by Federico Giannini (Instagram: @federicogiannini1), published on 25/10/2017

Categories: Exhibition reviews

/ Disclaimer

Review of the exhibition 'Plinio Nomellini. From Divisionism to Symbolism Toward the Freedom of Color' in Seravezza, Palazzo Mediceo, from July 14 to November 5, 2017.

“The charge I have had on behalf of the Academy is to pray to the Tribunal that it may restore to art one of the finest intelligences, of the most fruitful workers, a young man who is destined for a great future and who, besides doing honor to himself, will do so to his country.” Thus began the speech that Telemaco Signorini gave before the Court of Genoa in 1894 in defense of his young friend Plinio Nomellini (Livorno, 1866 - Florence, 1943), accused of subversion along with a group of anarchists active in the Ligurian capital. It is difficult to precisely frame and thoroughly understand an artist like Plinio Nomellini without having knowledge of this experience, which cost him several months of incarceration. The reason for such a difficulty is given to us by Signorini himself in the continuation of his vivid and impassioned testimony: “Nomellini, artist as he is, needed high aspirations, high ideals, and just as in art he was a rebel against ours, and sought in another method the satisfaction he was looking for, so he also felt in life the need to get out of the ordinary, and get to know those whom today’s society called utopians.”

Indeed, the whole life of the great Tuscan artist was marked by a perennial tension toward the new, a constant desire to experiment and confront, and an inability to remain anchored to a tradition, a pattern, or an acquired experience. In painting, he debuted under the sign of Giovanni Fattori and macchia painting, was then a pointillist capable of experiments never attempted by others before him, and finally veered toward an intimate and poetic symbolist painting. All of this, net of that painting dense with rhetoric that marked the last phases of his career: because even on the level of political beliefs, Nomellini was often led to revise his convictions, albeit within a path that, seen from the inside and judged by looking at the man and his experiences, can also be considered decidedly coherent. Thus, from militant anarchist close to the Genoese workers’ circles and subversive groups, after the trial of 1894, from which he was acquitted, he settled on more moderate positions but still libertarian in nature, and then allowed himself to be influenced by the decadent poetry of Pascoli and D’Annunzio, to whom he drew close when he moved to Versilia: the disappointment of the failed political struggles led the artist to believe that emancipation could only come from the recovery of a relationship with nature endowed with regenerative force and capable of elevating man by allowing him to overcome the patterns imposed by the social order. Hence, Nomellini’s adhesion to interventionist instances, and finally his convinced adhesion to fascism, which decreed, at least for thirty years, a sort of damnatio memoriae towards him. As a single and constant leitmotif, painting: a true, indispensable means for the social and cultural redemption of humanity.

The entire artistic and human parabola of Plinio Nomellini is summarized in an exhibition, entitled Plinio Nomellini. From Divisionism to Symbolism Toward the Freedom of Color, which is being held in the rooms of the Palazzo Mediceo in Seravezza, in the very Versilia where the painter lived for more than a decade, frequenting its cultural circles, breathing its humid and salty air, immersing himself in the dazzling light of that “cerulean and tawny summer” that inspired D’Annunzio’s immortal verses and Nomellini’s paintings “where forms and colors are shaped by the spirit” in order to “animate nature, capture its intimate mutability and fundamentals” (so Silvio Balloni in his catalog essay): a yearning to which many Symbolist painters aspired, but which Nomellini pursued with a lyrical and panic sensibility that probably had no equal. The Seravezza exhibition, curated by Nadia Marchioni, succeeds in making us participants in the poetic inspiration of Nomellini’s work, dedicating ample space to his Versilia production, and leading us toward these results with a path endowed with great philological rigor, reconstructed on a chronological basis and with precise comparisons, strengthened by a precise and effective didactic apparatus, so that each room represents a step deeper into Nomellini’s art and, by virtue of the incessant mutability of his painting, an ever new surprise for those who have yet to make his acquaintance.

|

| The Palazzo Mediceo in Seravezza for the exhibition on Plinio Nomellini |

|

| The first room of the exhibition |

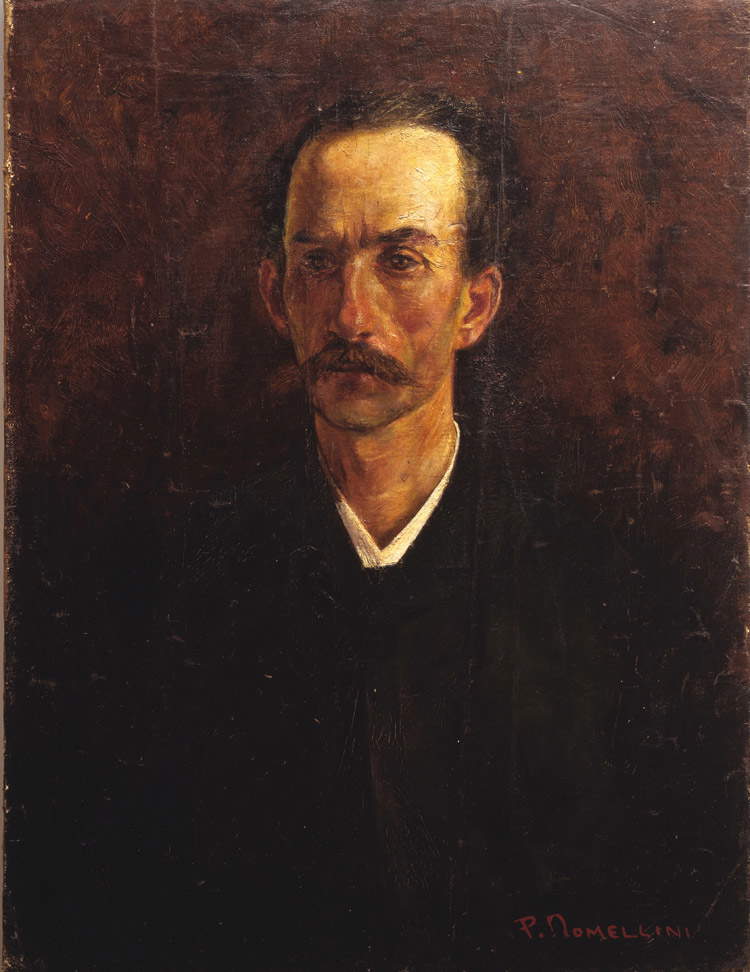

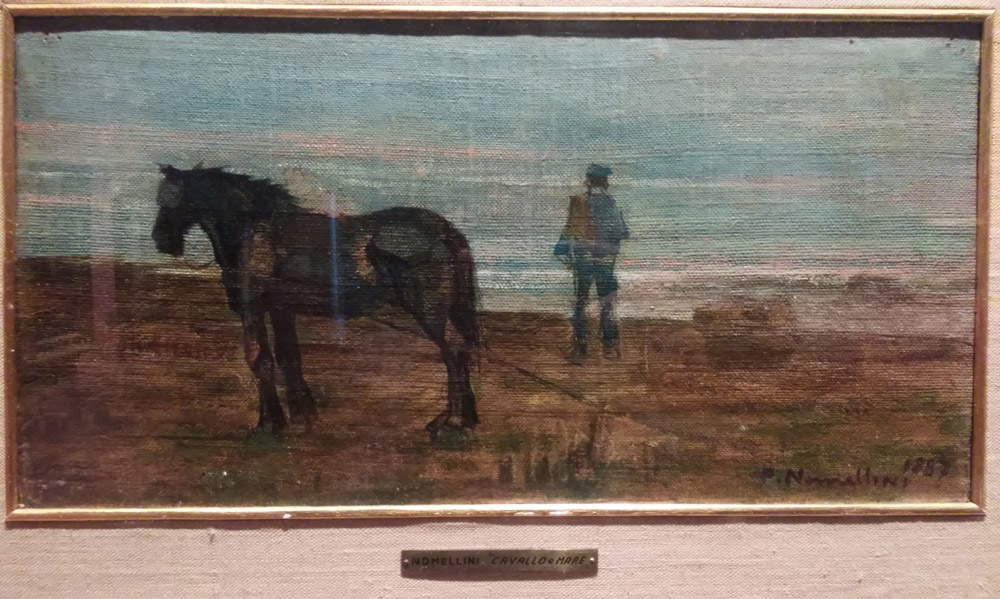

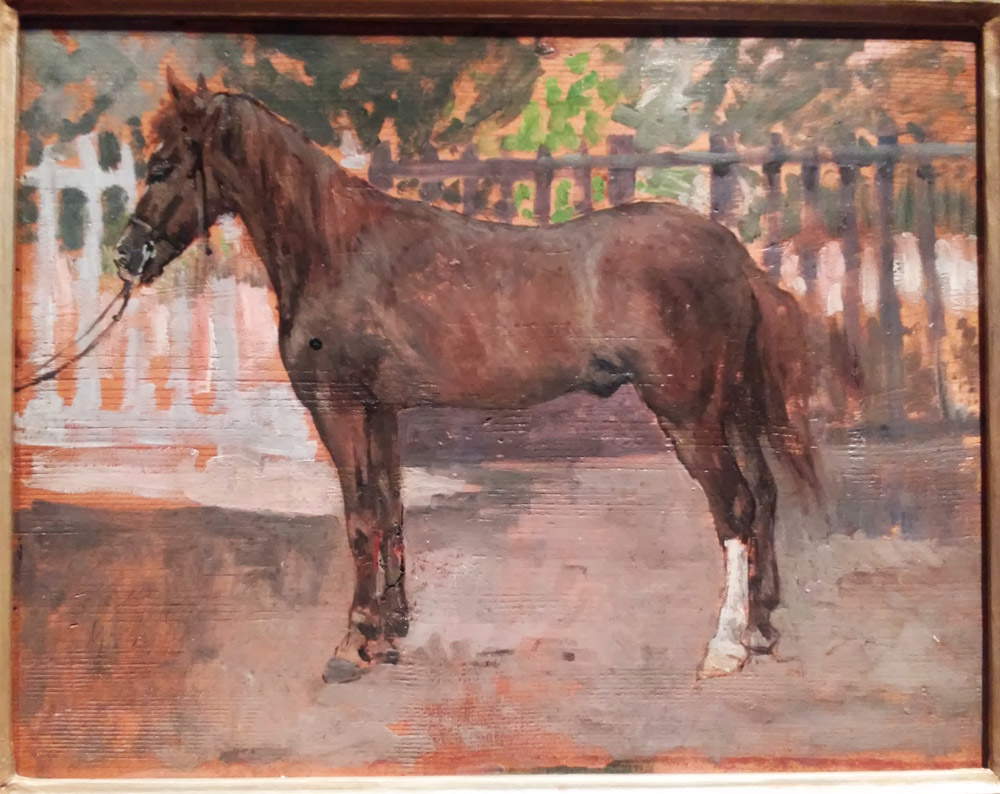

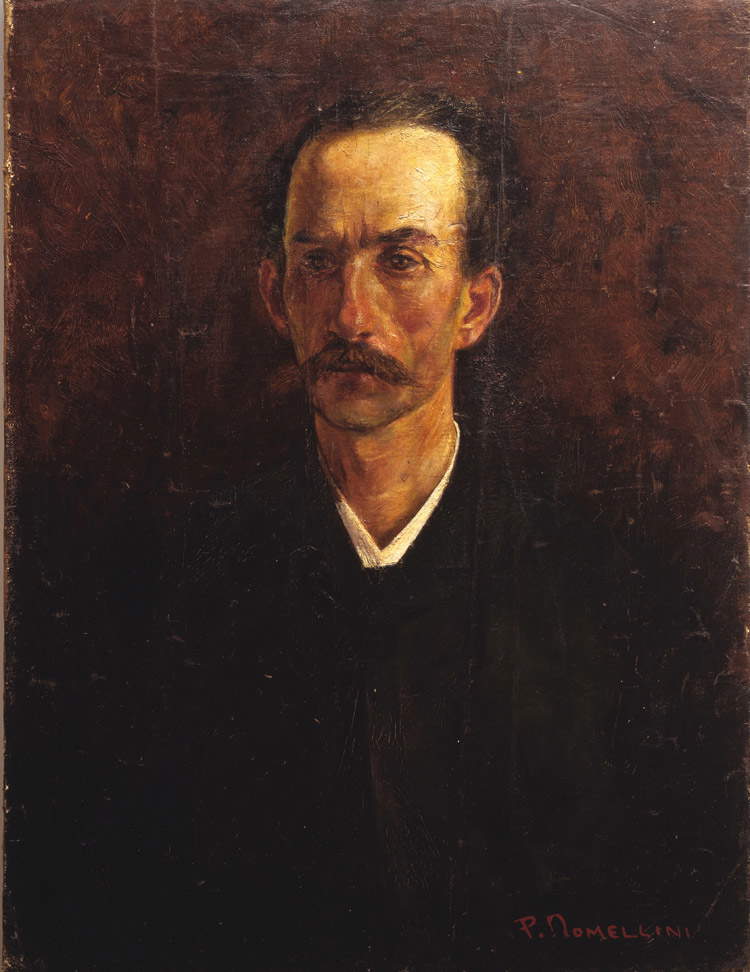

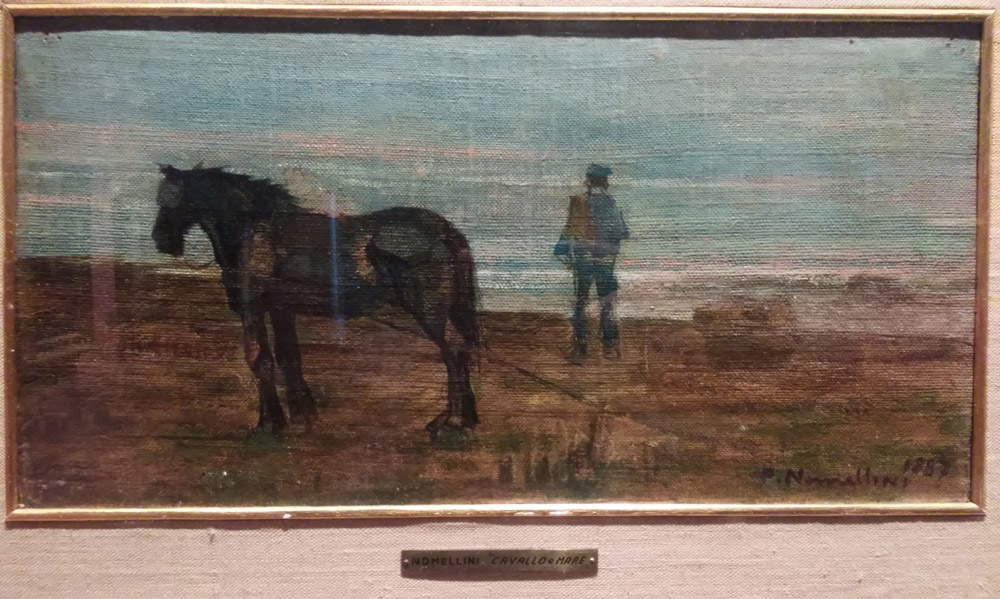

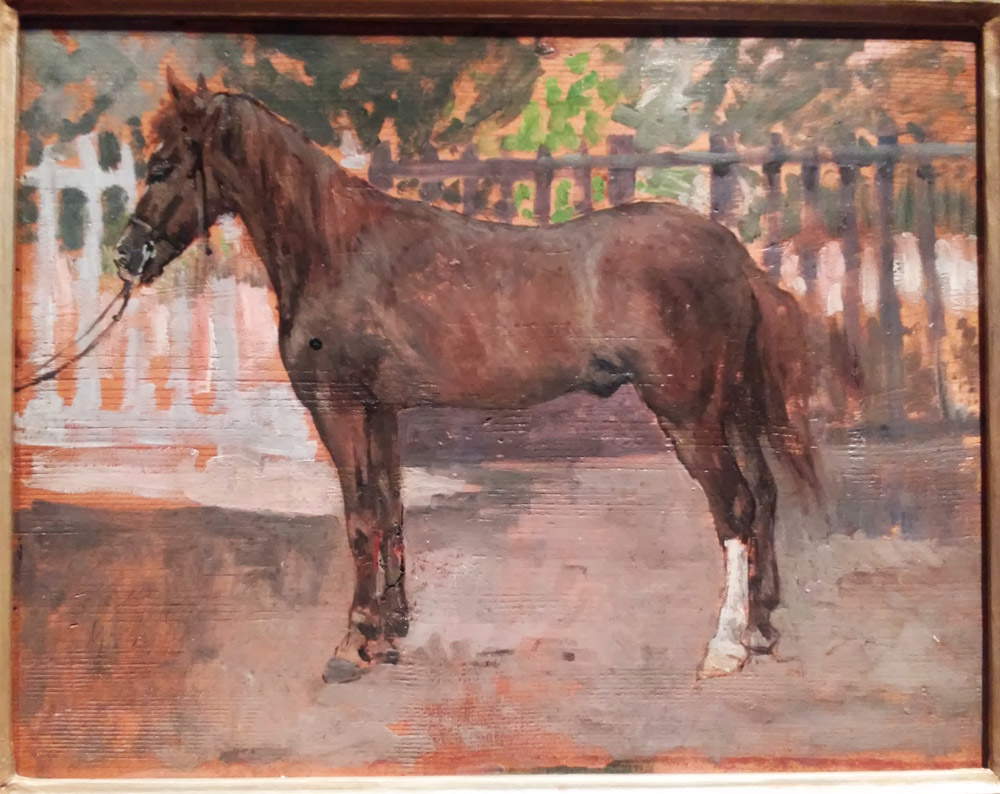

The opening of the exhibition introduces us to a Nomellini barely nineteen years old, but already confident of his own means and talent. An intense portrait of his father Coriolano, painted around 1885, fixes the characteristics of this phase: the artist, after having shown an early inclination toward drawing and, consequently, after having attended the art schools of his city, moved to the Academy of Florence where he had as a teacher his fellow citizen Giovanni Fattori (Livorno, 1825 - Florence, 1908), who directed him toward a Macchiaioli-style painting, sharp, clean, endowed with a solid and traditional graphic structure. Thus the comparison between pupil and master arrives in a timely manner, with one of Fattori’s dearest themes, that of the horse (an animal that, wrote Raffaele Monti in his monograph on the artist, “for Fattori is a formal archetype capable of arousing in his sensibility the invention of continuous and highly original forms”): lonely and behind a fence that of the master, immersed in an evocative landscape at sunset that of the pupil, with the additional difference that his animal figures in the company of a character observing a sea veiled in reddish streaks, already presaging suggestive future solutions. Both animals are marked by a decisive, Tuscan outline: accurate drawing is a constant specification of all Nomellini’s early paintings. Other good examples gathered in the next room, which is intended to give an account of the cultural climate of Florence at the time, are some portraits of ladies, also modeled on the groove of Giovanni Fattori’s painting (from which he also derives hisattention to the real), and a frowning Ciociara of 1888, which, even in its dimension of an academic exercise on a model, already denotes Nomellini’s closeness to the lower classes, the workers, the humble, as well as to painting as a vehicle of political and social instances: his Ciociara, dressed in the typical dress of her lands, has hands tried by the work of the fields, but the pride that shines through her gaze does not prevent her from renouncing her femininity and adorning herself with a showy dangling earring, a small silver ring and a poor necklace.

The climate of that time, it was said, is evoked in the room in which the so-called “Bohème del Volturno” is presented: Nomellini and several young artists (Giuseppe Pellizza da Volpedo, Ermenegildo Bois, Ruggero Panerai, Giorgio Kienerk, Angelo Torchi et al: their works are featured in the exhibition) used to gather in a large room of the trattoria Volturno, an establishment on Via san Gallo in Florence, around the more experienced Silvestro Lega (present in Seravezza with two paintings) and Telemaco Signorini, with whom they established a relationship of mutual and fruitful friendship, nevertheless frowned upon by Giovanni Fattori, who considered such frequentations deleterious to the careers of his students and who wrote fiery letters about them, without, however, ever losing his esteem for that group of boys whom, in fact, he had seen grow up in the studies of the Academy. Studies from which we can imagine taken as much Plinio Nomellini as Giuseppe Pellizza da Volpedo (Volpedo, 1868 - 1907): an essay in the catalog, signed by Aurora Scotti Tonsini, is dedicated to their relationship, as well as a comparison in the exhibition with two paintings executed on the same model( Pellizza da Volpedo’sWaiting and a further Ciociara by Nomellini), two exercises resulting from the same posing session and in Seravezza exhibited next to each other. Both paintings, writes Scotti Tonsini, that demonstrate “the ability to confidently place the figure in space and, above all, to give it strength and dignity,” albeit with differences: “more sensitive to constructing the figure’s framework by focusing on a solidity of form and with a more defined outline mark was Pellizza’s painting, looser in construction and, above all, lively in the use of color substantiated by light that of Nomellini.”

|

| Plinio Nomellini, The Father Coriolanus (c. 1885; oil on canvas, 62 x 46.6 cm; Private collection) |

|

| Plinio Nomellini, Horse on the Sea (1887; oil on canvas applied to cardboard, 18 x 34.8 cm; Private collection, courtesy Galleria Athena, Livorno) |

|

| Giovanni Fattori, Study of a Horse (ca. 1885; oil on panel, 25 x 33 cm; Livorno, Museo Civico Giovanni Fattori) |

|

| Comparison between Plinio Nomellini’s horse (left) and Giovanni Fattori’s horse (right) |

|

| Plinio Nomellini, Ciociara (1888; oil on canvas, 66 x 62.5 cm; Private collection, courtesy Society of Fine Arts, Viareggio) |

|

| Left: Giuseppe Pellizza da Volpedo, The Waiting (1888; oil on canvas, 110 x 57 cm; Private collection, courtesy Studio d’Arte Nicoletta Colombo, Milan). Right: Plinio Nomellini, Ciociara (1888; oil on canvas, 114.5 x 47 cm; Private collection) |

This lively use of color went, however, more and more away from Fattori’s lesson: one of Volturno’s young men, Alfredo Müller (Livorno, 1869 - Paris, 1939) had stayed for some time in Paris, updating himself on the results of the Impressionists’ research, and then returned to Florence and began to communicate to his friends, with transport and enthusiasm, the innovations he had learned in France. Not that in Italy, at the time, Impressionist painting was an unknown object: in Florence the first Impressionist works, two paintings by Pissarro, impressionismo-francese-prima-volta-in-italia-1878.php' target='_blank'>had arrived in 1878 through the interest of the art critic and collector Diego Martelli (Florence, 1839 - 1896), without, however, meeting with favor in the environment. Far from it: almost all the Macchiaioli remained firmly in their positions. Foremost among them was Fattori, who in that fateful 1878 looked askance at the paintings arriving from Paris, and was for that reason reprimanded by Martelli, with whom relations cooled. The only ones open to novelty were Lega and Signorini: not by chance the two artists to whom, thirteen years later, Fattori made the accusation of wanting to drag “those good and dear young people” into the “abyss” of painting beyond the Alps. Müller’s return, however, marked an irremediable rift between the “old men” attached to the Academy and the “young men” gathered around Martelli, Lega and Signorini. And among the latter was, of course, Plinio Nomellini. His first Divisionist experiments date back to the late 1980s: a significant transitional work, the Ricordo di Genova (or On the Beach), is on display. It is a scene set on a Ligurian beach on a bad weather day, with large threatening clouds laden with rain: a mother is playing with a child, two men are chatting on the seashore, others are leaning against a boat. Also exhibited in Seravezza is the preparatory drawing, which shows how Nomellini has not yet abandoned the master: the beach, however, with those typically Divisionist touches of color already suggests how the artist feels the urge to free himself from the master. Or he has already freed himself from it: the juxtaposed speckles that give the sense of momentary impression could be a later intervention, made on a painting conducted with more traditional techniques (a dating to 1889-1891 has therefore been proposed).

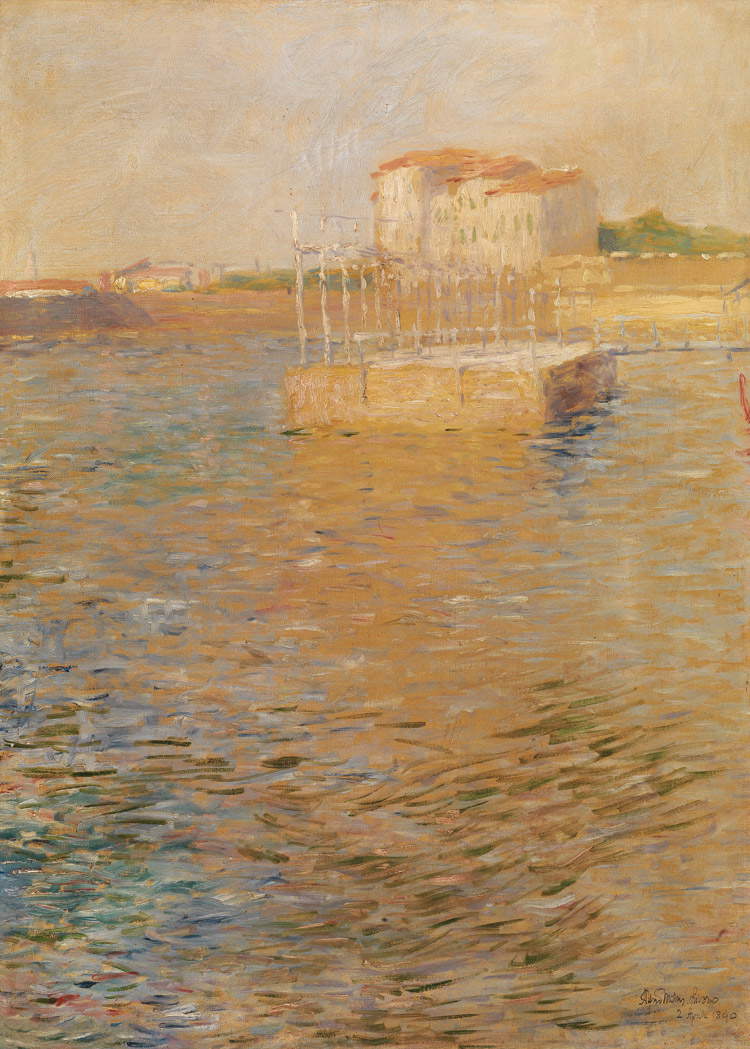

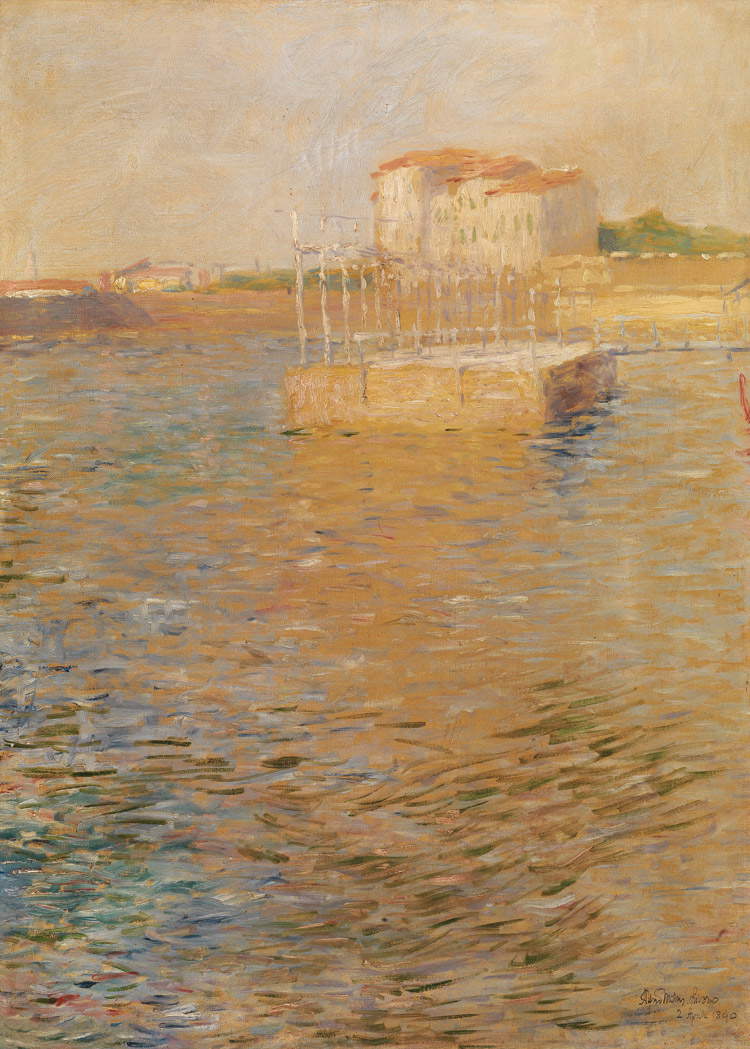

It is doubtful that, in his approach to pointillism, Nomellini looked to Müller (in the exhibition present with his Bagni Pancaldi in Livorno), who had been fascinated by Monet but had not gone further: it is likely that the go-between was someone else, but at the moment we have no certain data on which to base ourselves. What is certain is that the researches of the French pointillists must have fascinated him not a little, to the point that his first totally pointillist work dates back to 1891, a daring experiment(The Gulf of Genoa) which, according to Nadia Marchioni, takes the form of a “betrayal” of the master’s graphic teaching: because here drawing disappears, because the forms are built up only by that “very dense weave of small brush touches” that acquire a luminosity never previously achieved. It is the seal of a generational clash, as well as the final farewell to the almost seventy-year-old master, who in a moving letter written on March 12, 1891, informed his barely twenty-five-year-old pupil that he did not approve of his new research, but also let him know that his esteem for him remained unchanged: “I thought it my duty to warn you and the others that you were following a path already traced 10 or 12 years ago, and that the very appreciable youthful fire has made you see that the History of Art would record you as martyrs, and innovators, while the History of Art will record you as the most humble servants of Pisaro, Manet, etc. and ultimately of Mr. Muller [...]. You alone by justice I find you original as I said in the workers [...]. This is history and here I cease to say to myself your friend always, master never again! For I am with the old men, and I would no longer know what to teach you-you will tell good Leghorn friends when you have occasion to write them-I shake your hand and am your affectionate friend. G. Fattori.”

|

| Alfredo Müller, I bagni Pancaldi a Livorno (1890; oil on canvas, 75 x 53.5 cm; Private collection, courtesy 800/900 Artstudio, Livorno-Lucca) |

|

| Plinio Nomellini, Ricordo di Genova o Sulla spiaggia (1889-1891; mixed media on paper, 41 x 58 cm; Goldoni Gallery, Livorno) |

|

| Ricordodi Genova o Sulla spiaggia, detail |

|

| Comparison between Ricordo di Genova o Sulla spiaggia and his drawing |

|

| Plinio Nomellini, Il golfo di Genova o Marina ligure (1891; oil on canvas, 58.5 x 95.8 cm; Tortona, Pinacoteca “Il Divisionismo” - Fondazione CR Tortona) |

Having dissolved his ties with Fattori, Nomellini was able to find his own way, and pointillism became the most suitable medium for his social painting, to which an additional room is devoted: the Diana of Labor of 1893, perhaps his best-known work of this period, which depicts a crowd of workers waiting, early in the morning (Diana-style, in fact) for the gates of a factory to open, which spreads its grayness over the gloomy figures of the workers and darkens the man in the foreground, who wanders as if lost, followed by an already equally alienated child.

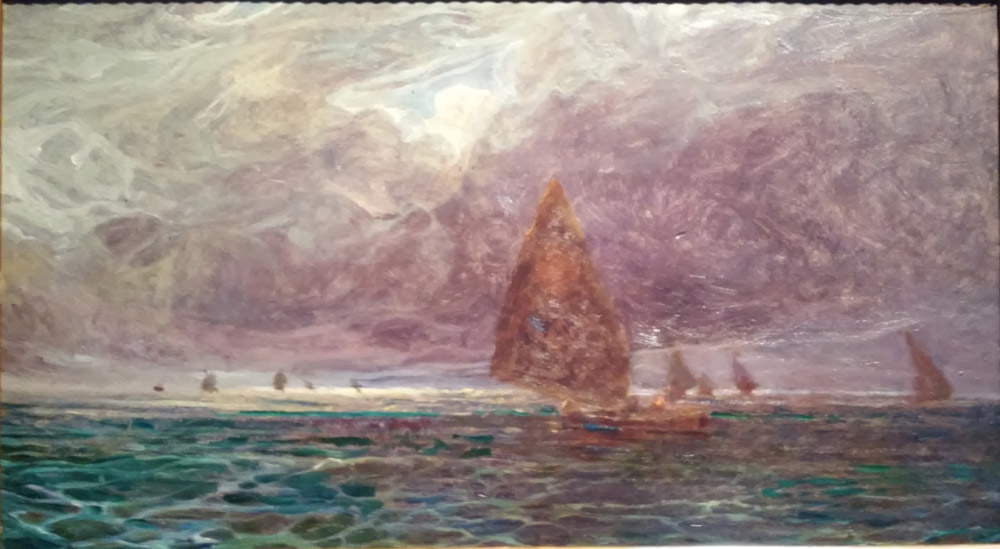

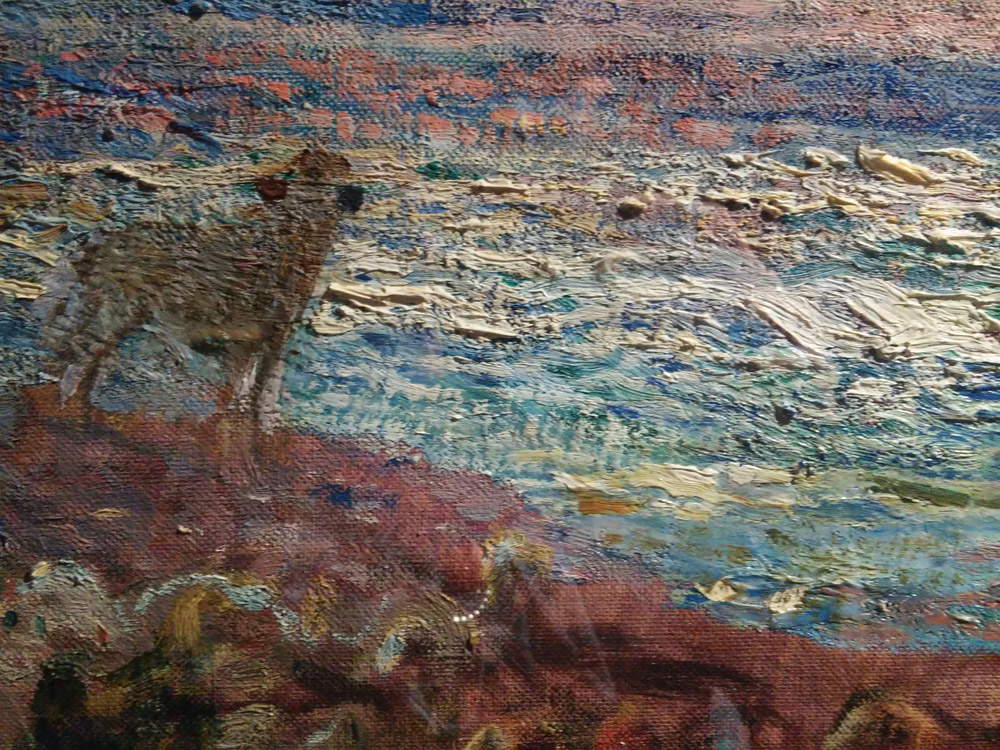

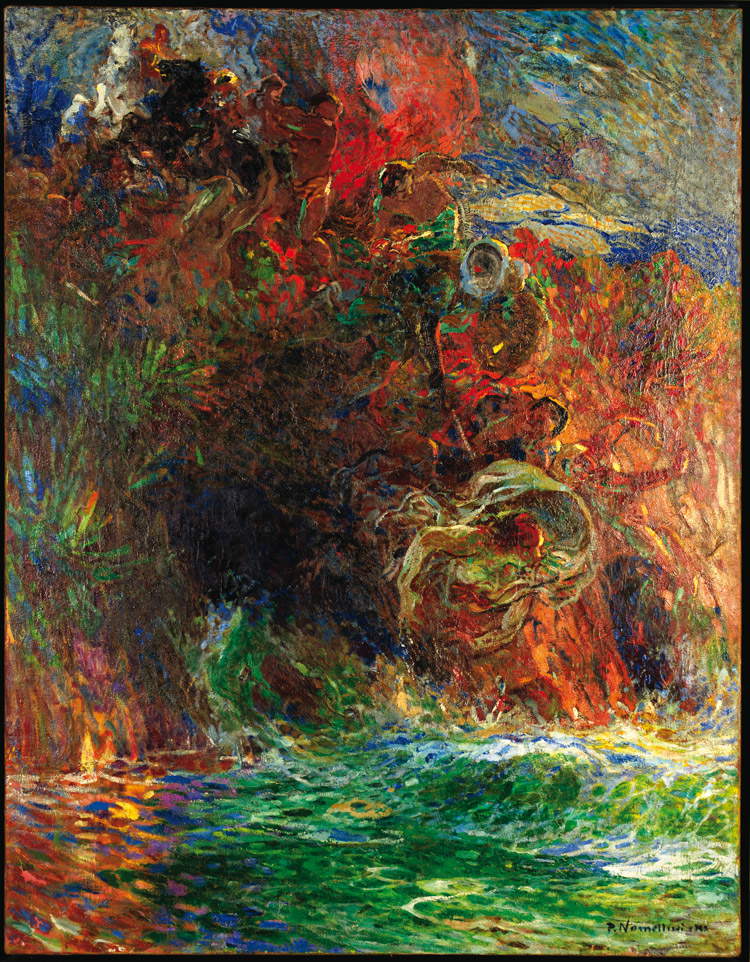

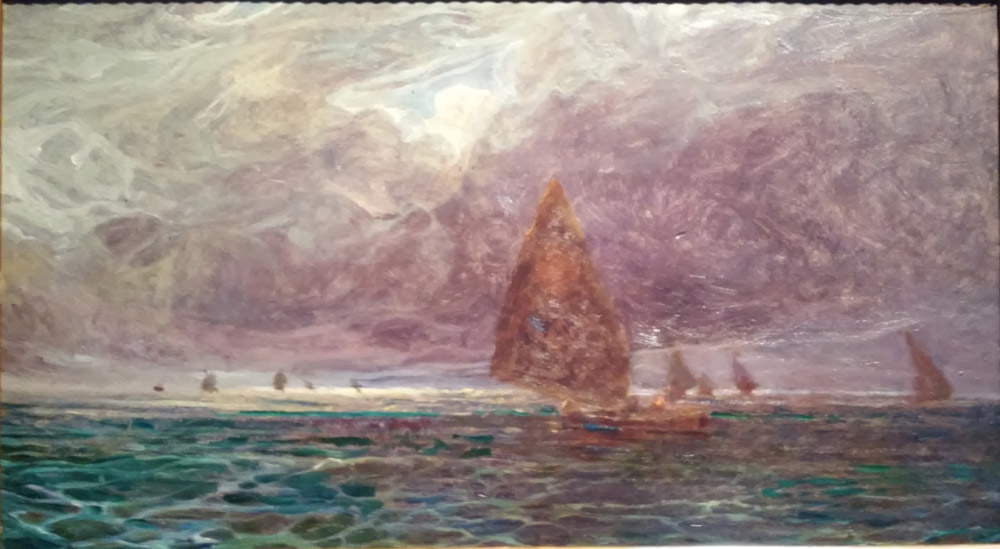

Of the disappointments that social struggles caused Plinio Nomellini, we have already mentioned: the most natural refuge was therefore literature, to which he approached when he began composing illustrations for La Riviera Ligure, the singular publishing project that began as an advertising bulletin for the Sasso oil mill and later became one of the most up-to-date literary magazines in Italy. These experiences, which brought Nomellini closer to the poetry of Giovanni Pascoli and Gabriele D’Annunzio, helped give his paintings that dreamlike grace and timeless dimension that characterizes works executed at the dawn of the 20th century. The evocative Marina of 1900, with the rough sea on which the waves, once broken, form plots of white circles (typical, from here on, of most of the artist’s sea views), is an image that, writes Silvio Balloni, communicates a “sense of mystical stillness” and above all sanctions “the artist’s fusion with nature,” which would become even more total in later paintings: nature, for Nomellini, is a living organism, endowed with a vitality of its own, which the artist must make his own by binding himself to its disruptive force and recognizing himself in every shrub, in the rustling of the foliage, in the wind that stirs the sea, in the drops of rain, in the fragrances of flowers. Plinio Nomellini is perhaps the artist who more than any other gave a painted image to D’Annunzio’s panism. As an example, the visitor, losing himself in the pine forest at the center of the Pineta, cannot help but think back to the poet’s lines, “Listen. It rains / from the scattered clouds. / It rains on the tamarisks / brackish and burnt, / it rains on the pines / flaky and bristling, / it rains on the myrtles / divine, / on the gorse fulgent / of flowers welcomed, / on the junipers thick / of cuddling aulent, / it rains on our faces / sylvan, / it rains on our / naked hands, / on our / leggier garments, / on the fresh thoughts / that the soul unfolds / novella, / on the beautiful fable / that yesterday / deluded you, that today deludes me, / o Hermione.”

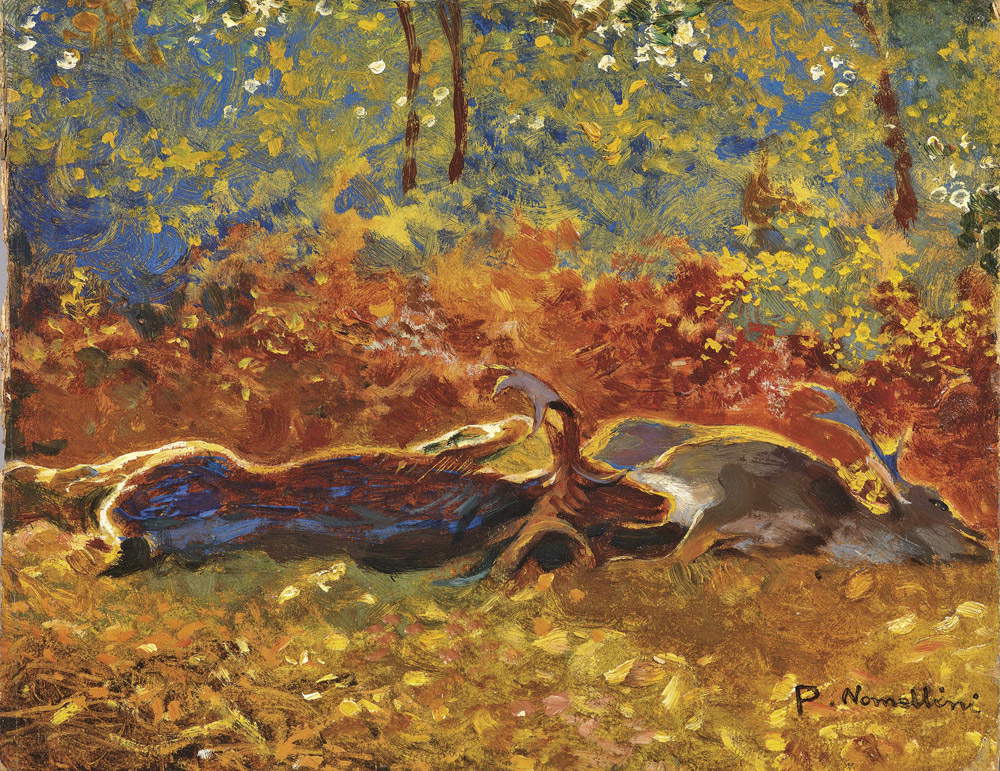

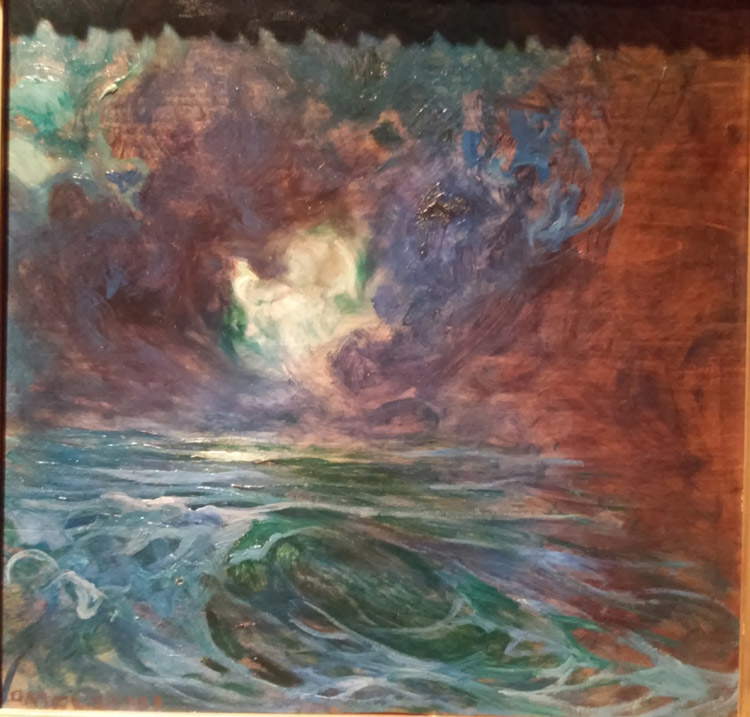

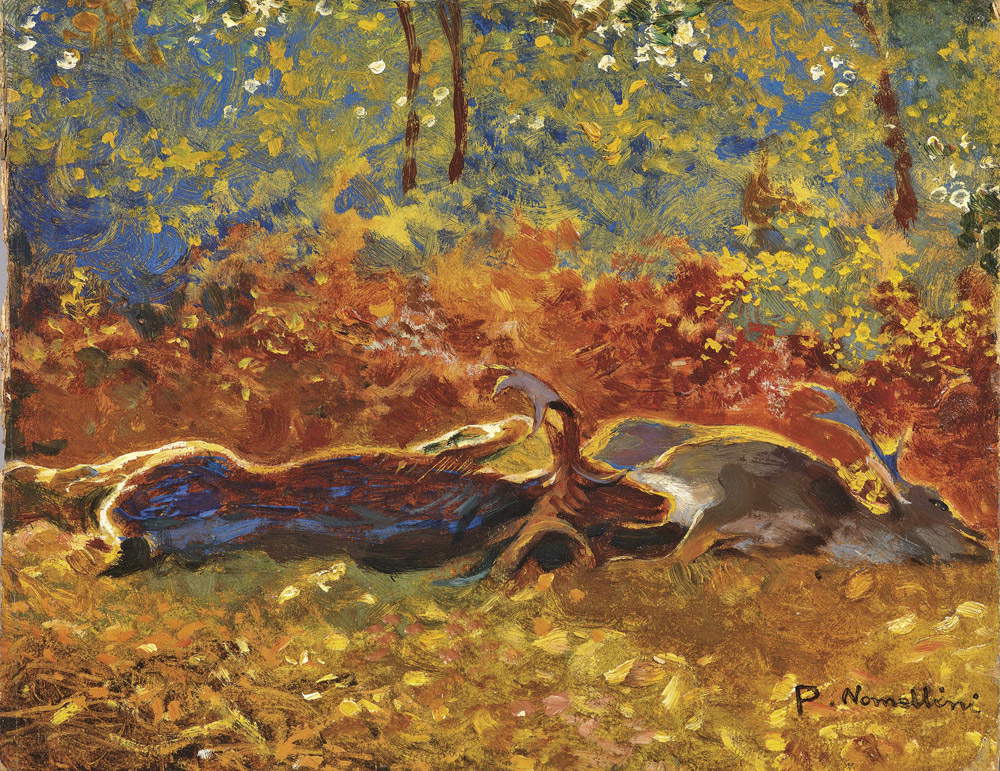

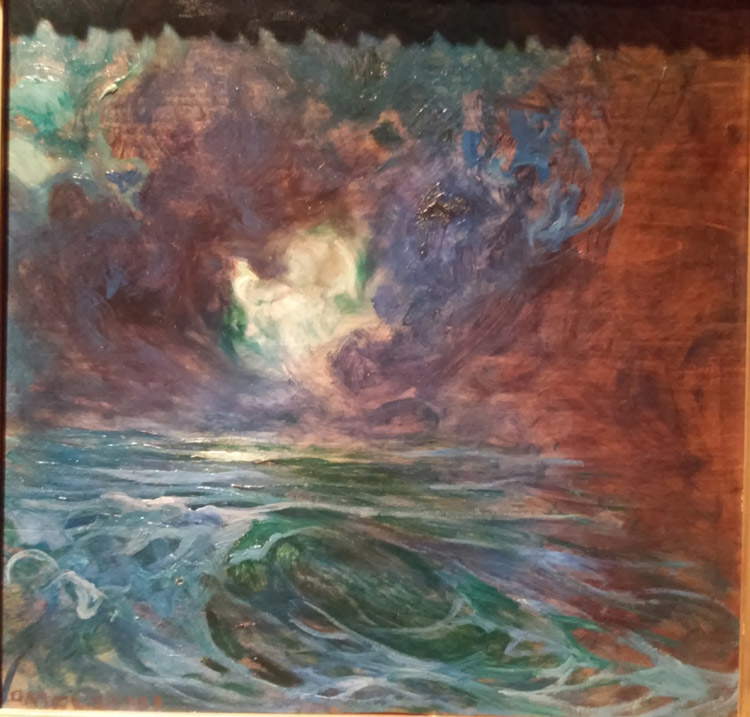

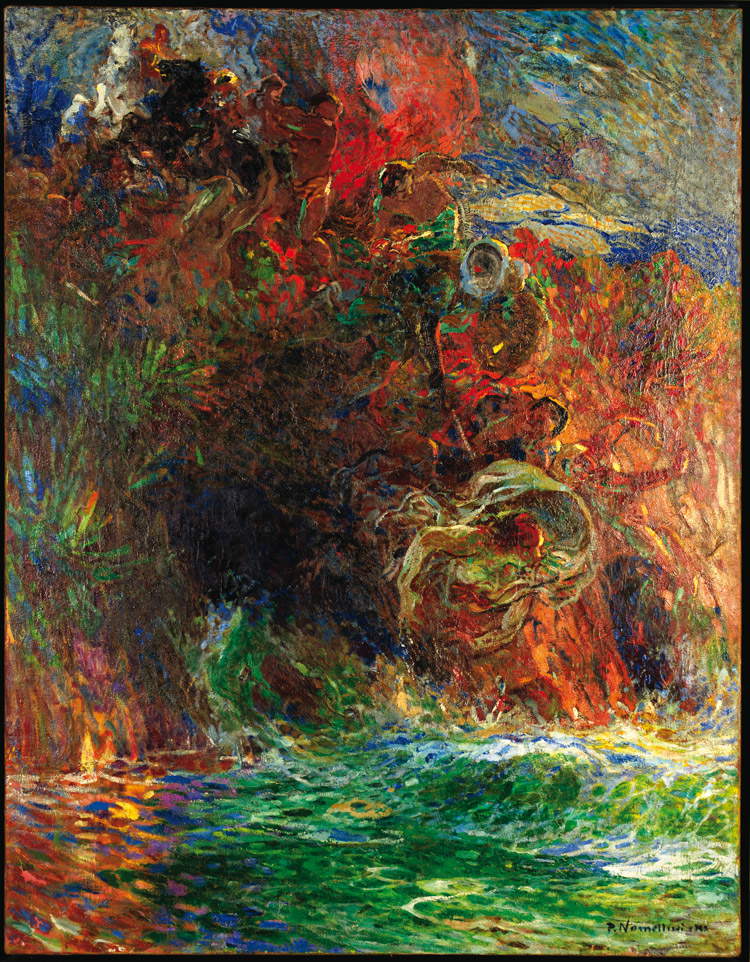

D’Annunzio’s suggestions continue: the Dead Deer recalls the lyric Death of the Deer, and the Nocturne, with the moonlight that illuminates with silver reflections the lapping of the waves of an agitated sea beneath a cliff, brings us back to the roar of water evoked by the Vate in The Wave. The marvelous Red Nymph, an ethereal and delicate creature of the coastal woods immersed in a fiery sky, an image perhaps more than others representative of the new pagan myths celebrated by Nomellini’s brush, almost seems to utter the words of Versilia: “Fear not, O man of glaucous eyes / glaucous! Erompo from the bark / fragile I woodland nymph / Versilia, for you to touch me. [...] / I spied you from my shaft / flaky; but you did not hear, / O man, beat my living / eyelashes by your adorned neck. / Sometimes the flake of the pine tree / is like a rough eyelid / that at once closes, / in shadow, to a divine gaze.” Panic symbolism is then transformed, as a consequence, into heroic painting (heroic, after all, is man regenerated by his symbiosis with nature) such as that of Gli insorti, a work in which a nature cloaked in political meanings (the scene takes place at dawn with a sun that begins to brighten the protagonists) serves as a backdrop for the “insurgents” who give the painting its title: none other than Pisacane’s patriots, the embodiment of the post-Risorgimento myths in vogue at the time. The work was exhibited, with mixed critical fortune, at the 1907 Venice Biennale, in a room called L’arte del sogno and conceived by Nomellini himself and Galileo Chini (whose Icaro we see on display on that occasion as well): the Seravezza exhibition seeks to recreate that environment by presenting to the public some of the works that the Leghorn artist brought to the 1907 Biennale.

|

| Plinio Nomellini, La diana del lavoro (1893; oil on canvas, 60 x 120 cm; Private collection) |

|

| Plinio Nomellini, Marina (ca. 1900; oil on cardboard, 34 x 56 cm; Goldoni Gallery, Leghorn) |

|

| Marina, detail |

|

| Plinio Nomellini, Pineta (c. 1900; oil on canvas, 85 x 85 cm; Private collection) |

|

| Plinio Nomellini, The Dead Deer (c. 1904; oil on cardboard, 27 x 34 cm; Florence, Private Collection) |

|

| Plinio Nomellini, Nocturne (1905-1910; oil on panel, 37.5 x 37 cm; Private collection, courtesy Società di Belle Arti, Viareggio) |

|

| Plinio Nomellini, The Red Nymph (c. 1904; oil on canvas, 101.5 x 84 cm; Goldoni Gallery, Livorno) |

|

| Plinio Nomellini, The Insurgents (1907; Genoa, Collezioni d’Arte Carige) |

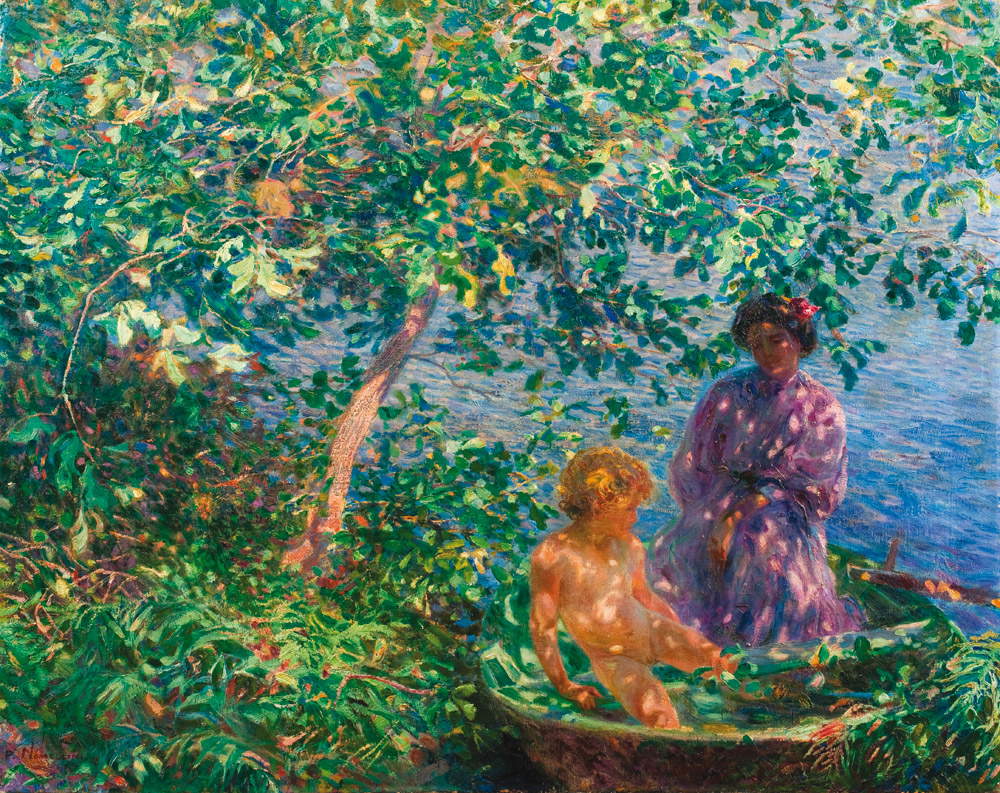

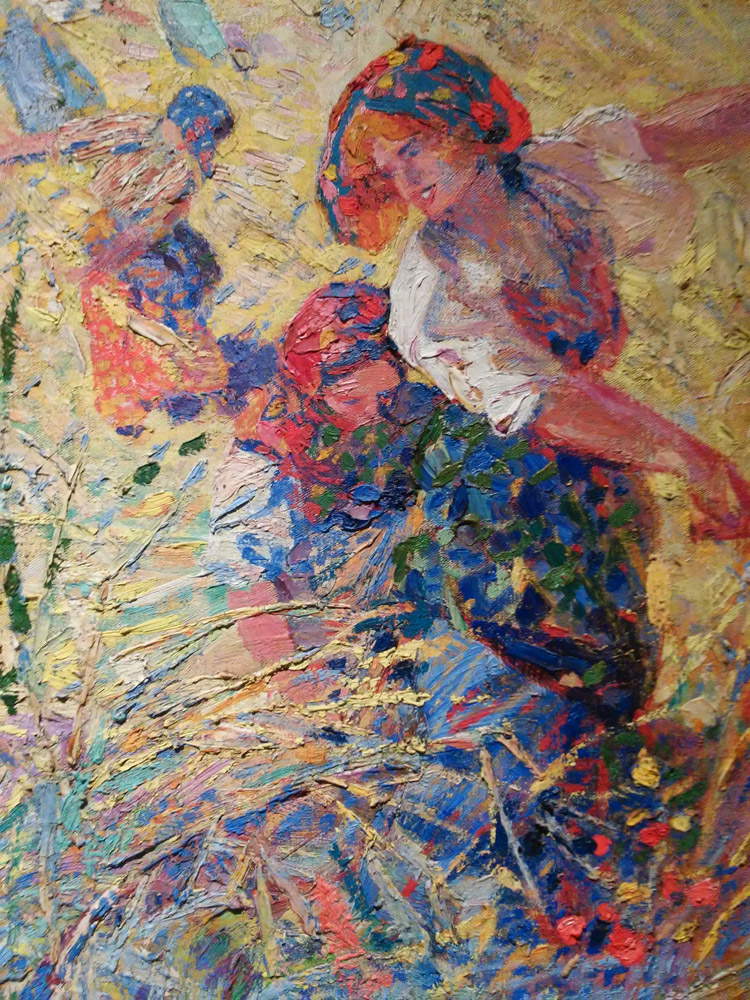

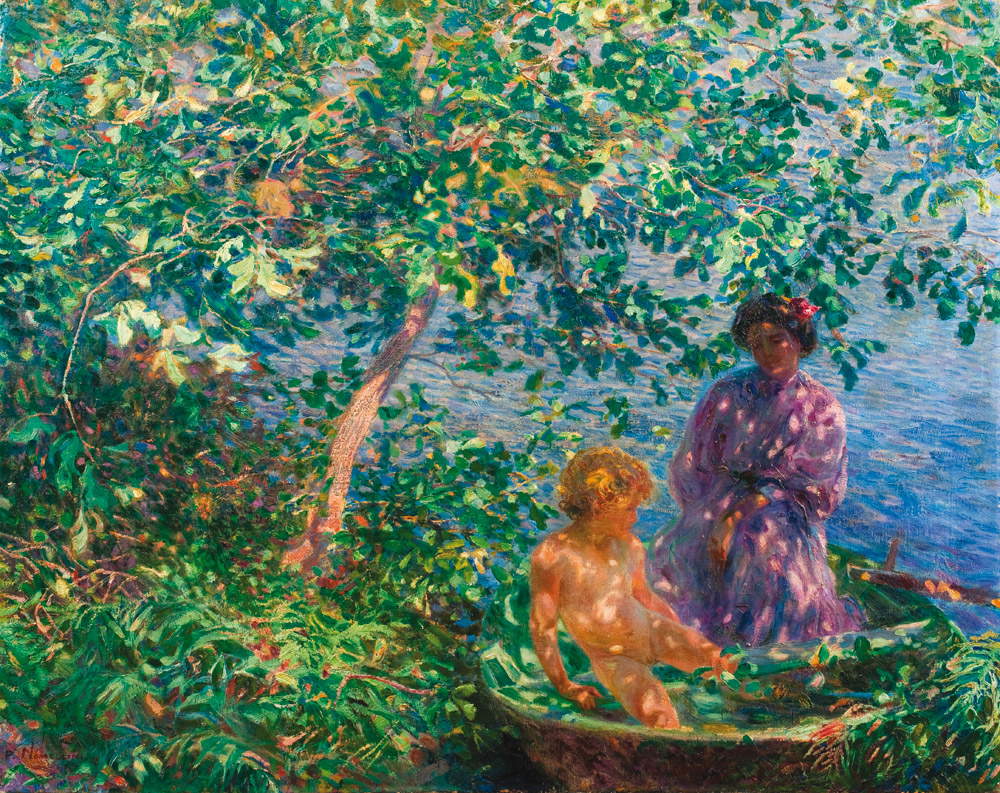

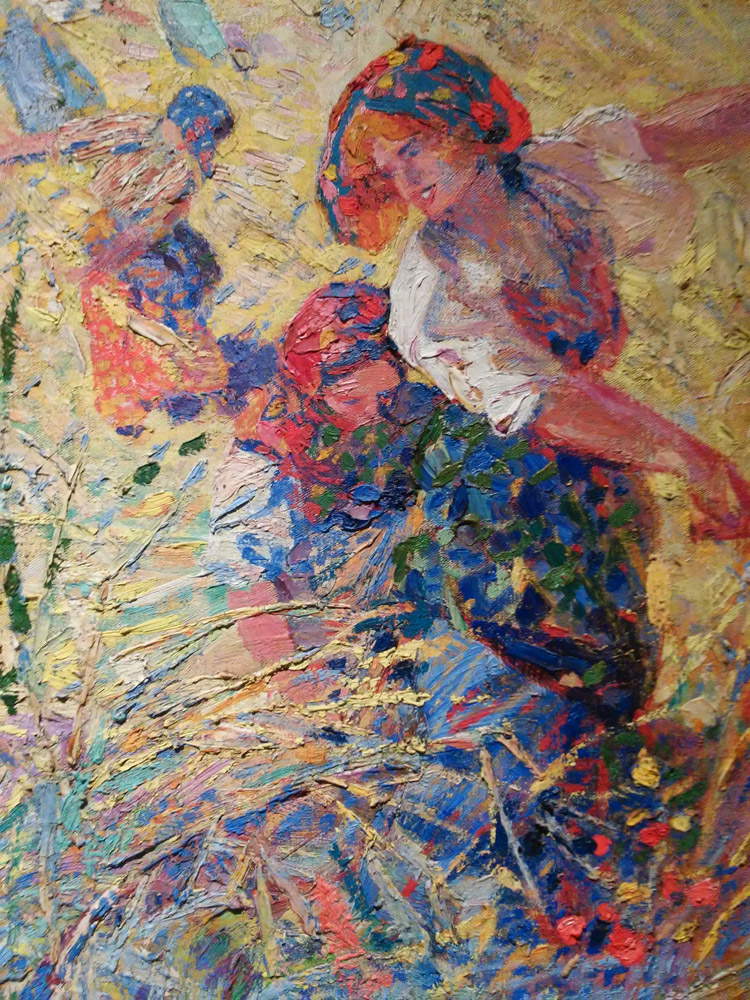

In that same 1907, Nomellini bought land near Viareggio: the painter resided for more than a decade in Versilia, before returning to Florence. The last rooms of the exhibition constitute a poetic journey into the most intimate and lyrical dimension of Plinio Nomellini’s art, which in Versilia was perhaps able to find its highest notes. It almost seems as if the artist wanted to continue to identify with the sweetness of a land that, roughly from the mid-nineteenth century, had begun to become a destination for restful summer stays. Exemplifying this new season is a joyous canvas, Baci di sole, whose protagonists are his wife and son Vittorio, playing under a leafy tree, sheltered from the summer heat: the kisses to which the title alludes are those that the sun lets filter through the branches of the tree and which Nomellini renders with a terse, evocative luminism, and mindful of Impressionist pasts, with the result that the painting becomes, writes Nadia Marchioni, “an extraordinary triumph of light and shadow, a celebration of the happiness of nature and of life itself, rendered on the canvas with a dense and vibrant pictorial matter, in a festive alternation of fringed brushstrokes and sometimes reduced to luminous filaments that chase each other across the canvas, creating an unrepeatable warp: the swirling movement of the vegetation, centered on the slender tree stem, subsides in respect of the familiar scene, where the actors are caught in a moment of indolent summer tranquility.” The landscape, the climate, the atmosphere, and the light of Versilia were particularly suited to the artist’s temperament and the lyrical notes of his painting: the Versilia season was thus particularly fruitful, even on a technical level. That “dense and vibrant pictorial matter” that the visitor gets to appreciate in Baci di sole, becomes even thicker and more energetic in paintings such as Messidoro and Mietitura, where the riarsi fields on the shores of the sea are and enveloped by a sultry and fiery light explode in swirls of mellow color that often acquires an engaging three-dimensionality, so that blades of grass and mowed ears of corn almost seem to spill out of the painting.

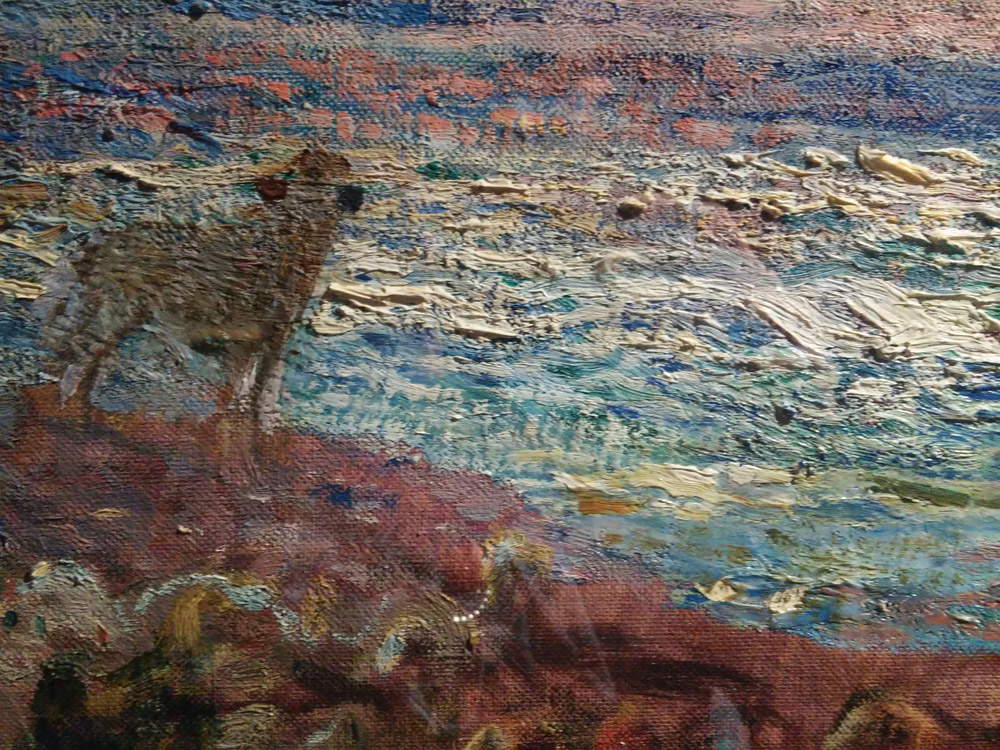

There is still room for Divisionist experiments(Little Red Riding Hood is an eloquent autumnal poem), but later in the years Nomellini’s brush will acquire a fluency hitherto unknown, and the last room of the Seravezza exhibition intends to document this further, very new turn for the Leghorn artist: however, more than in the paintings that celebrate the fascist regime and that will be the cause of his postwar condemnation, it is still in the works of light and the sea that it is necessary to find the dimension most congenial to the artist. If a painting such as Pascoli on the Sea almost seems to cast a glance back in time, with its snapshot character that nevertheless captures with precision the flocks of a shepherd approaching the shore of the sea illuminated by a ray filtering through the gray clouds, paintings such as Enrico Pea’s Theater in the Viareggio pine forest or the Corsaresca, while not entirely renouncing Symbolist accents, are distinguished by a free synthesis that builds the elements through sudden darts and brushstrokes that with unusual rapidity create geometric forms. They were the last achievements of an artist who, never for a second, had ceased, echoing Signorini’s words, to feel the need to break out of the ordinary.

|

| Plinio Nomellini, Baci di sole (1908; oil on canvas, 93 x 119 cm; Novara, Galleria d’Arte Moderna “Paolo e Adele Giannoni”) |

|

| Plinio Nomellini, Mietitura (c. 1911; oil on canvas, 85 x 114 cm; Genoa, Museo dell’Accademia Ligustica) |

|

| Mietitura, detail |

|

| Mietitura, the brushstroke |

|

| Plinio Nomellini, Little Red Riding Hood (1912-1919; oil on panel, 84 x 67 cm; Private collection) |

|

| Plinio Nomellini, Pascoli sul mare, detail (c. 1930; oil on canvas, 110 x 160 cm; Private collection) |

|

| Plinio Nomellini, Enrico Pea’s Theater in the Viareggio Pine Forest (1925-1930; oil on cardboard, 31.3 x 41.2 cm; Livorno, Goldoni Art Gallery) |

|

| Plinio Nomellini, La corsaresca (1940; oil on canvas, 148 x 115 cm; Livorno, Galleria d’Arte Goldoni) |

The Seravezza exhibition is a meritorious operation, presenting the public with an almost complete reading of Nomellini’s artistic journey: a pregnant and consistent reading that, presenting the public with unpublished and new works as well, makes use of a precise scanning strong of ninety works from prestigious Italian museums (some: the Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea in Rome, the Galleria d’Arte Moderna in Palazzo Pitti, the Galleria d’Arte Moderna and the Museo dell’Accademia Ligustica in Genoa, the Galleria Ricci Oddi in Piacenza, the Musei Civici in Pavia, the Pinacoteca “Il Divisionismo” in Tortona), probes with dedicated insights the main themes of the Leghorn painter’s production, insists especially on his relationship with nature and Versilia, and finds in his solid roots to the territory an additional reason to visit. All in all, an exhibition to be remembered and, if you will, even capable of arousing not a few emotions (especially if you know Versilia well), also accomplice to Plinio Nomellini’s bewitching brush. The catalog, about which it is necessary to point out the important absence of detailed cards and a bibliography, presents five high-level essays written by specialists in the art of the period: specifically, that of the curator summarizes Nomellini’s entire iter; Vincenzo Farinella ’s contribution clarifies the links with French naturalism with which Nomellini, according to the scholar, was able to familiarize thanks to the intermediary of Filadelfo Simi, and again Silvio Balloni’s essay sheds light on the relations between Nomellini and literature, Aurora Scotti Tonsini’s essay, as mentioned above, is an in-depth study of the meeting between the Leghorn artist and Giuseppe Pellizza da Volpedo, and finally the last essay, written by four hands, illustrates technical aspects of two youthful works.

Leaving the Palazzo Mediceo in Seravezza, therefore, one can take the road to the sea again: in about ten minutes one will find oneself in front of those views that Nomellini loved, of that sea that the artist tried to celebrate in the most varied ways, of the poetry of those landscapes that the painter wanted to bring back to the canvas according to his own very high sensitivity. To see with one’s own eye what the artist himself saw with his own, just a few kilometers from the exhibition venue, is a priceless completion of the itinerary of an exhibition that is certain to be included among the most successful of the year, nationwide.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools.

We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can

find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.