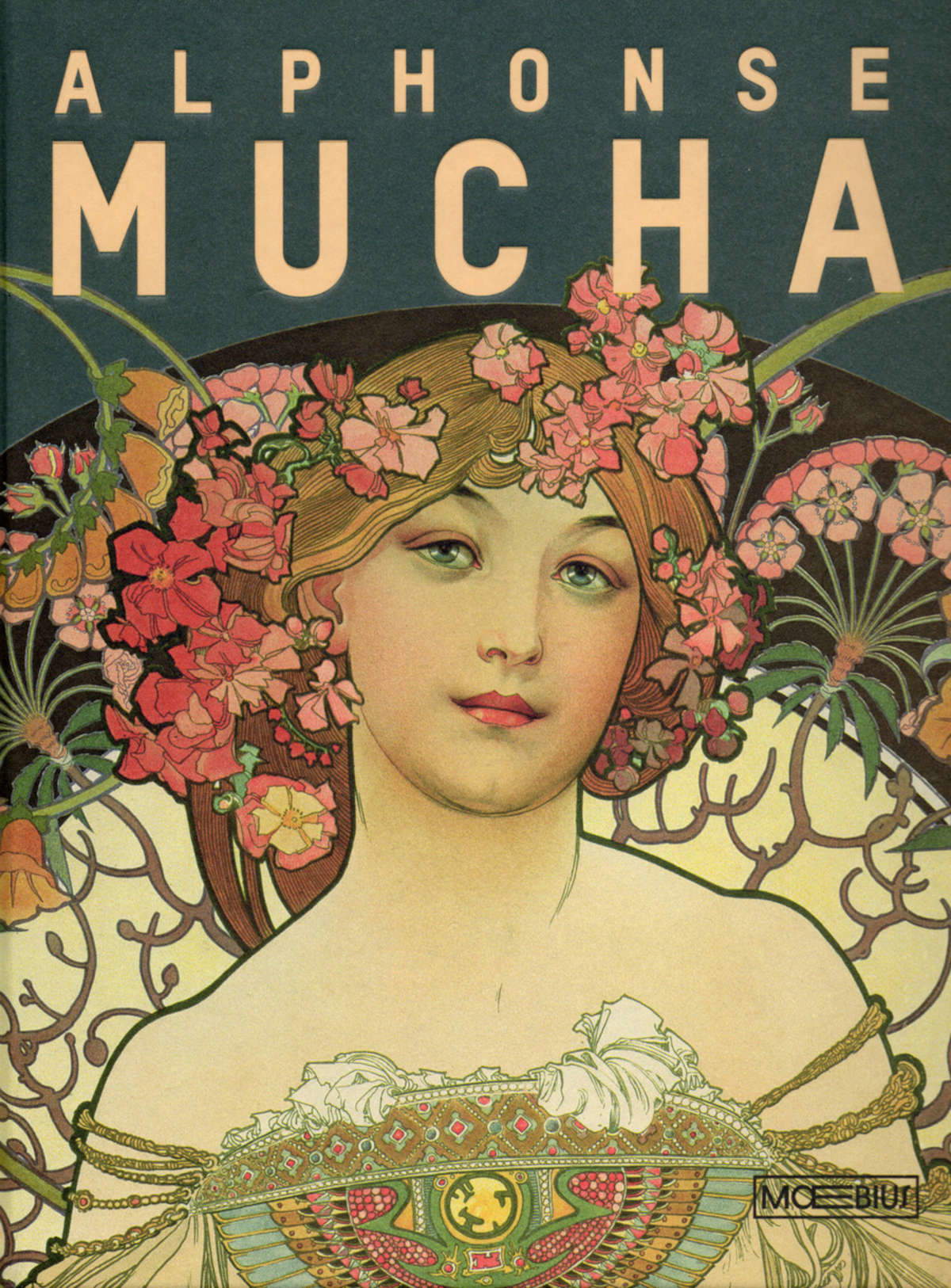

Mucha and Boldini in Ferrara, a glittering exhibition

Sparkling exhibition the one dedicated by the city of Ferrara, in the splendid Palazzo dei Diamanti, to the lovable painting of Mucha and Boldini for this long and captivating spring of 2025. A happy idea that rediscovers a European painter of such high class, aristocratic hand and lyrical temperament as the great Moravian who enchanted Paris, and that places him together with that absolute phenomenon of vivid transfiguration of elegance and feminine charm that revealed the Ferrara name of Giovanni Boldini.

Alfons Mucha (1860-1939), considered the father or the great protagonist of Art Nouveau, and Giovanni Boldini (1842-1931), the Italian pyrotechnician who made all the femininities of France circle around him, were certainly the most happy transporters of European painting to a quivering world of vexatious and poetic self-recognition that became green in its detachment from realism and rose into a long scene of theatrical sublimation, suave and light. In an art-historical sense, a truly important exhibition that stretches the broadest and most beautiful examples of that nineteenth- and twentieth-century side that lies on the other side of the era’s Symbolist immersions and bitter avant-garde labors, to sing the joy of D’Annunzio’s colors, costumes, dances and almost ethereality, restless in the inquiring eyes.

Alfons or Alphonse Mucha set out at a very young age from secluded Moravia to assay in the European woods the prized qualities of an artist he felt within himself and which he was to express in the ways most related to his soul as a poet, a naturalist set designer, an adorner and almost a goldsmith with respect to all the beauties of bodies, chromatic essences, and the jewels that faces and breasts ingeminate. In fact, a fate, which was very opportune for him, landed him in Paris in 1887, giving him a way to assess a fast-changing society seeking its own image of census, and to meet in 1894 the famous actress Sarah Bernhardt, who proclaimed him imaginer of herself in the theatrical art and, at the same time a figurative, certainly poetic, aedo of a West that now enjoyed many wealthy comforts, that is, the soft blankets of advancing industry and easy, and purely colorful, colonialism.

After his meeting with Sarah Bernhardt, the great Moravian’s inspiration ignited even more and haloed the entire figure with an extraordinary ray of floral inventions inexhaustible in beauty and punctuality of execution.

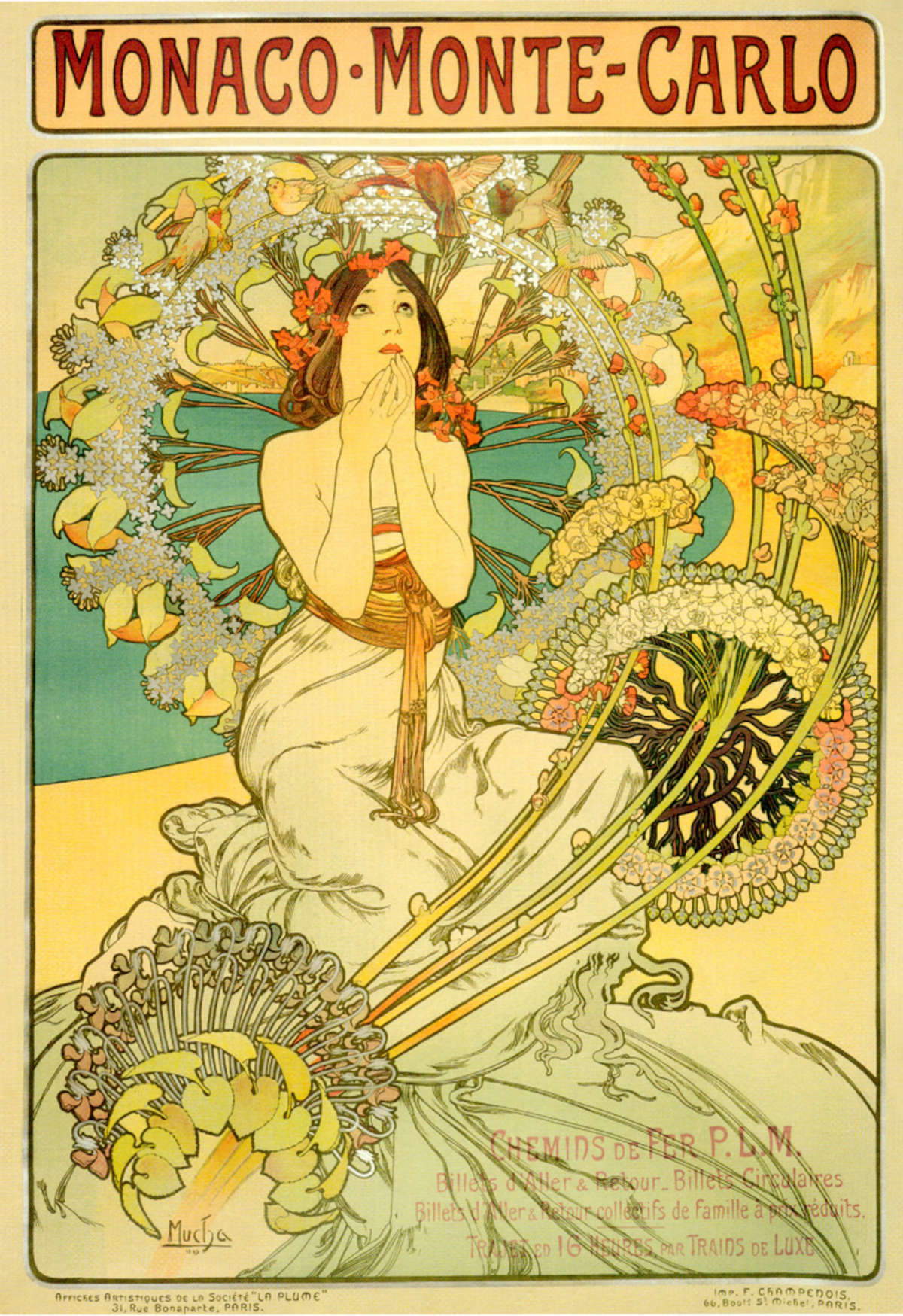

The trepidity of fearful fate at roulette. Dreams, fears, vows, are the exciting charge of a state of mind stretching out in a cosmos of elusive, yet graspable vegetables before a dark cloud. A true masterpiece.

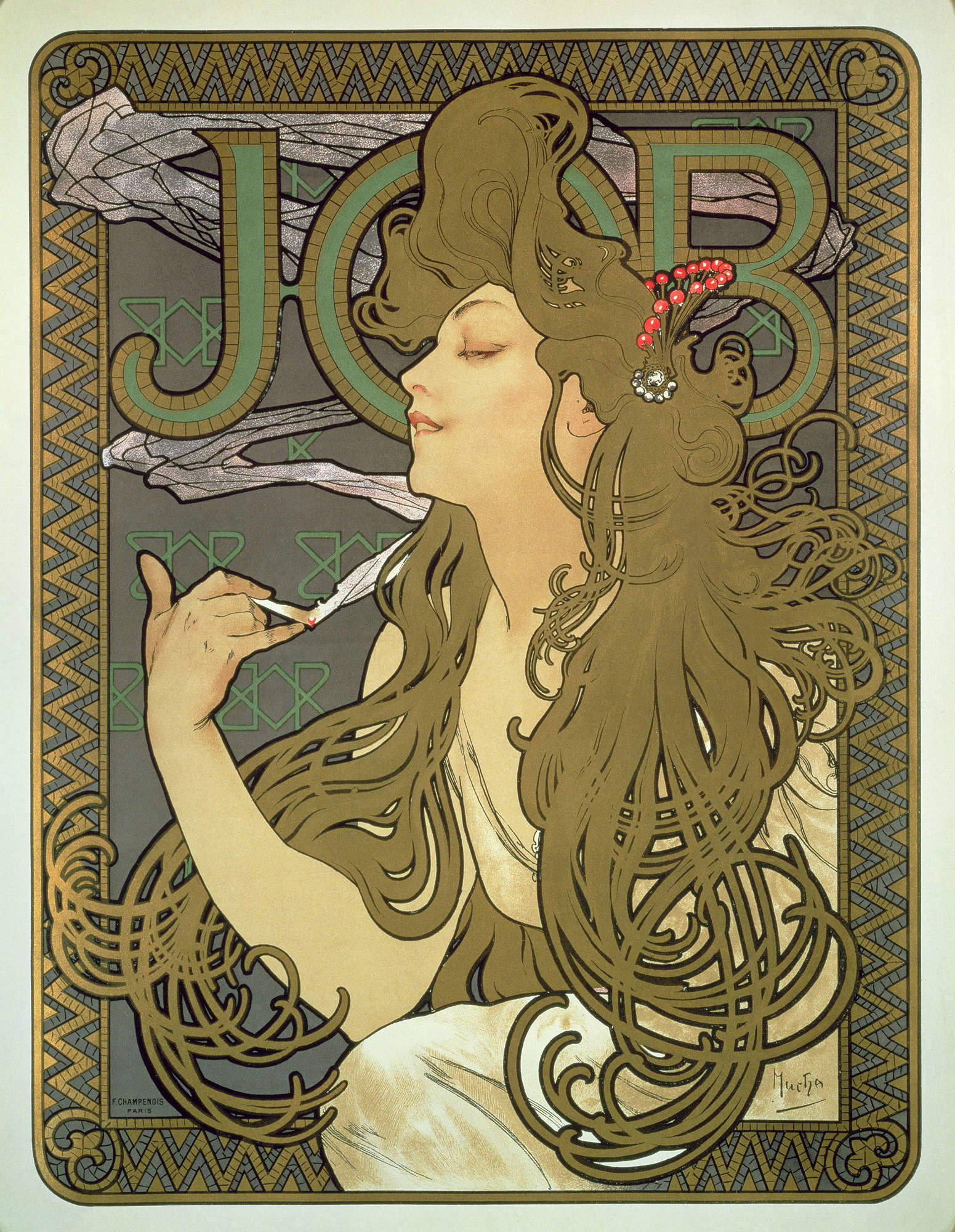

The artist applied himself directly to social life, with advertisements and inserts such as this one, which attracted lively admiration.

The girl offers cigarette papers for sale. On closer inspection she is surrounded by emanations of smoke, in the air and in the waves of her hair, and it is in the intricacies of these, seemingly haphazard, that the great illustrator’s very precise creative control excels.

In this exhibition the visitor will be able to perceive Mucha’s psychic envelopment as he picks up subtle, colorful whispers from afar (silent echoes of remote purities of Byzantium and the Orient) along with limpid childlike naiveté, stilled in dream. Famous figures are often enveloped, almost in polyphony, by rotating rhythms of flowers, by golden, dissolved cadences, by tireless, virentious lines that embrace the view without ever abandoning it and are accompanied by tepid, arpeggiated keyboard colors. And it is continuous the sweetness of the backgrounds, which all around enchants and rests. The celebrated author often accompanies his truly admirable works with convinced phrases that descend from rigid Masonic moral belief, or from the most rorid Christian prayer, to the coveted “Slavic saga,” all his own, of his blood. And the exhibition at one point plunges us physically into prodigious plays of light, mirrors, flashing darkness and self-propelled chromatic and floral paradises, so much so that we cry out in astonishment and exultation. Thus Mucha’s seasons and arts, with its dreamy maidens, make for an unforgettable visit.

Undoubtedly it is Mucha’s fascination that occupies the major part of the exhibition and that holds the importance of the Ferrara event, now strongly hailed internationally according to the participation of eminent scholars who attended the presentation, but the second part of the review rightly (and we would like to say inevitably) discovers the forerunner of the New Art that found in Paris the cradle and the limelight of the protagonism that we now consider indispensable for the evolution of the times: thus the admirable histrion of the bursting and living image, the “new Parisian” who is Giovanni Boldini. He partakes of the idealized conception of reality (a theme that sustains the entire exhibition) with his swirling levity that never abandons the pungent sensuality of the figures, almost their bodily yearnings, under the multicolored swirls of his brushes that we can describe as truly agitated by a magician of Latin blood. Here is Boldini, father of the most stunning and prehensile formal freedom.

The Ferrarese master, whose Museum in Palazzo Massari will soon be reopened, is present with a repertoire that is as significant, sonorous, exciting, and here varied in postures, attitudes, lighting, and execution techniques, so much so that it engages in dialogue or dialectic with photography and early mobile filming, but always from a chair that is that of art.

Mucha and Boldini, writes Alan Fabbri, are present in the exhibition with international acclaim and here they confront each other, for the first time, in one of the highest temples of Italian art which is the Palazzo dei Diamanti in festive Ferrara.

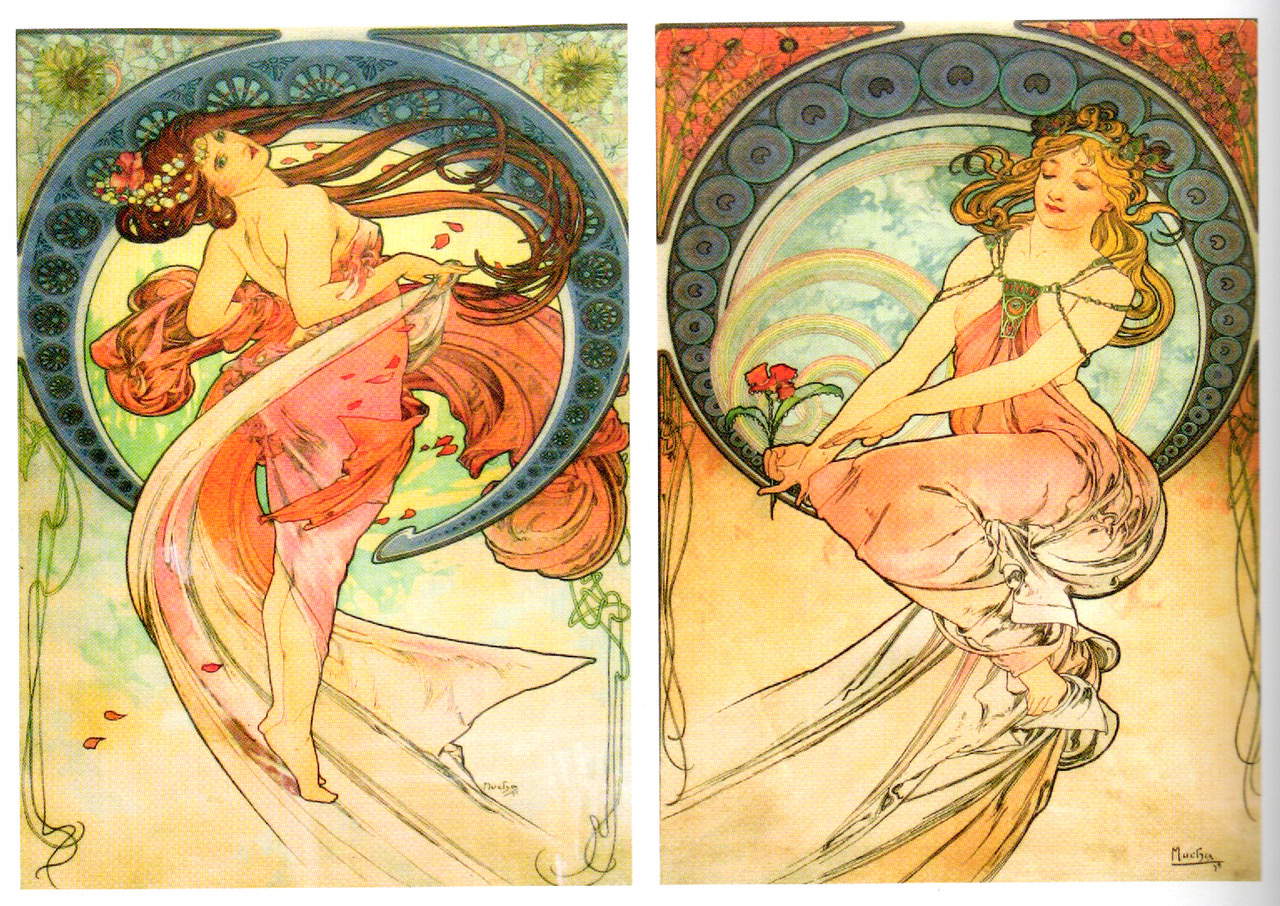

In the decorative panels Mucha excelled: they were easily reproduced and he was very glad that the people also enjoyed them. Here from the standing Dance he switched to Painting, which then-like Poetry and Music-became a seated figure, realizing the highly successful “Q formula.”

Opening the new century, the “Mucha style” became universally established. The beauty of the models, the poses, the richness of the outfits, the hairstyles, the harmonious surrounds of colorful vegetables, and the soft lighting are the faithful but always new components of the visual drafts.

In the advance of cinema and its more reflective age, the illustrator stands alongside the new medium and enhances its intensity. This lithograph carries the thrill of a moment of action that the drawing captures perfectly in the motions of a searing dilemma.

The model is the daughter. The poster is for the second Epic exhibition, held in Brno. Soon the dictators of Europe will meet for a not-so-distant World War II. History quivers. In the background appears the god Svantovic with his four faces, and the harp, played by the maiden, would like to ward off the quivering omen.

This portrait is posed here as a reminder of the forty paintings by Boldini that form the second part of the excultant Ferrara exhibition: they will then remain in the new exhibition venue at Palazzo Massari, but here they offer visitors the most scintillating dialogue between the two poets of feminine beauty who stood side by side in late 19th-century Paris bringing such a vivid canticle into the new century.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.