Mark Manders, when writing with objects instead of words. What the Sandretto exhibition looks like

As a rule, we are accustomed to bring under the umbrella of conceptual art a varied catalog of artistic expressions in which instances related to the constructive process and speculative scheme that determine the work are predominant over the aesthetic and perceptual result. This artistic current, which developed after 1960 in the United States from Joseph Kosuth’s experiments with the logical and semiotic relations between image and word, aspired to liberate art from formal and material constraints by concentrating research on the stages of design and ideation. Throughout the twentieth century, this intent was inscribed in an already ongoing path of progressive erosion of aspects hitherto considered constitutive of the work (such as mimesis, perspective, emotional involvement, relationship to past visual culture or commercial value) culminating in the desire to disregard the work of art and, in its most radical outcomes, in the choice to renounce it altogether. On the basis of these premises, very different historicized experiences can be defined as “conceptual” but characterized by an unmistakable common denominator (such as Land Art, Arte Povera, Minimalism, Body Art, Narrative Art and other related trends), to which have been added in the following decades the productions of artists who, while being freed from the ’membership in a specific group, converged in their commitment to subsume in various combinations certain foundational aspects of such seminal experiences, such as chromatic and geometric rigor, the use of objects inferred from everyday life or the inclusion of the written word in the work. Things have become more complicated with the transdisciplinary syncretism of the narrow contemporary period, in which an arrangement of a prima facie conceptual mold, according to these parameters, is no longer an unequivocal expression of the search for an ideal and theoretical order, but can also be the result of a purely aesthetic reactivation of the languages through which such an aspiration had in the past found a hypothesis of visible form.

In the boundless panorama of contemporary conceptual art, in recent times dominated by the massive irruption of data, processes and suggestions coming from the digital universe, the work of Mark Manders (born in Volkel, Holland, in 1968, lives and works in Ronse, Belgium) stands out as the protagonist of the exhibition Silent Studio curated by Bernardo Follini at the Fondazione Sandretto Re Rebaudengo in Turin and open until March 16, 2025. The exhibition takes the form of a wide-ranging anthology dedicated to the more than 30-year career of an artist with whom the foundation has built a very solid relationship over the years, which began with his participation in the collective Guarene Arte 97, on the occasion of which, in 1997, he received the Regione Piemonte Prize for the project Self-Portrait as a Building. And it is precisely this cycle, which is still in progress, that is the focus of this further Turin stage, which finds its ideal setting in the city headquarters of Sandretto Re Rebaudengo, a white, neutral and linear building of almost 4,000 square meters dedicated to temporary exhibitions of contemporary art, awarded to the foundation in 2022 following a European call for proposals.

The idea behind this research, which the artist has been pursuing since 1986, is to write with objects instead of words, using them as the structural materials of a fictional narrative building composed in power of all the words in the Oxford English Dictionary and for this reason predisposed to reformulate itself differently with each new exhibition occasion. For Manders, this building is based on the idea that an architecture can represent a self-portrait, allowing the viewer to enter that recondite mental space where the logic and subconscious drives of its creator meet, but at the same time, once materialized, it transcends the individual sphere to become collective in the interpretive contributions of the audience engaged in decoding it. In line with this proposition, the initial idea of the exhibition is to construct a new self-portrait by being guided by the minimalist architecture of the foundation, much like the artist’s studio in Belgium to which, ultimately, his settings always refer. As in every exhibition, the absence of the artist is the propulsive core of the set-up, as here too the narrative organization underlying the visit involves the audience entering what is almost immediately guessed to be a place of work, offered to the gaze immediately after the inhabitant has left it.

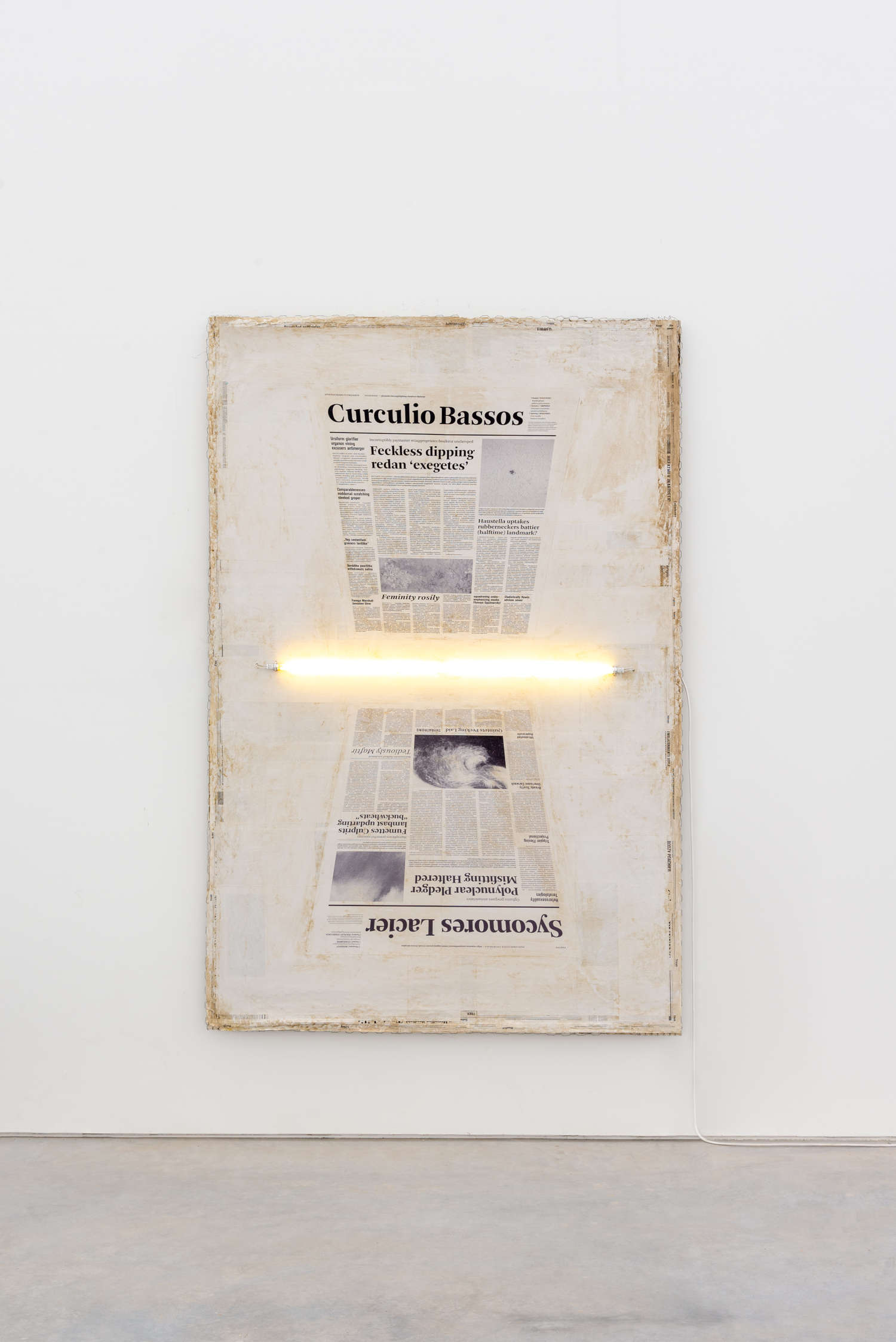

The path opens with a kind of antechamber in which Manders’ personal glossary, which will appear in the main room in a syntactic environmental arrangement, materializes paratactically. We first encounter the assemblage Perspective Study (with All Exhisting Words), 2005-2025, in which the mirrored reversed image of what would appear to be a photographic reproduction of a newspaper mounted on canvas has as its pivot a switched-off neon light, disconnected from the socket. This is an emblematic work, part of a large cycle entitled Room with All Exhisting Words, consisting of a series of ten fictitious, perfectly verisimilitude newspapers, in whose pages taken as a whole appear without repetition all the words of the English vocabulary just mentioned placed in random order. The artist has on several occasions stated the autobiographical origin of the series (and of his poetics tout court), rooted in his youthful desire to become a novelist, which led him first to draw up a “planimetry” of all the writing material in his possession, and then to the choice of using objects as vocabulary in order to pretend to have all possible words at his disposal, thus becoming the author of an imaginary novel as a visual artist. Going into the details of the work in the exhibition, then, we understand that although the paper, layout and typographic setting are entirely credible, the text is not configured as a readable chronicle, but as a nonsensical poetic composition that introduces the theme of the relationship between words, objects and sculptures. At the same time, the fact that the neon is off although working introduces the suspicion that the alluded to environment is not an exhibition space, but a laboratory in which what the artist has made appears in a crystallized dimension, another crucial aspect being that he is used to working for very long periods (even decades) on the same works. The title Perspective study, on the other hand, is a reference to the studies of perspective with which, from the Renaissance onward, all academically trained artists had to deal (in this case, the reproduction of the object-journal tilted with respect to the pictorial plane), but perhaps also the ciphered suggestion to “put the works in perspective” in order to grasp their internal syntax and mutual relationships.

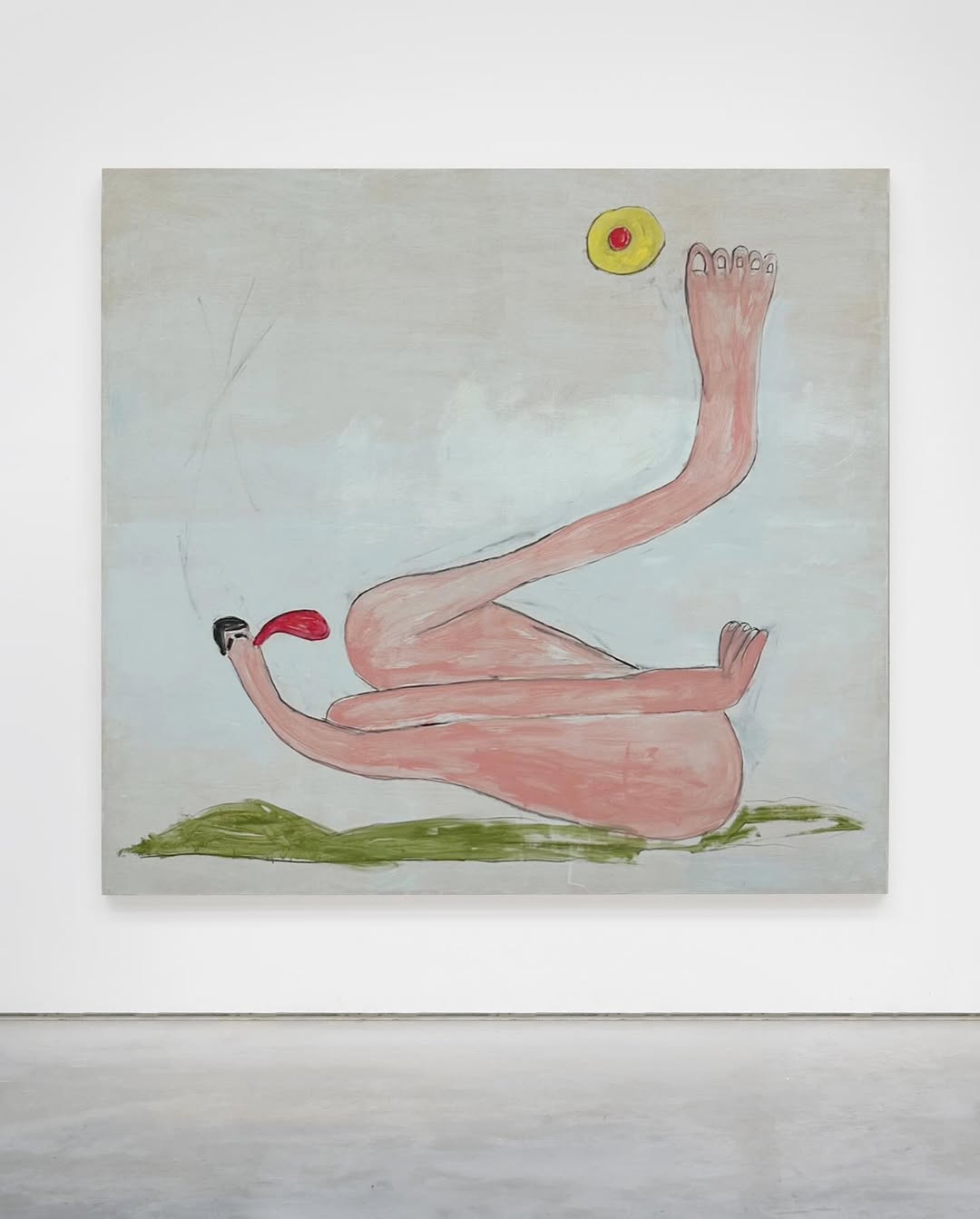

The second work we encounter is Skiapod 57, 2005-2024, an acrylic on wood in which a strange, boneless, disproportionate anthropomorphic figure appears lying on its back, with a large red tongue stretched outward and a single leg ending in an oversized foot used as a sunshade umbrella. The Jackpod is another keystone in Manders’ creative thinking, a supposed mythological creature of his own invention born out of the appropriation of a dictionary word “in which no one is interested,” implemented to demonstrate how it is possible to build an entire world from a single word. The artist (on his website) has also dedicated a Wikipedia page to this character with a mixture of real and fallacious information, presenting it as a recurrence in various world cultures since ancient Greek times.

This philological narrative contaminated with additional fallacious information is corroborated by a series of fake works in the style of other artists, such as Philip Guston or Maria Lassnig, depicting the Jackal to the point of making it impossible to discern the real from the fake. The world then understood as rewritable history, but also highly misunderstandable, a demonstration for the artist of the concomitant strength and weakness of the human mind. We begin to look around with growing suspicion when we realize that the other elements displayed in the room (modernist-style furniture, small works by the artist placed inside vitrines on par with some enigmatic painter’s tools for holding pencil or projecting shadow) set our presence in an ambiguous pseudo-domestic setting. In fact, as we enter this waiting room, we have already been trapped inside the work because everything we see (as in every Manders exhibition) was conceived, designed and produced by him, including the furniture and display structures. And, finally, an example of Manders’ figurative sculpture, a sketched clay silhouette with a stylized Etruscan face protected by gauze and left to rest poised on a chair upholstered with newspapers, perhaps the same one the artist was sitting on as he modeled it. The sculpture, beyond ambiguous in its appearance at once malleably moist and close to crumbling, is armless and placed in a suspended time in which archaeology and preliminary study collide. The agnition occurs when, upon reading the captions, we discover that clay is not their constituent material, but bronze, subsequently camouflaged through pictorial interventions so as to simulate the effect of clay, suddenly bringing the work closer to the painting side in spite of its ostentatious chromatic negligence.

We are now perceptively and rationally astute enough to enter the next room, the heart of the exhibition-studio where these suggestions are composed into a grandiose environmental symphony. To the main room we are introduced on the threshold by the small work exhibited in 1997 in Guarene, Fox/Mouse/Belt, 1992, depicting a fox and a mouse flattened to the ground and fastened to each other by a real leather belt, inspired by the desire to create a work from the three words in the title. Inevitably, thinking about the mode of linking language and artwork of which this work is a consequence, one supposes an unconscious foreshadowing of the prompts on which the collaboration between humans and AI is based today.

Then Manders’ imagery expands and deflagrates into a sumptuous construction site punctuated by impalpable wings of opaque cellophane, where some of his iconic large sculptures rest on rudimentary work tables as if they had been abandoned in progress and await the artist’s return to be completed. These mysterious busts with imperturbable faces devoid of individual connotations, in which the profile of the neck and shoulders traces the ideal figure of the human subjects painted by Piero Della Francesca, appear sectioned from tablets wedged into what looks like fresh clay (in truth camouflaged bronze), an ambivalent allusion to the artist’s studies of color and geometry and the (in this case fictitious) technical necessity of portioning out clay sculptures of such dimensions during modeling. All the other elements that appear scattered in the space as installation materials, including the rope to which a giant head is anchored, the accumulations of raw material in the corners, or an anonymous stool, are also placed according to a definite rhythmic score and, ça va sans dire, are hyper-realistic bronze reproductions of the aforementioned objects. The only real clay, however, is the dust with which the floor is sprinkled, which constitutes yet another significant gap in this environmental work, being the waste of the molds molded by the artist for the casting of the sculptures.

The tour concludes with another inescapable aspect of the studio, a sequence of drawings hung by clothespins from a thread (as is really the case in Manders’ workshop in Belgium) that runs all along the wall opposite the entrance, outside the area circumscribed by cellophane curtains. Although references to the works on display can be recognized in many of them, they are not necessarily design drafts of works to come, but rather thoughts crystallized by the graphic mark and allowed to decant on the surface of the paper, as happens with sculptures in three-dimensional space or words in mental space. Like the other elements that make up the exhibition, the drawings also take the form of “portraits,” since they derive their raison d’être from the need to explicate how the artist thinks and acts through circumstantial means, leaving the visitor with the burden (and above all, the pleasure) of tuning in to his logics in order to explore to the fullest extent the labyrinthine consequences.

In the light of these reflections, it becomes clear how, although at first glance the formalization of Manders’ research seems to derive from an aestheticizing and scenographic inspiration, in reality it is firmly anchored in the conceptual sphere, of which it constitutes a highly personal and striking declination. Everything is orchestrated to instill doubt and make us confront the limits of our cognition, and the reciprocal relationships between the various elements are governed, as in the best tradition, by a structure of random but unbreakable rules. In this astonishing invention, which we might describe as “conceptual illusionism,” we also find harmonized and co-present (just under the skin of the visible) the main features of historical conceptualism mentioned at thebeginning, such as the centrality of the written text and the process, compositional minimalism, and the semantic importance of the object, further proving the coherence, logical hold, and relevance of this more than thirty-year research.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.