A long history, that of Surrealism. Not only because of its enduring influence, nor because of the centennial celebrations underway in Italy and abroad. Referring to the chronology that welcomes visitors to the Centre Pompidou from September 4, 2024 to January 13, 2025, we are talking about almost half a century of research: from 1924 to 1969. The two dates, which demarcate the chronological path of Surréalisme, curated by Didier Ottinger and Marie Sarré, are significant in themselves, in that they affirm once and for all its longevity and, as will be seen, also as a result of this, its geographical pervasiveness and fecundity in a wide variety of artistic genres. Traditionally included in the historical avant-gardes of the early twentieth century, Surrealism shares with some of these - Futurism above all or Dada from which it descends - a decisive question that overflows from mere aesthetic and formal research conducted in the most disparate directions. Surrealism is a worldview, an approach to life that takes into account the most unpredictable paths, a philosophy. And it does so from the beginning, in its founding document: the manifesto published by André Breton, poet and first theoretician of the current, in October 1924.

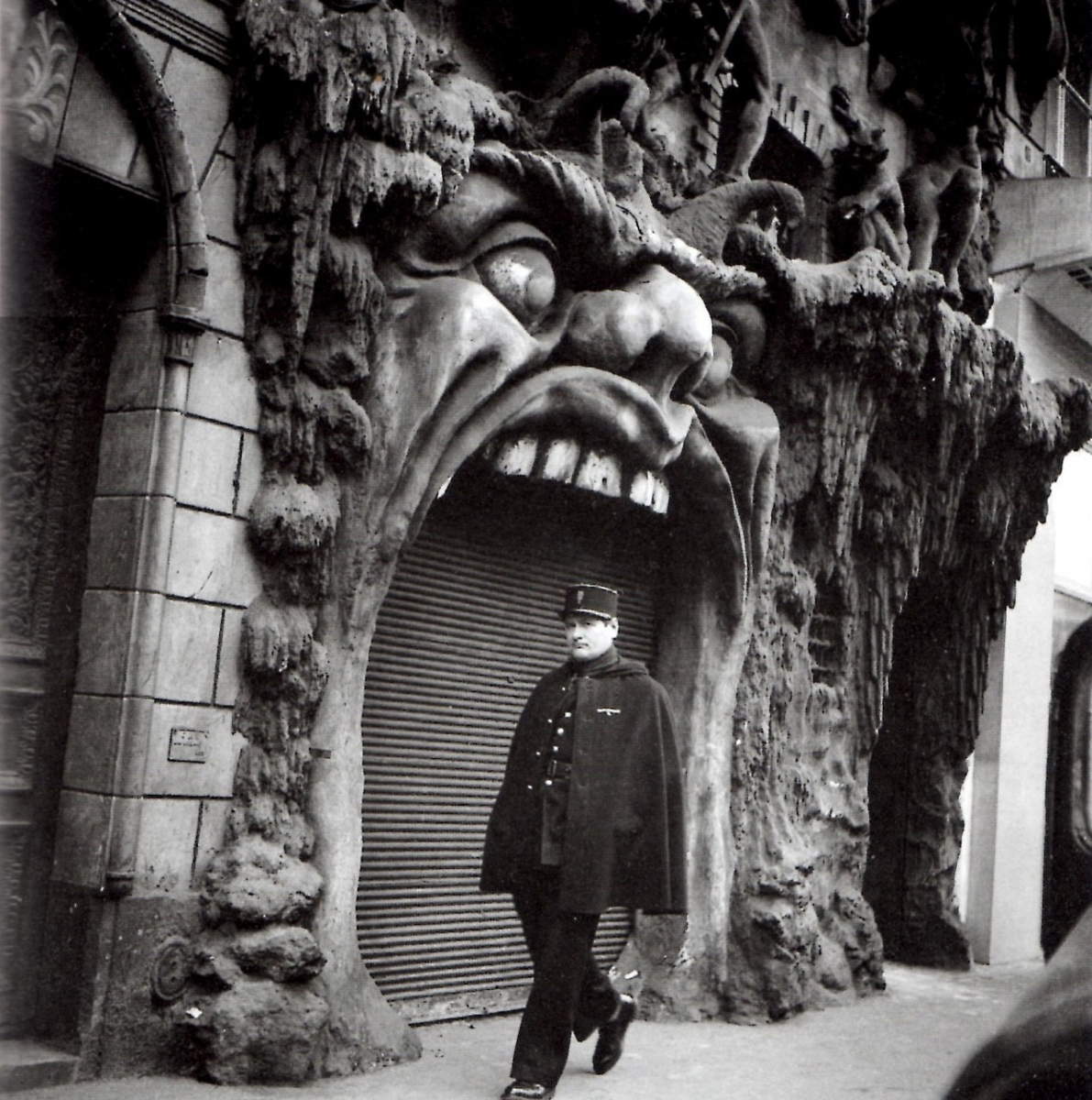

The text, which is worth rereading in its entirety on the occasion of the 2024 anniversary, is a melting pot of images, beliefs, literary, scientific and magical references. Not surprisingly, then, the visitor to the Paris exhibition encounters it within the first few minutes of the visit. Immediately after crossing the timeline, the last safe foothold before the invitation to enter the labyrinth on which the structure of the exhibition is built, the visitor passes through a monstrous portal, which one would think of as a haunted house in a playground. After all, in these terms, surrealist exhibitions were talked about in the newspapers. “Combat,” in reviewing theExposition internationale du surréalisme, reported on Sept. 26, 1947, “is something that has no name in any language and that resembles both the Tussauds Museum in London and the Neuilly festival, a caravanserai and the Muséand Grévin, to an attraction of the now defunct Luna Park and to the Cabaret du Néant and de l’Enfer, to an asylum, to Dr. Caligari’s laboratory.” The references are accurate and restore the sense of how surrealism was for the mid-twentieth-century visitor a source of monstrous visions. Among all the places evoked, the eye is caught by the Cabaret de l’Enfer, a historic Parisian nightclub with a hellish theme, whose entrance was eternalized in a well-known shot by Robert Doisneau in 1952 and earlier by Eugène Atget at least in 1900 and around 1910, before disappearing behind the facade of a supermarket. This programmed reference is thus not allegorical, but rather topographical: the entryway in the exhibition refers directly to the hellish locale that represents one of the many Surrealist sites in the city. Perhaps one of the most evocative for the 2024 anniversary. Breton owned his studio on the very fourth floor of the same building, with access from the adjacent rue Fontaine, number 42, marked today with a plaque commemorating the address as “centre du mouvement surréaliste de 1922 à 1966.” From here began as early as the late 1910s the experiments that would lead, again in this studio, to the drafting of the manifesto, considered among the most relevant writings of the twentieth century. The text originated, to tell the truth, as a spontaneous preface to the collection “Poisson soluble,” with the intention of fixing black on white some of the principles and goals of the processes of automatic writing, initiated since 1919, and would be followed by two more manifestos in 1930 and 1942.

At the entrance to the exhibition, French representatives of the movement greet visitors in a dark corridor: André Breton, Suzanne Muzard, Salvador Dalí, René Magritte, Raymond Queneau, Jean Aurenche, Marie-Berte Aurenche, Max Ernst, Pierre and Jacques Prévert, Louis Aragon, Yves Tanguy, Paul Éluard, Jacques André Boiffard and Luis Buñuel appear, impertinent and in some cases disturbing, in vintage passport photos taken at photo booths in the late 1920s. After this brief itinerary, the tour route admits into the presence of Breton’s original manuscript. Displayed in the center of the room, it is the real cult object of the occasion, shown in its entirety for the first time, thanks to a loan from Bibliothèque nationale de France. The papers speak, then. In the circular environment in which they are displayed, it is the author’s voice that animates them, thanks to the reconstruction carried out by the team from the museum’s Institut de Recherche et de Coordination Acoustique/Musique (IRCAM), through artificial intelligence and thanks to some historical recordings and the involvement of an actor. As images of faces, writings, situations, and maps flow in an evocative immersive projection, the surrealist coordinates that will guide the path between the works are provided.

First, its description is punctuated telegraphically by Breton and can also be read in printed form, under display case, in a document headed by the Bureau de Recherche Surréalistes. The body, also known as the Centrale surréaliste and described as a “romanesque auberge pour les idées inclassables et les révoltes poursuivies” by Louis Aragon, was founded a few days in advance of the publication of the manifesto. Among its first actions was the production of 16 papillons surréalistes: yellow, green and pink stickers that, following the example of a Dada action by Tristan Tzara and Paul Éluard in 1920, would help spread the Surrealist revolution in the streets, through provocative and abstruse aphorisms and, as they said, its definition: “SURRÉALISME, n.m. Automatisme psychique pur par lequel on se propose d’exprimer, soit verbalement, soit par écrit, soit de toute autre manière, le fonctionnement réel de la pensée. Dictée de la pensée, en l’absence de tout contrôle exercé par la raison, en dehors de toute préoccupation esthétique ou morale.” Verbally or in writing, by whatever means, surrealism is a psychic automatism aimed at bringing out the workings of thought, far from any aesthetic or moral concern.

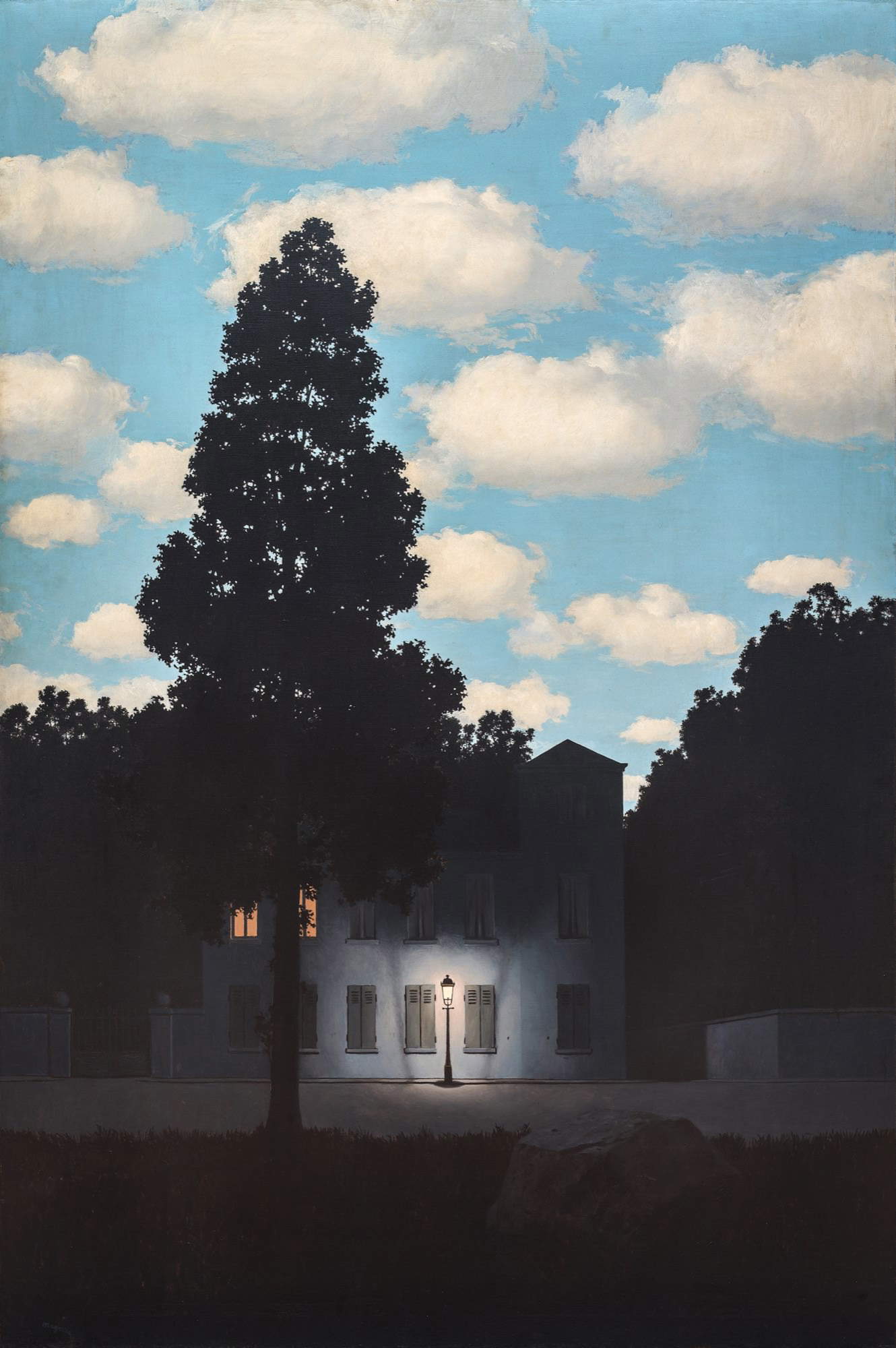

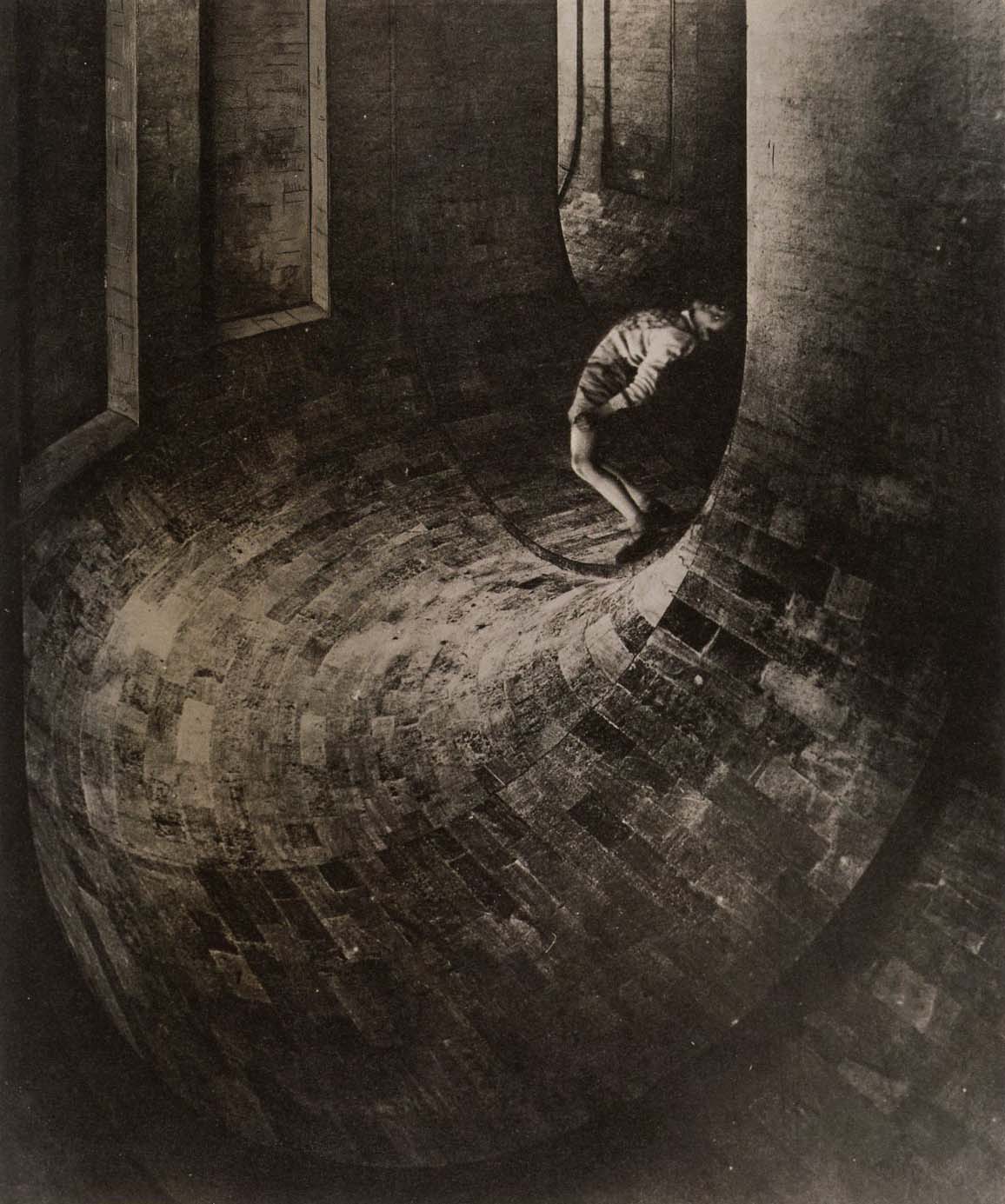

After the portal to the Inferno and after the precious manuscript, the visitor is invited to enter the labyrinth, a recurring mythological place since the Surrealist literary imagery that centers on the city of Paris (as in the novels Le Paysan de Paris by Louis Aragon, 1926; Nadja by André Breton, 1928; Dernières nuits de Paris by Philippe Soupault, 1928). The labyrinthine approach with which the curators have ordered the exhibition is then borrowed from the Surrealist exhibitions themselves, particularly the Exposition internationale du Surréalisme of 1938 (Galerie des Beaux-Arts, Paris) and 1947 (Galerie Maeght, Paris). Thirteen key words lead along the topoi of Surrealism, from early insights and early masters to literary references, political positionings and visions of the cosmos, passing through places and atmospheres: Entrée des médiums, Trajectoire du rêve, Lautréamont, Chimères, Alice, Monstres politiques, Royaume des mères, Mélusine, Forêts, Pierre philosophale, Hymnes à la nuit, Larmes d’éros, Cosmos, these are the names of the sections. The breadth of works on display includes some “textbook masterpieces”-think, for example, of canvases by Giorgio de Chirico(Le Chant d’amour, 1915), Paul Delvaux(L’Aurore, 1937), Max Ernst(La Toilette de la mariée, 1940), Salvador Dali(Reve causé par le vol d’une abeille autour d’une pomme-grenade, une seconde avant l’éveil, 1944), René Magritte(L’Empire des lumières, 1954). But the willingness to conduct research outside the best-known paths of Surrealism and to reconnect it with earlier figures and in some cases later situations also allows us to explore the work of artists less emblazoned or whom one would not expect to encounter. The itinerary is dense and swirling, the suggestions many and each attempt at synthesis complex to articulate, without leaving out pieces that evidently only united can fully represent a movement that already in the late 1930s united the research of artists from fourteen different countries.

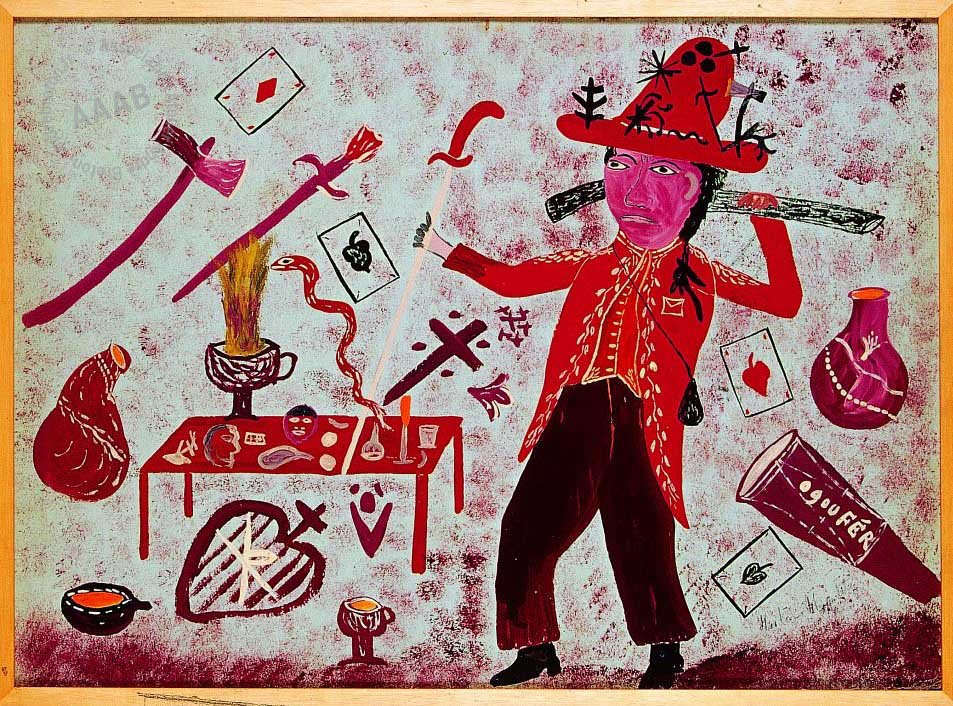

The first chapter of the exhibition, entitled Entrée des médium, citing a text published by Breton in 1922 in “Littérature,” explores the origins of Surrealism in its mediumistic dimension. Chronologically we move back as far as 1860, with a symbolist etching by Victorien Sardou, La maison de Mozart, and one of the recognized masters of the movement appears from here: the “pre-surrealist” Giorgio De Chirico and his emblematic [premonitory] Portrait of Guillaume Apollinaire (1914), in which the French poet takes on the guise of Orpheus wearing a pair of sunglasses to symbolize the ability to see the world beyond appearances. In the background, Apollinaire’s silhouette marked by a scar anticipates the one that would really appear on his face years later and following an injury. This story makes De Chirico himself a clairvoyant for the Surrealists. A similar story is that of Victor Brauner’sAutoportrait (1931), in which the artist is shown without the eye that he would lose only years later. Also by Brauner, the well-known painting Le Surréaliste (1947) is exhibited, juxtaposed with Hector Hyppolite’s Ogoun Ferraille (1947). Both works, highly symbolic, show more or less explicit references to the arcana of the Juggler and the Bagatto and to the world of tarot cards that the visitor later re-encounters along his or her tour route. Their presence, then, begins to sketch in the visitor’s mind the geographic boundaries of the movement: not only Paris, as the capital of the avant-garde, but immediately Europe, given Brauner’s Romanian origins, who would later become French by adoption, but also Latin America, given Hyppolite’s Haitian origins.

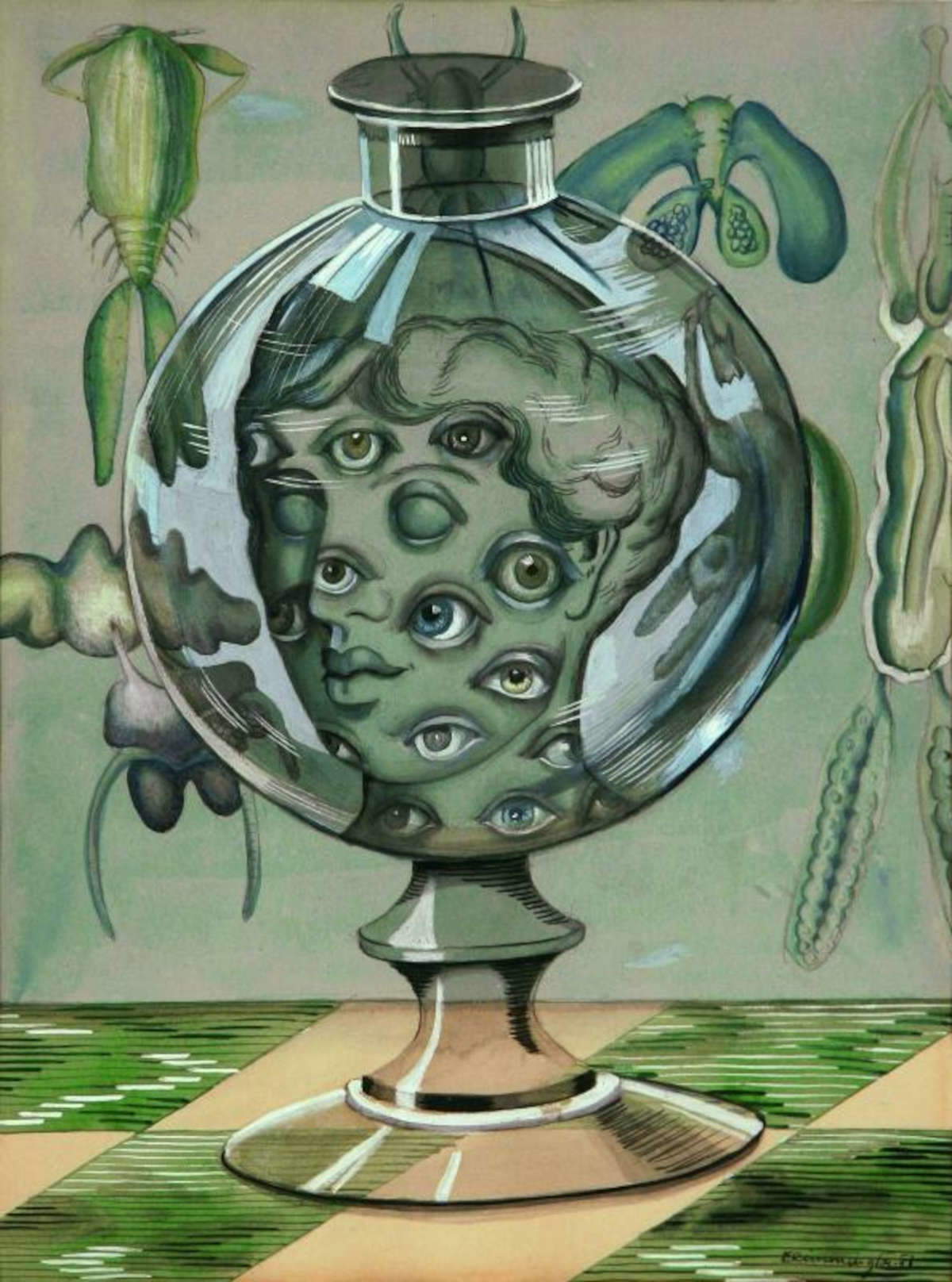

The theme of denied sight that opens to new perceptual universes also appears again in works such as Eileen Agar’s Angel of Anarchy (1936-1940) or in Edith Rimmington’s Museum (1951). The two works, a sculpture and a drawing, by the British artists, open up another question concerning the in-depth study of the history of Surrealism offered by the Pompidou: the presence, from the very beginning, of a strong female component within the group, generally less known to the general public and gradually gaining more attention thanks to exhibition projects such as Fantastic Women. Surreal Worlds from Meret Oppenheim to Frida Kahlo (Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt, 2020) or Surréalisme au Féminin? (Musée de Montmartre, 2023) and evoked from the title by the 59th Venice Biennale, which quoted a storybook by Leonora Carrington, The Milk of Dreams. On the occasion of the centenary, the Pompidou itself, thanks to Marie Sarré published Les Magiciennes. Surréalisme et alchimie au féminin. Leonora Carrington, Ithell Colquhoun, Remedios Varo (2024), which collects and partly translates into French for the first time some texts by the three artists.

Also in the text Entrée des médium, Breton writes “on sait [...] ce que, mes amis et moi, entendons par surréalisme. [...] un certain automatisme psychique, qui correspond assez bien à l’état de rêve.” In the 1924 Manifesto, too, the theme of the dream is central and also takes into account medical and psychoanalytic research just prior or contemporary to it. Breton states “I believe in the future solution of those two states, apparently so contradictory, which are the dream and reality, in a kind of absolute reality, of surreality, if one can say so. It is to its conquest that I am going, certain of not getting there but too heedless of my death not to somehow foreshadow the joys of such a possession.” This dual concept is well portrayed, almost illustrated, powerfully by Diego Rivera in Les vases communicants (1938), a poster with violent colors and a pronounced stroke, made on the occasion of Breton’s lectures at the University of Mexico. The dreamlike imagery unfolds, then, in its power through the disturbing works of Salvador Dali(Le rêve, 1931), the energetic and chaotic ones of André Masson(Dans la tour du sommeil, 1938), and the more poetic ones of Joan Miró(La sieste, 1925). Also present as a precursor is Odilon Redon’s Les yeux clos (1890). Still in the oneiric vein, the photomontages of Dora Maar(Untitled, Main et coquillage, 1934; Le simulateur, 1936) and those of Grete Stern(Sueño nº 17: ¿quién será?, 1949) ravish.

![Giorgio de Chirico, Portrait [foreboding] of Guillaume Apollinaire (1914; oil and charcoal on canvas, 81.5 x 65 cm; Paris, Centre Pompidou) Giorgio de Chirico, Portrait [foreboding] of Guillaume Apollinaire (1914; oil and charcoal on canvas, 81.5 x 65 cm; Paris, Centre Pompidou)](https://cdn.finestresullarte.info/rivista/immagini/2024/2886/giorgio-de-chirico-ritratto-premonitore.jpg)

![Dora Maar, Sans titre [Main-coquillage] (1934; photomontage, 40.1 x 28.9 cm; Paris, Centre Pompidou) Dora Maar, Sans titre [Main-coquillage] (1934; photomontage, 40.1 x 28.9 cm; Paris, Centre Pompidou)](https://cdn.finestresullarte.info/rivista/immagini/2024/2886/dora-maar-sans-titre.jpg)

If the first rooms show the best-known and most recognized aspects of Surrealism, that is, those related to surreality as a dimension of the dream, as we continue, we enter sections that certainly multiply and enrich the references of Surrealism, all of which are always flanked by a rich documentary dossier and, in a few cases, selected film pills (Hans Richter, Alfred Hitchcock,Luis Buñuel). The spontaneous juxtaposition of incongruous and disorienting images continues according to the definition of ’beauty’ given by the poet Lautréamont, pseudonym of Isidore Ducasse and inspirational figure for the Surrealists: “Beau comme la rencontre fortuite sur une table de dissection d’une machine à coudre et d’un parapluie.” Man Ray’s work (1932-33) takes its title from this same quotation, flanking a number of iconic objects, of which Dali’s Le téléphone aphrodisiaque (1938) and Wolfgang Paalen’s Nuage articulé (1937-2023) are undoubtedly the most emblematic, along with Alberto Giacometti’s sculpture/furniture Table (1933). Extending the concept of assemblage, the Surrealists come to conceive, as early as 1925, the game of cadavre exquis: some of the specimens in the exhibition recount the workings of the experience that, borrowing a procedure first applied to language, produces collective works in which individual genius is deliberately suppressed. From yet another point of view, it takes upon itself these same meanings of union and amalgamation of incongruous elements the mythological figure of the chimera, which becomes a Surrealist symbol. Dorothea Tanning’s Birthday (1942) is perhaps one of the most attention-grabbing depictions of this theme in the exhibition. Related in this, too, is the legendary figure of Melusina, dear to Breton, who gives the title to an entire section of the exhibition, in the name of a renewed union between man and nature, a pairing that lends itself to different interpretations. The forest becomes a place of panic fusion, but also a gateway to the unconscious and the beginning of a new initiatory journey. Interpreters of it include Marx Ernst(La forêt, 1927; Vision provoquée par l’aspect nocturne de la porte Saint-Denis, 1927), Wifredo Lam(Lumière de la forêt, 1942), Joseph Cornell(Owl Box, 1945-46), but also, before the Surrealists, Caspar David Friedrich(Frühschnee, 1821-1822). On the theme of the night, never mentioned in the Surrealist manifesto and yet always present in the background, all the more so in the representations of an ambivalent and obscure nature, Brassaï’s photographs(Statue du Maréchal Ney dans le brouillard, 1932; Quai de Conti, 1930-32; Jardin du Luxembourg, s.d.) that explore instead glimpses of the Parisian capital, already the backdrop of the night walk in the aforementioned Le paysan de Paris.

Literary imagery, always relevant in the formulation of the Surrealists’ visual proposals, underlies a series of works explicitly dedicated to Lewis Carroll’s The Adventures ofAlice in Wonderland (1865) or influenced by the rediscovery of the pages of the Marquis De Sade. Carroll’s character breaks the constraint of logical thought for the Surrealists and becomes almost an obsession for them and the starting point for subsequent reworkings and rereadings: lyrical and dreamy in René Magritte(Alice au pays des merveilles, 1946), nocturnal and somber in Clovis Trouille(Le rêve d’Alice dans un fauteuil, 1945), hypnotic and suggestive with respect to the world of everyday objects with Marcel Jean(Armoire surréaliste, 1941) or still social and on the female condition in Dorothea Tanning(Portrait of a Family, 1954). Love, with the eternal opposition between Eros and Thanatos, is seen as a free, revolutionary and scandalous feeling. This is demonstrated, for example, by Toyen’s erotic illustrations(Sans titre, 1930), Dali’s disturbing images(Le grand masturbateur, 1929) and Félix Labisse’s(Danaé, 1947), Mimi Parent’s objects (Maîtresse, 1996) or Hans Bellmer’s La Poupée (1935-1936).

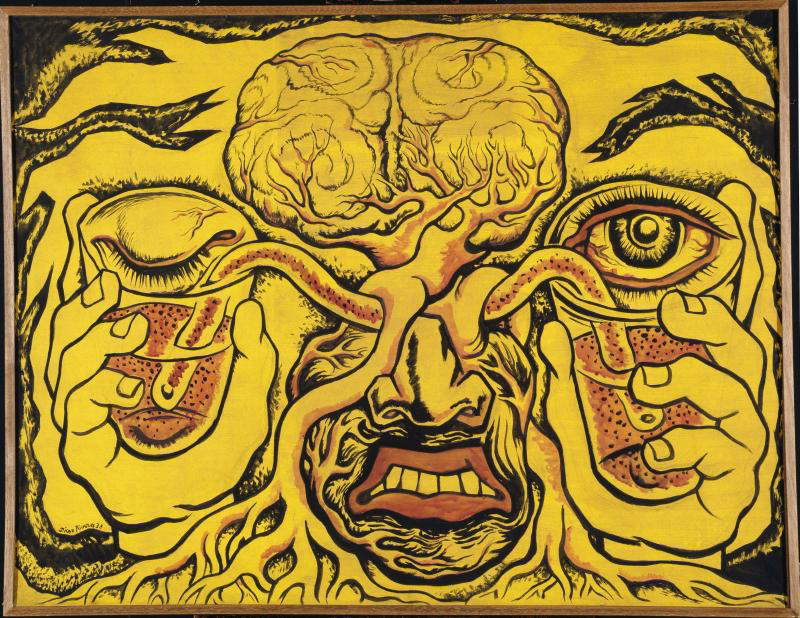

The Surrealism centennial exhibition at the Centre Pompidou is part of a traveling tour, which started at the Musées royaux des Beaux-Arts de Belgique in Brussels and will touch on the Fundación MAPFRE in Madrid, the Kunsthalle in Hamburg and the Philadelphia Museum of Art during 2025, with specific declinations for each venue. Set up on an area of more than 2,200 square meters, the in-depth tour extends outside the museum halls and takes further space in the symbolic places of surrealism and in the galleries that show what impact the movement has left on contemporary production. After all, and these are also themes that the curators wanted to emphasize on the occasion of the current anniversary, Surrealism had a significant scope in providing a possible new reading of the world and in attempting to reshape it, often in open aversion to oppressive, totalitarian and colonialist political systems. The focus on creation-related mythologies (see Yves Tanguy’s paintings, Maman, papa est blessé, 1927 or Vent, 1928; Brauner’s Fête des Mères cycle); theuniverse made of monsters, sometimes interpreted as more or less recognizable political allegories, starting with the same guiding image of the exhibition project (Max Ernst, L’ange du foyer ou le Triomphe du Surréalisme, 1937); the need to find new reconciliations between science and poetry and the attention thus directed to alchemy (Remedios Varo, Papilla estelar, 1958); the gaze that becomes wide, reaching visions of the cosmos and the desire to shape a civilization renewed, which also takes its cues from non-Western models, to reconsider and question, as in Prolégomènes à un troisième Manifeste ou non (1942), the place of man and living beings more generally.

The centenary of Surrealism at the Centre Pompidou, which is then heading for a multi-year closure, is a true re-immersion into a movement too often focused on a small number of personalities and generally traced back to a European dimension. The exhibition, which follows chronologically in the same museum other in-depth thematic(La Révolution Surréaliste, 2002; La subversion des images, 2009; Le Surréalisme et l’objet, 2013; Art et liberté, 2016) and monographic exhibitions, is accompanied by a podcast and a mighty volume that investigates and accompanies the reader both to exhibition chapters and to more pointed insights into themes crucial to Surrealism (alongside reflections on wonder, for example, the global dimension, the role of women, political vision, and the relationship between art and society) and no less relevant for today’s reader.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.