Topical, captivating and complete: it is with these three adjectives that I would define the anthological exhibition that Mudec - Museo delle Culture in Milan dedicates to Niki de Saint Phalle (Neuilly-sur-Seine, 1930 - San Diego, 2002), the French-American artist famous for having created that magnificent and complex park of sculptures that is the Tarot Garden in Capalbio, Tuscany. Topical because, following her art, it tackles issues that, although exploded in other eras and by merit of other generations, in the 1960s and 1970s, or on the contrary still in an embryonic stage at the dawn of the 2000s, still remain of pressing relevance, such as gender inequality, racism and environmental and global warming issues . Captivating because it is set up scenically, with bright colors on the walls differentiated to accommodate a specific moment or aspect under each hue, and with monumental sculptures that create highlights within the exhibition itinerary to highlight key concepts or figures in the artist’s production, such as The Bride on Horseback or The Three Graces. Comprehensive because the exhibition traces all of Niki de Saint Phalle’s art, from her beginnings to her latest works, while also making clear the social reflections behind her artistic evolution. It is an exhibition from which one emerges with a comprehensive portrait of Niki de Saint Phalle as a woman and artist, of her strong commitment to ante litteram feminist struggles, of her nonconformity in going against social conventions, of her great empathy for those who were victims of social and racist discrimination, of her rebellion against all forms of power and violence, of her commitment to defending rights, fighting certain prejudices and promoting a protected sexuality.

Niki de Saint Phalle was extremely modern from an ideological point of view, and this modernity poured it all into her art, into her constant desire to create, to experiment, to make people think, to innovate, to share universal values. If we stop at the appearance, her ultra-colorful, joyful and playful artistic universe might seem superficial, but in fact it is an expression of deep social and cultural reflections on being a woman, on being a mother, on being a victim of violence and an expression even of physical fragility that she addresses through art, through creation. Consider that her greatest masterpiece, which constituted her most ambitious and most complex project both to conceive and to realize, that is, the Tarot Garden in Capalbio, was intended to be a better place than the society in which she lived, where there was no form of overpowering and where all the fundamental values of living together were concentrated, thus inclusion, collaboration, participation, friendship, empathy, and the defense of rights. Atotal work of art into which to enter in order to make an initiatory journey that would lead to inner change, or rather inner peace, through overcoming the obstacles and difficulties encountered in the course of life.

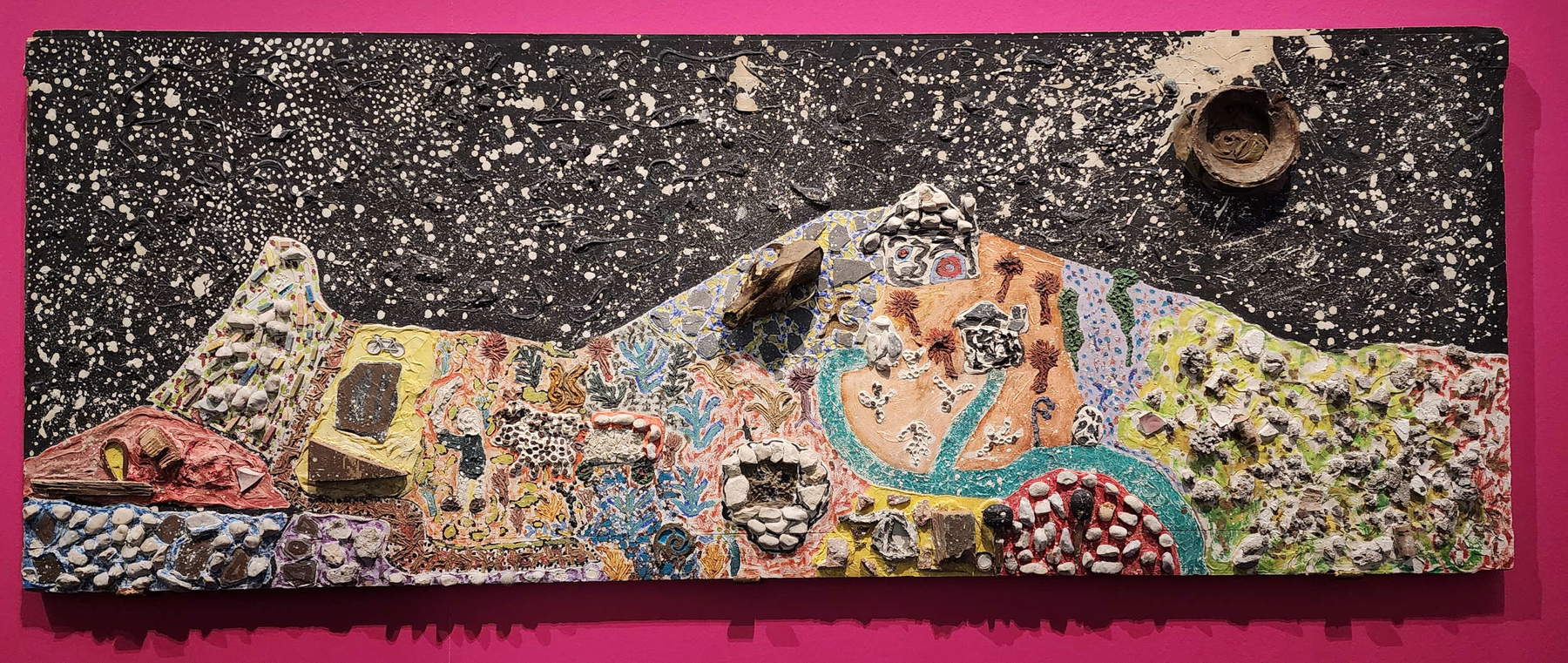

Everything said so far is well expressed and told in the exhibition at Mudec in Milan, which welcomes visitors with Nightscape, a large nocturnal landscape made by Niki in 1959 by painting on a wooden panel and gluing various objects on it, including stones and coffee beans: a collage work that is probably meant to evoke the Tuscan hills that she had met two years earlier during a summer stay in Val d’Orcia and is a work that she made as a self-taught artist. In fact, she approached art as therapy for the depression and nervous breakdowns (she was even hospitalized and subjected to electroshock) from which she began to suffer after moving in 1952 with her first husband from the United States to Paris. Placed in dialogue with Nightscape are two tempera paintings on panel, attributed to Sassetta, from the Pinacoteca Nazionale in Siena: A Castle by a Lake and A City by the Sea; the compositional scheme of the latter is similar to that of Nightscape and depicts a view of the perched village of Talamone. Saint Phalle would choose twenty years later the maritime environs of this area of Tuscany depicted by Sassetta to build his Garden: a coincidence?

In the 1960s Niki literally began to shoot painting: between 1961 and 1962 she executed a series of Shots, works that intertwined painting, sculpture, and performance. Objects were attached to a canvas and bags filled with paint were incorporated between them. These elements were then covered with an even layer of white plaster to create a neutral surface. At this point came the performance: gunshots were fired toward the canvas, striking the bags of color. When these ruptured, the paint contained within them dripped, creating fluid stains that interacted with the objects and the surface of the canvas, transforming the destructive moment into a creative gesture. The result was a work that was the visible trace of the performative process, but also represented a victimless war in a historical era of rampant violence. Clear examples of this in the exhibition are the Little Cathedral of 1962 and theTosi Altar of 1970-1972. Saint Phalle often gave these works the form of “cathedrals” or “altars,” as in doing so he manifested his struggle, his anger, against the power of the church. Along with Small Cathedral are exhibited examples of assemblage, other cathedrals and altars (of strong impact is the gilded and monstrous O.A.S. Altar, in the center of which is a large bat with its mouth open; the acronym would refer to the paramilitary insurrectionary group that opposes through terrorist actions the self-determination of Algeria). There is also Composition with Scooter (Shooting with Carbine) from 1961, a work Saint Phalle presented in a group exhibition at the Rotonda della Besana on the occasion of the tenth anniversary of Nouveau Réalisme, a group she had joined at the invitation of the art critic Pierre Restany, but most famous remains her performance in Milan’s Galleria Vittorio Emanuele (an image remembers her), where the artist shoots at a tabernacle composed of stuffed animals, sculptures of saints, madonnas and crucifixes, and the exploded red paint goes on to hit the policemen attending the performance.

The role imposed on women, by the patriarchal society, of wife, mother and bride is a tight fit for her (she is a wife at only 19 and a mother of two at only 24): through a series of dedicated works she begins to make her feminist battles against the power of men. The centerpiece of this dedicated room is the disturbing bride on horseback placed in the center of the room: a kind of corpse bride entirely covered by a white veil who is being dragged on horseback into married life. “Marriage is the death of the individual, it is the death of love. Being a bride is a kind of disguise,” he said. There are also heart-shaped assemblages with intent to denounce these social impositions. With an assemblage of 28 lithographs, she also goes so far as to criticize so-called “crocodile” mothers, including her own, those who failed to rebel against the falsehood of marriage and her husband’s betrayals in order to give the appearance that everything was fine and to keep the word out. She also criticizes herself for putting her art career before her children, and also declares that bad mothers exist, breaking a taboo. She also advocates forabortion in a lithograph with writing and drawings in her style to affirm the importance of freedom of choice for a woman. In contrast to a patriarchal type of society, she then gives birth to her Nana, which will become one of her main figures in her production and which she will continue to make throughout her life: they are colorful sculptures of buxom, joyful and dancing women, free from any stereotype of beauty, who want to claim their power, the power of women, in a new matriarchal society. Here they are dancing festively wrapped in the mirrored reflections of their own materials in the Milan exhibition route: they are The Three Graces, among the focal points of the exhibition. There is also a monumental one, twenty-eight meters long, lying spread-legged and accessible through her vagina, as seen in the image in the exhibition and in the catalog of the event in which Hon (She in Swedish), the title given to this giant Nana, was featured: it was Pontus Hultén, director of the Moderna Museet in Stockholm, who had launched the idea, which was accepted and then made concrete by Niki herself aided by the highly innovative Swiss artist and sculptor Jean Tinguely (Fribourg, 1925 - Bern, 1991), whom she met in Paris and married on her second marriage in 1971, and by Per Olof Ultvedt. Dismantled after three months, it was an immediate success with the public, not least because inside visitors could find an amusement park, a planetarium, an exhibition of fake paintings, a cinema and a milk bar. And he also made a black series out of it, to stand up for the civil rights of African Americans and to denounce a racist society. Significant, in addition to the clenched fist hanging on the wall to signify Black power, is The Lady sings the Blues from 1965, a work depicting the amputated body of a black woman to denounce how that social body was marginalized.

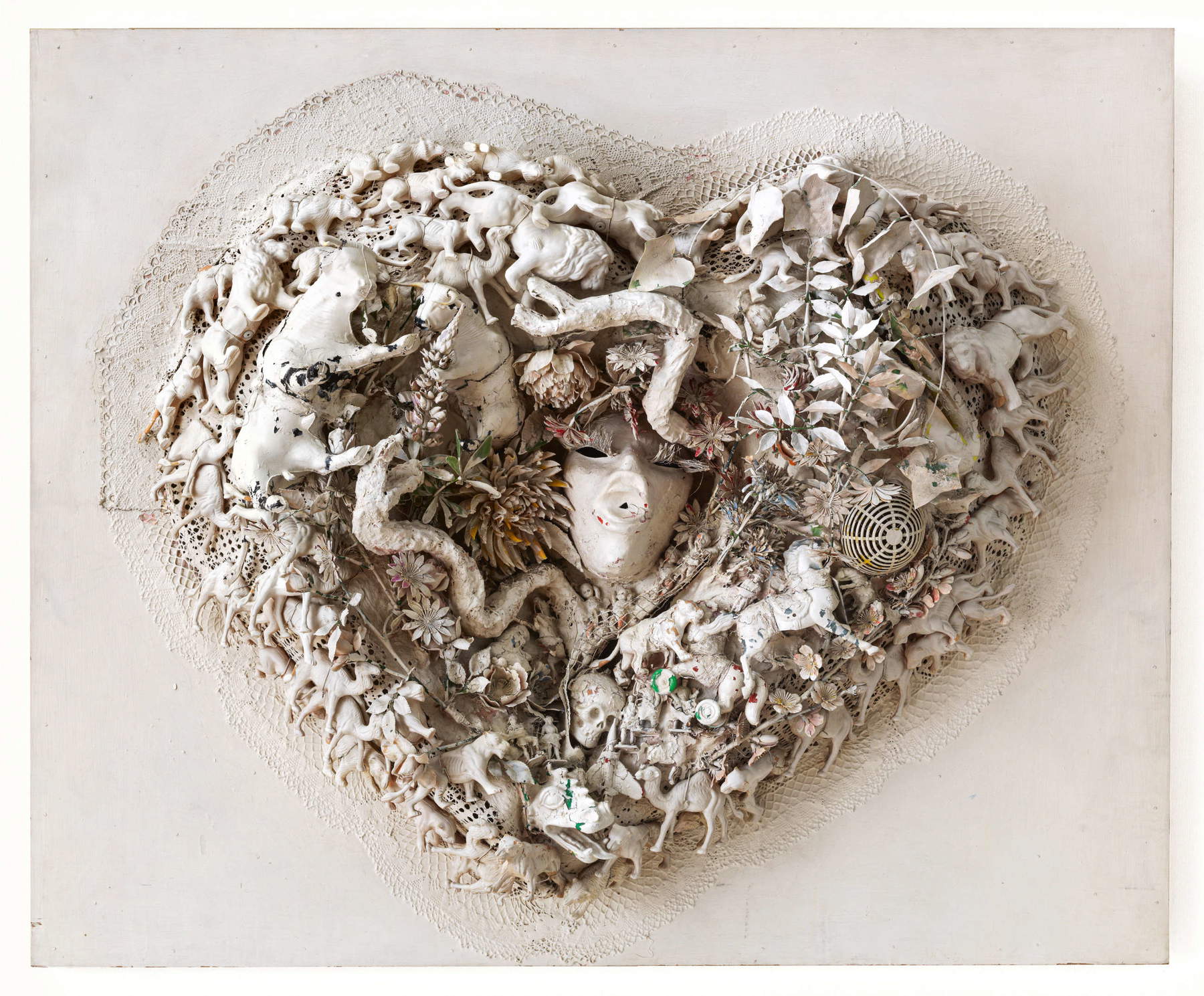

Continuing on, the visitor is welcomed, through lithographs and resin models, into the creative world of the Tarot Garden, the sculpture park that Niki de Saint Phalle began to build in 1978 in Garavicchio, on land donated to her by the Caracciolo brothers, and which was inspired by Barcelona’s Parc Güell and Bomarzo’s Sacro Bosco. Twenty-two sculptures inspired by the major arcana of the Tarot, created with the help of Jean Tinguely with steel structures covered in fired and glazed ceramics and bits of mirror arranged in mosaic patterns. The construction lasted twenty years, and Niki lived for a long time inside one of the park’s monumental sculptures, that of theEmpress, where she had created a real apartment.

The next section testifies to the artist’s commitment to information and thus prevention aboutAIDS, which in those years was a real scourge in society. Niki’s intent is to overturn the moralizing discourse about the disease and sexuality in a society that judged and marginalized people with the disease. Her contribution is the book AIDS: You Can’t Catch It Holding Hands, featured in the exhibition, written in 1986 to explain to people what it is, how to protect themselves and how they can help those with the disease; the book was distributed in 1990 to all French high schools, also anticipating the launch of famous campaigns on the subject. In the center of the room, on the other hand, one notices several Obelisks, works that the artist creates to invite protected sex and that for this reason resemble large, colorful condoms. Another delicate section is the next one in which a film and a book are the protagonists: these are Daddy, a 1973 film directed together with Peter Whitehead in which Niki makes explicit the father’s dominance over both daughter and wife and which ends with the symbolic shooting to death of the father figure, and Mon Secret, the book written by the artist in 1994 in which she reveals to her daughter the abuse she suffered at the hands of her father when she was just eleven years old. A book that has a strong therapeutic and saving power for her, due precisely to the act of writing, almost like her relationship with the figure of the snake (among the most recurrent elements in her art) that is both a symbol of sin and renewal.

The exhibition concludes with a very scenic room at the center of which are placed three tall totems: the Bird’s Head Totem, the Cat’s Head Totem and the Kingfisher Totem, which date back to 2000; however, what catches the eye first is a large skull covered with mirrors. Why these elements so far never encountered in Niki de Saint Phalle’s production? In 1993, the artist moved from Paris to San Diego, America, on the advice of doctors, and in this context she approached Mexican spirituality, discovering and delving into the myths of the native peoples who lived in Southern California, in which the concept of fertility and the relationship with the Earth was central (a 2001 lithograph is also exhibited in this room where Saint Phalle deals with the issue of global warming, today a topic of close urgency). From this new influence, he decided to create another sculpture park, Queen Califia’s Magical Circle, his last major project: the park is dedicated to Queen Califia, the mythical founder of California who led a group of warrior women. Animal-shaped totems surround the queen, symbolizing Mesoamerican cosmogony , and the wall surrounding the park is shaped like a snake. Skulls also derive from the influence of the Mesoamerican world, in this case, however, related to death, which in Mexican culture does not instill fear and awe, but on the contrary is a positive moment, to be celebrated. For Niki, representing a skull glittering with mirrors is a way to deal with advancing age, to exorcise her fears through art. It is an approach she has always had throughout her career, ever since she approached the art world as a self-taught artist to overcome depression and nervous breakdowns; for her, art has always had a therapeutic and consoling power.

An exhibition had already been dedicated to Niki de Saint Phalle in the summer of 2021, in Tuscany, in two venues in the village of Capalbio, not far therefore from her Masterpiece Garden (a visit to the exhibition event is inevitable). Now the same curator, Lucia Pesapane, has brought to the halls of Mudec in Milan the fascinating tale of this woman and artist, creating an anthological retrospective thatpays homage to all her art in dialogue with the introspective aspect, thus with her human and committed side, which as far as I remember was not placed so much attention in the Tuscan exhibition, as well as the setting that was not as high-impact as the current one. I forgot: a visit to the Tarot Garden is highly suggested as soon as the sculpture park reopens to the public, from March to October.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.