What might the art of resistance look like if the Marxian dream of revolution had collapsed and the neoliberal promise of salvation proved fraudulent? The group exhibition Mongol Zurag: The Art of Resistance, curated by Uranchimeg Tsultem, illuminates an art-historical lineage of Mongolian painting called “Mongol Zurag,” literally “Mongolian painting.” Mongol Zurag, supposedly, demonstrates an evolutionary path on “how not to be ruled that way,” to borrow Foucault’s words, 1 through the changing regimes of government and political economy from the socialist Mongolian People’s Republic to the current state of Mongolia. The exhibition is a centennial tribute to painter and art researcher Nyam-Orsyn Tsultem, the late father of Ts. Uranchimeg, who is widely credited with the invention of Mongol Zurag as an aesthetic tradition. The exhibition features four artists-Nyam-Orsyn Tsultem (1924-2001), Baasanjav Choijiljav (b. 1977), Urjinkhand Onon (b. 1979), and Baatarzorig Batjargl (b. 1983)-along with a series of archival materials documenting the emergence of Mongol Zurag as a consciously Mongolian aesthetic tradition.

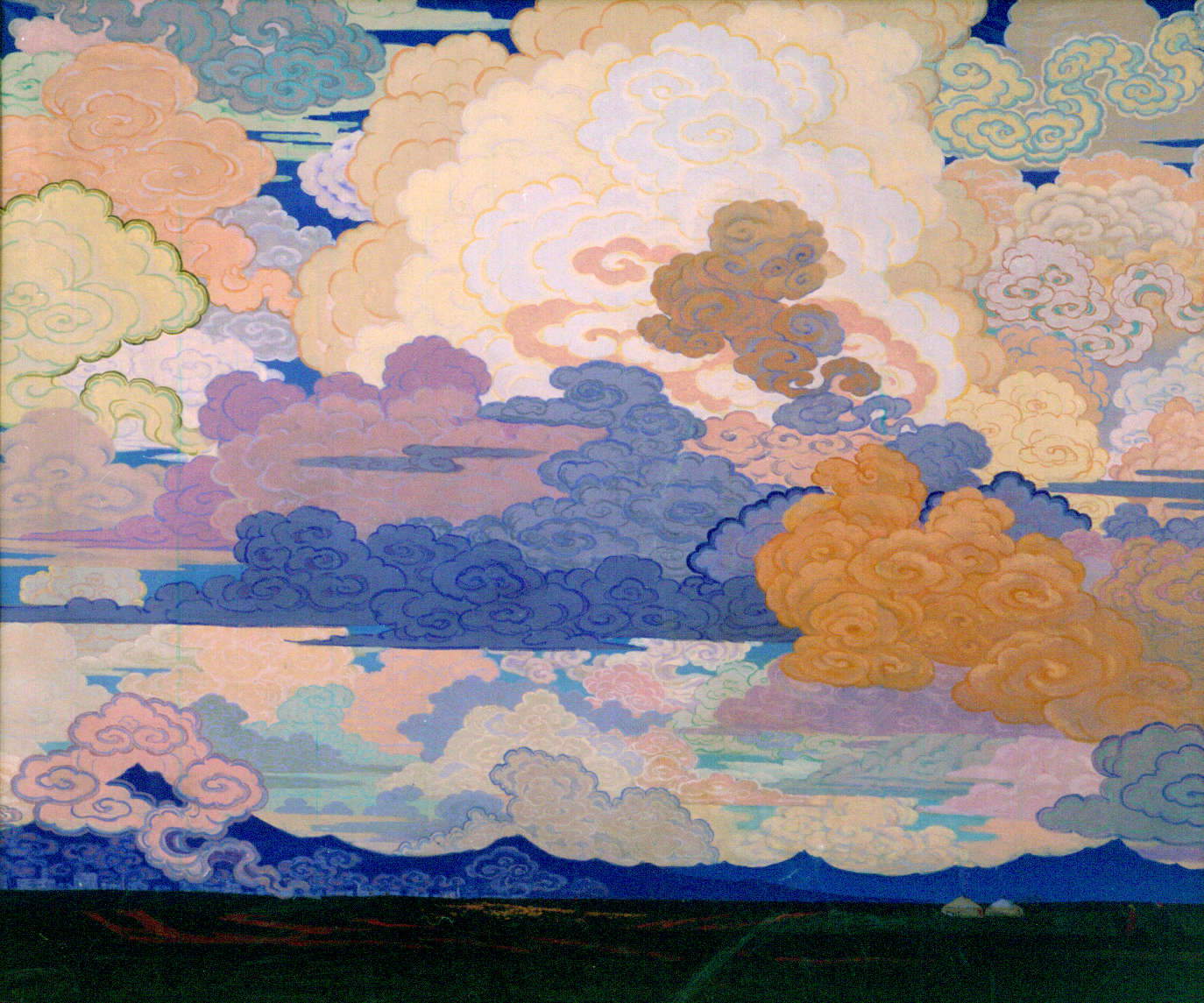

Nyam-Orsyn Tsultem grew up in a Buddhist monastery and was exposed to the arts before becoming a professional painter in socialist Mongolia. In the 1940s he received further education in painting at the Surikov Academy of Fine Arts in Moscow before returning to Mongolia and becoming president of the Union of Mongolian Artists in 1956-89. Tsultem conceptualized Mongol Zurag as an “independent,” “national-style” painting, characterized by its “vivid colors, a flat and decorative quality, bird’s eye perspective, ” 2 “narrative composition,” “refinement of technique,” and sincere and humorous depiction of life events. 3 Mongol Zurag, then, was Tsultem’s aesthetic solution for the survival of indigenous Mongolian culture under the hegemonic influence of the Soviet Union and the ideological control exercised within the Mongolian People’s Republic.

While Tsultem was working at the height of state socialism in Mongolia, the other three artists, Baasanjav, Urjinkhand, and Baatarzorig, represented in the Mongol Zurag exhibition, all belonged to a similar generation coming of age as the Soviet Union collapsed and Mongolia transitioned to a market economy. Unlike the muted inclusion of Buddhist and indigenous Mongolian motifs in Tsultem’s otherwise apolitical paintings, Baasanjav and Baatarzorig’s works are visibly much more political, that is, concerned with the affairs of the state, if one is familiar with visual imagery. Yet, in both Baasanjav’s Rhythms of the Time (2023), which depicts a chaotic transitional scene in which corrupt politicians gallop over defenseless masses on the back of a green horse, and Baatarzorig’s Preaching about Central Asia (2024), which depicts Putin and Mao connected by streams of Campbell’s Tomato Soup, Coca-Cola and Moutai between Mickey Mouse and other symbolic figures from Mongolian Buddhism and cultural histories, the formal characteristics of Mongol Zurag remain intact. Like Urjinkhand, whose paintings invoke human beauty and harmony, Baatarzorig believes that the role of the artist is to create and not simply criticize. 4

In Baasanjav’s Rhythms of the Time (2023), a realm of formal politics and institutionalized culture dominates the composition above a burning field of masses stuck in informal urban settlements with their unanswered political demands. A row of raised hands above a polluted field of gers wooden houses painted red and gray contrasts sharply with the well-dressed, gold-embellished politicians flying away from the masses. A mélange of references to the Chingisiin tug, Maitreya’s Green Horse, and elements from B . Sharav expresses the cultural reshuffling that rose through Mongolia’s political-economic fervor in the 1990s. Turning our view to a broader field of power, Baatarzorig’s Preaching about Central Asia (2024) explores Mongolia’s difficult geopolitical position between its giant neighbors Russia and China, symbolized in this painting through portraits of Stalin and Mao, between whom rode an anthropomorphic Mickey Mouse figure on a horse. Painted mainly in gray tones that allude to the post-shock therapy disillusionment in Mongolia and the persistence of air pollution and corruption that hinder the vitality of contemporary Mongolian lives, threads and rivulets of red flowing from a can of Campbell’s tomato soup, a Coca-Cola, and a bottle of Moutai connect the multitude of figures in the painting, as if to suggest the dependence of Mongolia’s fate on structures of geopolitics and the global economy beyond the hands of Mongolians. In contrast, Urjinkhand’s works in the exhibition would probably not seem “political” at all to many. In Our Life (2021), Urjinkhand uses the Nagtan style of black paintings characteristic of the Tibetan Buddhist tradition to reflect on the human obsession with technology and the consequent loss of communication between human beings during the crisis periods of the COVID-19 pandemic. In Immunity-2 (2019), drawing on Buddhist teachings of inner peace and harmony, Urjinkhand uses the flower motif to visualize a protected sphere of spiritual wealth, symbolized by the Mongolian ger and precious jewels of the Tibetan Buddhist lexicon.

If the Art Biennale of 2024 is about Strangers Everywhere, how would the art world, still centered on an epistemological West that is entangled in colonial claims to the Global, respond to Mongol Zurag, an aesthetic tradition that supposedly embodies a kind of radical otherness from what is known and represented at the Arsenale and Giardini as culturally “queer” and politically “critical”? The queerness and subversiveness of Mongol Zurag must be understood in reference to the art and political history from which it emerged. While the oil or acrylic on canvas is certainly not an innovation in form, the aesthetic détournement of Buddhist, shamanic, chinggisid and other icons, figures and motifs depicted in the content unequivocally constitutes a critical response to the modernist aesthetic legacy of socialist realism in the country. These images constitute not only a kind of resistance against the state domination of aesthetics in a bygone era: they also embody a critique of what “resistance” or “criticality” might look like in contemporary art today. These acts of subversion could be likened to what anthropologist James Scott has described as “hidden transcriptions”: seemingly conventional in visuality, Mongol Zurag challenges the conventional understanding in contemporary art today that resistance should be formally at odds with modernist aesthetics or speak directly about and against politics in content. Without ruling out the possibility of a direct Pararesian 5 representation of domination, violence, or explicit resistance-for example, in the works of Claire Fontaine, Xiyadie, or Ai Weiwei-Mongol Zurag, as exemplified through the paintings of Tsultem, Baasanjav, Urjinkhand, and Baatarzorig, demonstrates a style of “critique of power uttered behind the back of the dominant” expressed openly but in disguised form. 6 Thus, Mongol Zurag criticizes the very notion of “resistance.”

Gayatri Spivak asked in 1988 whether the subaltern could speak. 7 Goto Shinji asked in 1999 at the first Asian Art Triennial in Fukuoka, “Can Asian art talk?” 8 “Mongolian art,” if such a broad category of aesthetic-political stance could be recognized, probably still struggles to speak to Western contemporary art institutions, whether due to language barriers, disparities in material conditions, or differences in aesthetic-intellectual histories that make critical forms differently shaped and articulated. We, whoever or wherever we are, must also be prepared to listen. Mongol Zurag: The Art of Resistance represents an appropriate entry point for the conversation, especially for the Venice audience, with its art-historical significance for Mongolia’s modernity and postmodernity. The group exhibition will be of particular interest to scholars and enthusiasts of socialist art history and contemporary postsocialist art. In addition, the exhibition offers a uniquely Mongolian perspective on post-Soviet decoloniality in the context of ongoing crises in the world today.

Notes

1 Foucault, Michel. 1997 [1978]. ’What is Critique?" in The Politics of Truth, edited by S. Lotringer and L. Hochroth. Los Angeles: Semiotext(e).

2 Uranchimeg, Tsultemin. 2024. Mongol Zurag: The Art of Resistance. Exhibition catalog. Ulaanbaatar: Mongol Zurag Society.

3 Tsultem, Nyam-Orsyn. 1986. Development of the Mongolian National Style Painting ’Mongol Zurag’ in Brief. Ulaanbaatar: Gosizdatel’stvo.

4 Personal Communications.

5 Foucault, Michel. 2001. Fearless speech. Los Angeles, CA: Semiotext(e).

6 Scott, James C. 1990. Domination and the Arts of Resistance: Hidden Transcripts. New Haven: Yale University Press.

7 Spivak, Gayatri C. 1988. ’Can the Subaltern Speak?" in Marxism and the Interpretation of Culture, edited by C. Nelson and L. Grossberg. Champaign: University of Illinois Press.

8 Goto, Shinji. 1999. ’Can “Asian Art” Speak?" in The 1st Fukuoka Asian Art Triennale 1999 (The 5th Asian Art Show). Fukuoka: Fukuoka Asian Art Museum.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.