Carlo Bertelli was convinced that Masolino da Panicale’s voice had begun to take on an “already entirely personal” timbre in Empoli’s works. The scholar had in mind especially Christ in Pity, the monumental fresco that a then already 40-year-old Tommaso di Cristoforo Fini painted, it is not known when, for the Baptistery of San Giovanni Battista. And yet, on closer inspection, in that turn of years and in the Tuscan land there has perhaps been no artist who has modulated his tone of voice in as sophisticated, experimental, guarded, composed, suspended, curious a manner, proceeding by trial and error, approaches, departures, reconsiderations, with finesse, measure, balance, openness, prudence. In short, perhaps there was never a time when Masolino was not an artist marked by an attitude all his own. At least as far as we know about him, since on the first forty years of his career we have to sail through the documentary void: Masolino is an artist who emerges from the records when he is by now a done painter and when his fame has already crossed the borders of his native land, the Valdarno of Panicale near Castel San Giovanni (where, moreover, Masaccio would be born a few years later), and not the Umbria of Panicale overlooking Trasimeno. Masolino is an artist who emerges from the mists of history in the year 1423, the time to which the first document about him dates, and which certifies him, dated January 18, as a member of the Arte dei Medici e degli Speziali, that is, the guild that brought together not only physicians but also artists, and the time to which his first dated work, the Madonna of the Kunsthalle in Bremen, dates. The following year, Masolino was in Empoli, painting in the church of Santo Stefano.

Precisely 1424 is for Empoli a kind of annus mirabilis, a year in which some happy convergences add up: Bicci di Lorenzo is hired to paint a triptych in the parish church of Sant’Andrea, while Masolino is summoned to the church of Santo Stefano to paint first the decoration of the sacristy door and then the chapel of the Compagnia della Croce. Masolino’s story revolves around what happened in Empoli that year, and the critical reconstruction of his profile from there had to start. Natural, then, that it was Empoli, and on the exact six-hundredth anniversary of Saint Stephen’s exploits, to host the exhibition so far able to gather the largest number of works by the Valdarno artist. Empoli 1424. Masolino and the Dawn of the Renaissance, curated by Andrea De Marchi, Silvia De Luca and Francesco Suppa, and divided between the city’s two most “Masolini-esque” venues, namely the Museo della Collegiata di Sant’Andrea and the church of Santo Stefano itself transformed for the occasion, aims first and foremost to investigate thecontribution of Empoli in the elaboration of that “third way to the Renaissance,” as De Marchi calls it, that Masolino had in fact opened and on which he had routed his own production, especially after his encounter with Masaccio, an inescapable subject for any reconnaissance on the artist. In parallel, it is an opportunity to take stock of the developments in Masolino’s own art and to formulate new hypotheses on the roads taken by the artists active in the city during that dense juncture. Roads that, moreover, also intersect those of the Renaissance: Masolino obtained the commission to the Brancacci Chapel because, as Carl Strehlke hypothesized in 2007, he was advocated to Felice Brancacci by Carlo Federighi, commissioner of the sacristy of Santo Stefano and friend of Brancacci, with whom he had also left on a diplomatic mission in 1422, thus shortly before the Florentine commissioned Masolino and Masaccio to carry out the celebrated decoration. And then, in the chapel of Santo Stefano, also commissioned by Federighi, there must have been, according to a hypothesis by Silvia De Luca formulated precisely on the occasion of the exhibition, a significant triptych by Lorenzo Monaco, moreover on display in the exhibition, dating from a decade earlier. And it is precisely from Lorenzo Monaco that Masolino’s path can be said to start.

It must be premised that organizing an exhibition on Masolino is not an easy business: there are few of his known works, scattered around the world, and therefore it is not easy to see an exhibition that manages to gather all that can be gathered. The Empoli exhibition lacks a few pieces that would have been more than pertinent: yet it is surprising to observe, on the same wall, works that, with admirable synthesis, offer a rather complete overview of the evolution of a complex artist like Masolino da Panicale. But you get there step by step, because the exhibition begins with the context, starting from the Museo della Collegiata, where the first two sections are set up (those who want to start instead from the church of Santo Stefano will count on immersing themselves in a kind of cinematic flashback ).

The earliest works, fragments of a polyptych by Niccolò di Pietro Gerini framing an early 14th-century wooden crucifix by a follower of Giovanni Pisano, and a Madonna of the Girdle by Lorenzo di Bicci, the central compartment of a polyptych that was in the chapel of theAssumption in Santo Stefano, have above all the function of introducing the public to the lively context of Empoli in the early 15th century, to a city that grew thanks to trade and the good management of a rich bourgeoisie that knew how to administer it intelligently: normal that, at some point, it became a pole of attraction for artists, especially for artists who were linked to Florence. Of course, we are talking about a center in the province, where artists typically worked who “could no longer find space on the Florentine market, which was much more up-to-date and competitive,” as Silvia De Luca points out: yet, despite this, “there was no lack of events of notable importance for the caliber of the artists involved and for the size of the places invested by these operations. That of the various Niccolò di Pietro Gerini and Lorenzo di Bicci (to whom one could add other artists, such as Mariotto di Nardo for example, present in the permanent collection of the Museo della Collegiata: the exhibition has in fact been set up in the middle of the rooms, with the works included in the itinerary recognizable because they are marked by captions with different, though not so immediate, graphics) is an essentially fourteenth-century setting, linked to the Giottesque modes of theOrcagna and the artists who looked to him, and which would be somewhat modernized in 1404 with the arrival in Empoli of Lorenzo Monaco, who introduced into the city a ”breeze," as the exhibition curators call it, of international Gothic: this breeze arrives with the triptych that the friar painter painted for the church of San Donnino, which is now housed in the Museo della Collegiata di Sant’Andrea, and which also makes Empoli a decidedly up-to-date center, since Lorenzo Monaco’s work for San Donnino is among the earliest attestations of late Gothic in Tuscany.

The second section of the exhibition shows, therefore, how the Empolese area had to react to the arrival of Lorenzo Monaco, along a span of time that is indeed rather long, since we move from the polyptych compartments of Scolaio di Giovanni, the remains of a dismembered triptych executed also for la Collegiata, to the panels of a Rossello by Jacopo Franchi who shortly before the middle of the century is still an artist extremely true to himself, and a good forty years later Lorenzo Monaco’s triptych is still caught up in calligraphic flourishes, tapering effusions, nostalgic sighs exhaled while the author was evidently thinking of some dukesque model with whom he must perhaps have felt a certain affinity (look at the Madonna and Child loaned by the Museo di Santa Verdiana in Castelfiorentino to find easy confirmation). Lorenzo Monaco’s triptych, in turn, was a response to the finesse that Gherardo Starnina had brought back from Spain (in which the aforementioned Scolaio di Giovanni shows an enduring interest: he is among the artists most receptive to Starnina’s suggestions in the Empolese territory) and to the innovations that Lorenzo Ghiberti was elaborating from 1401 onward in the north door of the Baptistery of Florence: this is also the context on which Masolino’s art sprouts.

The protagonist of the exhibition enters the scene in the church of Santo Stefano, revolutionized for the occasion with a temporary set-up that is not exactly exciting (it follows the course of the nave, thus closing the view of the side chapels) and also a little tortuous, because the various sections of the exhibition intertwine, often forcing one to retrace one’s steps (the positive element, if we want to see it that way, is that the path thus constructed induces the public to make continuous comparisons and to question with some insistence what they are looking at). In any case, Masolino arrives almost immediately: he is first appropriately introduced by the Master of the Strauss Madonna and the Master of 1419, inserted at the start of routes as early colleagues with whom Masolino shares the desire, conscious or not, to reform late Gothic painting by seeking a more natural and more substantial rendering of the figures, without, however, abandoning the scheme laid out primarily by Gherardo Starnina. This can be seen most clearly in the Madonna and Child by the Master of the Strauss Madonna, lent by the Bargello Museum, a panel in which the refinement of an essentially late Gothic design yields to a massive dose of Giottesque robustness: Doubt will remain as to the degree to which the operation conducted by the master is accurate, that is, whether it is the actual and sought-after desire to set up a new and alternative language, or whether the master in question was motivated above all by the intent to mediate, turning his gaze sideways toward Stranina and backward toward the neo-Giottesque in order to project his painting toward an elegant solidity. It is a reasoning, however, that does not seem to touch much on the early Masolino, that of the highly sophisticated Madonna dell’Umiltà that arrived on loan from the Uffizi, a work that, because of its marked late Gothic accent, can be considered a youthful painting, executed by a Masolino probably in his thirties, or at any rate several years before the Empoli works that already mark a substantial change. The work, given by Alfred Scharf to Masolino as early as 1932, evidently originated as a precious panel for private devotion, and is perhaps the clearest evidence of Masolino’s alumnuship at the workshop of Lorenzo Ghiberti, a circumstance also mentioned by Vasari in Lives: for the Aretine historiographer, indeed, Masolino would have trained as a sculptor (he was, according to Vasari, “the best rinettatore Lorenzo had,” “in the cloths of the figures he was very right and skilful, and in rinettare he had very good maniera et ingelligenza; for which in chiseling he made with more dexterity some dents softly, as well in the human limbs as in the cloths”). Poses and drapery speak the same language as Ghiberti’s North Door: the knee of the Madonna protruding amid the iridescence of the robe struck by the light and the course of the drapery falling to the floor giving rise to that sinuous train enlivened by the glow of the light source are to be found, almost punctually, in the Saint Ambrose of Ghiberti’s enterprise. Masolino is not, however, a mere rehash of the master’s solutions: that delicate and diaphanous grace which is substantiated in the very tender flesh tones, in the elongations beyond measure, in certain somewhat prissy elements, such as the slightly inclined head, and which makes this Madonna look like a most elegant phantom, is his own prerogative, capable of identifying him already at these heights as an original artist, already capable of departing as much from the master as from his neighbors Lorenzo Monaco and Gherardo Starnina, the former more marked by a kind of abstractionism that would have remained alien to Masolino, and the latter instead attracted by flourishes and preciosity that would also leave the young Valdarno artist indifferent.

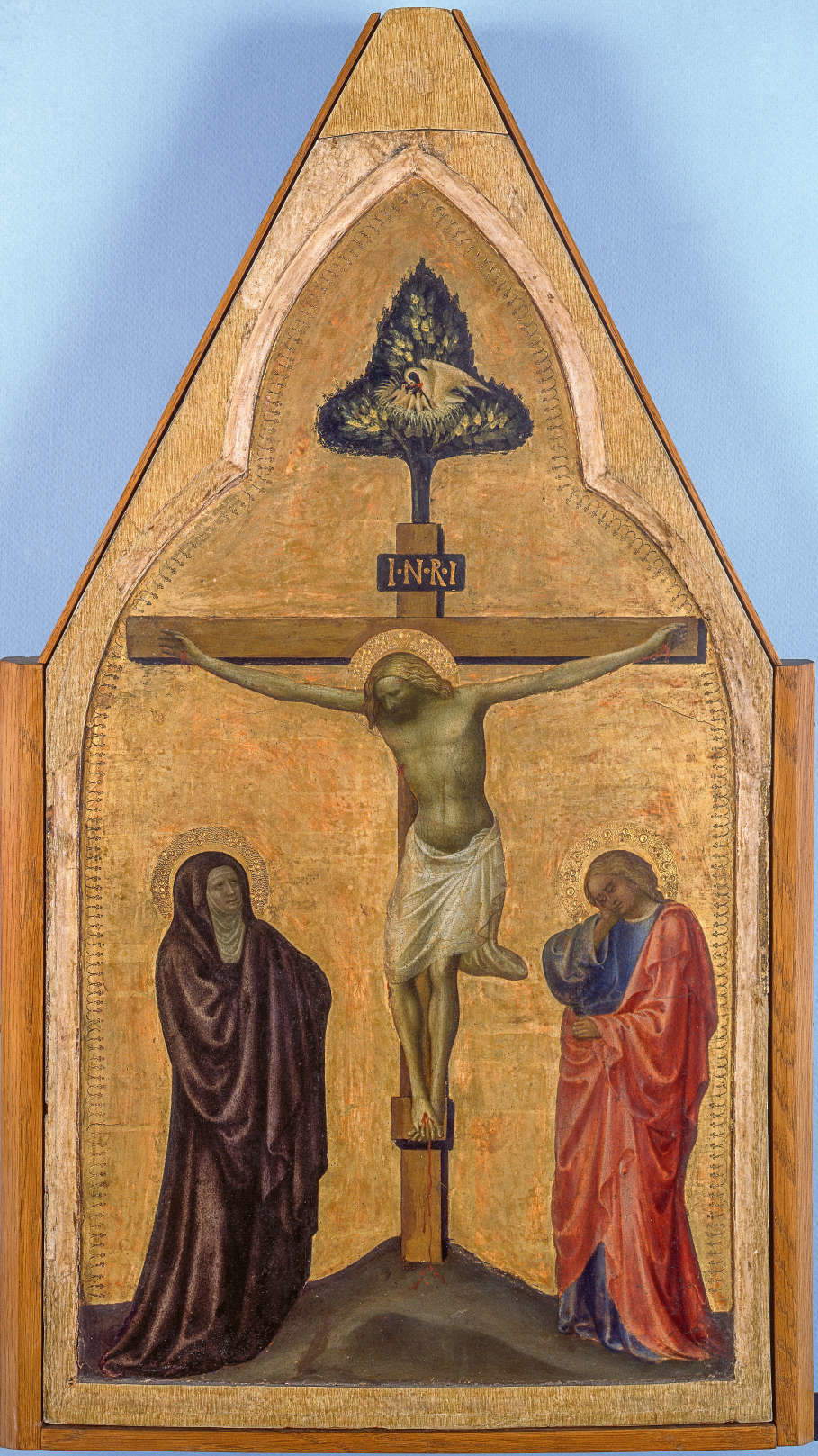

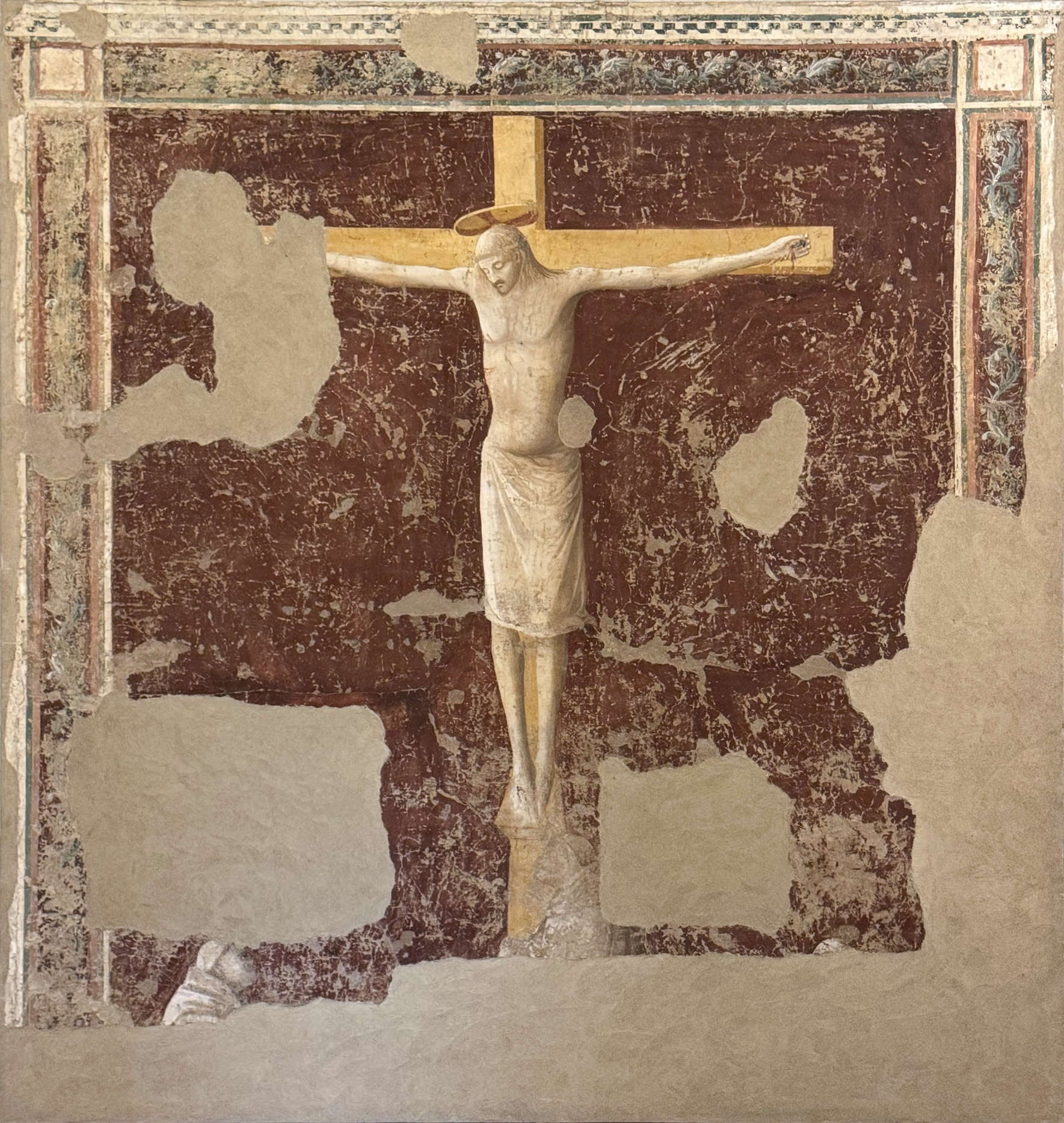

The Madonna of Humility joins one of the main novelties in the exhibition, an unpublished Saint Francis from a private collection, a panel that was once part of a polyptych, and which is stylistically to be placed at a date close to that of the Uffizi panel, although the germ of a more pronounced naturalism, which here is resolved (as for many at the time) in terms of a reflection on theperiod) in the terms of a reflection on late 14th-century neo-Giottism (“evident even in the grip of the left hand on the book, a plasticism that paradoxically coexists with levity of nuance and fragility of gesture that is wholly Masolinian,” De Marchi observes), hints at new impulses that would later result in the more solid Masolino of the Empoli frescoes and especially in the Masolino who thinks at length about his encounter with Masaccio. What must Masolino have been thinking on the eve of that significant encounter? The answer should come from the St. Julian of the Diocese of Florence, displayed along with what should be his predella compartment, the violent scene with St. Julian killing his parents from the Musée Ingres Bourdelle in Montauban: Masolino probably thought it was time to break away from the rhythms of Lorenzo Ghiberti, without, however, abandoning the subtleties learned in thevery active sculptor’s workshop, directing his research toward the courtly world of Gentile da Fabriano but also looking, albeit superficially as Silvia De Luca observes, and perhaps even a little distractedly and certainly unconsciously, at Donatello, since the pose of the San Giuliano would seem to recall that of the San Giorgio. Also looking to Gentile is the Crucifixion in the Vatican Pinacoteca, and to show how this interest of his in the Marche artist’s art was neither coincidental nor shared by other greats, the curators have arranged it in the same section (although in fact, in the visitor’s itinerary, s’encounters a “room” further on) Beato Angelico’s Madonna di Cedri, arriving from the Museo Nazionale di San Matteo in Pisa, to show how, in the same years, that is, at the beginning of the third decade of the fifteenth century, Masolino and Beato Angelico were sharing the same concerns. The sinopia with the Pasce oves meas scene introduces the theme of the encounter with Masaccio: it is a pity not to be able to see in the exhibition the Uffizi’s Saint Anne Metterza , which would have been perfect in the Empoli itinerary, even though it is among the most famous images in the history of art, a singular panel in which the two artists see themselves together, with the young Masaccio already projected into a new epoch, and the older painter who is surprised and fascinated by the novelties imposed by his colleague, and attempts a reaction that, in the exhibition, we see in perhaps the best-known masterpiece, the Christ in Pity mentioned in the opening, and which occupies a wall of its own. It is Masolino’s most Masaccesque work, a watershed in his career, a work in which, writes Silvia De Luca, “the painter’s late Gothic temperament is relegated to the wholly decorative conduct of the cymatium and the careful rendering of details, such as the veins of the cross or the traces of blood at the nails.” Masolino, here, looks ahead: the tomb is foreshortened in perspective, the body of Christ is set in volumes that try to approach those of Masaccio, the composition itself tries to be credible, natural, tries to draw the attention of the relative to the pain of the Virgin and the Magdalene. Little to do with the neighboring lunette where the artist, while retaining his innate elegance, “even seems to be invested by a stroke of the tail of early 20th-century neo-Giottism,” as De Luca writes.

Masolino, in any case, is an artist of reference for understanding what was happening in Empoli at the beginning of the new century and in the wake of his presence in the city, an event that resonates in the works of a number of artists active in the city in the same years as Masolino, or immediately after. This is the theme of the fourth section of the exhibition (which actually begins on the wall opposite the one on which Masolino’s works have been arranged), opened by Lorenzo Monaco’s other triptych from the Museo della Collegiata, with a slightly later chronology than the one for San Donnino, and hypotheses about its provenance from the same church of Santo Stefano, as mentioned above. The first artist one encounters is Francesco d’Antonio di Bartolomeo, a collaborator on a few occasions with Masolino, and the author of some works in which the language of his colleague is interpreted in a more rubicund and light-hearted key, as can be seen in the Madonna della cintola di Loppiano, a work capable of bypassing without too much fuss the lesson of Lorenzo Monaco in which Francesco d’Antonio was trained. More composed and measured, however, is one of the leading figures of the time, Bicci di Lorenzo, who moreover also worked as a fresco painter in the church of Santo Stefano: the Madonna and Child Enthroned and Simone Guiducci da Spicchio, accompanied by a compartment that was part of the same polyptych painted for the collegiate church of Empoli, is one of his best works (indeed, for a large part of the critics we witness here the pinnacle of his entire career), and while lingering on late Gothic veins it shows that he already knew how to look to the Masaccesque spatiality of the Triptych of San Giovenale, a masterpiece in regard to which he should not have remained insensitive. And if a painter such as Giovanni Toscani remains proudly late Gothic, others, such as Paolo di Stefano Badaloni, known as Paolo Schiavo, and Borghese di Pietro, on the contrary try to push forward, albeit within the limits of their entirely vernacular lexicon. However, Paolo Schiavo, with his Crucifix, shows himself to be an artist capable of some elegance mindful of Masolino’s lesson, while more daring and coarse is the eloquence of Borghese di Pietro, who was nevertheless fascinated by Masolino and especially by Masaccio of the Carmine polyptych in Pisa.

Returning to the work around which much of the exhibition revolves, namely Masolino’s Christ in Pity , on the occasion of the exhibition it was decided to advance its chronology a little from the traditional 1424: not by much, just a few months, enough to shift its execution to the last months of that year, or to 1425, that is, when Masolino and Masaccio had already begun to organize the work at the Brancacci Chapel. This shift, which might suggest that Masolino returned to Empoli when Cappella Brancacci was started, is motivated by the substantial novelty of the Christ in Pieta (admittedly, little compared to what Masaccio was painting and had painted, but it all has to be weighed against what Masolino had produced up to that time), especially when one considers the fresco of the Baptistery with the Madonna that Masolino painted in the sacristy of the church of Santo Stefano: the comparison in the same location thus allows us to appreciate the forward momentum of the Pietà, justifiable perhaps by a more delayed execution. The last two sections of the exhibition are devoted precisely to two fresco enterprises: the earlier one by Gherardo Starnina in the chapel of the Annunziata, a few fragments of which remain (some of the saints in the access sub-arch: Moreover, it is thanks to these fragments that it has been possible to give a name to Gherardo Starnina, otherwise known earlier as the “Master of the Vispo Child,” because of his initial somewhat exuberant attitude, later diluted after his return from his trip to Spain), enriched with some works dating from the same turn of ’years, and Masolino’s in the chapel of the Cross (where, for the occasion, Lorenzo di Bicci’s Crucifixion , the altarpiece that stood here in ancient times, was returned from the Museo della Collegiata).

Even of Masolino’s frescoes, however, very little remains: they are mostly sinopites and a few fragments, which, if they cannot give us an idea of what the completed work must have looked like, nevertheless manage to suggest the originality of some solutions, such as theexpedient, in one of the scenes of the fresco cycle, of the false loggia under which the artist had arranged the figures, the presence of which can be guessed today just from some remnants of the architecture. Other details, however, reveal how Masolino had imagined a complex marked by a certain degree of illusionism, quite unusual for Tuscany at the time, just as unusual in these parts was the idea of setting the scenes continuously. Suppa believes that, for all these reasons, Masolino had to look to examples from northern Italy, especially Padua (from Altichiero to Giusto de’ Menabuoi via Guariento): the Empolese cycle is made up of paintings executed, writes Suppa, "at a time of full inventive freedom and rethinking of works seen as much in Tuscany as outside the region; that freedom which will happily return in the decorative campaigns of Castiglione Olona and which in Empoli is so passionate as to persuade Bicci di Lorenzo [in the frescoes of the right transept of Santo Stefano, ed.] to ignore for once the coherence between fake and real space and invent marble crustae that continue like wallpaper from one wall to another."

Finally, one last novelty should be noted, which concerns the fragment of fresco in the right transept, also by Masolino, located not far from the lunette decorating the access to the sacristy. The fragment has always been identified with a St. Ivo, but on the occasion of the exhibition Suppa proposes a different hypothesis: St. Ivo of Brittany, a jurist, is usually depicted seated, holding a scroll, a symbol of the causes upheld in defense of the weak, and with at his right side a small gathering of widows and the poor, his attendants. The saint depicted by Masolino holds what Suppa says appears to be a candle rather than a scroll, while to his right appears a group of young girls, smiling and well-dressed, with their hands crossed on their chests. More fitting, according to the scholar, might be the identification with the scene of the miracle of the Candlemas narrated by Jacopo da Varazze: the young girls would thus be the bidders who would have witnessed the appearance of Christ on the feast day, and here depicted waiting to receive the candle from the figure in the center, in the moments before the divine epiphany. Suppa does not explain why the church would have accommodated a depiction of Candlemas, a feast nevertheless quite popular in Tuscany at the time, but the hypothesis is certainly interesting and adds to the many identifications, more or less appropriate, that have been provided for this scene: Saint Julian has been mentioned, the name of Saint Sigismund has been advanced, and given the elements perhaps a Saint Ursula could also be thought of. The martyr typically wears a cloak lined with vaio, she is accompanied by a host of girls, that is, the companions martyred with her, and if one assumes that that white flap above the archway above the young women is what remains of a banner, then one might think that what she holds in her hand is her typical banner.

Leaving the church of Santo Stefano, also worth seeing is the panel with Saint Nicholas of Tolentino Protecting Empoli from the Plague, an in situ work by Bicci di Lorenzo from 1445, thus far removed from the period on which the exhibition focuses, and yet illustrative ofa phase of retreat to traditional modes that is among the trends occurring after Masolino’s arrival in Empoli, and which therefore perhaps deserved perhaps not inclusion in the visiting itinerary, but perhaps a small indication.

As anticipated, despite the lack of a few pieces (essentially the Bremen Madonna and the St. Anne Metterza), and despite a visiting itinerary challenged by a revisable layout, the public will find itself visiting an excellent exhibition. Empoli 1424. Masolino and the Dawn of the Renaissance is a quality exhibition that returns Masolino to his context and, it can be said, unties him from the cumbersome name of Masaccio. An exhibition that draws extraordinary strength from the fact that it was organized in Empoli, a center of no secondary importance in the geography of early fifteenth-century art, and that stands as a solid project of in-depth study of an artist, Masolino da Panicale, largely ignored by the “exhibition world,” if we want to call it that. An artist who, on the round anniversary of the most important year of his career, deserved a dense in-depth study that would reconstruct the first part of his career in an accomplished manner (it should be specified that it is on Masolino di Empoli that the review focuses: everything after the Brancacci Chapel was not made the subject of the exhibition). An irregular, enigmatic artist, constantly changing, always on the move: Empoli, however, is perhaps the city that more than any other lends itself to a vertical investigation of this significant protagonist of the early fifteenth century, of the fundamental years in which the gradual transition from late Gothic to Renaissance painting was accomplished. For, apart from Florence, perhaps no other city, at least in the present state of our knowledge, holds so many traces of the reflections Masolino must have made in those crucial months. And surely no other has a church where it is possible to see, just a few steps away, the before and the after, a Madonna of late Gothic sweetness and a fresco cycle, though reduced to a shadow, enlivened by brand new impulses.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.