the permanent collection in the halls of the collection: what one encounters is, in practice, the unconventional arrangement, to put it mildly, of the former director, amputated, however, of one of its parts. Under these conditions, a visit to the museum’s permanent collection becomes almost useless. Operation, this yes, truly Marinettian and futurist: visitors interested in the permanent collection will then have to wait for the rappel à l’ordre.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.