Rediscovering John March, cosmopolitan painter. The Livorno exhibition (30 years after the last one).

Giovanni March - The Painter of Light and Atmosphere is the interesting exhibition dedicated to Giovanni March, one of the protagonists of Leghorn and Tuscan painting, open at the Castagneto Banca 1910 representative office in Leghorn until May 27. Almost 30 years after the last exhibition dedicated to Giovanni March, a reflection on the painting of one of the most significant artistic experiences of the 20th century Tuscan scene is finally proposed. March was among the most shining talents of a painting tradition, the Leghorn tradition, which includes personalities of the highest level, including Giovanni Fattori, Mario Puccini, the Tommasi, Leonetto Cappiello, and Oscar Ghiglia, just to name a few of those who had the greatest influence on the artist’s training. Giovanni March knew how to learn stylistic features and artistic solutions from them, later complicated by the comparison with extra-regional and Parisian painting, nevertheless managing to decline a personal and original pictorial research.

March’s is an artistic parabola “on which much is still to be studied, whose relevance cannot be relegated to Livorno alone,” as the curator, art historian and President of the Labronico Group, Michele Pierleoni, puts it. A not dissimilar warning had already been uttered, remaining unfortunately unheeded, back in 1967, when the artist was still alive, by Enzo Carli. The Pisan art historian had in fact feared the risk of seeing March assimilated “to the still numerous ranks of Labronian post-Macchiaioli with a brush as easy as a joke or a savory commentary,” forgetting instead his “vast, well-selected and arduous culture.”

To charge Giovanni March’s art with provincialism, therefore, is a huge mistake, a judgment already refuted by his cosmopolitan childhood. In fact, the painter was born in 1884 in Tunis to Leghorn parents, then moved to Alexandria, Egypt, where his father died, aggravating the economic situation of the artist’s family, which moved to Leghorn in 1908. Here he received his first artistic rudiments from the painter Ludovico Tommasi, thus beginning his activity. In 1917 he was drafted to the front, two years later he was back in Livorno, and in 1920 he was among the founders of the Gruppo Labronico, an artistic association still active today.

The exhibition ordered at Castagneto Banca 1910 is baptized by the fine Bovi cartoon of 1920, a witness to the affection for the Tuscan painting tradition, in a blatant homage to Giovanni Fattori, in which the sharp and nervous sign inferred from the master’s engravings, coexists with suggestions also drawn from the restlessness of Lorenzo Viani and the syntheticism of Mario Puccini. And Puccini’s magisterium is readily apparent in works such as Port of Livorno or Moored Tartanas, albeit mediated by a more earthy palette and wavy painting typical of the Tunisian-born painter. More soothing, on the other hand, are essays such as Casolari con pagliaio from the Pepi Collection and Baracche, where the painting shows a clear compositional architecture declined in large fields composed as chromatic blocks on which the painting is structured, close to the work of Beppe Guzzi, a Ligurian painter who participated for a long time in Livorno’s affairs. While the violet tones that embellish the handkerchiefs of sky are a reflection of the lessons of the first master Lodovico Tommasi, and are found in works such as Figures on the Cliffs, in which, however, a looser and more instinctive painting recalls instead the attitude of Ulvi Liegi.

But that March from the very beginning did not have in his personal pantheon only painters from home is shown by works such as Il quadrigliato, exhibited moreover at the first exhibition of the Labronico Group, and Chitarra e violino, where his fascination for the painting of Cézanne, whom he had known even before his trip to Paris, probably also through works in some Florentine collections, such as that of Gustavo Sforni, appears evident.

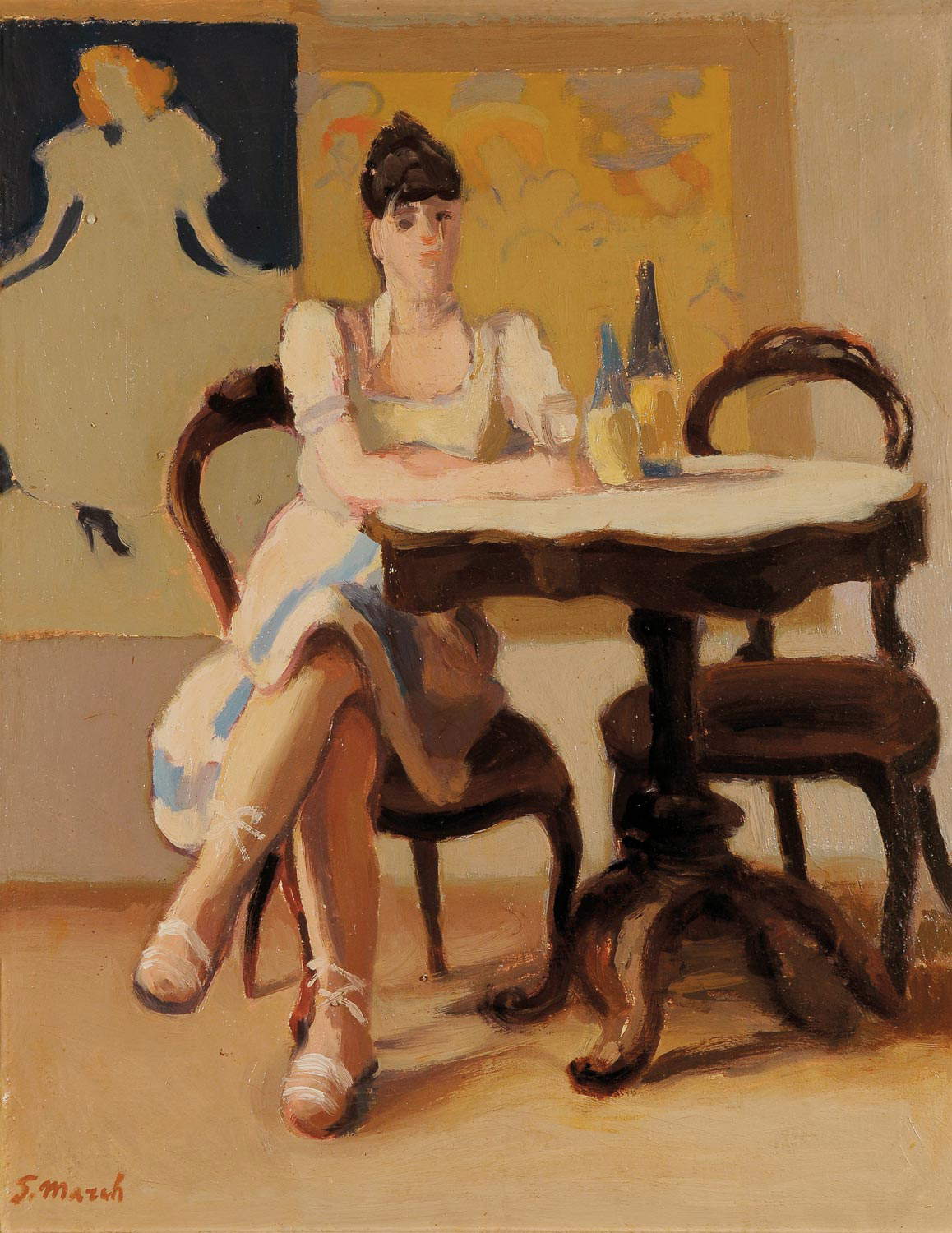

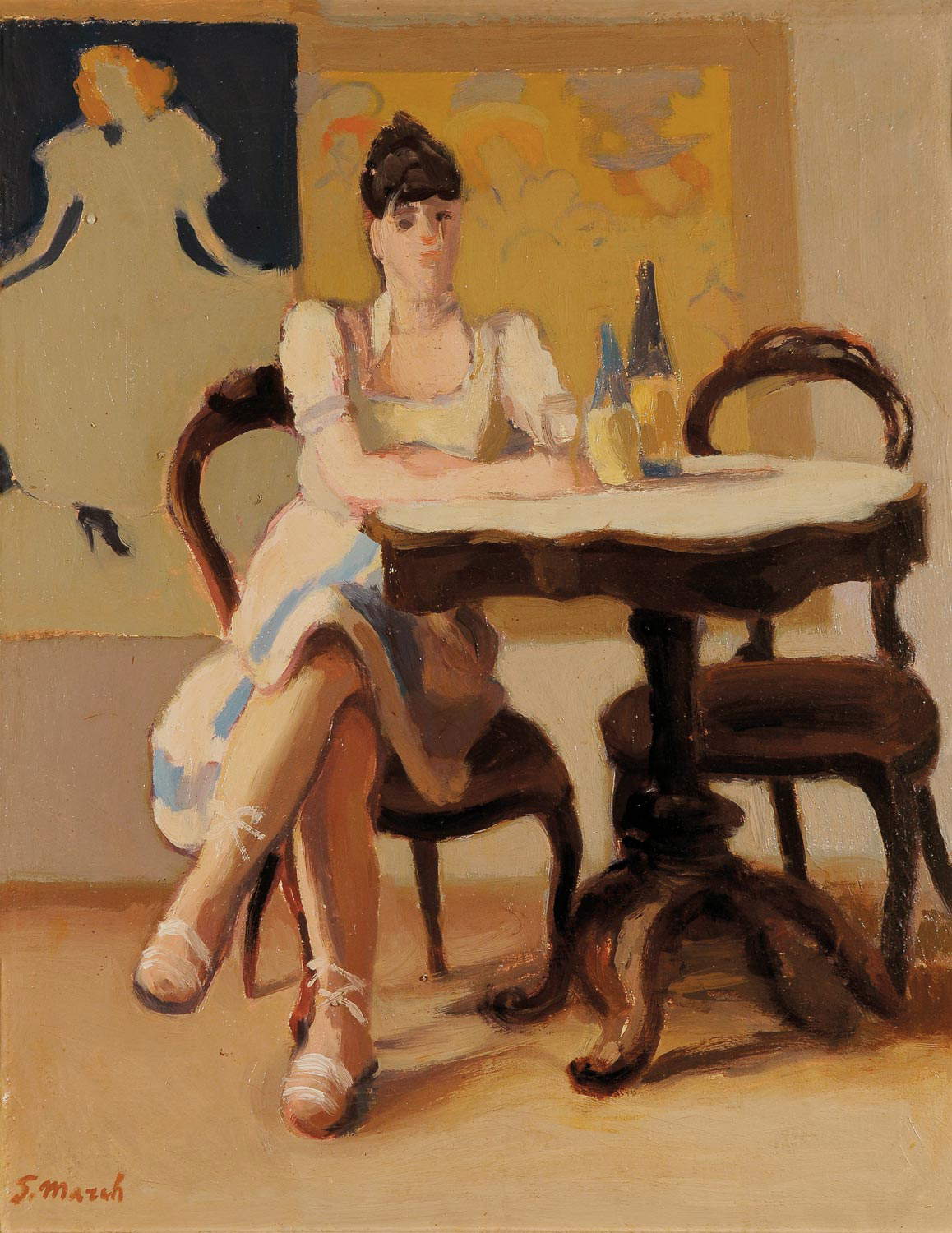

March’s interest in the French masters prompted him to indulge in a two-year sojourn between Nice and Paris that took place between 1928 and 1930. The 1929 canvas Paris - Montmartre shows March’s efforts to adjust the luministic datum from the warm Mediterranean sun to a dimmer, northern light. Also belonging to this season are a number of oil pastels such as Al bar, which betrays March’s interest in the synthetic handwriting and bourgeois sociability scenes of Toulouse-Lautrec. In Paris, the Leghorn artist could rely on comparison with an important fellow citizen, Leonetto Cappiello, who just like Lautrec was laying the foundations of the new advertising graphics; he visited museums and observed the works of contemporary masters such as Monet, Pissarro, Gauguin and Matisse, from the latter he even received compliments. In 1931 he was again in Italy in Rome, where he lived with his family and to which some of the pieces in the exhibition bear witness, such as The Obelisk in Piazza del Popolo, in which the French experience is still alive in the flickering paint and cold zenithal light.

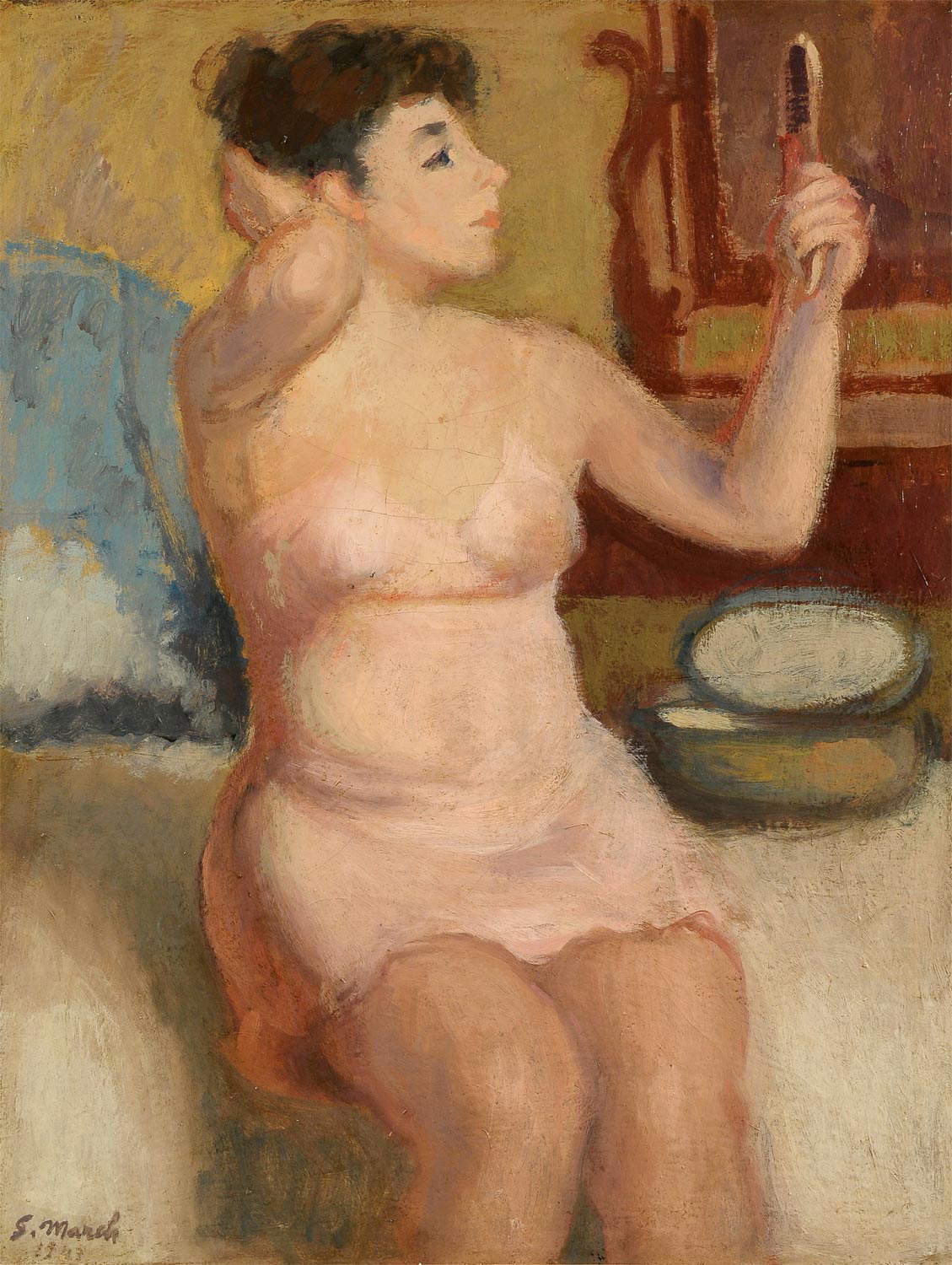

But already in the paintings made upon his return to Leghorn, examples of which are Sulla terrazza dei bagni and Al mare, the chromatics become embellished and almost glazed while the pictorial temperament is pacified. In 1938 the restless painter settled in Florence, and became a member of the Accademia delle Arti e del Disegno, where he met Felice Carena , who together with Amedeo Modigliani constituted a model for dealing with the theme of the nude, whose tactility and warmth of flesh, throbbing with life as in La Cubana or Nudo di spalle. The same warmth and serenity of the nudes is also adapted to the architecture: in Livorno’s Venice, the buildings of the quaint Labron quarter seem to retain a light that is once again Mediterranean. The terrigno chromatic impasto, which we also find in some of the still lifes in the exhibition, is mindful of the interest in Pompeian painting that catalyzes March.

It is thus very difficult to sketch an unambiguous ancestry for our painter, who from time to time takes advantage of different contributions and influences, one need only think of his reinterpretation of Zandomeneghi’s painting in Ragazza che si specchia of 1943 or that of Renoir’s later years in the mellow rendering of Pastorella. While in Self-Portrait at the Café March effigies himself inside an imaginary bar with bright colors, taken from an affiche by Leonetto Cappiello.

But March is also receptive to the poetics of the Italian twentieth century, as in Molo e cabina Antignano of 1949 or Cecina of 1964, where he entrusts the scanning of planes to tonal values and a complex inlay of color backgrounds organized in an almost symphonic modulation, cloaking the works in rarefied, silent and strongly emotional atmospheres.

In the 1950s he was again in Paris, while in 1970 in Moscow and Leningrad, in 1971 in Odessa and the following year between London and Durham. Evidence these of a spirit that never paid off, even late in life, as confirmed by the graceful woodcut The Bathers, made the year before he died, from the joyful, carefree rhythm of Matisse, and in which dazzling colors and the organization of the figurative datum seem poised between a cloisonné stained-glass window and the fresh, satisfying rendering of pop art.

The Livorno exhibition, through some forty works held in private collections or belonging to the Livorno Foundation, has the great merit of giving a clear reading of March’s artistic journey, or rather adventure, because of that ability of his to constantly abandon the sure path mapped out with effort, toward ever new and unpredictable paths. The Leghorn master succeeds in making these varied experiences always homogeneous by tracing them back to his own culture, the Mediterranean one dripping with “light and classical aesthetics,” as the curator states.

In short, the exhibition does not have the systematicity that a large and ponderous retrospective could orchestrate by highlighting all the directions and interests that this lion-like figure possessed, but on the other hand through a very calibrated itinerary that makes use of paintings of excellent quality, it has the great merit of shedding light on an artistic experience of great interest, placing a first but fundamental step for the rediscovery of this incredible personality.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.