Michael Sweerts, from the vestiges of Rome to the shadows of the East.

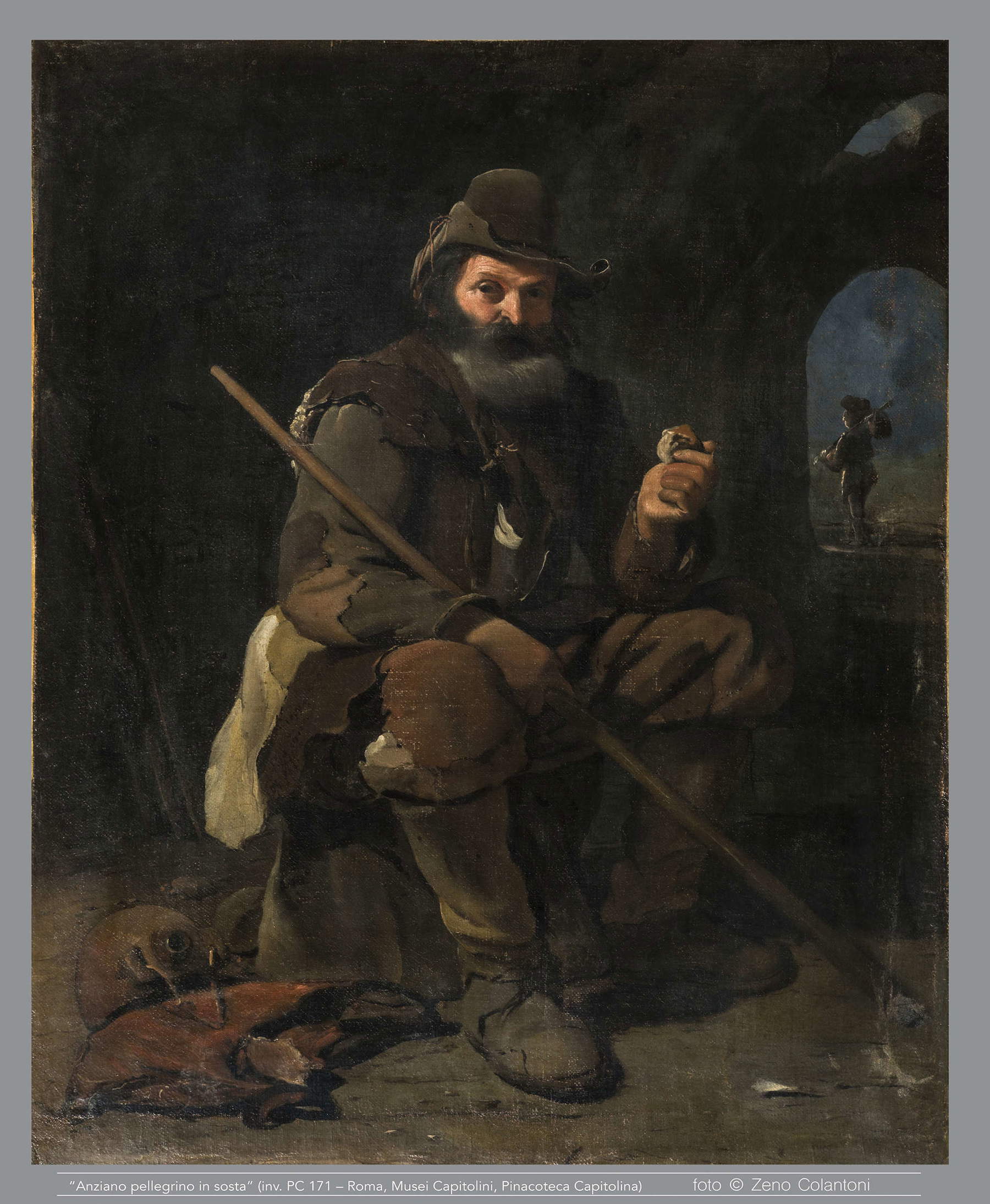

He must have been quite a guy, this Sweerts. From a Flemish family ennobled by the textile trade, Andrea, G. De Marchi and Claudio Seccaroni recall today in the catalog of the exhibition, still running in Rome until Jan. 18 at the Accademia di San Luca, “he asked for and obtained a title that he did not expound, either on the person or on the works.” From which we infer “absolute resoluteness of character.” And so we have introduced the main theme: the mystery hovering around Michael Sweerts, who was born in Brussels probably around 1618 and died in the exotic lands of the Indian East, in Goa, in 1664, where he had thrown himself perhaps in response to a mystical crisis, following the Lazarist mission. "Cavre Suars“ or ”monsù Suars“ in the inventories of Camillo Pamphilj-a nephew of Innocent X, who made him a cardinal in 1644-appears as ”Monsu Michele Suarss fiammengo“ or ”Cavaliere Suars fiamengo," and was in the prince’s service from June 1652.

Thus, the element that weighs most heavily on the critical reinterpretation of the 17th-century Flemish painter, Michael Sweerts, seems to be the limited availability of biographical information. About the honor, for which he himself applied to the pope, the two Italian historians observe, “He certainly did not like those trappings and his own end in distant countries, certainly does not signal someone who intends to bask in privilege.” The obscurity that largely swallows up Sweerts’ origins is similar to that which shrouds the first two decades and more of Caravaggio, about whom very little of note is known before his coming to Rome, indeed almost nothing. And Sweerts certainly studied the Lombard’s works, at least those in the Pamphilj house, but he cannot be called a Caravaggesque in toto.

Because of biographical uncertainty today Sweerts is thought to have arrived in Rome at about 28 years of age, in 1646; the birth indicated in 1618 in the baptismal record is known, which does not, however, reconcile with the data made known by the painter, who gave unreliable information if in 1649 he claimed to be 25 years old and held this reference until 1650-1651, claiming to have been born in 1624-1625, so that at his death in 1664, from the Missions Étrangéres records reconstructed by Kultzen in his 1996 monograph, the painter’s age ranges between 36 and 48. In papers recently found in the Vatican Apostolic Archives, Sweerts says he has been “dwelling in Rome for seven years,” which would anticipate his presence in the Urbe to 1643. Other documents anticipate a few more years. One, found in the Vatican Apostolic Archives, dates from Sept. 25, 1650 and is an application to Innocent X in which the painter asks to be received among the knights of the Golden Spur (the Militia aurata) and says he aspires to it “yes for birth, as well as for being excellent in the Science of Painting.” As for his lack of interest in exhibiting titles, as the catalog points out, he never even displayed the family coat of arms in his own effigies. Yet, despite his noble privileges, even a few decades after his death, news or traces of many of his works had been lost (in fact, before his knighthood, he apparently signed little of his paintings).

Prior to the current one, the largest retrospective that was dedicated to him in Italy was in 1958. It was mounted in Rome in the spaces of Palazzo Venezia and the executive committee included a majority of Flemish and German scholars and some Italian historians, including Giuliano Briganti, Longhi’s pupil who had come to prominence for his studies on Pellegrino Tibaldi and Mannerism and for having curated an exhibition in Rome in 1950 on the “Bamboccianti” to whom Sweerts himself was likened in the Palazzo Venezia exhibition, where, in the introduction to the catalog, it was pointed out that when the great Flemish-German historian Wilhelm Martin devoted some 20 pages to him in 1907 in the journal “Oud-Holland,” Michael Sweerts painter. Outline for a Biography and Catalogue of His Paintings, only 22 attributed works were known of the artist, whereas in the year of the Roman exhibition, “that number has tripled, and we have today also a much clearer idea of the works of his workshop, as well as those of the artists belonging to his circle.”

It would be hard to say that the current skein has actually been much more unraveled in recent decades, if Andrea G. Dee Marchi and Claudio Seccaroni, on the subject of “Novelties on the Life and Works of Sweerts,” introducing the catalog of the exhibition now at the Accademia di San Luca write that “on the terrain of philology, at least twenty paintings out of a catalog of about one hundred and fifty have been untenably assigned to him.” Fifteen canvases in all are the spoils of this retrospective where open questions in Sweerts’ catalog are highlighted. And it is also about attributions that come, for example, from the studies of one of the main commissioners of the 1958 exhibition, Rolf Kultzen-a specialist of Sweerts, but also an interpreter of seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Venetian painting, in particular Francesco Guardi-who, after an initial catalog compiled in 1954, still in 1996 drew up a list in which today the two Italian scholars identify several dubious works: an Osteria, of unknown location; the Good Fortune and the Washerwomen from the Mambrini collection; five canvases with the Senses scattered between the market and the Academy in Vienna; three canvases with Fanciulli, of missing location; a Violinist in the Puskin Museum; a Beggar, much ruined, from the collection of Mina Gregori; and other canvases. This pointing out of the fallacy of certain attributions is relevant, because it signals a widespread deontological problem among connoisseurs active today: for several decades now there has been an extensive tendency to catalog artists-think of Caravaggio and Artemisia, but lately also various Flemish ones: with risky speculation regarding the Caravaggesques on copies often mistaken for originals-which fuels a market often devoid of inhibitions to ensure the reliability of the antiquarian trade.

On Sweerts the timing of critical examination has changed greatly. At the time of the Palazzo Venezia exhibition he was still referred to as a “bambocciate” painter, very active in his own workshop in Rome. Indeed, the title Michael Sweerts and the bamboccianti testifies to the fact that even then Briganti’s studies were beginning to bear fruit and nurtured a discerning collector. The curators of the 1958 exhibition recalled precisely that for some years Roman architect and art historian Andrea Busiri Vici had been pushing for a Sweerts exhibition to be mounted in Italy. Busiri Vici had become a connoisseur of the Flemings, and Briganti himself in 1989, in the journal “Studi Romani,” celebrated his passing by also drawing a portrait of him as an expert: “He was undoubtedly a pioneer of that taste for seemingly marginal episodes of seventeenth- and eighteenth-century artistic culture (the bamboccianti, for example, or the Italianizing vedutisti and landscape painters) that spread even outside Italy in the 1960s and 1970s.”

If already in the 1920s the Russian-born historian Vitale Bloch turned his attentions to Sweerts and in 1950 expressed a desire to mount a retrospective at “Cavalier Suars,” rediscovery was still in full swing when in 1968 Bloch published in France a well-illustrated essay that also considered the existential epilogue of the painter, after 1660 (“fled” with Catholic missionaries to exotic lands), entitled precisely Michael Sweerts. Suivi de Sweerts et les missions etrangeres par Jean Guennou. It should be added that the director of the Boymans Museum, Ebbynge Wubben, introducing the Palazzo Venezia exhibition recalled that in the group show held in London in 1955 on seventeenth-century artists in Rome, Sweerts’ painting was compared to the “Metaphysics” of De Chirico and Carrà; adding: “In spite of the plastic effects they achieve, through resentful modeling, Sweerts’s figures are absorbed, isolated and static even when they gesture or seem to seek an exchangeable communion...The artist prefers the dying light, such as that of the evening, so that the paintings are bathed in a melancholy atmosphere. The genre motifs, taken from the life of the Roman people, are executed according to classical and academic rules: realism and academicism.”

But Franz Roh’s observation that “slight, precious contrasts” were taking shape in Sweerts was not off-center. After all, these are the same forcings noted by a part of Caravaggesque criticism in the “classical” interpretation of Merisi, whose painting manifested in Rome a rebellious genius whose choices were unwelcome to a part of the more clerical; in this sense, even the making use of chiaroscuro has been artfully understood as a weapon to enclose Caravaggio’s revolution in darkness-naturalism.

Following the observation of Emilio Lavagnino, the art historian and Lazio superintendent who was pulling the strings of the Palazzo Venezia exhibition, that Caravaggism-when Merisi had been dead for five years and Ribera had directed the research of many of his followers (this was seen better thanks to Gianni Papi’s studies) - “in Rome, around 1615, would be said to be in the midst of a revival, also due to the very valid intervention of some Flemish and Dutch artists, until, immediately after 1625, it seems to want to rapidly mitigate the violence of its lights.” While he seems to want to uphold the weight of Sweerts’ example, Lavagnino makes it more ambiguous when he speaks of a new Caravaggesque idea advanced by the Dutchman Pieter van Laer, linking the 1950 exhibition on the “bamboccianti” held in Rome’s Palazzo Massimo and the following year’s exhibition in Milan on Caravaggio and the Caravaggesques, curated by Longhi. The world of the humble celebrated by Caravaggio and his disciples-“until then rejected by any official representation,” because it lacked “decorum”-would, on the other hand, be, more than a century later, albeit with a free-range and earthy discard like Ceruti’s, the Caravaggesque line also pursued by Sweerts precisely because of a new and open vision of the last, disenchanted, that is, not prone to pauperism, that is, in the Flemish’s case, without an ideological forcing as might have stemmed from the Borromean tradition that still plowed the lands of Brescia and Bergamo. Not “incidents and little stories, characteristic of the petty people of the beggars, bag-cutters, guitti, and charlatans” that Bellori precisely saw turned polemically on behalf of the wretched toward that society of clerical and notarial sphere; in fact, as far as Sweerts was concerned, more attentive to the subtle contradictions that always reveal the common mixture of good and evil that makes men noble and miserable without predetermined recipes. It was disappointing, I think, for Sweerts himself to think back to the Lutheran pride of “those Reformed men who returning to their limpid cities of Northern Europe with certain precise images in their luggage could prove, documents in hand, that in the great city of the popes it was not all gold that shone.”

Would a painter of today’s younger generations know how to play with irony on classical forms as Sweerts knew how to do by standing precisely in the balance between realism and classicism, lowering himself into the same tools of the academy, the plaster casts that we see again like a cemetery of relics in his canvases where he depicts an artist’s studio? “He lived and painted differently from the clichés of the time, showing unparalleled attention to the real lives of the subjects of different classes he depicted,” De Marchi and Seccaroni comment. But he loved to practice teaching students who sought in the academy the starting point for acquiring the best tools of art. Drawings, cartoons and the use of type also returned in his own paintings. And several were indebted to him for these patterns that were repeated. With Johannes Lingelbach, the friendly exchange also generated an exchange of graphic models. But as the curators note, Sweerts “appears uninterested in fashions and in creating for himself a host of followers” on whom to impose his own magisterium; in fact, “few works can be ascribed with certainty to the workshop ... that are distinguished from replicas and rare copies.” The result is a nonconformist approach “capable of coexisting misery and elegance, moving away from iconographic repertoires considered more noble.”

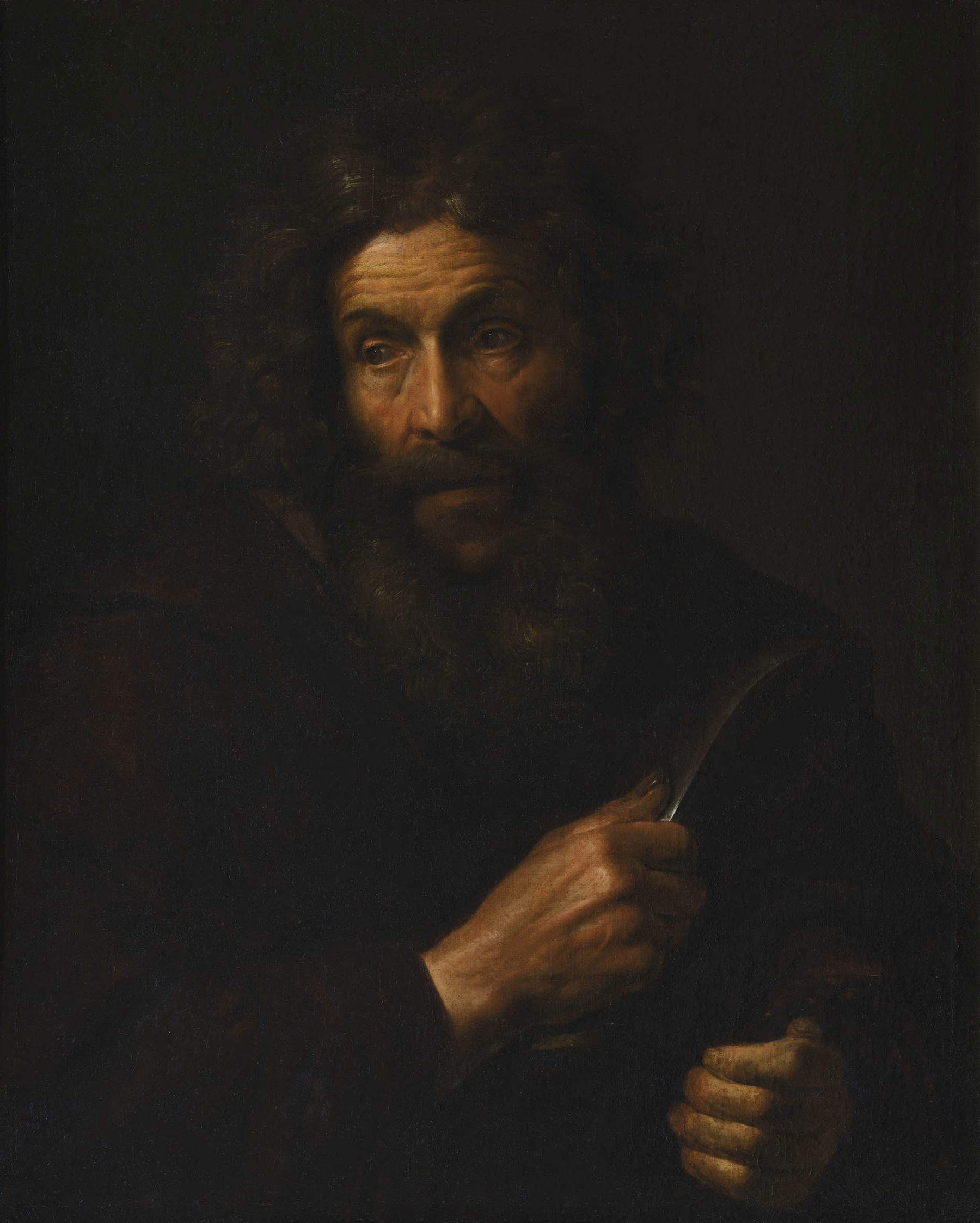

Regarding the mystery that still hovers around him, De Marchi and Seccaroni note that confusion often arises even over the somatic features of his face, “incompatible with each other and with the most unreliable identikits.” In the meantime, one must stick to the definite matches. One is his Self-Portrait of about 1645, preserved in the Uffizi, while another canvas, again with one of his Self-Portraits from a few decades later, when he had already returned from Rome to Brussels and before his departure for the East: by now a mature man, he is elegantly posed in clothes that are not at all sumptuous, as he paints and looks at us against the background of a landscape bathed in a serene light that emphasizes his face with an aura out of time. We are probably in 1659 and Michael appears anything but submissive, indeed a difficult character stands out, intransigent as Claudio Strinati defines it, ready for discussion even over rhymes, with a willingness to challenge and a need to find inner peace, which are perhaps also connected to a personal datum, his alleged homosexual inclination, according to Lindsey Shaw Miller’s research, which the curators with some diffidence call gay drama.

His search for a religious landing place is also a topic of discussion; fairly little is known, but his flight to the East seems induced by conversion, which soon also led him to disagreements with the very missionaries who had welcomed him into their company. A soul in pain? Certainly, as Dominique Cordellier titled one of his essay-narratives a few years ago, Le peintre disgracié: Sweerts was a dissatisfied and melancholic man. And perhaps his poetics, which he called “caught up in life,” was meant to bring out the “bitter” feeling that links precisely irony and perception of the inexorable wearing out of time, that is, of himself. His canvases of beggars, drinkers, spinners and the groups gathered outdoors in small landscape situations, seem to resolve themselves into a strange “serene” state of mind, where the achievement of balance makes his human effigies almost insensitive to the tragic nature of life, as if everything had to happen and the final outcome emerged from an ironic procedure. A very Nordic form of skepticism in manner.

The two curators take a decisive step, beyond what had already been established by previous scholars, by looking for physiognomic correspondences among the characters portrayed, to define both a more stable face of the painter and the models he employed that return in different canvases and also diluted in chronology. “Among them, for example, was a man with short hair and a shapely beard, whom he portrayed at least four times, the last of them now connoted with signs of aging.” Same comparison with the girl combing her hair, of which we find two similar canvases in the exhibition but with important compositional differences: in both in the lower right corner, left on the floor, is a basket with cloths (an almost Caravaggesque still life), while in the foreground of the Accademia di San Luca canvas, in addition to the girl holding a mirror on her legs, another standing helps her. Behind, on the left, we see an opening bursting out of the house, through which a man with a cloak and hat is entering; in the tena of a similar subject, kept in Florence in the Museo di Casa Martelli, the girl is in the same pose, below the basket with clothes, but now she is alone: both the woman who was helping her comb her hair and the man in the background have disappeared. The subject matter that is smoother in form and more solid in color, and the simpler composition, could make this canvas precede the other, considering, as has been pointed out by Kultzen, that the scenes with more figures represent an evolution in Sweerts’ path. The subject and its realization have solicited both juxtapositions with the Vanitas types, as suggested by Lavagnino, and a reference to Caravaggio’s Magdalena Doria: De Marchi in this regard recalled that Sweerts had to see her in the Pamphilj house precisely at the time when the pope was granting him a knighthood. Another element that underscores Sweerts’ scholarly expertise is the correspondence of the girl’s clothing with the Roman fashion of the second decade of the seventeenth century. All of this denotes a meticulousness of study, confirming the confident character he exercised for so many years with his academy students.

So why did he decide to leave for the East when he was by then an established and praised painter? In a March 1661 letter to St. Vincent de Paul (already dead), a missionary calls Sweerts “one of the greatest painters in the world, if not the greatest,” one who donates what he earns to the poor, confesses often, sleeps on the hard, eats little and almost never meat. A true mystic, so to speak, despite his business and social savvy personality. Because of his language skills and habit of dealing with nobles, he was a perfect candidate for missionaries. Their close association with France’s foreign policy (see today the function of Abu Dhabi and Singapore), was to further the national interest in competition with Dutch merchants.

In September 1661 Sweerts left for the East. And soon the complaints began, where they came to call him hypercritical: “He becomes insufferable, he lectures everyone. He doesn’t care about the priesthood, in short about all things; in company he contradicts everyone.” Rightly De Marchi and Seccaroni object that they cannot say whether it was psychiatric crisis or whether Sweerts had soon opened his eyes to the “extrapastoral motives of the initiative, not sharing them.” In the final part of the voyage, the editors write, perhaps he embarked for India where he was abandoned battered in Goa. Or, he was directed there by the Carmelites of Isfahan who were based there. But other leads speak of a “noble painter” on India’s east coast who portrayed local dignitaries. The tomb has never been found. Again, albeit with due differences in personal history, Sweerts’ end has strange similarities to that of Caravaggio whose tragic death is still not fully clarified. An end that distinguishes Sweerts, the curators conclude, from the “customs proper to the artists of the time.”

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.