by Federico Giannini (Instagram: @federicogiannini1), published on 03/02/2019

Categories: Exhibition reviews

/ Disclaimer

Review of the exhibition 'Paul Klee. At the Origins of Art' at MuDEC in Milan from October 31, 2018 to March 3, 2019.

It was not long after the publication of his visionary essay The Spiritual in Art, that Vasily Kandinsky (Moscow, 1866 - Neuilly-sur-Seine, 1944) began to develop the idea of starting to write an almanac that would collect reproductions of the most disparate artistic creations: paintings, sculptures, drawings, engravings, tapestries, but also ethnic objects, works of art from non-European cultures, and works created by children. A heterogeneous collection that, together with the theoretical writings that would accompany it, had the declared intention of extending the existing limits of artistic expression and was at the same time a pioneering investigation of the impulses that drive human beings to make art. Kandinsky involved his younger colleague Franz Marc (Munich, 1880 - Verdun, 1916), and in concert they thought of naming the almanac Der Blaue Reiter, the blue knight: “we invented this name,” Kandinsky would later recall in his writings, “in the garden of Sindelsdorf,” the small town in Bavaria where Marc was living at the time and in which the two struck up their friendship. “We both loved blue, Marc the horses and I the riders,” Kandinsky recalled. “The name came up by mutual agreement.” The almanac that would later give its name to one of the most relevant groups of artists in twentieth-century art was published in early 1912, in a single issue (although the primary intent of the authors was different): nonetheless, it was a work that attracted significant attention, above all that of Paul Klee (Münchenbuchsee, 1879 - Muralto, 1940) who, like the artists of the Blaue Reiter, nurtured a strong and heartfelt desire to investigate the innermost, transversal, and complex origins of artistic expression.

This is the main antecedent that could constitute the premise, both narrative and theoretical, of the exhibition Paul Klee. At the Origins of Art, curated by Michele Dantini and Raffaella Resch and aimed at proposing to the public of the MuDEC - Museum of Cultures in Milan a profound and original reading of the Swiss artist’s work, considered in relation to the theoretical and iconographic processes underlying it: in other words, the exhibition questions what are the sources Klee drew on, what are the philosophical assumptions of his investigation, how his production is placed in the context of the primitivist tensions that characterized the action of many artists active at the beginning of the twentieth century (and consequently what are the distinctive features of Klee’s primitivism), what is his position in the years that saw the flourishing of the first “abstract” works of art. As a preliminary remark, it should be noted that the MuDEC exhibition is animated by a scholarly project that is the result of many years of work on the sources of Klee’s art, and that its approach focuses on them: not, therefore, an exhibition that proposes to the public a paratactic chronological scanning of his production or that develops a discourse by themes without a strong glue at the base or without new readings emerging, as often happens at exhibitions that deal with this period of art history, one of the most studied but also one on which the public’s interests are most concentrated and, consequently, on which “the offer” is broadest, although often not as profound. In contrast, Paul Klee. At the Origins of Art is a highly appreciable scholarly operation that does not even fail to be exceedingly enjoyable: and not only because the scientific project is supported by an equally valid popularization project, but also by virtue of its (obvious) consonance with the exhibition venue, which is more than ever suitable to host an event that also aims to analyze the relationship between the protagonist and ethnographic collections.

One could, moreover, place here an interesting point of departure that, at first glance, unites Klee with the artists of the Blaue Reiter. The painter, after visiting the first exhibition of the artists of the Blue Knight, entrusted his review, published in the newspaper Die Alpen, with some important considerations: “Sticking to what I believe in, and not to the momentary occasion or only to the apparent address of some result,” Klee wrote, “I would like to reassure those who have not been able to follow some predilection of a museum, and it was also a Greek. In art one can also begin anew, and this is evident, more than elsewhere, in ethnographic collections or in one’s own home, in the room reserved for children. Don’t laugh, reader! Even children know art and put a lot of wisdom into it! The more clumsy they are the more instructive examples they offer us, and they too must be preserved from corruption in time. Similar phenomena are the creations of the mentally ill, and it is by no means a vituperation to speak in such cases of puerility or insanity. If there is to be reform today, all this is to be taken very seriously, more seriously than all the picture galleries in the world.” This is most likely one of the passages that best expresses the idea of primitivism according to the artist from Münchenbuchsee.

|

| Hall of the exhibition Paul Klee. At the Origins of Art |

|

| Hall of the exhibition Paul Klee. At the Origins of Art |

|

| Hall of the exhibition Paul Klee. At the Origins of Art |

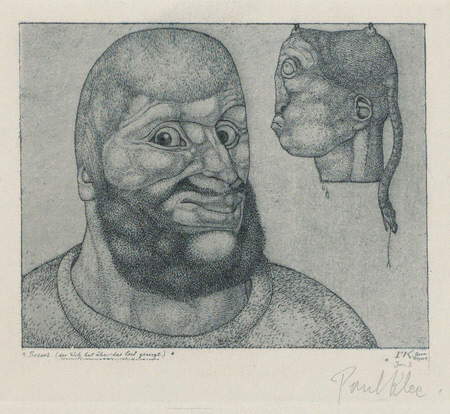

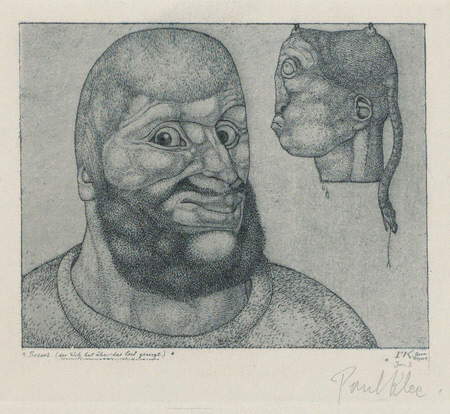

For a more complete investigation of Klee’s figurative sources, however, it is necessary to go back a few years: at the basis of his research, the exhibition places caricatures, to which an entire section, the first one, is dedicated. Masks, grotesque heads and deformed characters occupy the first room of the Milanese exhibition as an inescapable conduit between Klee and antiquity, insofar as every ancient epoch, as Jules Champfleury had noted in his treatises on caricature (which Klee knew well), always manifested a strong anti-academic verve (think of Leonardo da Vinci, Bruegel the Elder, Dürer, Bernini) that was anything but an end in itself, but was functional in extending the limits of art, in experimenting with new avenues, in investigating reality even in its most unusual and least traveled aspects. And it is also in this sense that it is necessary to read Klee’s caricatures, which certainly move from the magazines of his time (then, as now, satirical caricature was a formidable means of interpreting current events), but immediately distance themselves from such experiences to place themselves on a different plane. In the earliest caricatures (the Perseus is perhaps the best known example) the grotesque deformation of the face implies deep psychic implications (in the Perseus, according to the artist’s own description of it, “a laughter mingles with the deep lines of pain and eventually takes over,” so much so that the work’s very subtitle is The Joke Has the Upper Hand over Pain), as well as an awareness of the need to overcome a certain kind of language (Klee defined the Menacing Head as “some thought of destruction , a resigned face, on which a little demon definitely says no,” and again on this work he had this to say that “this will be the last sheet in the severe style” and that “something new will follow”), while devoted to a more intimate search for the essential will be the sheets of the following years (examples are the Masks of the 1910s that look out of Europe, or lyrical sheets such as Tierfreundschaft, which with a few pen marks, somewhere between the fantastic and the absurd, defines the friendship between a dog and a cat).

Caricature is the most natural viaticum to the mask theme, since as a boy Klee, prompted in part by his visits to the ethnographic collections of the Bern Historical Museum, used to draw grotesque heads and bizarre masks in the margins of his notes (notebooks the artist kept as a teenager are preserved). Caricatures and masks are related, from the earliest years, by decisive points of contact: “Klee,” writes Raffaella Resch in the catalog, "draws on the area of mystery and psychological terror evoked by primitive masks, where dismay and fear toward the forces of nature is accentuated, although then in his work the subterranean anguish of the human being in the face of the dimension of the unknowable is depicted with the usual critical distance and sense of humor." Some of the motifs typical of tribal arts return in Klee’s masks, such as the tendency towards geometric simplification (see, for example, the Moth Mask) or the exaggeration of certain details (the Portrait of Gaia): however, Klee, unlike other artists of his contemporaries, was not so much fascinated by theexoticism of the objects he encountered in ethnographic museums (or by their mystical or spiritual charge) as by the possibilities offered to the artist in order to scrutinize the ways in which nature is perceived and represented. For Klee, primitivism is first and foremost a source for learning that “economy” which is a necessary means of exploring the secrets of nature (“nature,” Klee wrote, “can afford to be prodigal in everything, the artist must be economical to the extreme”). And as a result, exotic arts allow one to become closer to the primal nature of the expressive act, which according to Klee, Resch stressed, “precedes all cultural conditioning, indeed, is precisely achieved by the renunciation of slavishly following any style, and constitutes a primary anthropological phenomenon, embodied in the figure of the artist.” The desire to express oneself through an artistic act would, in Klee’s vision, transcend epochs and places: for the Swiss artist, this desire responds, if anything, to a “transcendent necessity.”

What the subsequent implications of such a vision would be, is explored in the following room. Towards the mid-1910s, and more specifically starting in 1916, Klee’s works lost contact with current events, broke away from expressionist impulses, and embraced a feeling that the critic Leopold Zahn would have defined as “cosmic,” indicating with this adjective that “physical condition in which a person experiences a transcendental reality in the image of earthly reality”: a feeling that, for Zahn, finds its philosophical equivalent in mysticism. Here, then, comes the watercolor lithograph Zerstörung und Hoffnung (“Destruction and Hope”), which, with its chaotic upward-trending marks, is identified as the work that initiates the series of watercolors that Dantini calls “cosmic” and that Klee made between 1916 and 1923: the constant mystical tension that characterized the Klee of those years was also expressed through an approach to medieval religious repertories (as is also evident from the content, format and titles of some works, observe, for example, the Rocky Landscape with Palm and Fir Trees, or take note of the titling of Spielende Fische - miniaturartig, or “Fishes Playing - miniaturistic”) that culminated in the last years of World War I, “when Klee,” writes Dantini, “appears most visibly engaged, on the basis of precise prompts and readings, in reinventing early medieval miniatures, ’calligraphic delusions’ or otherwise.” In the Spielende Fische, in particular, a construction of forms that harks back to his friend Franz Marc (one of the artists Klee was closest to) is combined with the “miniature” format that would later become, to a certain extent, ingrained in his art, since it represented the format that better than any other (or perhaps only) suited his search for a painting capable of embracing the whole world, and of which, however, the painter lamented in the lecture he gave in Jena in 1924, he had found nothing but fragments: “it has occurred to me to dream of a work of vast scope embracing the entire scope of elements, of subject, of content and style. This will certainly remain a dream, but it is good to imagine from time to time this possibility, still vague. Things should not be rushed: these must come to light and grow, and if the time for that work eventually rings, so much the better! We still have to search. So far we have found fragments, not the whole.”

|

| Paul Klee, Perseus ( der Witz hat über das Leid gesiegt), “Perseus (The Joke has the upper hand over the pain)” (1904; etching, 12.6 × 14 cm; Switzerland, Private Collection, on permanent deposit at Zentrum Paul Klee, Bern) |

|

| Paul Klee, Drohendes Haupt, “Menacing Head” (1905; etching and aquatint on zinc on stiff tissue paper, 19.5 × 14.3 cm; Bern, Zentrum Paul Klee) |

|

| Paul Klee, Maske einer Zornigen, “Mask of the Angry” (1912; chalk on paper on cardboard 17.6 × 15.7, cm Bern, Zentrum Paul Klee) |

|

| Paul Klee, Tierfreundschaft, “Friendship between Animals” (1923; pen on paper on cardboard, 15.5 × 24.5 cm Private collection) |

|

| Paul Klee, Maske Motte, “Moth Mask” (1933; glue color on paper, on the back pencil drawing with glue color, 42.6 × 32 cm; Ulm, Museum Ulm - Geschenk der Freunde des Ulmer Museums) |

|

| Paul Klee, Brustbild Gaia, “Half-length Portrait of Gaia” (1939; oil on cotton imprimitura, 97 × 69 cm Switzerland, Private Collection, in permanent storage at Zentrum Paul Klee, Bern) |

|

| Paul Klee, Spielende Fische miniaturartig, “Playing Fish (miniature)” (1917; watercolor, pen and pencil on paper on cardboard 9.5 × 16 cm; Private Collection) |

Klee’s reflection on ancient sources was broader, however, and he soon took to include not only the figurative means of expression employed in the works the painter studied, but also the symbolic ones (which could nevertheless be both symbolic and figurative): “if the forms of painting in their genesis contain meaning, they bring us closer to the heart of creation,” Resch explains, “so words can bring us to an ultimate kernel of meaning in objects.” Klee, a formidable inventor of alphabets and a forerunner of post-World War II sign painting, for almost the entire span of his career continued to draw now more immediate symbols, such as pictograms resembling recognizable objects (often present is theeye, the organ that connects the outer world with the inner world: we find an eye-like symbol in Initiale A, “Initial A”) or letters of the Latin alphabet, sometimes arranged to form full words, perhaps together with symbols of invention (it happens in Album Blatt für Y, “Album Sheet for Y”), sometimes in seemingly random sequences (as in Sheet C - für Schwitters, a tribute in which the shapes of the signs almost recall those of his friend Kurt Schwitters’ Merzbau), or again give rise to complex and unexpected systems: Getrübtes (“Turbled”) is a 1934 work, painted on both sides, that invents a script in direct connection with nature (so much so that the signs are arranged on a landscape on which stands out, unfailingly, the eye that observes everything), harmonious and rhythmic. The extraordinary variety of Klee’s alphabets responds to the twofold need to account for the fact that there are many interpretations of the world (and each alphabet thus corresponds to an interpretation), but there are also many situations that remain unexpressed or have yet to occur, and the sign thus becomes a means of expressing a possibility (“anthropologist of the possible” is Raffaella Resch’s definition of the Swiss painter).

It is also necessary to point out how, in the same section, a particularly significant work, theAngel in the Making, is also exhibited: the angel, often present in Klee’s figurations, is a creature suspended between heaven and earth, and Klee’s is moreover an angel in motion (“in the making,” therefore) that to a certain extent becomes almost a metaphor for the very condition of the artist, who according to Klee is himself suspended between a perceptible world and a world that is not, or not yet: “worlds have opened and are opening up for us,” the Swiss artist wrote, “worlds that also belong to nature, but into which not all men can penetrate with a gaze, which is perhaps proper only to children, to madmen, to primitives. I mean, as it were, the realm of the unborn and the dead, the realm of what can come and would like to come, but must not come, an intermediate world. I call it an intermediate world since I feel it among the worlds perceptible outwardly to our senses and can affirm it intimately in such a way that I can project it outwardly in equivalent forms.” Klee’s intermediate world is an ever-changing environment and the artist’s eye is required to grasp its most hidden aspects, but it is still bound and anchored to reality, which is why Klee’s art will never be a totally abstract art.

This brings us to the last section of the exhibition, where Klee’s relationship with forms (or “abstraction”) is explored: However, not before visiting the room displaying ethnographic objects that may have formed the basis of the artist’s research, and the surprising environment of the “puppet theater” that Paul Klee fabricated for his son Felix to play in and that in the exhibition is “reconstructed” with an exciting three-dimensional animation (but also exhibited are some of the fifty puppets that we know Klee created for his son, using discarded materials assembled to shape the strangest characters, largely inspired by masks from northern European theaters: the crowned poet, the scarecrow ghost, the electric spirit, even the artist’s self-portrait): it should be noted, however, that the theater itself was a natural extension of Klee’s interest inchildren’s art.

Having passed that environment, here, then, is the last room: to rearrange the threads of the concept of abstraction according to Klee, it is necessary to start with Wilhelm Worringer, who in his 1907 essay Abstraktion und Einfühlung defined abstraction as a need for protection from the “terror” inherent in the outside world, from the disquiet that human beings feel about the phenomena they experience in reality: a feeling opposed to empathy, to the ability to enjoy an aesthetic experience in harmony with nature (hence the imitative drives proper to classical or Renaissance art). Abstraction is, if anything, the impulse that leads to “wrest the object from its natural context, from the unstoppable flow of existence,” the impulse to enfranchise the object “from everything in it that was dependent on life, that is, from all arbitrariness, to make it necessary and unalterable, to bring it closer to its absolute value.” And, in ancient times, it would find a correspondence in Nordic art, “inclined not to ’empathy’ (i.e., to a loving form of naturalism) but to ’transcendence’; ethical religious first and instead of erotic” (thus Dantini). Despite the fact that the artist, after reading Abstraktion und Einfühlung, had commented on it by stating that those contained in the treatise were convictions to which he had already arrived, the principles enunciated by Worringer, in Klee, become a substantial basis, notably at the moment when the painter will state that “the more frightening this world is, as today, the more abstract art is, while a happy world produces an art of the beyond.”

Abstraction, however, in Klee is not an escape from reality: if anything, it is the production of a possible reality (“all the transitory is only a comparison. What we see is a proposition, a possibility, a means. The real truth still lurks in the background. In colors we are not captivated by illumination, but by light. Light and shadow form the graphic world. More than a day shining with sunshine, slightly veiled light is rich in phenomena. Thin layer of mist just before it omits the star. Rendering it with the brush is difficult because the instant flees too quickly. It must penetrate the soul. The form must merge with the conception of the world. Simple movement seems trivial to us. The element of time must be eliminated. Yesterday and today as contemporaneity.”) Klee’s art always maintains ties to nature while inventing a grammar of the possible: at times the links are obvious and in a certain way even evocative (this is the case with some works on the theme of landscape, such as Sumpf in Gebirge, “Swamp in the Mountains,” or Helle Nacht am Strom, “Bright Night by the River,” characterized by a rapid and almost sudden movement, or from Abend im Tal, “Night in the Valley,” a polychromy that refers to the alpine landscape tradition typical of Swiss painting), in others they are less immediate but just as strong, as is the case in certain “checkerboards” of colors(Städtebild rot grün gestuft [mit der roten Kuppel], a “Cityscape in gradations of red-green [with the red dome]” broken down into many elementary fragments of different colors, as if to introduce this timeless and simultaneous dimension into the view of a city) or again in visions in which the structure and characters of an image are considered in their changing flow(Gartenrhythmus, “Garden Rhythm”).

|

| Paul Klee, Initiale A, “Initial A” (1938; pastel on jute on cardboard, 12 × 24.1 cm; Lucerne, Galerie Rosengart) |

|

| Paul Klee, Album Blatt für Y, “Dalbum sheet for Y” (1937; gouache on paper 33 × 22 cm; Bologna, Ponte Ronca di Zola Predosa, Ca la Ghironda ModernArtMuseum) |

|

| Paul Klee, Getrübtes, “Turbled (Confused),” recto (1934; tempera and charcoal on frameless canvas painted on two sides, 17.7 × 43.3 cm; Turin, Gam Galleria Civica dArte Moderna e Contemporanea) |

|

| Paul Klee, Getrübtes, verso |

|

| Paul Klee, Angel in the Making</em, “Engel im Werden” (1934; oil on canvas prepared on plywood, 51 × 51 cm; Switzerland, Private Collection, on permanent deposit at Zentrum Paul Klee, Bern) |

|

| Paul Klee’s Puppets |

|

| Klee’s theater setting |

|

| Paul Klee, Sumpf im Gebirge, “Marsh in the Mountains” (1924; oil on paper prepared in black oil on cardboard, 18.5 × 34.5 cm; Switzerland, Private Collection, in permanent storage at Zentrum Paul Klee, Bern) |

|

| Paul Klee, Helle Nacht am Strom, “Bright Night by the River” (1932; gouache and watercolor on paper on cardboard, 58.1 × 38.2 cm; Essen, Museum Folkwang) |

|

| Paul Klee, Abend im Tal, “Evening in the Valley” (1932; oil on cardboard, 33.5 × 23.3 cm; Switzerland, Private Collection, in permanent storage at Zentrum Paul Klee, Bern) |

![Paul Klee, Städtebild (rot grün gestuft) [mit der roten Kuppel], Paesaggio urbano (in gradazioni di rosso-verde) [con la cupola rossa] (1923; olio su cartone su compensato, cornice originale, 46 × 35 cm; Berna, Zentrum Paul Klee, dono di Livia Klee)

Paul Klee, Städtebild (rot grün gestuft) [mit der roten Kuppel], Paesaggio urbano (in gradazioni di rosso-verde) [con la cupola rossa] (1923; olio su cartone su compensato, cornice originale, 46 × 35 cm; Berna, Zentrum Paul Klee, dono di Livia Klee)](https://cdn.finestresullarte.info/rivista/immagini/2019/1019/paul-klee-paesaggio-urbano.JPG%0D%0A) |

| Paul Klee, Städtebild (rot grün gestuft) [mit der roten Kuppel], “Cityscape (in gradations of red-green) [with the red dome]” (1923; oil on cardboard on plywood, original frame, 46 × 35 cm; Bern, Zentrum Paul Klee, gift of Livia Klee) |

|

| Paul Klee, Gartenrhythmus, “Garden Rhythm” (1932; oil on canvas prepared on cardboard, reconstructed frame, 19.5 × 28.5 cm; Switzerland, Private Collection, in permanent storage at Zentrum Paul Klee, Bern) |

Emphasis should be placed on the fact that Paul Klee. At the Origins of Art exhibits not only some of the iconographic sources that might underlie certain of Klee’s works (it has been mentioned how an entire room is reserved for ethnic objects but it will also be worth quickly mentioning a couple of Dürer etchings, or the North African watercolors with which the painter became familiar during his trip to Tunisia, to which a small focus is devoted that has not been given here), but also historiographical sources, starting with the biography that, Klee still living, Wilhelm Hausenstein dedicated to him: the volume was published in 1921 and from it emerges the figure of an artist who is capable of probing hitherto unexplored areas and who, Dantini summarizes, “is for Hausenstein the ultimate evolutionary term of the artistic history that is coming to an end and the first term of that which is born, beyond Europe as we know it, utilitarian and materialistic.” The result, therefore, is an even more comprehensive overview, for a subtle and refined exhibition that presents the public with the fundamentals of Klee’s art in order to reconsider, with extensive and novel readings, the terms of his primitivism, and to return an image of the painter (extended also through the six dense essays in the catalog) that is responsive to his complexity.

The result, in good substance, is a review that abundantly demonstrates the basis of Klee’s famous assumption (placed, moreover, on a panel at the close of the itinerary) that art does not reproduce what is visible, but makes visible what is not. And at the same time it allows us to take a deep look at the personality of a painter who was, Dantini points out, anything but naïve, but on the contrary a fine connoisseur of the history of Western art and well inserted in the cultural debate of his time (the structure of some of his works authorizes us “to doubt the validity of any simplification,” the curator specifies) and who was, in the words of Giulio Carlo Argan, “an illustrator of ideas, and not of abstract ideas, but of the images that, rising from the depths, from the very roots of existence, are clarified in consciousness and become the motives of daily action, of the ideas, finally, that accompany life day by day and form the ’non-visible’ world in which we move.”

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools.

We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can

find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.

![Paul Klee, Städtebild (rot grün gestuft) [mit der roten Kuppel], Paesaggio urbano (in gradazioni di rosso-verde) [con la cupola rossa] (1923; olio su cartone su compensato, cornice originale, 46 × 35 cm; Berna, Zentrum Paul Klee, dono di Livia Klee)

Paul Klee, Städtebild (rot grün gestuft) [mit der roten Kuppel], Paesaggio urbano (in gradazioni di rosso-verde) [con la cupola rossa] (1923; olio su cartone su compensato, cornice originale, 46 × 35 cm; Berna, Zentrum Paul Klee, dono di Livia Klee)](https://cdn.finestresullarte.info/rivista/immagini/2019/1019/paul-klee-paesaggio-urbano.JPG%0D%0A)