“Turner should come to Rome [...]. Here his genius would find bread for his teeth.” The consideration was expressed by Sir Thomas Lawrence, an English painter who was residing in Italy at the time, and who in a letter of July 1819 confided to Joseph Farington his wish for their young colleague. And William Turner’s wish was to visit Italy. He dreamed of its light, its wonders, its people. Probably since he was a child, the son of a London barber who had a wealthy clientele of artists, intellectuals and nobles who used to travel and on their return to England would bring back tales that are sure to have fueled young William’s imagination. This is not pure suggestion: we know of a drawing, done when he was a teenager, that reproduces the 16th-century porch of the ancient church of St. Leonard’s in Sunningwell, an Oxfordshire village where he had gone to live, in the home of an uncle of his. Other architectural drawings from the same period, depicting buildings in nearby Oxford, are the most vivid evidence of Turner’s early interests. Unfortunately, he would not succeed in realizing his dream until the age of forty-four. That was precisely in 1819, the Napoleonic wars having ended, which had always been the main reason for his renunciation of his descent into Italy. That of 1819 would be his third trip ever: only twice had he left England. The first was in 1802, when he actually got to touch Italian soil as well: from London he arrived in Paris, then moved on to Lyon, Grenoble, Geneva, a stop in Chamonix and then crossed the Alps, stopping in Courmayeur and Aosta and later taking the Great St. Bernard route in the direction of Martigny, then on to Thun, Interlaken, Brienz, Lucerne, Zurich, Schaffhausen, Basel and the return to England. A journey that lasted three months. In 1817 he stopped instead in late summer between Belgium, Germany and Holland: a month spent between Cologne, Koblenz, Mainz, Rotterdam, The Hague, Amsterdam and Dordrecht. In August 1819, finally, the opportunity to descend on Italy.

The first city he saw was Turin, and this year Turin is dedicating an exhibition to the English painter’s trip. Turner. Landscapes of Mythology, which the Reggia di Venaria Reale is organizing in collaboration with the Tate in London until Jan. 28, 2024, curated by Anne Lyles, traces the stages of that journey, but with an unusual slant. In fact, this is not the first time that an exhibition has been dedicated to Turner’s two trips to Italy (the second between 1828 and 1829, if we exclude the episodes on Lake Como in 1842 and 1843): already in 2008, in Ferrara, the rooms of the Palazzo dei Diamanti welcomed Turner and Italy, a more extensive review than the one in Turin, and aimed at reconstructing in detail the Italian sojourns of the great English Romantic, also examining the experiences of his precursors. At the Venaria Reale, it was decided to build a focus dedicated to the ideas that Turner developed in Italy, and in particular to the fascination that classical mythology ended up exerting on him, through an itinerary of about forty works, including drawings, watercolors and large paintings on canvas, all from the Tate.

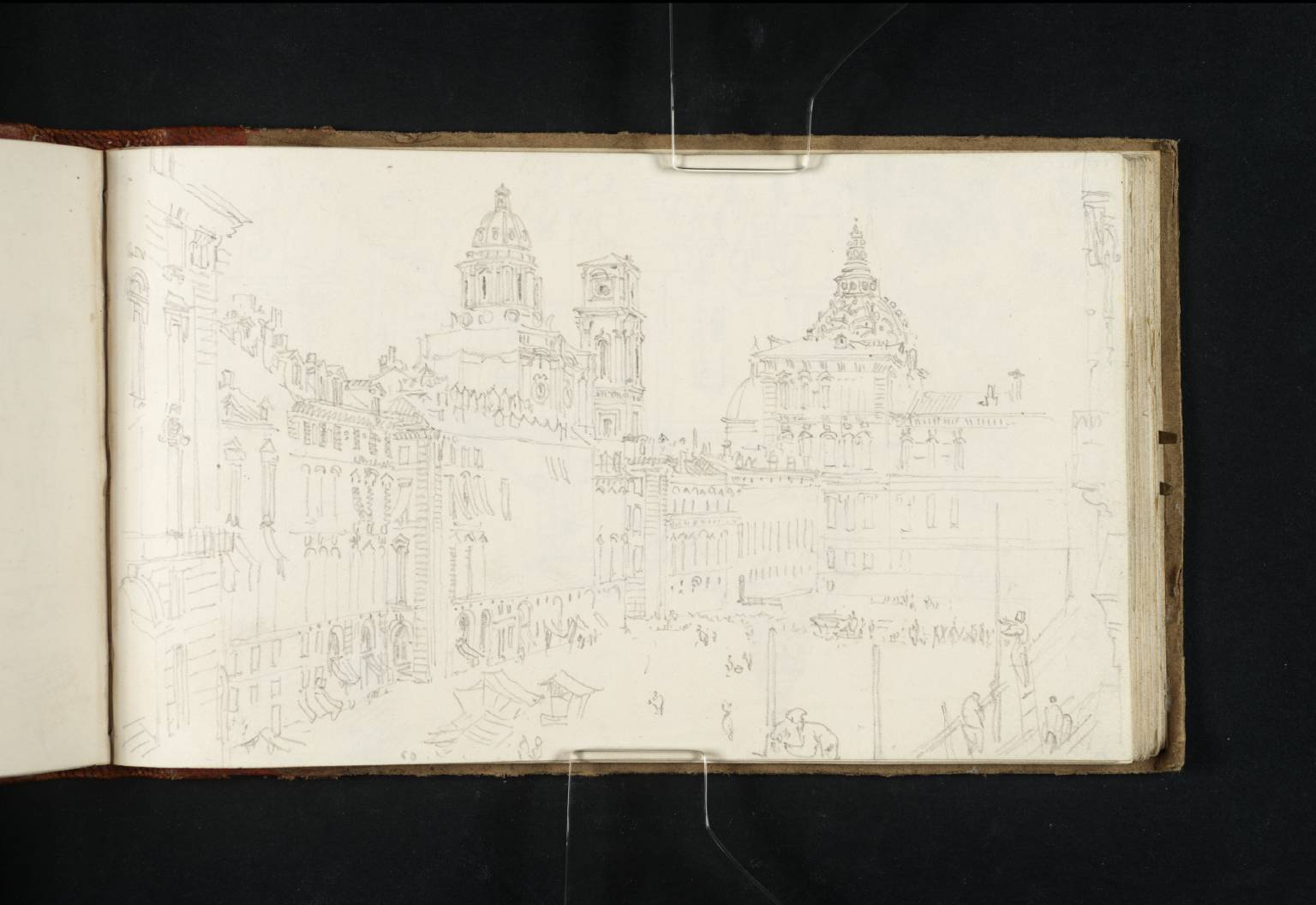

Who was the Turner who stayed in Italy? Understanding motivations and modes of travel helps to immerse oneself in the tour itinerary. And Turner was, essentially, a modern artist-traveler. Art historian Andrew Wilton, in his 1982 book devoted precisely to Turner’s sojourns on the continent, noted that the artist traveled in substantial isolation: “the season of the topographical and antiquarian artists who traveled with their wealthy patrons making drawings as souvenirs or as archaeological records had virtually ended, and when Turner declined the Earl of Elgin’s invitation to accompany him as an official artist on his expedition to Athens in 1799, he lost his only opportunity to visit Greece, and renounced forever that eighteenth-century relationship between artist and patron.” Turner almost always traveled alone, and was thus a seasoned traveler, aware of the risks of travel, but always eager to maintain his privacy, probably to avoid distractions, to grasp in the most judicious manner the suggestions that travel offered him and that he punctually recorded in his notebooks of drawings, but also in the letters he sent to friends and colleagues. Missives have also remained in which Turner gives an account of incidents that happened to him while traveling: for example, in January 1820, as he departed from Turin for London, on the Moncenisio road the carriage in which he was traveling overturned, the occupants were forced to climb out of the windows because the doors were frozen, there was also a fight between the coachman and a cantoner, with the result that the driver was immediately put in jail and Turner’s group had to continue on foot, in the snow, to the village of Lanslebourg. Inconveniences not so uncommon on long journeys in the early 19th century. It should also be considered that Turner played a pioneering role: before him, only John Robert Cozens, Richard Wilson and a few other artists had produced views of Italy (if one makes the obvious exception of Rome, which was instead, as one can imagine, a very popular destination). In front of his eyes an almost entirely unexplored world opened up, that “Terra Pictura” of which he had only heard stories or which he had seen in the landscapes of Poussin and Lorrain, his main points of reference, opened up an opportunity to reread the mythological landscapes of the great French artists of the seventeenth century according to his own romantic sensibility. That is why he had set out with him, carrying a good number of notebooks to fill with quick pencil sketches, whatever the conditions, even while traveling by carriage: we are left with twenty notebooks containing the drawings sketched by the artist during his journey.

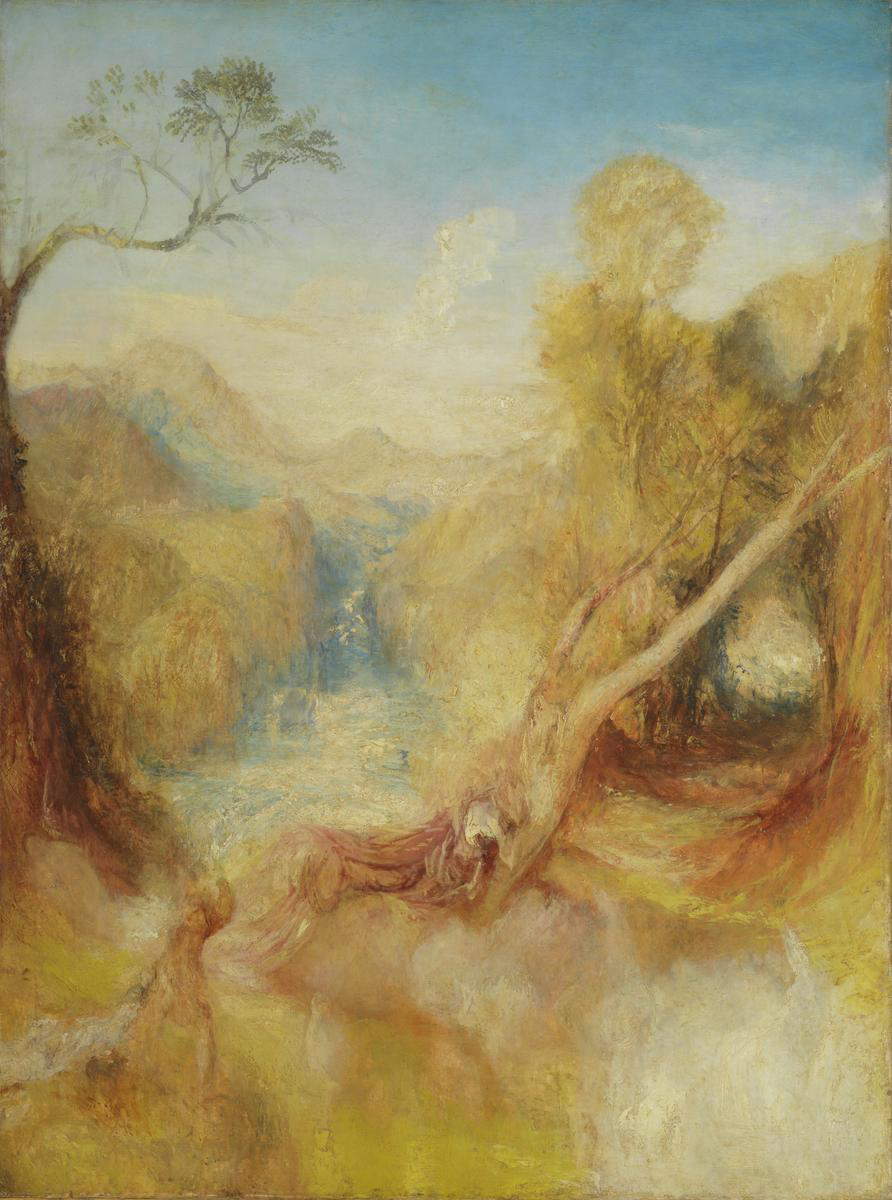

The tour begins by providing a context, with some works by Wilson and Cozens functional to illustrate the background of Turner’s journey. Cozens is known to have been the first artist to leave a rich notebook of drawings in which nearly all the landscapes he touched on his way to Italy are noted, but this is not his only legacy: on display at the Venaria is, for example, a watercolor with a view of Lake Albano (one can recognize, in the distance, the skyline of Castelgandolfo), tinged with melancholy, and tending to offer not so much a realistic view as, if anything, an idea of the uncultivated and wild nature of the Italian countryside. Next door, on the other hand, here is Lake Avernus, with the island of Capri in the background, by Richard Wilson, another artist who traveled to Italy, like Cozens, in the mid-18th century: his landscape is one evoked by Virgil’sAeneid. A watercolor by Turner, also depicting Lake Albano, is the first work by the Romantic painter that the public encounters along the way, set against the works of Cozens and Wilson to demonstrate, we read in the panels, how Turner continued to employ the same compositional methods as his predecessors (“compositions with clear perspective lines with trees as a backdrop and using soft, evocative lighting effects to reproduce morning or evening light,” mindful of Lorrain’s lazione), as well as their lighting effects. We get into the heart of the exhibition with the next two rooms, in which a summary is given of the stages of Turner’s journey, which descends in Italy from Moncenisio, stops in Turin, visits Milan and stays on Lake Maggiore on Lake Como, then goes to Venice, then leaves again for Rome and its surroundings (Tivoli, Lake Nemi, Lake Albano), to finally reach Naples, from which he moves on to visit the immediate surroundings (Paestum, Lake Avernus and Cumae) and departfinally to Turin to return to England. The heart of the two rooms, however, are the works devoted to the myth of Apollo: standing out in the center of the room is a painting recounting the story of Apollo and Python, the god of the arts who annihilates the fearsome dragon who guarded the Oracle of Delphi and who had persecuted Latona, Apollo’s mother. The work predates the trip to Italy, since it dates from 1811 (it was exhibited that year at the Royal Academy): it is an imaginary struggle, set in a fantasy landscape, and animated by the intent to provide a symbolic representation of the battle between good and evil, made evident by the contrast between Apollo’s young, naked, lusty body bathed in a golden, angelic glow and the now vanquished serpent that instead slithers in darkness. In the same room is one of Turner’s masterpieces, Baia with Apollo and the Sibyl, painted in 1823, thus executed four years after his sojourn in the places depicted: the artist painted essentially from memory, drawing not only on his Italian notebooks but also on memories of his trip to Italy, eager to return there (Turner exhibited the work at the Royal Academy in 1823, introducing it, in the catalog, with the phrase “Take me to the sunny shore of Baia”). The mythological theme (the Sibyl asking the god Apollo to live as long as the grains of sand she holds in her hand, but forgetting to ask him for eternal youth as well) is almost a pretext for painting a view of the Bay of Naples at once real and imagined, two towering pine trees and the ruins of the clearly recognizable temple of Venus at Baia providing a precise setting for the scene, with the remains of the ancient city, the harbor in the background and the sea in the distance that, as is often the case in Turner’s paintings, appear veiled, blurred by a caliginous veil that projects the landscape into the dimension of dream. Quotations also appear in the work that further refer to myth: the rabbit symbolizing Venus, the snake that is symbolic of evil but linked to the myth of Apollo and Python, the dry branches that refer to the fate of the Sibyl.

TheAeneid recalled by Wilson’s painting in the opening becomes a source of inspiration for Turner as well: the fourth and fifth rooms of the Venaria exhibition are intended to show how the artist was familiar with the Virgilian poem and had been fascinated, in particular, by Book IV, in which Virgil narrates the love story between Aeneas and the Carthaginian queen Dido, later abandoned by the hero. The exhibition revives the hypothesis, already suggested in the past, that interest in this theme may have provided Turner with a motif for comparison with contemporaneity: the rivalry between Carthage and Rome was a kind of allegory of the wars Napoleon had fought in Europe. A sketch directly inspired by Lorrain’s landscapes(Port Scene in the manner of Claude: Study for “Dido Directing the Equipment of the Fleet”), executed with a view to a painting that the artist was to exhibit at the Royal Academy in 1828 (it was not brought to Turin for conservation reasons), and close by is an engraving taken from the painting with Dido building Carthage, kept at the National Gallery in London, an 1817 work that may have a connection to the Napoleon affair (Turner, wrote James Hamilton, curator of the 2008 Ferrara exhibition, seems to suggest ironically and polemically “that empires come into being through hard work, cooperation, and the persistence of memory that is perpetuated from day to day, from dawn to dawn”).

A focus on the figure of Venus also provides an opportunity to explore the reception of Turner’s works in Italy at the time the painter was in Rome. Between 1828 and 1829, the English painter returned to our country for the second time, but he chose a different itinerary: he passed from Nice to move to Liguria, and was therefore in Genoa, then Pisa and from there to Florence. He then moved on to Rome where he spent three months, between the end of 1828 and the beginning of 1829, after which he left again for Ancona, then moved on to Turin and from there he took the way back, stopping for some time in Paris. During his months in Rome, Turner had the opportunity to exhibit, at Palazzo Trulli, some of his canvases. Critics and the public reacted in a mixed way, although negative reactions prevailed. The painter Charles Eastlake, future first director of the National Gallery as well as a friend of Turner’s, reported that a thousand people went to visit the exhibition, “and you can only imagine,” he had to write in a letter sent to a friend in Liverpool, “how amazed, enraged or delighted the different schools of artists were by seeing such new things and methods, so bold, and such unquestionable excellencies. The furious critics, I think, were the ones who spoke the most, and you might hear of a general severity of judgment, but many nevertheless did them justice, and still more were those who took pleasure in admiring what they themselves confessed they had not the courage to imitate.” Unfortunately, the works that Turner presented in Rome are not present, but on display to evoke them is his Lying Venus, an unfinished, rare figure work (thus quite unusual in Turner’s production), a singular meditation by the artist on the Venus of Urbino, which he knew and probably got to see live during a visit to the Uffizi, but which was perhaps also influenced by Canova’s vision of Paolina Borghese: it returns difficult to include it among Turner’s best works, but its presence in the exhibition is further, vivid, relevant evidence of his interest in Italian art.

Joseph Mallord William Turner,

Joseph Mallord William Turner, Joseph Mallord William Turner,

Joseph Mallord William Turner, Joseph Mallord

Joseph Mallord

Joseph Mallord

Joseph MallordSome of Turner’s best work enlivens the next section, which occupies two rooms (the sixth and seventh) and is devoted to Ovid’s Metamorphoses as a source of inspiration. The visitor immediately encounters the Bacchus and Ariadne based on Titian’s painting of the same subject, which had entered the collections of the National Gallery in London in 1826: a late work, from 1840, yet here Turner continues to experiment, particularly on the format, choosing a square canvas (it was the first time he tried his hand at this type), though then placed in a round frame. The painting’s protagonists, whom we see in the center in the lower register of the painting, appear almost as a pretext for insisting on a landscape bathed in dazzling light, an emotional landscape, a landscape constructed with colors, distilled with highly original atmospheric effects that were unparalleled at the time, and that make sunlight a living presence in Turner’s paintings (an anonymous reviewer in the Spectator, speaking of the 1840 Royal Academy exhibition where the painting was on display, branded it as an “explosion of light,” a “splash of sunshine” to be categorized in Turner’s “chromomania extravaganzas.” his painting, even at home, attracted both praise and critique). Nearby are a series of drawings and etchings on themes from Ovid’s book (the small etching with the mythological episode of Procri and Cephalus is particularly successful in its elegance and immediacy). In the next room is a kind of free reinterpretation of a painting by Lorrain: a mythological episode invented out of whole cloth by Turner, Apulia in search of Apulo, based on a character from the Metamorphoses (Apulo, a shepherd who is turned into an olive tree for making fun of some nymphs: the painter invents a story in which Apulo goes in search of his wife Apulia, also Turner’s creation), and set in a landscape that traces a Lorrain view preserved in England, at Petworth House (not in the exhibition, but reproduced on a panel). We do not know why Turner had so slavishly imitated a painting by Lorrain, an artist in whose regard he had a kind of veneration, and whom he continued to seek out in all the landscape views he saw in Italy, as we learn from his writings. The exhibition gives an account of how the painting might have fitted into the debates of the time around imitation of the Old Masters: Turner, in particular, exhibited the work, executed in 1814, at the British Institution, a rival institution of the Royal Academy, which that year offered a prize to the painting that best imitated an ancient work, even though Turner was outside the age limit and, moreover, sent his work late in the competition (the hypothesis is that the artist, with his pastiche, wanted to mock the institution’s ideas about imitating ancient masters).

Lorrain is also recalled in the next-to-last section, the penultimate one, entitled The Perfect Scene and underpinned by the intention to enter Turner’s creative process: a painting with a mythological theme, namely the sketch for Ulysses Mocking Polyphemus, is placed side by side with some watercolors (such as Landscape with Low Sun, also related to the well-known episode from the Odyssey), to show how Turner used the latter medium precisely to sketch out compositions. Turner called them Colour beginnings, or “beginnings of color,” and they consisted of just a few elements, built up with sketchy, fluid brushstrokes but already giving the painter an idea of the luminosity that the final drafting of the painting would have, and which was itself inspired by Lorrain’s light. The works exhibited in this section (to which should also be added the last painting the public encounters in the exhibition, The Death of Actaeon, set in the mountains of the Aosta Valley) are those closest to the best-known Turner, the Turner of landscapes dominated by atmospheric events, the Turner of storms and seas alight with light, the Turner of the sublime: this is the viaticum to the conclusion, the last room displaying the Turin notebook, one of the notebooks the painter took with him to Italy and which holds several views of the city that hosts the exhibition (Turin in the distance, glimpses of the Po, squares, churches, buildings), all of which are, moreover, reproduced, enlarged and arranged in a kind of large cylinder that the public finds just before the exit, which inside holds the original notebook, to protect it from natural light. This is how the city wants to greet Turner: with images of itself reproduced in his shorthand drawings.

Joseph Mallord

Joseph Mallord Joseph Mallord

Joseph Mallord Joseph Mallord

Joseph Mallord

Joseph Mallord

Joseph Mallord

From the Turin exhibition, the first ever devoted to myth in the London painter’s output, enhanced by the very valid and elegant installation by Indian-Turin architect and designer Subhash Mukerjee, emerges an unusual Turner, a Turner to whom one is not accustomed, a Turner who finds in myth a dimension that is congenial to him and that also accompanies him in the elaboration of his most innovative views, landscapes of the sublime, and paintings that anticipate to some extent Impressionism. It is interesting to note that myth, in Turner, is not a momentary infatuation, linked to his stay in Italy, but is a constant that accompanies him throughout his career: his first studies on the characters of ancient mythology date back to when he was a young boy, and certain strands, such as that of Aeneas and Dido, return even in the extreme phase of his artistic parabola. A seventeenth-eighteenth-century legacy, linked to the painters he had always studied, or a disinterested passion? The persistence of the mythological theme in Turner’s paintings, its use, as we have seen, in a sometimes ironic or polemical key, the idea of masking with myth references to current events are elements that point toward the second hypothesis. On the other hand, the debt to the ideal masters and the traditional landscape settings of mythological subjects, a tradition in which Turner was well inserted, and which he had been able to renew in a modern sense, constituted for the English painter an inescapable reference that certainly oriented his choices. Then there is the theme of travel, somewhat in the background, also because it has already been dealt with by other past exhibitions, but nonetheless able to offer interesting ideas to the public, which has the opportunity to measure itself against a good, valid and rather complete exhibition, even if it is composed only of about forty works, but it must be considered that they are selected from the thousands of Turner’s works that the Tate possesses (it is the museum that has the most consistent and extensive nucleus of Turner’s works in the world).

The one on Turner is the second exhibition the Venaria has organized in collaboration with the Tate, following last year’s exhibition on Constable. There is often a tendency to have a certain prejudice against exhibitions ordered with works from a single museum. If, however, the intent is to offer the public an unprecedented project, bringing together works that are usually on display with others that are rarely seen because they are in storage or because they are hidden for conservation reasons, and imagining an exhibition linked to the place that hosts it (the theme of myth, in Turner’s art, is profoundly linked to his journey to Italy, and Turin, as mentioned in the opening, was the first city the artist saw during his first Italian sojourn), then there is no stereotype that holds. The Venaria-Tate “trilogy” will continue in 2024 with an exhibition on William Blake toward which, given the good results of the exhibitions on Constable and Turner, expectations are high. And in the meantime, one will await the forthcoming Turner exhibition catalog.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.