by Federico Giannini (Instagram: @federicogiannini1), published on 30/08/2017

Categories: Exhibition reviews

/ Disclaimer

Review of the exhibition 'Pintoricchio. Painter of the Borgias' in Rome, at the Capitoline Museums, from May 19 to September 10, 2017.

The visitor should not be fooled by the title that, on the surface, would seem to wink at the fiction audience, given the international resonance that the vicissitudes of the Borgias recounted in a recent and successful television series have had: Pintoricchio. Painter of the Borgias is a very serious exhibition, capable of blending with refined wisdom a purely popular soul and an interesting research project that reveals to the public an unseen Pinturicchio of the highest level. However, it is necessary to proceed step by step, because the exhibition, which is held in Rome on the third floor of the Palazzo dei Conservatori, and which is supported by a high-level scientific committee (a Pinturicchio specialist such as Claudia La Malfa is joined by the names of Cristina Acidini, Francesco Buranelli and Claudio Strinati, in collaboration with Franco Ivan Nucciarelli), begins by allowing the observer to familiarize himself as much with the historical context as with the art of Pinturicchio (real name Bernardino di Betto, Perugia, about 1454 - Siena, 1513). Two main objectives are pursued: first, to delve into the bond that united the Umbrian painter with Pope Alexander VI (born Roderic Llançol de Borja, Italianized as Rodrigo Borgia, Xàtiva, 1431 - Rome, 1503) and that led the artist to create for him one of the greatest masterpieces of the Renaissance, the decoration of theBorgia Apartment of the Apostolic Palace in the Vatican. The second, to present the rich body of studies that led to the reuniting of two fragments of a wall painting by the artist having as its subject theDivine Investiture of Alexander VI: a painting detached in ancient times, then divided, and later even inventoried by its owner with numbers far apart so that the fragments would appear as separate works. Part of the original turns out, moreover, to be untraceable: we know, however, what the work looks like from an early 17th-century copy by Pietro Fachetti (Mantua 1535 Rome 1613), on display in the exhibition.

The risk, in fact, was to perpetuate the memory of a work that aroused scandal and to undermine the owner’s reputation even centuries after it was made. The iconographic program of the painting envisioned Pope Alexander VI kneeling before the Madonna and Child in order to be invested by the latter with the role of pontiff, and thus the supreme guide of the Church: however, a rumor that we have to imagine circulating at the time of the events (the work was presumably painted around 1492, the year Rodrigo Borgia ascended to the papal throne with the name of Alexander VI), and “certified” a few decades later by Giorgio Vasari’s Lives, ended up conditioning the fortune of the work, and in part that of Pinturicchio himself. More specifically, at the time the rumor circulated that the Madonna had the likeness of Giulia Farnese, Alessandro VI’s mistress despite the heavy age difference between the two (in 1492, Alessandro VI was sixty-one years old, while Giulia was just seventeen): a condition that attracted numerous criticisms on the young woman, well summarized by the blasphemous epithet of sponsa Christi (“bride of Christ”) that was affixed to her by her more venomous contemporaries. In the 1550 edition of the Lives, as mentioned above, Vasari spoke of a work that depicted “above the door duna camera la Signora Giulia Farnese per il volto duna Nostra Donna: et in the same painting the head of it Pope Alexander,” referring unequivocally to the painting that, for reasons of damnatio memoriae, was soon censored, ever since the time of Alexander VI’s successor, namely his bitter rival Julius II, who abandoned the apartment in the Apostolic Palace because he could not tolerate the sight of the frescoes that so blatantly celebrated the Spanish pope and were so much talked about.

We will come later to discuss the painting specifically because, as mentioned above, the exhibition begins with other assumptions. The layout of the exhibition appears severely tripartite: a first part that serves as an introduction to the historical context within which the events of the protagonists moved is followed by a second part that aims to present the visitor with meanings and iconographic sources of theBorgia Apartment, and finally a conclusion that leads the audience to the discovery of the “mystery unveiled” of Giulia Farnese. However, one does not feel sharp caesuras between the different sections. The exhibition, in fact, takes on the contours of a pleasant narrative that proceeds step by step, with great consistency, and availing itself of a layout devoted to sobriety: the works are arranged directly above the white walls of the rooms reserved for temporary exhibitions of the Capitoline Museums and are accompanied by panels, also white, particularly well cared for and thorough.

|

| Last room of the exhibition Pintoricchio. Painter of the Borgias. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| Set-ups of the exhibition Pintoricchio. Painter of the Borgias. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

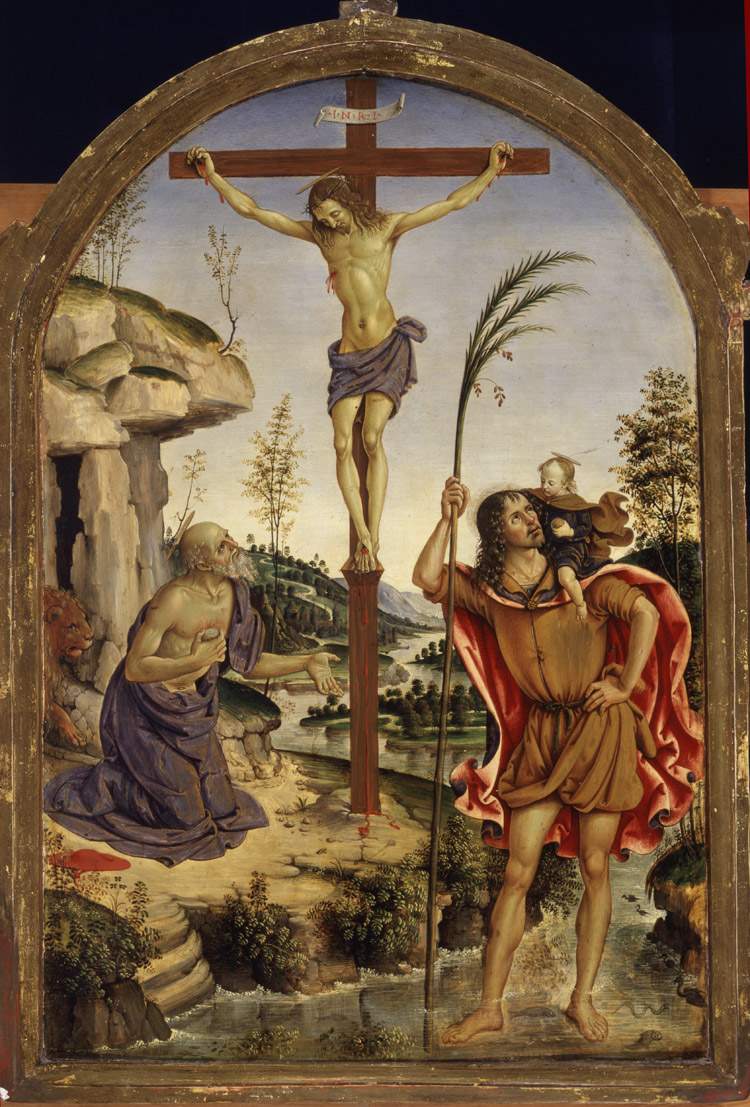

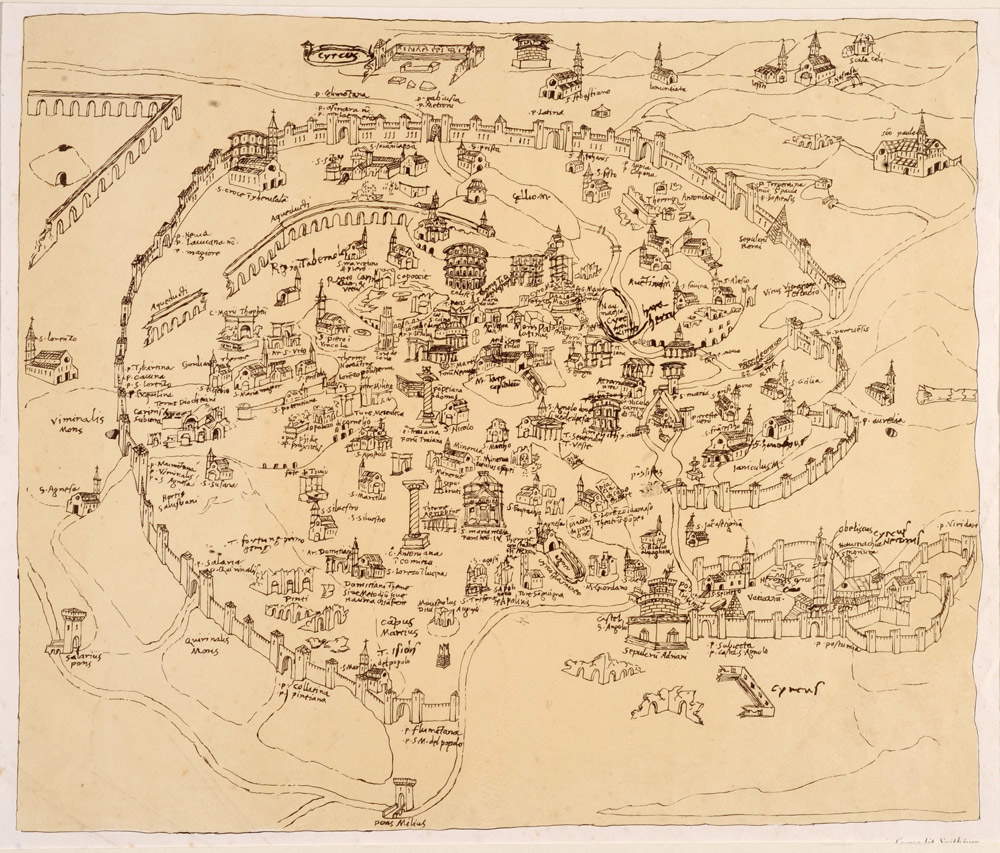

Upon entering, one immediately comes across a work by Pinturicchio, arranged at the opening of the itinerary so that the visitor can immediately grasp the peculiarities of the Umbrian artist’s style. It is a Crucifix between Saints Jerome and Christopher, an early work datable to about 1477, almost certainly a compartment of a portable altarpiece, and particularly significant since it foreshadows the future developments of Pinturicchio’s art, anticipating moments that we will find in the frescoes of the Apostolic Palace and in the paintings of the late fifteenth century: the delicacy of Perugia revisited, however, according to those nervous forms that will become a typical specification of Pinturicchio’s art, the descriptive minutiae of the landscape of Flemish ancestry, the light golden highlights, traits to which is added the marked interest in the natural datum, proper to the young Pinturicchio, which here is evident from the care with which the artist describes the little beasts (fish, palmipeds, water snakes) that populate the river in which Saint Christopher bathes. In those very years Pinturicchio, who had begun to make a name for himself in Umbria with the most important local patrons, had moved to Rome where he began to make a name for himself at the papal court. The city, at the time, was in great ferment: the popes who succeeded one another from the middle of the century onward began a massive work of rearrangement of many of the buildings of a Rome that, as the nineteenth-century chromolithograph, made from a 1474 drawing by Alessandro Strozzi reproducing a plan of mid-fifteenth-century Rome, still retained its medieval appearance (and this is more or less how it is drawn in the map that it must have presented itself to Pinturicchio’s eyes). A strong impetus was provided by Popes Sixtus IV and Innocent VIII, the immediate predecessors of Alexander VI: the former raised the hospital of Santo Spirito from decay, had the churches of Santa Susanna and San Vitale, among others, fixed up, had Santa Maria della Pace built, and above all initiated the work on the Sistine Chapel, which he named after him. The second distinguished himself in the field of the arts by calling the great Andrea Mantegna to Rome in order to entrust him with the decoration of the chapel and sacristy of the Palazzetto del Belvedere in the Vatican: it is likely that Pinturicchio also looked to his works at the time the Venetian artist stayed in the city in 1490.

Closing the first section are three portraits of the Borgia family: the most famous is that of Altobello Melone, a portrait of great quality depicting a condottiere traditionally identified as Cesare Borgia, the Valentino, the son the pope (then cardinal) had by his mistress Vannozza Cattanei (the portrait of her we observe in the exhibition is by Innocenzo Francucci da Imola). However, the presence of the portraits of Valentino and Vannozza Cattanei seems incidental since their figures in the exhibition are not explored in any depth. More functional, on the other hand, in accompanying us toward the second part of the exhibition itinerary is the portrait of Alexander VI attributed to Titian: it is around him that the continuation of the narrative unravels, focused, however, not so much on the Alexander VI skilled political minstrel, but on the role that Pinturicchio’s art assumed in the celebration programs that the pope intended to pursue, and obviously on the events that the works of Borgian patronage went through after the end of Alexander VI’s pontificate. On the reasons that induced Rodrigo Borgia to choose Pinturicchio in particular, Cristina Acidini intervenes with her essay in the catalog, which talks about how the Umbrian artist had already worked in the Vatican both for Sixtus IV (he was Perugino ’s collaborator in the works of the Sistine Chapel: we do not have much knowledge of exactly what his role had been; what is certain is that at the time he was already a painter “endowed with a precise physiognomy of his own”) and for Innocent VIII (he worked on the Belvedere Palace together with Piermatteo d’Amelia). Although it is not yet clear how painter and pontiff had come into contact, it is to be expected that the pope must have taken notice of Pinturicchio because of the outstanding results he had previously achieved, his mastery of different techniques, and his ability to deal with both sacred and profane themes with ease and wisdom: “Over the span of his experience,” Cristina Acidini points out, “Pintoricchio had shown himself at ease, on the basis of his knowledge of the painting and sculpture of the revered Ancients, but also of his continual updating on the most appreciated achievements of the Moderns, in organizing pictorial apparatuses of entire rooms with views of natural landscapes with beautiful cities and noble monuments. He knew how to compose complex stories, populated with figures with harmonious features and impeccably distributed colors, as well as to organize reviews of isolated images with an evocative archaeological aura, taking care of the details-where autographs-with his finesse as a miniaturist.”

|

| Pinturicchio, Crucifix between Saints Jerome and Christopher (c. 1477; oil on panel, 59 x 44 cm; Rome, Galleria Borghese) |

|

| Josef Spithöver (chromolithograph), F. Fazzone (drawing) from Alessandro Strozzi, Plan of Rome in the 15th Century (1879; chromolithograph, 289 x 342; Rome, Museo di Roma, Gabinetto delle Stampe) |

|

| Altobello Melone, Portrait of a Gentleman (Cesare Borgia?) (c. 1513; oil on panel, 58.1 x 48.2 cm; Bergamo, Accademia Carrara) |

|

| JAttributed to Titian, Portrait of Alexander VI Borgia (c. 1535-1545; oil on panel; Private collection) |

Such exceptional skills found natural fulfillment in the frescoes of the Borgia Apartment, some of which are present with reproductions in the next section of the exhibition (the invitation, however, is to go to the Vatican Museums to admire the originals). The sumptuous apparatus, aimed at magnifying the Spanish pontiff by legitimizing his power also on a mythological basis, avails itself of a complex iconographic program that draws heavily from the figurative repertoire of classical art, and the exhibition must be credited with making evident these returns that often take on the contours of direct quotation. But the artist did not simply take up classical motifs. The intention was to make the Borgia Apartment, on which Pinturicchio worked roughly between 1492 and 1494, a new Domus Aurea: Nero’s grand residence had been rediscovered in those years, and the Umbrian painter was the first to “bring back to life from beneath the ground,” Claudia La Malfa explains in her catalog essay, “the style, the pictorial and stucco technique, the relief, the geometric partitions, the decorative elements interwoven with narrative ones, the marbles and incrustations of various kinds, and finally the grotesques of the grandiose palace built by the Roman emperor Nero on the Colle Oppio in Rome.” We can imagine that this revival was dictated by the celebratory needs of Alexander VI: the intellectuals active at his court (above all Annio da Viterbo) charged Pinturicchio with the not easy task of making the myths of ancient Egypt, those of classical Rome, and, of course, the stories of Jesus Christ and the saints coexist in a single iconographic program. The political premise behind the project, speculated Franco Ivan Nucciarelli in his lengthy essay on Pinturicchio in 1998, was to suggest, in the anomalous situation of a monarchy not based on dynastic continuity, the idea that the Borgias might pose as the continuators of the emperors, pursuing “the will to transform the Church State into a hereditary principality in the hands of one family.” Whatever the motivations behind the cycle, what is certain is that the frescoes that comprise it ended up having considerable weight in determining the taste of the time: the scholar Jürgen Schulz, in a 1962 article, went so far as to assert that Pinturicchio’s influence extended even to Raphael ’s Stanze and Michelangelo ’s frescoes in the Sistine Chapel.

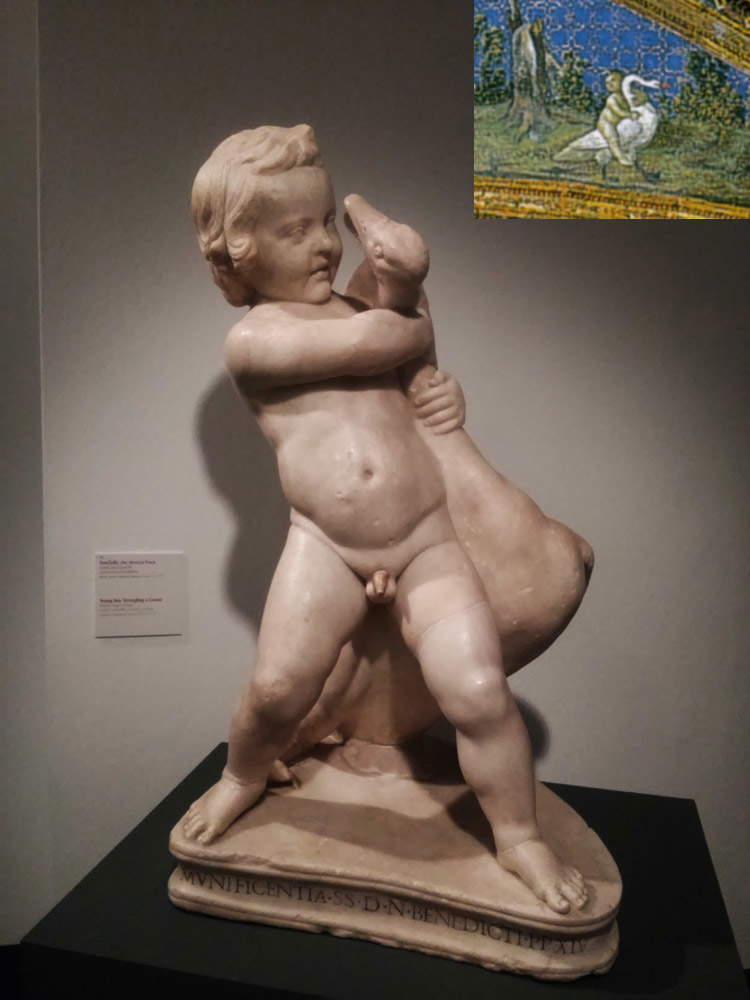

And equally certain is that, for the artist from Perugia, classical art had been a continuous source of inspiration. The figure of Saint Barbara in the Hall of Saints in the Borgia Apartment is a perfect derivation from a fleeing Latona on display in the exhibition, as is an Aphrodite who served as a model for the Susanna we find in the same room, or like the Putto choking the goose directly mentioned in one of the frescoes in the vault of the room (those celebrating the myth of Isis and Osiris), and again the Cerva that we see taken up again in the scene of Susanna and the Old Men, or the sarcophagi with sea processions and victories holding clipei, inspirational motifs for the putti that, in the Apartment, support the Borgia coat of arms.

|

| Frescoes in the Borgia Apartment in the Vatican. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte. |

|

| Putti holding the Borgia coat of arms in the Borgia Apartment. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte. |

|

| Sarcophagus with marine thiasos (first half 3rd cent. AD; inscription 4th-5th cent. AD; insular marble, 67 x 214 x 73 cm; Rome, Capitoline Museums) |

|

| Child choking loca (middle imperial age; possibly Pentelic marble, height 93.5 cm; Rome, Capitoline Museums, Palazzo Nuovo). Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| Louvre-Naples type statuette of Aphrodite (first half 1st cent. AD; Pentelic marble, height 118 cm; Rome, Capitoline Museums, Centrale Montemartini). Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| Statuette of Latona on the run (early imperial age; Luna marble; Rome, Capitoline Museums, Centrale Montemartini). Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| Statue of a doe (late Hellenistic age; insular Greek marble; Rome, Capitoline Museums, Centrale Montemartini). Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

Pinturicchio’s great refinement is finally revealed, as is the “myth” of Giulia Farnese, in the last section of the Roman exhibition. Of the painting that once adorned the Appartamento Borgia (and which was first covered under the pontificate of Pius V, just at the time when the second edition of Vasari’s Lives that so damaged the artist’s fame was being published, and then detached under Alexander VII) only two fragments remain, those depicting the Madonna and Child. The portrait of Alexander VI was probably destroyed when it was detached: evidently Alexander VII (born Flavio Chigi, pope from 1655 to 1667), though not scandalized by the legend that hovered around the painting, did not want to pass as the pontiff who would rehabilitate the memory of Rodrigo Borgia. Only the left hand of Alexander VI survives, which we see in the fragment known, precisely, as the “Child Jesus of the Hands,” tracked down in 2004 by Nucciarelli, who had it purchased by the Guglielmo Giordano Foundation of Perugia. The other fragment, the one in which we observe the sweet face of the Madonna purported to represent Giulia Farnese, is exhibited and published for the first time on the occasion of the Capitoline exhibition.

The two fragments are nourished by the comparison with the Madonna of Peace lent by the Pinacoteca Civica of San Severino Marche: executed around the same years (we are around 1489), it is a masterpiece of executive refinement, decorative elegance, sweetness but also monumental solidity. These are all characteristics that appear to us by observing above all the Madonna and Child, but also the angels accompanying them, the landscape in the background, as well as the client, that is, the apostolic protonotaio Liberato Bartelli, depicted with that truthful likeness that Pinturicchio, as the skilled portraitist that he was, knew how to instill in the subjects to be immortalized. From a comparison of the faces of the two Madonnas it will immediately become clear that they belong to the same type, which characterizes all the similar works created by the Umbrian painter in this period: a comparison that should leave no doubt that the Virgin, rather than representing a real person, is to be considered as an ideal model. What is revealed before our eyes, in the words of Francesco Buranelli, is an “extremely ascetic and unfinished face, full of loving concentration and absorbed complacency towards the scene he is witnessing, without any portrait research”: if the artist had really wanted to give a realistic connotation to the face of the Madonna, he could have done so without any problem, also by virtue of the fact that the paintings of the Borgia Apartment are full of portraits of contemporary figures. This is a painting that implies another meaning, as Fachetti’s copy displayed in the exhibition lets us fully understand. What Alexander VI had in mind was more than a simple homage to the Madonna, it was more than an ordinary devotional painting in which the patron was depicted kneeling at the feet of the two deities. Particularly revealing are the gesture of the pontiff caressing the Child’s foot, the latter’s blessing, and the globe he holds in his hands. It is a kind of crowning of the whole program of the Borgia Apartment, which has salvation by faith as its main theological theme. Salvation is possible only through Christ, and Alexander VI is his vicar on earth: his caress represents the moment when Rodrigo Borgia accepts the high mission with which Jesus invests him. The globe represents, of course, the universality of Christ’s message, but it also symbolizes the universality of Alexander VI’s mandate.

|

| Pietro Fachetti, Divine Investiture of Alexander VI, copy from the wall painting by Pinturicchio (1612; oil on canvas, 115.5 x 124 cm; Private collection) |

|

| Pinturicchio, Madonna, fragment of the destroyed Divine Investiture of Alexander VI (c. 1492-1493; wall painting within seventeenth-century frame, 39.5 x 28.5 x 5 cm; Private collection) |

|

| Pinturicchio, Child Jesus of the Hands, fragment of the destroyed Divine Investiture of Alexander VI (c. 1492-1493; wall painting within seventeenth-century frame, 48.6 x 33.5 x 6.5 cm; Perugia, Guglielmo Giordano Foundation) |

|

| Pinturicchio, Madonna of Peace (c. 1489; oil on panel, 143 x 70 cm; San Severino Marche, Pinacoteca Civica Tacchi-Venturi) |

In essence, the painting is particularly representative of the ambitions of a pontiff who considered himself chosen by Christ himself, rather than by a conclave of cardinals: a celebration and at the same time a warning, in keeping with the character’s temperament. Of course: today we are attracted by the ethereal beauty of the very young Madonna, the tenderness of the Child, the technical virtuosity of an exceptionally talented painter, a “trend setter” ante litteram, and the preciousness of his brush that finds a valuable ally in the stucco decorations covered with pure gold that give a tangible three-dimensionality to the painting. But it is also necessary to trace the work back to its theological and political significance, net of legends that, even with all their load of undeniable fascination, have little or nothing to do with the history of art. And in this skillful work of unmasking a centuries-old legend based on rumor, the exhibition succeeds very well: rigor is, after all, what is required of an exhibition. However, it is equally true, and the exhibition at the Palazzo dei Conservatori proves it, that rigor can also marry very well with a skillful narrative that, without going off the rails of scientific seriousness, soundness and logical consistency (it can be said that there is not, in Pintoricchio. Painter of the Borgias, a single work out of place), can make itself deeply compelling to any visitor.

It’s just a pity that more could have been done on the catalog: interesting for taking stock of the relationship between Pinturicchio and the Borgias (Cristina Acidini and Claudia La Malfa’s extensive essays reconstruct the undertaking of the Borgia Apartment with great care, while Francesco Buranelli’s contribution is the first ever dedicated to the two fragments of the ancient wall painting), it suffers, however, from cards that are not always exhaustive and detailed. The card on Luca Longhi’s Lady with a Unicorn (featured in the exhibition because they wanted to see a portrait of Giulia Farnese in it), for example, is summarized in just twelve lines, and the only bibliographic source cited by the compiler, namely Claudio Strinati, is a contribution by himself, dating back to 2014, when instead Longhi’s Lady is a painting that has a far more substantial bibliographic history, which also includes an in-depth article by Giulia Daniele published in Storia dell’Arte (thus in a well-known and easily accessible scholarly journal) in 2013. There are much better edited and in-depth entries, of course, but perhaps it would have been better to be faced with a more uniform and leveled upward apparatus. Beyond that, it cannot be denied that this is a very useful and thoughtful publication that, like the exhibition, unquestionably advances knowledge about the art of one of the great protagonists of the Renaissance.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools.

We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can

find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.