The story of the Demoiselles d’Avignon, which is among the founding masterpieces of twentieth-century art, can be taken as a very eloquent example of the damage that, in the field of the arts, can be caused by the most boorish, most obtuse, most reactionary nationalism. It is well known that the painting, at first, was not understood: it was accused of immorality and for a long time found no buyers, so much so that the canvas had to lie rolled up in Pablo Picasso’s studio for eight years after its first exhibition. It was 1916 when the Demoiselles was first exhibited, at the Salon d’Antin, and the painter was forced to wait until 1924 to find a buyer, thanks to the intermediary and interest of André Breton and Louis Aragon. Picasso, by the 1920s, had already become a rich and famous painter, and had struck a deal with Jacques Doucet, one of the fathers of French fashion and a great art collector, for a sum that was not very high: 25,000 French francs, roughly 26,000 euros today. The work was worth at least ten times as much: art historian John Richardson, a Picasso scholar, believed that the artist had accepted a sale at a reduced price as a result of a promise by Doucet, namely that he would allocate the Demoiselles, by testamentary will, to the Louvre collections. Doucet considered himself, at least according to Breton, the only collector capable of persuading France’s largest museum to accept an avant-garde work. The problem, however, was that in the end Doucet did not include the Demoiselles in his will, with the result that the painting was later sold by his widow to the Seligmann Gallery in New York. And it was eventually purchased by MoMA, where today millions of people admire it. Far away from France, far away from the land where the work was made, far away from the country that had had the opportunity to retain in one of its public museums one of the cornerstones of modernity.

Why was the work not left in the Louvre despite promises? The idea of Jean-Hubert Martin, a curator who has worked for many years in France’s national museums, is that France was unwilling to accept the Demoiselles. There is a passage in René Gimpel’s memoirs in which the Cubists’ historical dealer laments that “the Louvre refused its Picasso, which is the most beautiful painting in the world. At the Louvre, at the Luxembourg, no one in the official management group wants to hear about Picasso. He is hated.” We have to imagine that, in Doucet’s chats with museum management, the collector sensed the total lack of interest in the Demoiselles, and realized that any bequest would be rejected. Martin, in the exhibition catalog Picasso the Foreigner, is explicit: "The departure of Les Demoiselles d’Avignon for the United States is indicative of the artistic conservatism rampant in France. In the name of nationalism and French genius, the institutions, under the tutelage of the Académie des Beaux-Arts continued this traditionalist policy." This is not an idea formulated through the filter of an easy presentism: it is a historically substantiated hypothesis, linked to a climate that was breathed not only in France, but also in Italy (one wonders why, in our public museums, it is very rare to find Cézanne, Van Gogh, Impressionists, Picasso themselves: the ruling class that governed museums in Italy in the first decades of the twentieth century was certainly no sharper than the French), a hypothesis that also fits well with Picasso’s personal history, told in the most uncomfortable details by the Palazzo Reale exhibition, the third stage of a project born out of a study by curator Annie Cohen-Solal, which began in 2021 at the Musée National de l’Histoire de l’Immigration in Paris, then continued in New York at Gagosian, and finally came to Italy, to the Palazzo Reale in Milan.

Annie Cohen-Solal’s is a project aimed at bringing out a Picasso who is little or not at all told, a Picasso who, for almost his entire existence, even when he was at theheight of success, even when his earnings had enabled him to buy a chateau in Normandy, had to live, even with some suffering, the condition of a foreigner in the age of nationalism, in a society, that of early 20th-century France, that was strongly xenophobic. The stigma that had branded Picasso, indeed, was triple: foreigner, leftist extremist, and avant-garde artist. And the paradox is that Picasso continues to suffer torment even in death, since today his figure is tarnished by another stain, which has to do with his relationship with the female sex: “a monster,” Adrian Searle, critic of the Guardian, bluntly called him in a survey his newspaper had conducted on Picasso himself, asking several scholars whether it is appropriate today to reconsider the art of the father of Cubism in the light of his less edifying human sides. A monster, yes: a macho driven by an irrepressible predatory instinct, a manipulator, a narcissist: yet, “the fact that he was a horrible human being is part of his complexity,” Searle concluded, with the result that “it is not possible to have Picasso without Picasso.” One wonders, then, how much his biographical background, how much his past as a police-attended outcast, how much his status as a de facto stateless person opposed even by the motherland at the time of the Franco dictatorship affected his temperament, his emotional sphere. Are Picasso’s reprehensible weaknesses a result of his fragility? Interesting question, which pertains more to psychology than to art, and yet inescapable if one wants to ask to what extent the human being should prevail over the artist. This is not, of course, clumsy justificationism: it is simply a matter of probing all sides of that complexity that must be recognized behind every Picasso work.

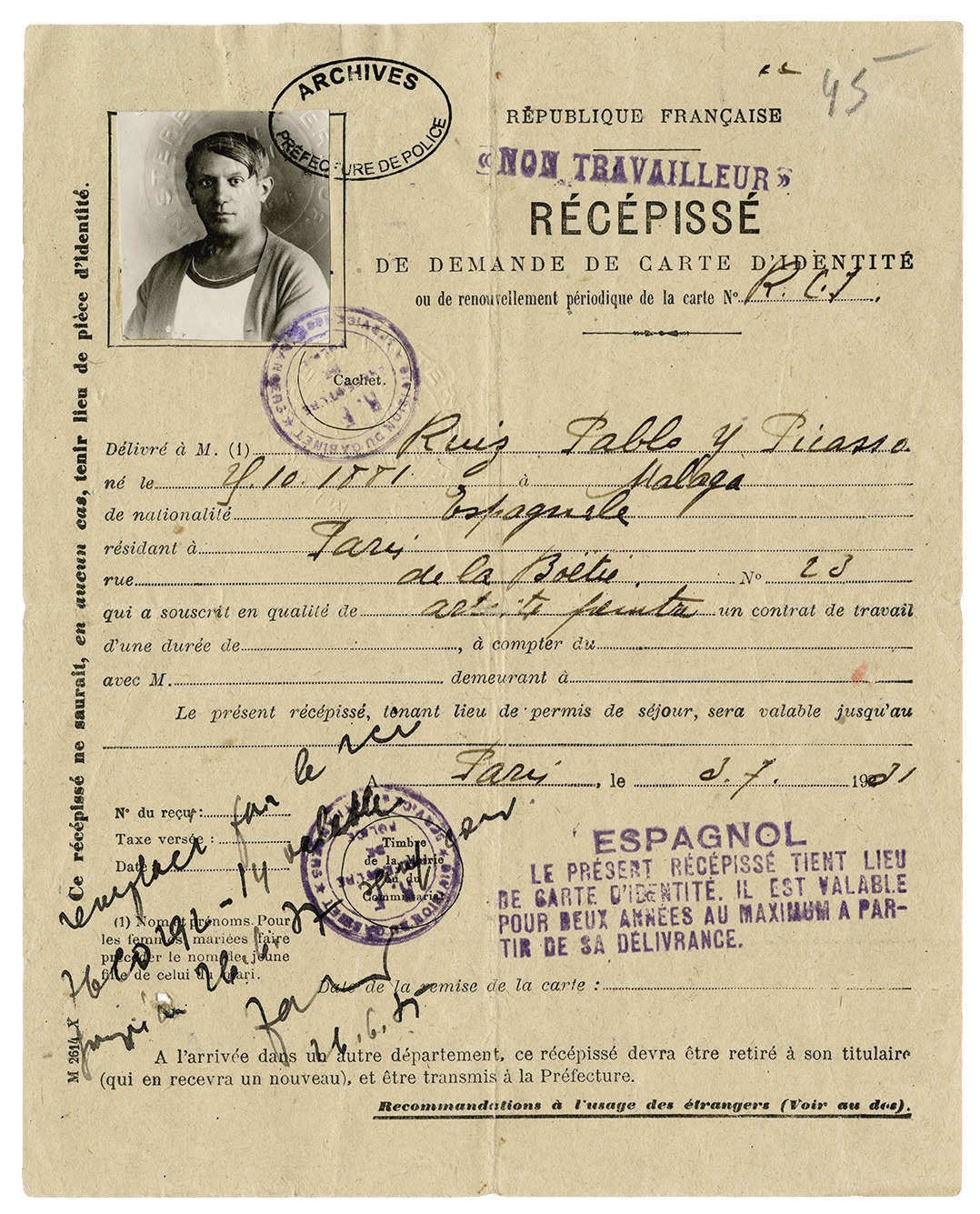

The Palazzo Reale exhibition then becomes a kind of biographical narrative that, by the express wish of the curator, almost entirely omits any formal analysis. Although, of course, it is logical to link to Picasso’s personal background not only his choices of subjects, which especially in the early stages of his career are conditioned by his loosely framed life, but also his experiments, which are reflective of his interests. Picasso’s story is, fundamentally, the story of a migrant, of a young man who, at the age of eighteen, leaves his country to move to a country he does not know, where they speak a language he does not know, and where he has no points of reference except some of his compatriots, a group of Catalan anarchists (the most famous are the painters Santiago Rusiñol and Ramón Casas, the others being Carles Casagemas, Pere Romeu, Hermen Anglada-Camarasa, Frederic Pujulà, Joaquim Mir, Ramon Pichot) who welcomed him to Montmartre, now a good, upscale residential neighborhood, in some areas obviously touristy, but at the time a rundown suburb, a neighborhood with an unsympathetic name, a kind of ghetto without barriers for immigrants, drifters, delinquents, the poor, where it became dangerous to wander around once night fell. For an immigrant, early 20th-century Paris is a repelling, hostile city (Maurice Barrès, who at the time was still the leader of French nationalism, wrote in 1898 that “the foreigner, like a parasite, poisons us”), so much so that Picasso would need four sojourns before his decision to settle here for good in 1904, the year he took lodgings at the Bateau-Lavoir, a tumbledown mansion on the slopes of the Montmartre hill, a single source of drinking water for thirty housing units. Paris, along with Picasso, is perhaps the real protagonist of an exhibition where the works often take second place to the narrative. A seductive and sullen city, a noisy and plural metropolis, lively and fearful, divided between a suburbs where a dense, fertile swarm of artists from all over Europe (and some even from further afield) who are writing the foundations of ’modern art, and a bourgeois center that has nothing to do with those frayed margins where life moves between the dilapidated ateliers of artists, the cafés where poets, singers, and painters hang out, the streets where policemen are busy every day chasing drunks, petty thieves, and migrants who bivouac wherever they can.

Here then, the production of these years abounds with the subjects most easily associated with the early Picasso: the poor, the harlequins, the acrobats, of course the friends, the portraits of the Paris that the young Spanish artist frequented (above all Max Jacob, one of his few French friends, perhaps the first native willing to lend him a hand). These are the first subjects encountered in the exhibition, visual translations of Picasso’s first impact with the city. All sketchily drawn on paper, traced with sparse but precise and sure markings over sheets of modest paper, notes that Picasso jotted down simply by looking around. It is especially with the acrobats that the young Picasso tends to identify himself, and not only because they were wanderers and outcasts like himself: the circus performers of early twentieth-century Paris were mostly Italian, and Picasso was of Italian descent (the surname with which he would choose to identify himself, the surname by which he went down in history, is not his father’s: it is his mother’s, and she is from Liguria), although his acrobats are not connoted, they do not have an identity and neither could they have one, since Picasso himself is difficult to define. Nor are they a way of carrying on a kind of anti-bourgeois protest, which is why other artists and literati of the time devote attention to acrobats: Picasso’s jugglers, wrote Emily Braun, “are part of a poetic mythology, but in reality [...] they are non-citizens: a group of vagabonds in the age of modern nation-states.” It could be said that even the early Cubist experiments, which in the exhibition are encountered soon after, are the product of Picasso’s constant wandering, physical and ideal: the decisive summer in Gósol, a remote village in the midst of the Pyrenees where even the state struggled to arrive, connects the artist to an archetypal simplicity rooted as much in Romanesque art as in the modesty, frugality, and extreme thriftiness that is typical of mountain peoples. His frequentation of the Parisian suburbs put the artist in a position to open himself without prejudice to African art and to the productions of outsiders: for that matter, Picasso’s esteem, at once ironic and sincere, for Henri Rousseau is well known. Being away from the academies and its circles freed his mind, deprived him of any conditioning, and allowed him to look with supreme interest at all those artists who tended to be excluded from institutional events, but who were introducing new ways of seeing reality. This is how cubism was born.

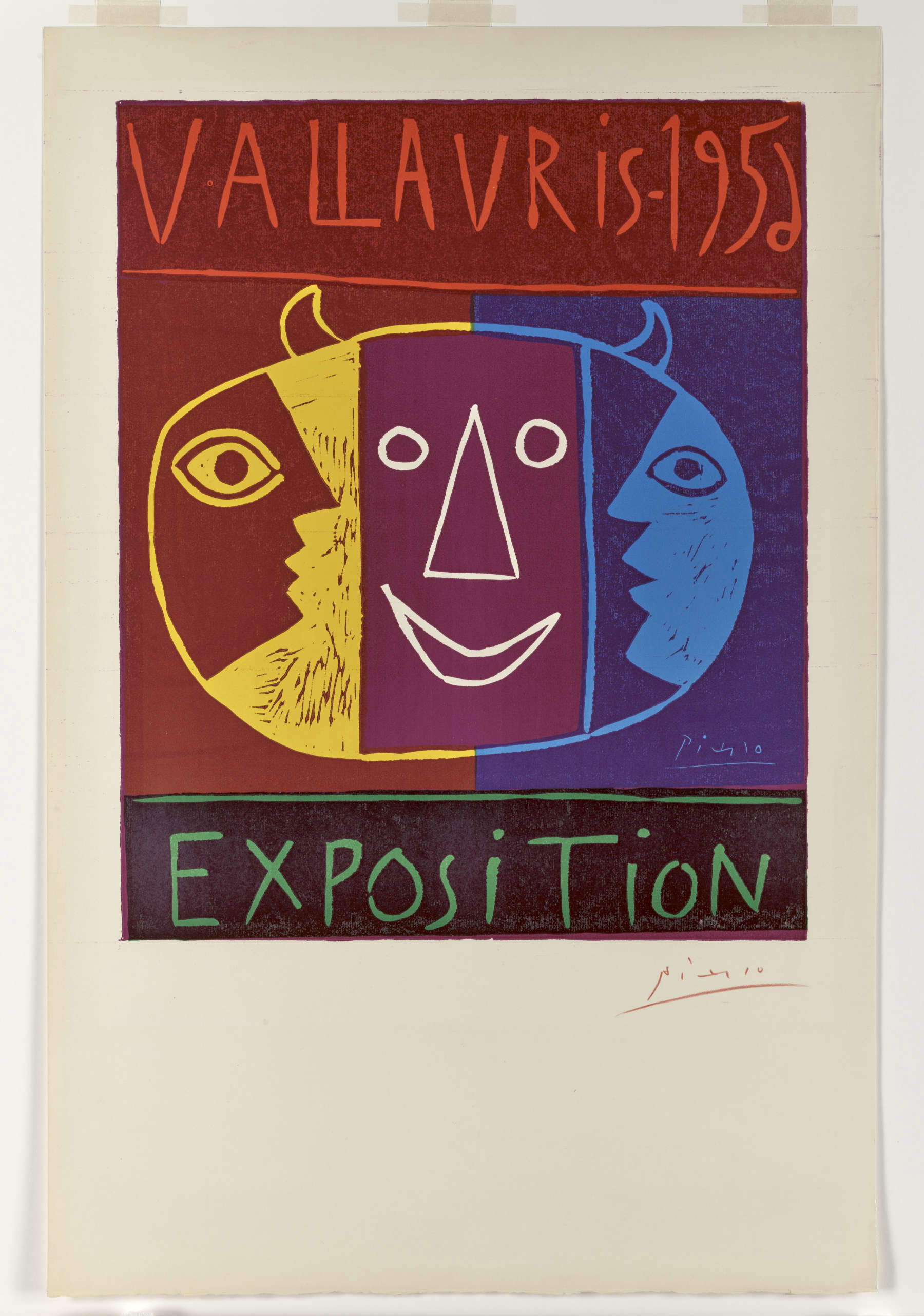

The evolution of Picasso’s art is followed by the exhibition in parallel with the private events that marked his life as an immigrant: the massive confiscation (some seven hundred Picasso works) from his art dealer, the German Daniel Kahnweiler, at the outbreak of World War I (France and Germany are on opposite sides), the need to reinvent himself and attempt experiments as a stage designer in collaboration with Djagilev’s Ballets Russes, thepolitical engagement with the Spanish Republicans and the Guernica enterprise, the success among American, German, and Russian collectors, the move from Montmartre to the neighborhoods of bourgeois Paris (there are also the drawings in which Picasso had portrayed his new apartment in rue La Boétie), the rejection of the request for naturalization submitted in 1940 to the Ministry of Justice of France, until the postwar years, during which Picasso, perhaps for the first time in his life, can enjoy full recognition, especially in the aftermath of the entry of a nucleus of his works to the Musée National d’Art Moderne: it is 1947 and finally the artist can say that he is adequately represented in a first-rate French museum. Along the way, it happens to have the feeling that the works are an accessory, at times one can almost feel a disconnect between the narrative and the images (it will then be useful to specify that the American leg of the exhibition was made with American works, while in Milan one can admire a single block of works from the Musée Picasso in Paris, a circumstance nevertheless made possible by the fact that Picasso was one of the most prolific artists in history): it has been said, moreover, that the curator, a sociologist and historian, has put formal aspects in the background, and this is probably the main flaw of an exhibition that opens to the visitor like the pages of a history book rather than an itinerary through Picasso’s art. A history book that is nevertheless necessary to probe in depth the complexity of an artist who, in his condition as a “foreigner,” had never had the opportunity for such vertical insights into his own status. Relevant, however, is the emphasis, toward the end, on a less investigated production, that of Vallauris and the south, where the artist, the curator informs us, “rediscovers the historical and cultural depth of that Mediterranean space of which he has always been a part.” It is perhaps the sunniest part of his work: the Plat aux trois visages that has been chosen as the exhibition’s guiding image belongs to this phase, a print in which Picasso inserts three faces within a tondo. On the left a profile that seems almost hallucinated, interpreted as the stranger. On the right a face with a more classical profile, that of the “native citizen” in Annie Cohen-Solal’s reading. And in the center a mocking devil with horns, the métoikos, the metecos, the free foreigner who, however, could not fully participate in the active life of his host country. Métèque, in French: it was also the name by which the community of foreign artists in Paris sometimes used to call themselves. It seems that Modigliani once wondered what Paris would be like without the métèques.

Who then was Picasso? How could one define him? A Spanish, French, Catalan, Andalusian, European artist? A foreigner, as per the title of the exhibition? Of course, one can frame him in such a cursory way to give him a label (entirely legitimate), but the question is decidedly more complex: the reality is that Picasso subverts any kind of “rigid identification by approaching borders and crossing them, as he had learned to do during his formative years and wanderings to the borders of Catalonia” (so Peter Sahlins). To link the figure of Pablo Picasso to the problem of identity is to move from art history to mythography. Identity, the sociologist Francesco Remotti wrote a few years ago, “is a myth,” and “to realize that really identity is in no sense at hand, and that it is foolish to want to grasp and conquer it by being it outside the band of possibilities, is to distance oneself from this myth of modernity and in this way gain a place from which one can better observe and analyze it.”

Pablo Picasso was an open artist, an artist who knew how to move in different contexts, knew how to draw from different sources, an artist who was certainly tied to certain places (Andalusian childhood, youth in Catalonia, maturity in Paris), but who had such different experiences, such contradictory experiences that he became a figure far from any kind of fixity. And mutability, we know, is as far removed from the traditional concept of “identity.” Are we then willing to give up considering the figure of Picasso by tying him to the problem of identity? This, perhaps, is the ultimate instance of the Palazzo Reale exhibition.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.