Notes on Valerio Adami. In the margins of the exhibition on the Royal Palace in Milan

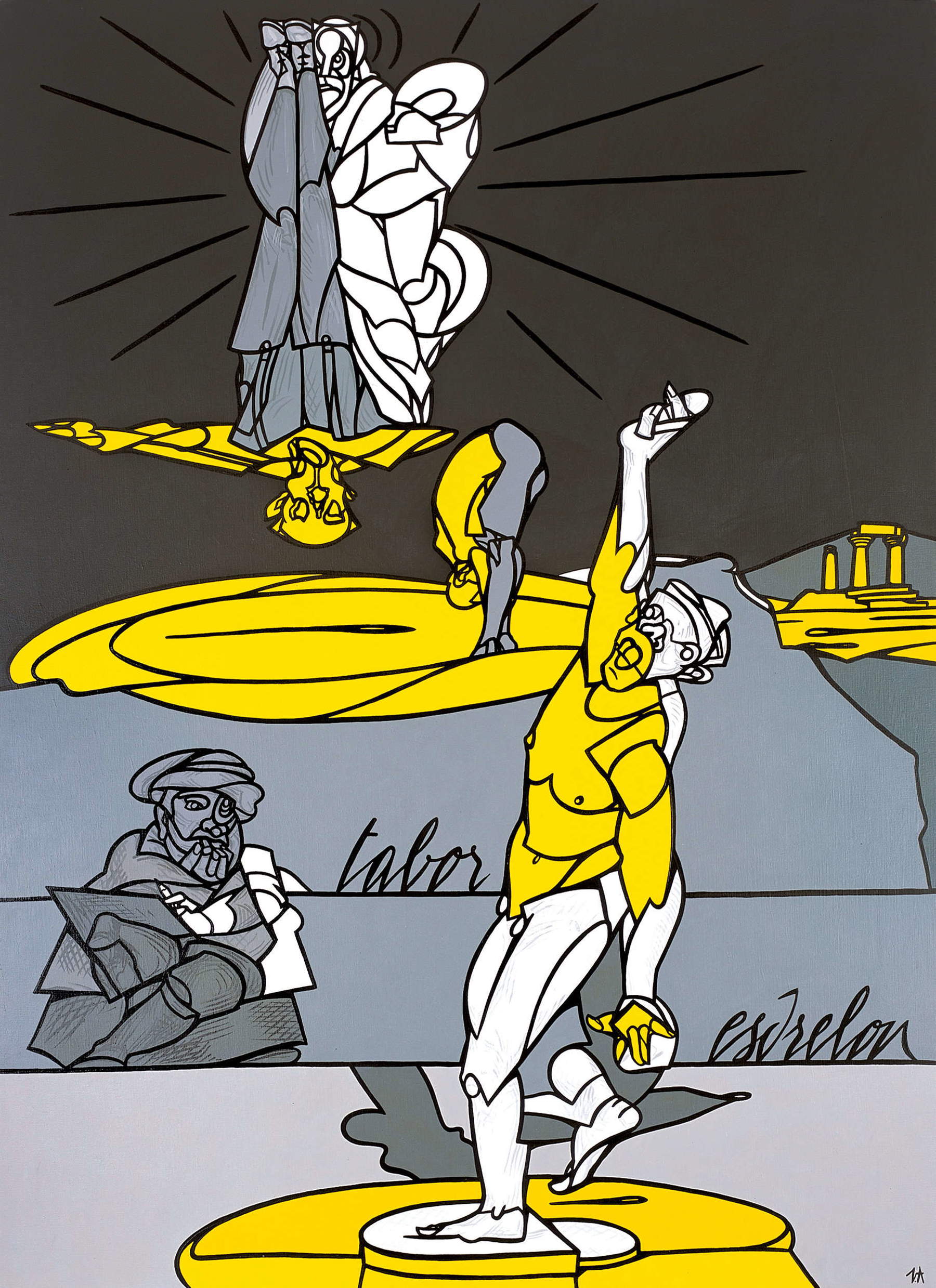

“To draw well,” Valerio Adami asserted, “one needs broad gestures, I would say the style of a tennis player... ”. On several occasions during his long career, he in fact argued for the primacy of drawing in his creative research: it is here - as attested by many of his thoughts gathered in the now unobtainable Sinopie, of which a new edition would be desirable - that the elaboration of figurative ideas is accomplished, and in which the reasons for a certain world of images surface to consciousness. “Drawing,” the artist wrote in his book, “is a way of knowing, not a way of living. The eye performs an infinite number of operations.” A few lines earlier, in another thought, he had stated that the Romantic painters “mistook drawing for shorthand,” further underscoring that mental dimension that made him, as the title given to his major retrospective at the Palazzo Reale in Milan, curated by Marco Meneguzzo and accompanied by a Skira catalog, a Painter of Ideas. There is something in these statements that harks back to Poussin, or more generally to seventeenth-century classicism and the idea of an art that has learned to govern the passions: as much as the term “surprise” is recurrent in Adami’s writings, and as much as in his writing, alongside theoretical reflection, he does not disdain the transcription of psychic associations of the Surrealist order (iconologically very useful), he does not give in to the automatic writing of the painting, but allows that first impression to be condensed in the line drawing, achieved by revisions and corrections. In fact, the dominance of drawing, in Adami, corresponds to the value of invention rather than of sign: the first spontaneous tracing, as it emerges from the works on paper, is immediately cleaned up and synthesized into a continuous line that seals the backgrounds: it has almost an impersonal value, as if it annulled the presence of the hand in favor of an image that seems to have made itself, ideal for graphic translation. His, as Meneguzzo pointed out in the Milan exhibition catalog, is in fact a drawing in which the eraser has always counted as much as the pencil, and if it does not make the sinopia of ideas that have been left out along the way disappear, it does in any case arrive at an elegant and reasoned synthesis.

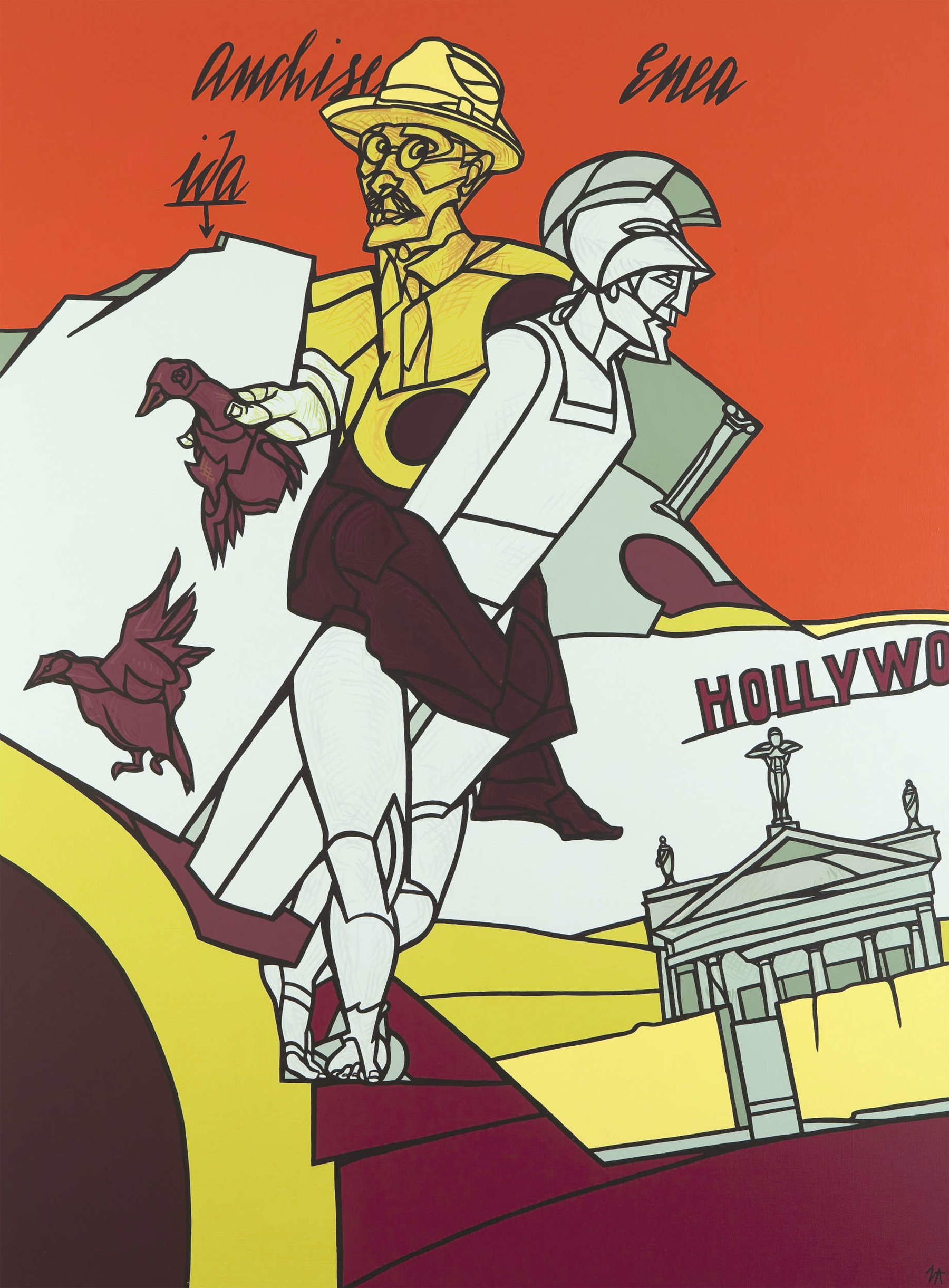

After all, as a 2015 exhibition dedicated to the artist’s most recent production recited, his work is configured over time as “ars combinatoria.” The very choice of a Latin diction perfectly suited the elegant and erudite aspect of this painting, made by a man of wide and deep readings, accustomed to self-reflection in epigrammatic form. It applies especially well to the most recent stretch of his journey, in which the style has reached a more refined sophistication of taste: the narrative has become literary, and even when it does not immediately declare its sources, it feeds on quotations and does not disdain a mysterious allegorical afflatus. It will be interesting, sooner or later, to pull the strings of an iconology of Adami’s painting, trying to bring into focus the rapid change from the more properly “pop” themes that had brought him out of his new-figuration beginnings, directing him to the graphic modes of comics, to his well-known synthesis of drawing and painting in flat colors. Only in this way will it be possible to clarify whether his was more a painting for poets or for philosophers, between Calvino and Tabucchi, Sanesi and Tadini, up to Derrida, who not surprisingly turned to him for the cover of The Truth in Painting. One may conclude, perhaps, that his painting lent itself better than others to those writers who made literature with a marked speculative attitude.

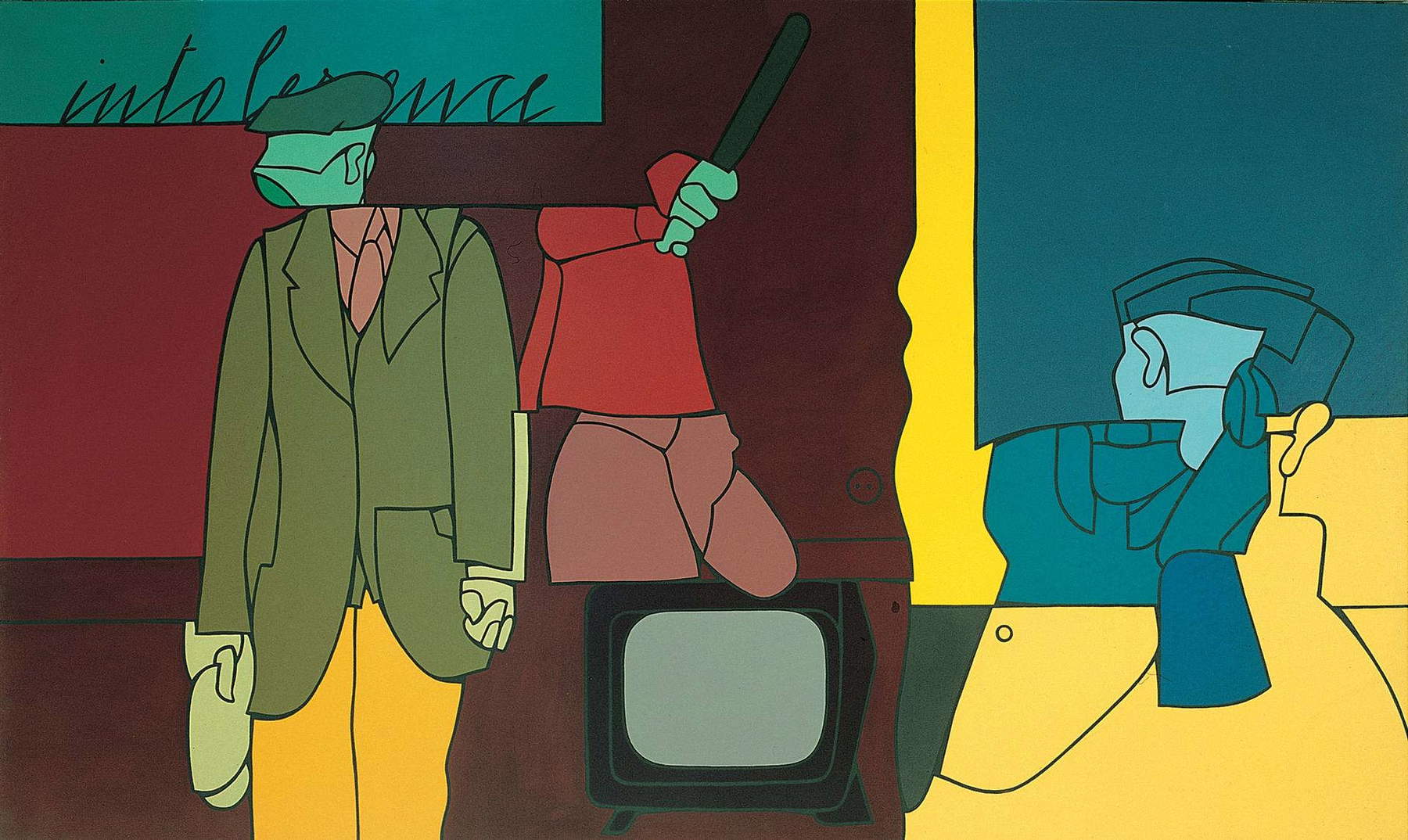

Within this painting, which remained true to itself for over fifty years with a brand of unmistakable iconicity, an internal evolution then occurred by gradual steps of refining and complicating the linear motifs of the drawing. From domestic interiors, from the pop aura of its toilets or bathtubs reduced to a few colors and timbral arrangements, or designer sofas transformed into interweaving orthogonals, the line became more sinuous and complex as the contents became narratively and symbolically more articulate. The protagonist, after the interior views, is the figure, an actor who stands out on a scene that is often rarefied or at any rate a comprimario: the moment attention is thickened on it, it is charged with symbolic meanings through attributes of more or less immediate decipherment, sometimes belonging to a shared code, sometimes pertaining to a personal and autobiographical symbolic hemisphere to be probed with more complex tools. The narrative, in fact, moves on two levels: on the one hand through the actual action staged in the foreground; on the other hand, the figure “tells” itself by means of elements that allude to its biography in a more or less obvious way (this is the case, for example, of certain allegorical portraits). In this sense, his is an art of both quotations and “combinations,” with a veiled allusion to the mental processes of constructing the picture by assembling parts.

The definitive turning point in Adami’s painting occurred precisely in the mid-1960s as interior painting: it is the modern décor, or of totally artificial places, that gives him the definitive impetus for that painting of clarity and cleanliness, of order and rigor. His relationship with drawing had already become clear with the “comics” around 1963, until the caesura marked by the great Broken Egg. After that great test it would be a matter of clarifying the relationship between drawn content and selection of elements: between figurative recognizability and pure abstract enjoyment of detail. Between these poles was the move to Paris and a plausible relationship with French “pop,” to which, however, he responded with a visionary culture, with moments of surrealism that leave one disoriented. Such is the case with the scattering of fingers with nails as sharp as canines, fatal and fierce, creeping like proliferating apparitions among the soft armchairs littered with Matisse presences, or on tables, among shower curtains and London’s public urinals. The same iconographic choice of places of marginality, deputed to clandestine encounters, is an unusual and irritating choice that Adami ennobles with an elegant color scheme, seduced perhaps by the glow of neon lights, but to which he perhaps adds an idyllic note through pastel hues, as if to emancipate a place so abject but the scene of forbidden and clandestine love affairs.

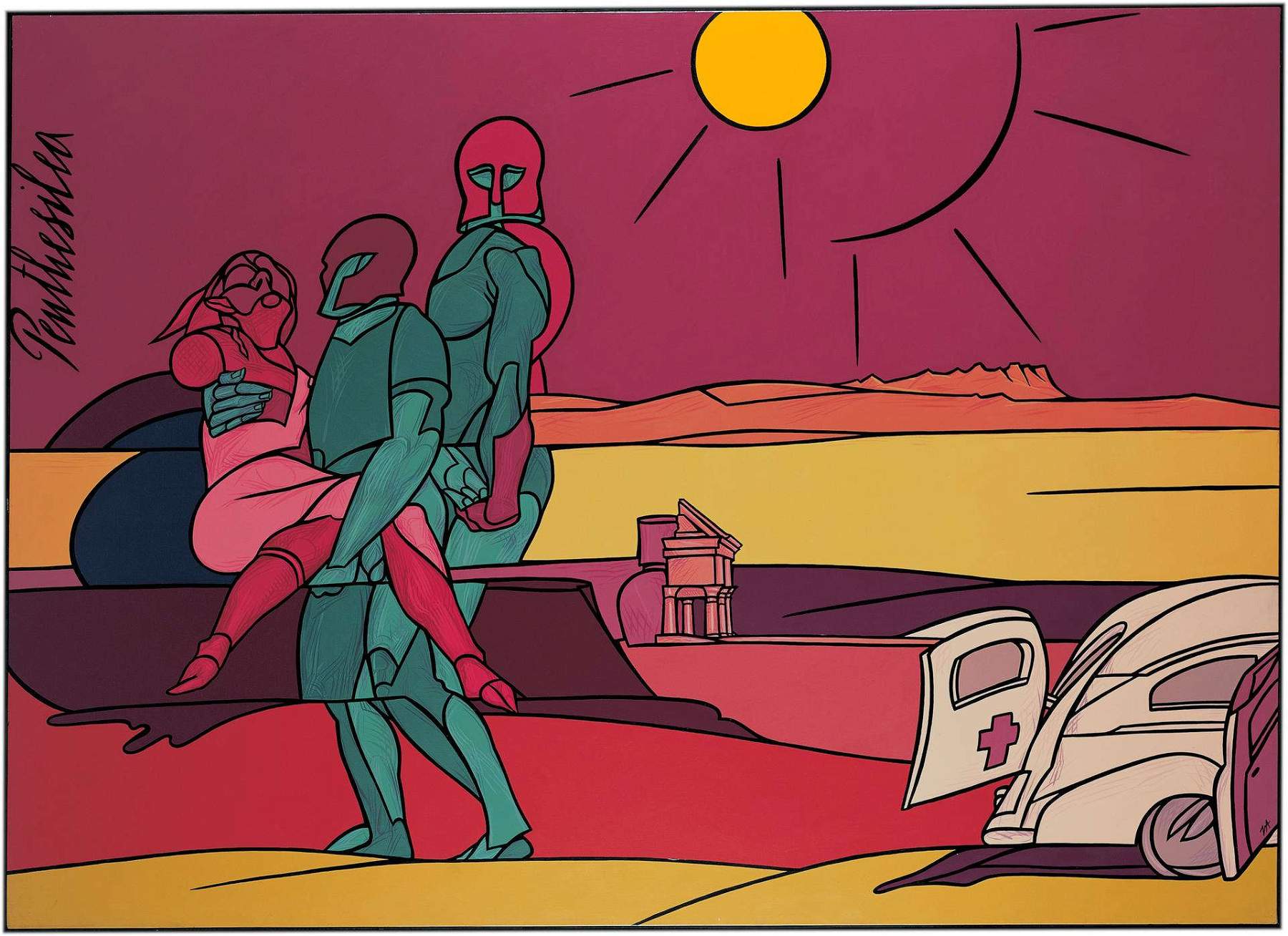

From there on, reaching the point of his best-known style, the artist merely proceeded by selection: fewer and fewer elements and larger and larger planar backgrounds, shifting the focus from concentration of content to the elegant interplay of compositional balances: He learned, in short, to handle large spaces of emptiness, necessary for a more solemn tone and to make the leap in scale to larger and larger formats, up to large murals and theatrical set design (Wagnerian to boot!). After all, he had been a pupil of Funi, and making big was a characteristic of his lesson: simplifying has always been the way to monumentalize. At that point, once he had clarified the way and the method, Adami could paint what he wanted: that mode born to restore the disorienting climate of the economic boom, of a world devoid of nature, is ready to make the leap and toward allegory, with a ductus that does not prevent him from trying his hand at the tale of invention (but more of evocation) as much as at the portrait. In fact, the compositional idea and the tale that unfolds on the canvas are all played out on thick ribbing almost like Japanese woodcut or stained glass, which close within limpid contours flat areas of color like a cloisonné enamel. Adami controls the drawing and the dialectic of lines with great care: he always knows when he has to thicken the weave to make the figures recognizable and detach them from the background, in which the fielding ramps up in its saturated chromatic compactness. Yet this should not obscure the necessity, for this line-only drawing, of the support of color: it is this, in fact, that determines the spatial breath of the composition and gives it that innate elegance. “A chaste and pure color,” the artist wrote, “is always shadowless, the tone is age, life; experiences, its extremes.” It is no coincidence that in the photographs and footage depicting the artist in the studio, the long row of cans of acrylic paints, prepared to have available all the quantities of paint needed for each application, without resorting to mixing on a palette, is striking. Adami has reduced his palette to a few colors, timbral and full, opaque, but slightly muted in tone, as if to dampen notes that are too strong, for reasons both technical and aesthetic. The use of a bright magenta, sometimes corrected with a little yellow and made opaque with a little white, is typical of his painting, and goes very well with teal, with blue, warmed up the latter by contained presences of yellow or ochre: when its presence is moderate, this color constitutes a point of attraction, a “strong color” in the painting. This is, moreover, the point at which Adami’s work has moved out of the realm of purely optical values of painting and into a different status: while the flavor and texture of the pictorial film on the canvas remains unmistakable, his work has arrived at a codification such that his images can be translated with different techniques without suffering significant trauma. Indeed, the same image can without too much effort migrate from canvas to graphics, and even to reproductions and translations in other media, without betraying its fundamental nature. Nevertheless, in front of the large paintings one realizes more than ever how much his images need the broad breath and impact of large surfaces: it is no coincidence that Adami has demonstrated great skill and skillful direction of space even on the occasions when he has come to terms with architecture.

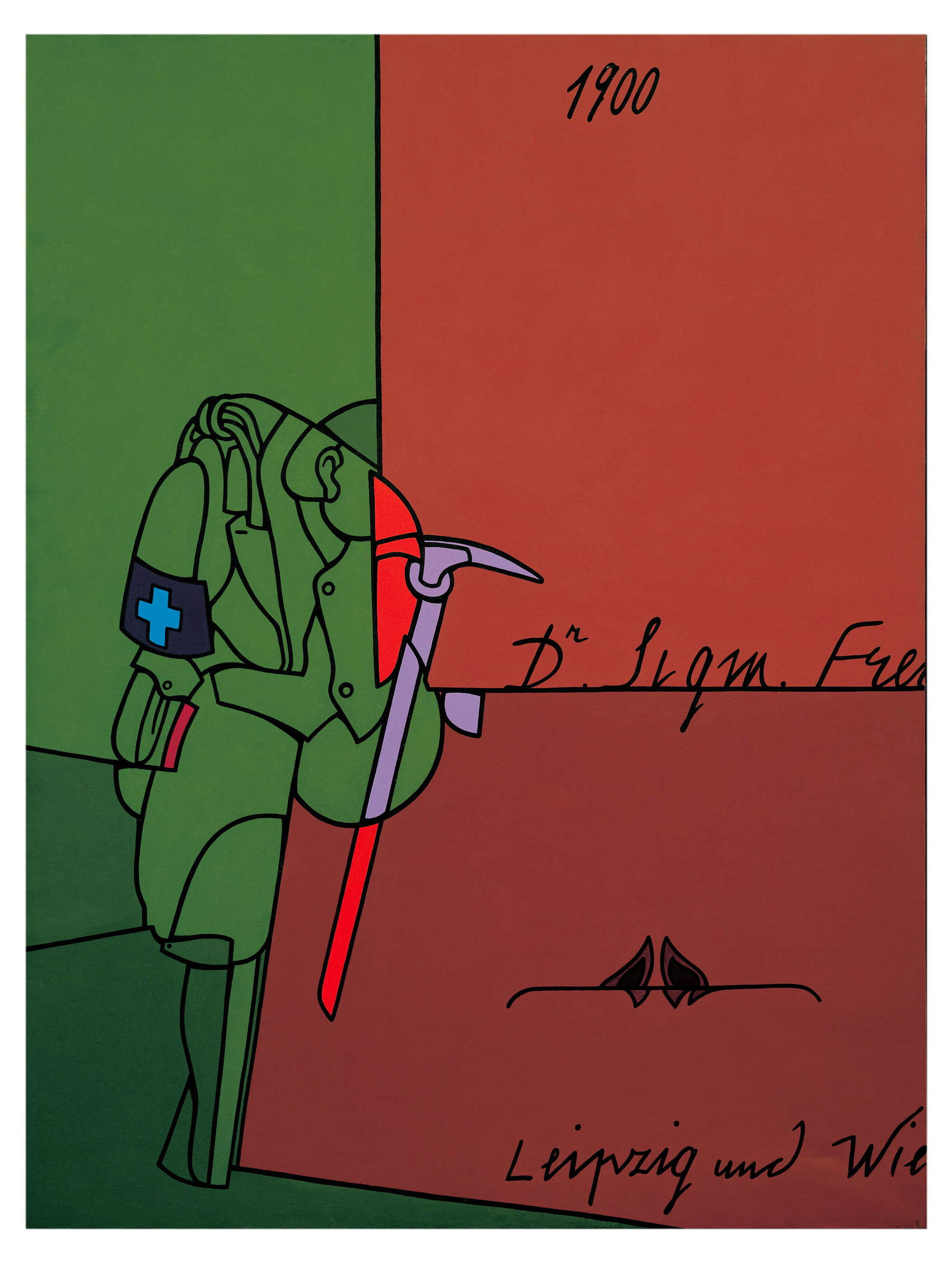

Yet, Adami never forgoes the anecdote, the small detail in the background that draws attention and captures the eye, bringing it into the heart of the painting. Indeed, not everything is indispensable to the story, but useful for compositional balance and to offer guidance to the eye, a momentary resting point in the perusal of the image. Indeed, from the very beginning it is clear to him that in synthesis one must dose and alternate between relaxed moments and others in which the plot must thicken. Ritual of 1972, in this sense, is a fitting example of that way of working by chromatic and compositional balances: a concentrated central weight that must hold up large expanses of color. In this case, it is an assemblage of interlocking forms, entangled in a web of lines clarified and distinguished by color: a Great War soldier with his Prussian helmet shod on his head, from behind, steps into a green frame, but runs into a second figure, partially covered and less distinguishable. Blocking him, however, is above all the orange-framed frame, at once a picture within a picture and an orthogonal partition of the background. Only later do we realize that the painting is actually tripartite, and that the lower portion opens a diagonal slash to another scenario, from which a portion of a compass can be glimpsed against a violet background. The relationship between the two portions is unclear, except for an unsettling short-circuit caused by their simultaneous coexistence on the canvas, or understanding them as a dreamlike sampler, to be read in tandem with a smaller painting of the same year on Doct. Sigm. Freud.

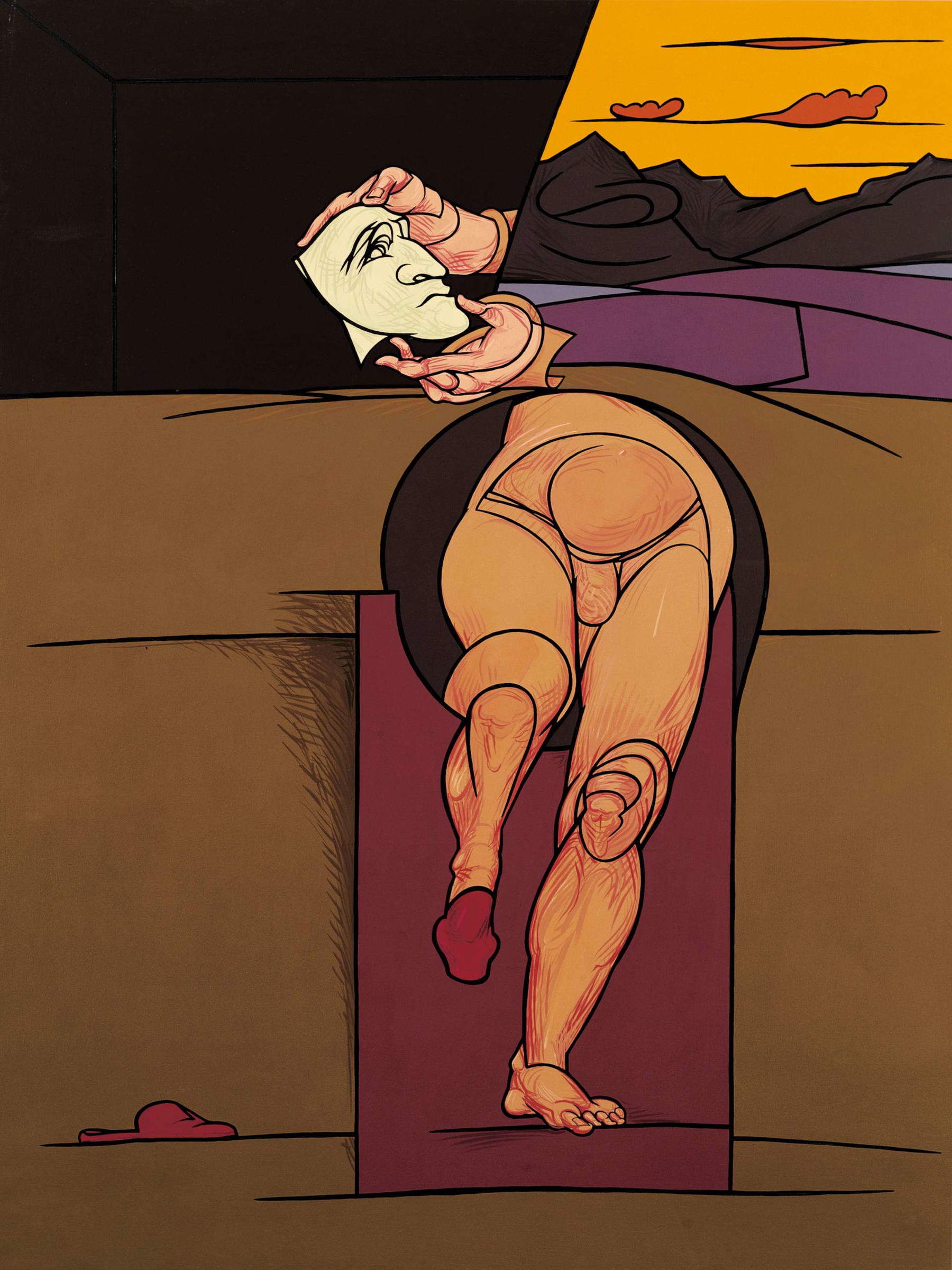

The internal evolution of his work, then, occurs by jolts of style, without tears or trauma, and is grasped over the long term. A design of interlocking parts, of interpenetrating forms held locked within one large outline in which all parts are joined and connected to each other. In the 1980s, however, the figures break away from the background and gain an autonomous space. It is here that the line becomes fluid, the profiles of the faces soften and take on folds of expression like ancient theater masks, hips with dancing profiles. A fine example of this is the 1983Self-Portrait , in which Adami’s own face is transformed into a white mask, held up by two floating hands with no body, independent of the fragment below with a glimpse of moving legs, floating in a space independent even of the sliver of mountain landscape at sunset wedged into the background, top right.

Somehow Adami has freed himself from the grid, and can work by synecdoche by summing up fragments of images and bodies, among masks, hands, torsos, medallions isolating portions of legs and lower abdomen. The painting has become a place of apparitions, where it is no longer clear whether one is witnessing a concrete scene or a dreamlike projection.

But the genuine charm of these paintings of neoclassical demeanor, in their most immediate enjoyment, lies in the fact that they do not allow themselves to be fully decrypted, and that in that halo of uncertainty they are charged with an erratic and, at bottom, deeply romantic spirit: one does not know where his approaching or receding figures are headed, and even when they stand out or giantize against recognizable monumental backgrounds, these become like dreamlike visions. But it is precisely on this threshold, which does not allow itself to be captured rationally, that a limpid and elegant feeling creeps in, deep within.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.