In the last twenty years alone, nine exhibitions dedicated in various ways to Vasily Kandinsky have been counted in Italy, without mentioning the exhibition occasions built with his multiples, or those where the name of the great abstractionist was included in the title of reviews investigating a period or an artistic movement, with the usual formula “from this to that.” An artist with a solid and lasting exhibition fortune, then. A fortune that can be explained by the popularity of his works with the general public: his name, obviously well known even outside the circle of enthusiasts, can be compared, in terms of attractiveness, to that of the Impressionists, Frida Kahlo, Chagall, just to limit ourselves to artists that it is difficult not to find in the annual schedules of our museums. To frame, then, the tenth Italian exhibition on Kandinsky in the last two decades, the one that Paolo Bolpagni and Evgenija Petrova have set up in the halls of Palazzo Roverella in Rovigo (the title, of surprising simplicity, is Kandinsky. The Work 1900-1940), one cannot disregard contextualizing the Venetian exhibition in the framework of the history of recent exhibitions on Kandinsky: it is a necessary operation to identify similarities and novelties.

Scanning the exhibition history of Kandinsky in Italy, one will notice that several exhibitions have been built with nuclei of works from a single collection. Going back to 2003, this was the case for Kandinsky and the Abstract Adventure, which exhibited more than a hundred works from the Guggenheim Foundation at the Villa Manin di Passariano. It was the same for Kandinsky and the Russian Soul, held between 2004 and 2005 at the Achille Forti Gallery of Modern Art in Verona: the works were on loan en bloc from the Russian State Museum in St. Petersburg, and more than a monographic exhibition on Kandinsky, despite the title, it was a journey through the history of Russian art from the end of the second half of the nineteenth century to the 1930s. More surgical was Wassily Kandinsky and Abstractionism in Italy 1930-1950 in 2007, the exhibition that Milan, sixty years after the last exhibition in the city on Kandinsky, organized to investigate the reflections of the Moscow artist’s lesson on Italian abstractionists. Small and refined was the 2012 MAR exhibition in Aosta, Wassily Kandinsky and Abstract Art between Italy and France: Alberto Fiz gathered about forty works by French and Italian artists contemporary with Kandinsky to explore, again, how the Russian master’s legacy had spread to our latitudes. The exhibition that comes closest to the one in Rovigo (it also benefited from the same curator, Evgenija Petrova) is Wassily Kandinsky. From Russia to Europe (in Pisa, Palazzo Blu, between 2012 and 2013), which examined the first two decades of the artist’s career, with works from the Russian State Museum and other institutions. Back in Milan, between 2013 and 2014, Wassily Kandinsky prepared an itinerary from his beginnings to the 1930s, which made use only of works from the Centre Pompidou. Again Evgenija Petrova curated, in 2014, the Wassily Kandinsky exhibition Lartist as Shaman, at the Centro Arca in Vercelli, with some 20 works from eight Russian museums, along with works by other avant-gardists, to bring to life a focus on the years between 1901 and 1922, that is, from the start of his career until his final departure from Russia, the same period examined by the Pisan exhibition the year before. Dedicated to specific themes were the last two exhibitions: Kandinsky, the wandering knight, at Mudec in 2017, curated by Silvia Burini, focused on Kandinsky’s path towards abstraction, while Kandinsky->Cage: Music and Spiritual in Art, at Palazzo Magnani, Reggio Emilia, between 2017 and 2018, was an in-depth study, curated by Martina Mazzotta, on the relations between painting and music.

Retracing the steps that have accompanied the fortunes of Kandinsky in Italy over the last twenty years, the novelty of Bolpagni and Petrova’s project is already clear. Besides being one of the few (another note of merit) that in all the texts adopts the scientific transcription from Cyrillic instead of the Anglo-Saxon one that has always been popular, it has also proved to be the most varied and complete, with a fresh and engaging layout, and clear apparatus (despite the difficulty inherent in any exhibition on Kandinsky: the risk of exposing oneself to excessive trivialization on the one hand, and on the other, the danger of ordering an overly ponderous and tiring visiting itinerary), and supported by a seemingly simple scholarly project liable to fall into déjà-vu (“grasping the unitary arc of the artist’s path by identifying the constants that, from the early twentieth century until the end , innervate his highly personal way of painting,” the curators had declared before the exhibition opened), but punctual and well grounded, and supported by a selection that avoids pedantry and that, for each of the phases of Kandinsky’s art, offers the public a small but decidedly significant nucleus of works. Some foundational works are missing, such as the First Abstract Watercolor from the Pompidou orImpression III (Concert) from the Lenbachhaus in Munich, but the spirit of certain cornerstones is nevertheless well evoked by the presence of quality works.

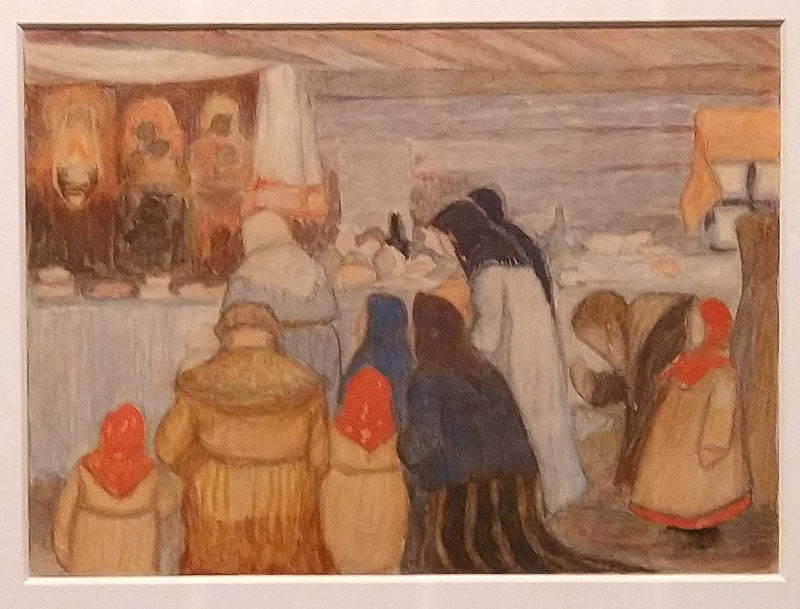

Although, it has been mentioned, everyone has heard of Kandinsky at least once, not so well known, however, is the fact that his career began very late, at exactly 30 years of age, that is, at an age when at that time he was considered a made man, with a definite and solid position in society: in 1896, after a law degree and a rising university career (he was a researcher), Kandinsky decided to leave his job and his country to pursue the dream of art, which he had been cultivating since childhood as an amateur. In his 1913 paper, Glances at the Past, published in the wake of the controversy surrounding his early abstract works (and offered in full as an appendix in the exhibition catalog), the painter had traced the stages of his initiation into art. Nine were the founding moments, summarized with abundance in Philippe Sers’ essay in the catalog: central, in 1886, the contemplation of a sunset over Moscow, dazzling the encounter with Monet’s Haystacks in 1896 during an exhibition on the Impressionists in the Russian capital, revealing the vision of the colors of the peasant houses in the Vologda oblast, five hundred kilometers north of Moscow, visited during a month-long work trip, at a time when the artist was still a researcher (he was commissioned to travel to that remote region to study the law of the people who lived there). It is from this journey that the exhibition’s narrative begins: everyday objects, small toys, folk prints(lubki), icons (of which the painter was also a collector), textiles, and pieces of handicrafts welcome the public to recreate the atmosphere that must have accompanied Kandinsky on his journey through the countryside of the Vologda region, and that so inspired him, since his notebooks are filled with notes on what he saw. The Rovigo exhibition offers the rare opportunity to admire a work that can be placed in a period very close to Kandinsky’s decision to devote himself exclusively to art: it is titled At Easter and can be found immediately at the opening, next to a slightly later work, Domenica (Old Russia), on loan from the Boijmans van Beunigen Museum in Rotterdam. The first painting, in a style close to that of the Nabis, conveys from the outset the sense of spirituality that would always accompany Kandinsky’s art (“the most profound conviction that in life, as in art,” writes Evgenija Petrova, “the soul, the spiritual, the sensibility should take precedence over materiality shaped his conception of the world”), while the second, which finds its references in the pointillism of French artists such as Léo Gausson and Théo van Rysselberghe, reveals the artist’s passion for the customs and traditions of the peoples of Russia, another interest that would continue to permeate his painting.

Here, then, are the experiences of the early Kandinsky, who, having finished his career as a researcher in law, left Russia and moved to Munich to further his study of painting, first with Anton Ažbe and then with Franz von Stuck. An interest in tradition, fairy tales, and Russian legends is at the heart of his painting, as evidenced by the Xylographies album published in 1909 (but actually executed two years earlier), a collection of fairy motifs, characters, and small landscapes where formal simplification is a prelude to the move toward abstractionism, with the figures now reduced to their essentials, hinting that shortly thereafter the sensations experienced in the face of reality would be transformed into notes of color (Kandinsky himself, after all, likened etching to music, since a woodcut presupposed that the artist would bring out the “inner sound” of the subjects). Also of supreme interest are a number of landscapes, painted on plywood boards, which offer further evidence of the early Kandinsky, a painter who looked with keen interest at post-impressionist painting. In the first two rooms two main themes of the exhibition have already taken shape, namely the spiritual and the interest in folk arts: the basic idea of the exhibition, after all, is first of all to investigate the sources of Kandinsky’s attitude towards painting.

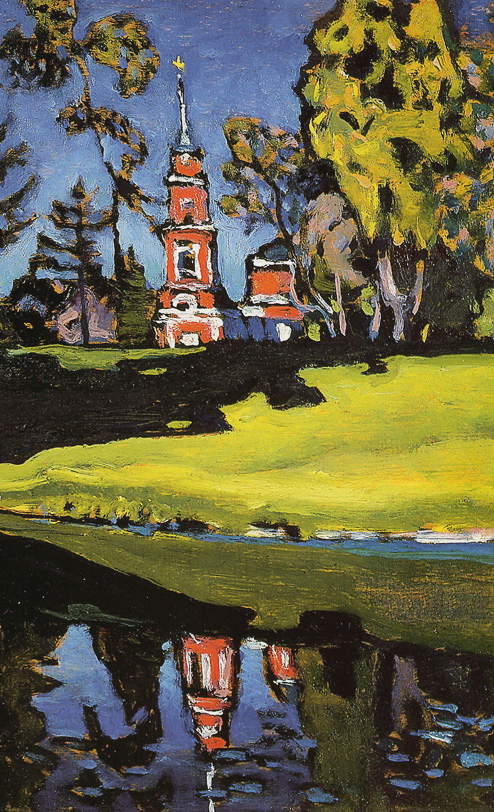

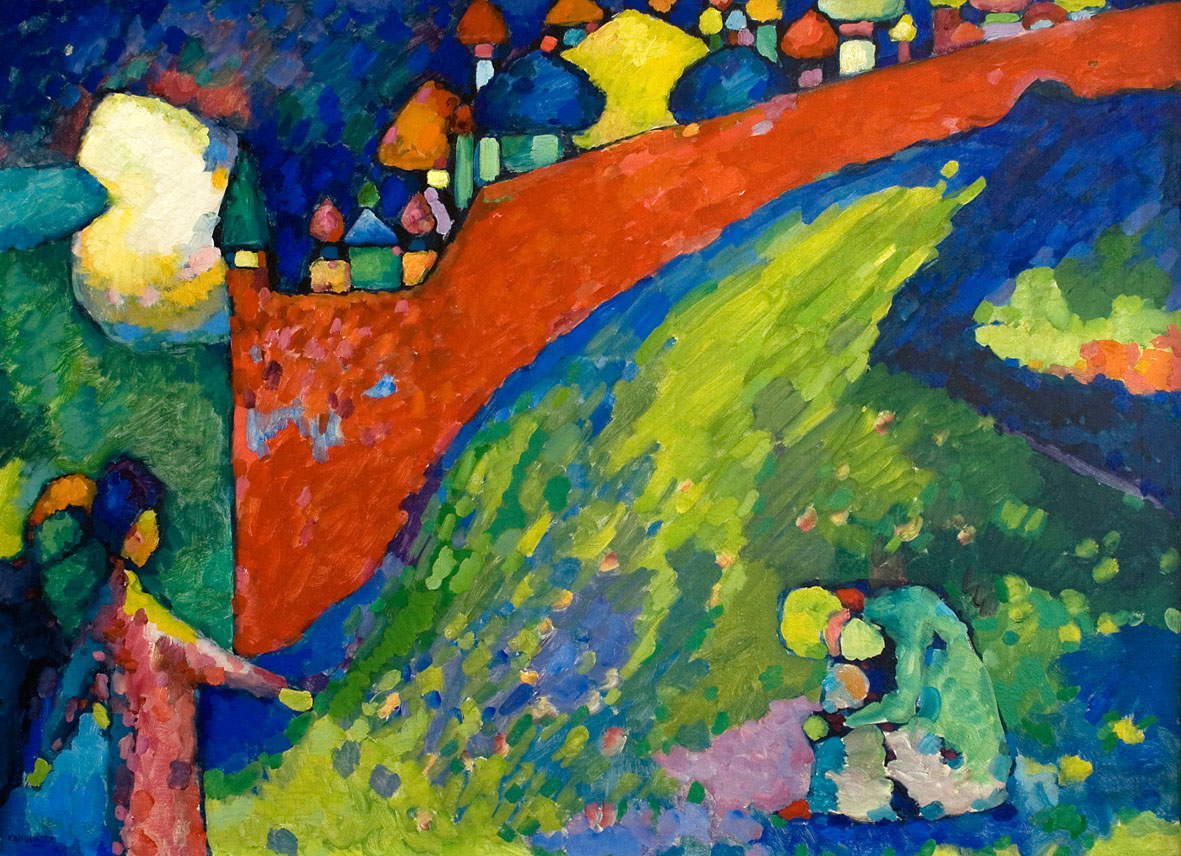

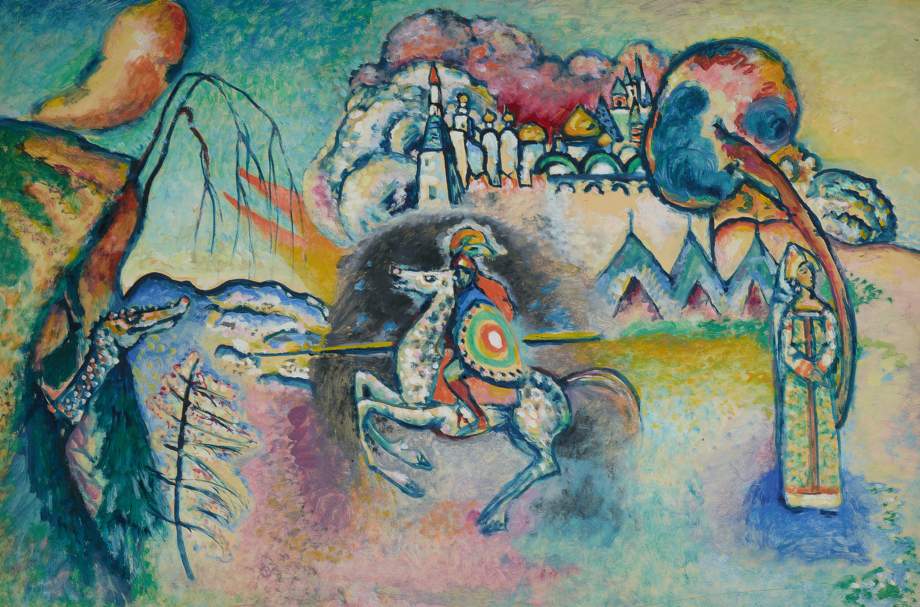

The next section of the review investigates the period of Murnau and the “Blue Rider”(Der Blaue Reiter). In 1908, after he began to reap his first successes (in 1904 he also exhibited at the Salon d’Automne in Paris), he bought a house in the small town of Murnau, Bavaria, and in the same turn of years he got to know and associate with Gabriele Münter, who was also his life partner for some time. Instead, the start of the Blue Rider group’s activity dates back to 1911, with the first exhibition, which opened on December 18 of that year, at the Thannhauser Gallery in Munich. There are only three landscapes from the Murnau period in the exhibition, but all of them are relevant in communicating to the public the developments of Kandinsky’s art, which arrives at a new view, an interior view, which transfigures a state of mind in the landscape, although with different means than the Symbolists, the painters of the paysage-état d’âme, had done some 20 years earlier: Kandinsky expresses himself through full backgrounds of pure color, such as the large red blade we see in the center of Red Wall. Destiny, a 1909 work that arrives from the State Art Gallery “Dogadin” in Astrakhan, a fundamental painting that, wrote the art historian and Russian avant-garde expert John Bowlt, constituted a sort of response to the shapes of Russian church domes, which are admired in the background of the painting, integrating expressionism, Fauvism and neo-expressionism. By contrast, blue predominates in Murnau. Summer Landscape, where bright colors and curved lines communicate a feeling of gladness, of good disposition. It was, after all, an “inner necessity” (a principle that, as will be seen later, underlies Kandinsky’s art) that had led to the birth of the Der Blaue Reiter group, as attested by the original typescript, the four sheets of which are all exhibited in Rovigo, that Kandinsky and Franz Marc had prepared to present their programmatic Almanac, a collection of works and writings by the artists of the movement and those who inspired them. “At the time of the pseudo-flowering season, of the great triumph of materialism in the century just ended,” Kandinsky wrote, “the first new elements of the spiritual atmosphere were born, almost unnoticed, which nourished and will nourish the flourishing of the Spiritual.” On display is a painting that has become the poster child for this season, the celebrated Knight from the Tret’jakov Gallery in the exhibition, actually a St. George hurling his spear at the dragon to save the princess, dressed in traditional clothing: a sort of alter ego of the artist, St. George is the hero of Kandinsky’s cathartic message, the metaphor of this “saving mission of the knight and the shaman,” to use the words of Jolanda Nigro Covre, an image that the artist draws from the traditional repertoire of his homeland and loads with unprecedented meanings. Closing the circle, in the room, are the works of Gabriele Münter, Marianne von Werefkin, Alexej von Jawlensky and Paul Klee to evoke, even if only partially, the spirit that hovered over that highly innovative group of artists.

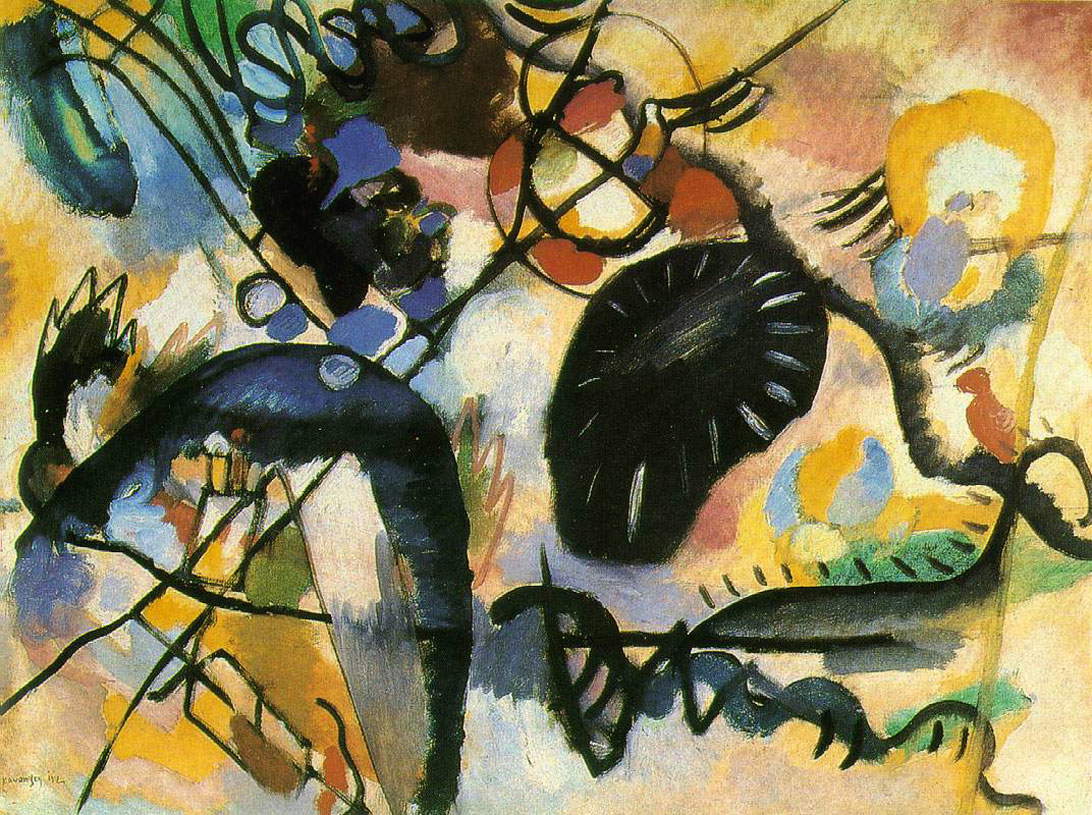

The path toward abstractionism, firmly achieved between 1910 and 1912, is the subject of the following section, which exhibits four works executed in the same turn of the year to give the audience an account of the process leading toward increasing stylization, which starts from an impression (a sortie on the lake, for example: this is the case with A Boat Trip, another work on loan from the Tret’jakov Gallery where the landscape is a score of dark tones that offer the suggestion of water, sky and shoreline, with quick white notes in which we recognize the silhouettes of boats with rowers) and leads to a painting in which colors and shapes are freed from any representational function: they serve to evoke feelings, sounds, moods, moving from the symphony of Nonobjective, from the “Kovalenko” Regional Art Museum in Krasnodar, to the strong contrasts between opposing feelings evoked by Black Spot I, another 1912 work from the Russian State Museum in St. Petersburg. The Rovigo exhibition constantly seeks to trace the origins of Kandinsky’s inspiration, and in this process music assumes a decisive role, as indeed is known to anyone who has delved into the work of the Russian abstractionist. Music, Kandinsky wrote in the famous essay The Spiritual in Art given to print in December 1911, is an art form that “already for some centuries has not been using its means to imitate natural phenomena, but to express the psychic life of the artist,” and consequently, writes curator Bolpagni, “may serve as a model for the other arts, especially painting, which will have precisely to free itself from mimesis and respond to the principle of inner necessity.” Every sensation corresponds to a color, to a shape, to a sound, according to links and relations established by this “inner necessity”: color, in particular, “is a medium that enables direct influence on the soul,” Kandinsky wrote. “The color is the key, the eye is the gavel, the soul is the piano with many strings. The artist is the hand that by touching this or that key, appropriately sets the human soul in vibration. Therefore, it is clear that the harmony of colors must be based only on the principle of the right stimulation of the human soul. This basis must be designated the principle of inner necessity.”

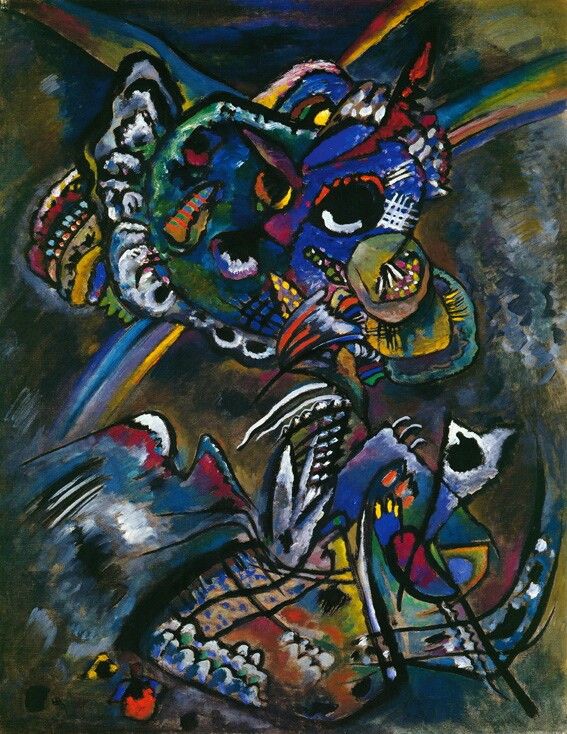

Decisive was his encounter with the music of the Austrian composer Arnold Schönberg: Kandinsky first attended the performance of one of his concerts on January 2, 1911, and the experience was so fulminating that he wrote to Schönberg and established a lasting friendship with him (the exhibition does not overlook this bond, evoked also by the presence of some of Schönberg’s works, which he enjoyed painting). Just as Schoenberg, with his dissonances, had subverted the rules of classical music, Kandinsky set out to do the same with his improvisations, with his compositions. In 1914, upon his return to Russia, the artist spent several years promoting the novelties of his art in his own country as well, and the exhibition devotes an entire room to what the artist produced between the year of his return and 1922, the year in which Kandinsky, ostracized by the Russian cultural milieu, which was more inclined to pander to the art of the Constructivists as it was more in line with the wishes of the regime, decided to leave his homeland for good and return to Germany. During this period, Kandinsky worked primarily on “compositions,” deeming important his stay in Moscow, which, writes Silvia Burini in her catalog essay, for the artist “is always connected with a maternal and enveloping feeling, on the one hand, but also, on the other, turns out to be the source of a kind of dissonant harmony.” The “contradictory characteristics” (this is the expression used by Kandinsky in Glances at the Past) of the Russian capital are at the basis of many paintings that seek to express these sensations, going from the swirl of the Composition of the Museum of Local Traditions in Thumen’, with the circular course found in several works of this period, as if to evoke the security of an embrace, to the explosion on a dark background of the Twilight of the Russian State Museum, a work of 1917 that evokes the sensations felt when faced with the spectacle of sunset. Among the pinnacles of Kandinsky’s “musical” production of these years it is also possible to include a work such as the Blue Ridge, a kind of inner landscape constructed with very contrasting and dissonant notes, with yellow and red notes, bright and vivid, trying to wedge themselves onto a solemn blue score, giving rise to a profound antithesis. A small room is instead dedicated to Kandinsky’s refined and amusing production on glass from 1918: small olî dedicated to Russian fairy tales (“bagatelles,” Bolpagni and Petrova call them in the catalog), which mark a return to figurativism (or, even better, should perhaps be understood as a commitment to continue the deepening of an interest that never abandoned Kandinsky) and which transport the viewer into a dreamlike, almost childlike world. This is an important presence in the exhibition because it testifies to how versatile and far from monolithic was the path of Kandinsky, an artist who often liked to change direction.

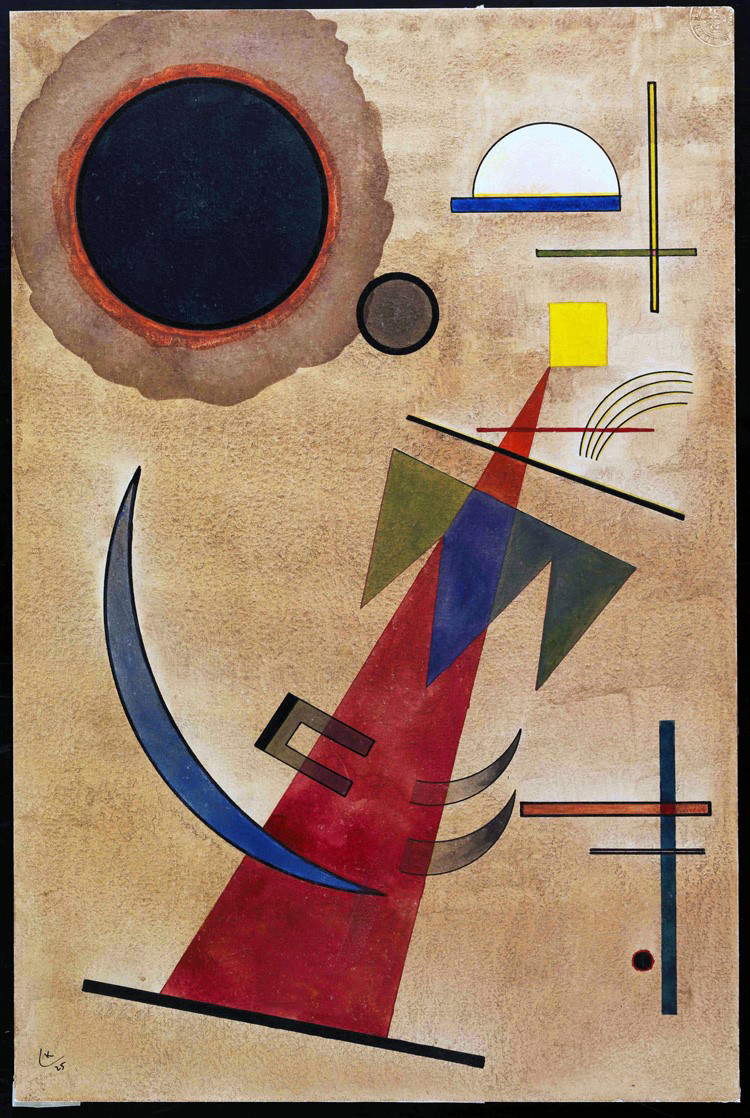

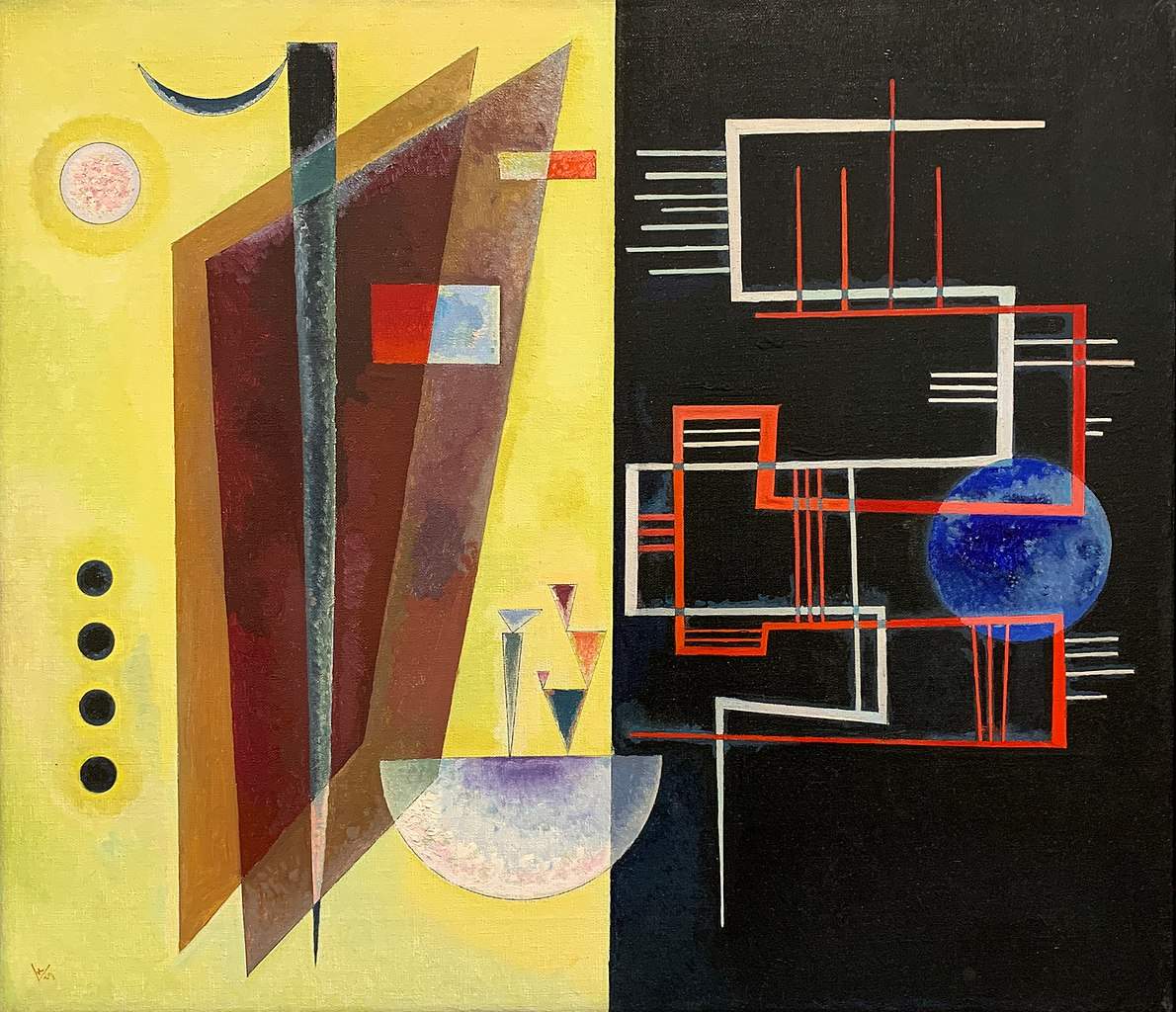

Shortly before he left Russia, Kandinsky, in 1920, painted On White I, a work that anticipates some trends that will be characteristic of the later period, investigated in the last two rooms of the exhibition in Rovigo: the tendency toward geometrization (a chessboard also appears), the use of cold tones, light scores, the extensive use of white (white, Kandinsky wrote in The Spiritual in Art, “is like a symbol of a world in which all colors, as material properties and substances, have disappeared. This world is so far above us that we cannot perceive any sound of it. From there comes a great silence which, materially represented, presents itself to us as a cold insurmountable, indestructible wall, which extends to infinity [...]. It is a silence that is not dead, but rich in possibility.”). The importance accorded to pure forms (the circle, the line, the point), among which it is possible to glimpse the shadow of Malevič, is evident in the paintings executed after his return to Germany: Kandinsky moved there in 1922 to teach at the Bauhaus, Weimar. Exemplary of this phase are works such as Red in a pointed form, one of the artist’s rare works preserved in Italian collections (the watercolor in question is housed at the Mart in Rovereto), or even Internal Alliance at the Albertina in Vienna, which insists on the rigid distinction between opposites, to the sinuous and playful forms of the Red Knot at the Fondation Maeght. This is perhaps Kandinsky’s least known period, the one that marks the turn toward geometric abstraction, rejected in the Munich years, Nigro Covre argues, because it would have otherwise “limited the infinite freedom of forms and numerical combinations.” the interest in the spiritual, alien to the poetics of Malevič, does not, however, depart from Kandinsky’s painting, and geometric abstraction, Nigro Covre writes, is nothing more than “a development of lyrical abstraction,” where the arrangement of forms, their approaches and clashes, the agreements and disagreements with colors, the tensions between the elements that organize the composition are the most obvious ways in which Kandinsky continues to express his “inner necessity.”

Closing the exhibition is a room that presents the public with a selection of plates from the album Klänge (“Sounds”) published in 1913, an inescapable stage in the artist’s journey: a set of etchings that Kandinsky had published with the intention of retracing the origins of his journey toward abstractionism, toward the “spiritual in art,” a kind of synthesis of his art up to that point, where the artist, writes Philippe Sers, “puts into artistic form the dialectic between inspirations and occasions on the personal level” and where he “mulls over his own spiritual intuitions with respect to the events of his life by subjecting them to the process of synthetic composition, an exercise in creative wisdom.” A leave-taking to return to the main problem of the exhibition: the origins of the ideas that moved Kandinsky’s hand and mind.

The question, indeed, is beyond complex, and the album Klänge is but part of the answer, for which it is necessary to traverse much of the artist’s production, written and painted. It is also interesting here to take up the words of Sers, who identifies at least three sources that lie at the origin of Kandinsky’s “necessity,” that is, that attempt to establish contact with the soul. The first source is the personality of the artist himself, who like every human being is called to a mission in the world: to fulfill his own, the artist makes use of his works. The second source, Sers writes, is the “contribution or language of the artist’s age and cultural environment, of his nation,” the “style in its inner value,” and finally the third level is the “pure and eternal inspiration of art, that is, the message of art in what is universal.” One of the reasons for the interest of the Palazzo Roverella exhibition lies in its timely investigation of these aspects with an itinerary that spans the entire span of Kandinsky’s career and with a selection that, by pivoting to a few key works, accurately summarizes Kandinsky’s art and that is not always given to see in exhibitions on the Russian artist. And the one in Rovigo is certainly one of the best exhibitions on Kandinsky that has been seen in recent years, the most comprehensive among those the public has had the opportunity to see in Italy. The exhibition is supported by a dense catalog, where Andrea Gottdang’s full-bodied 2003 essay Vasily Kandinsky by Andrea Gottdang has also been republished: it is a pity that it lacks the individual works’ files (as is now unfortunately typical of catalogs of exhibitions on nineteenth- and twentieth-century art), and above all a bibliography, which would have been very useful (there is no need to remark on how inconvenient it is to have to search for titles among the notes of the essays).

Finally, there is another element that runs under the radar throughout the exhibition: within what cultural references should Vasily Kandinsky be included? It is reductive to simply call him a “Russian artist,” as we often tend to do by convention. He himself, in his Glimpses into the Past, tells of his “great love” for music, “for Russian literature, and for the profound nature of the Russian people,” just as he tells of his passion, since childhood, for German fairy tales (and he always spoke German: his maternal grandmother came from Germany), and at the same time he remembers trips to Italy and Germany with his parents, the beauty of Moscow, the decisive mark on his idea of being a painter that Wagner’s Lohengrin and Monet’s Haystacks had on him, and then again the paintings of Repin and Rembrandt, the music of Liszt. After that would come the Munich experience, the French experience, and teaching at the Bauhaus. While it is undeniable that his art is deeply rooted in Russian culture, equally fundamental was the contribution of the most varied experiences and travels and sojourns in different European countries: the many who have called him, and continue to call him, a “cosmopolitan Russian” are probably right. Born in Russia, raised in the Ukraine, long active in Germany and France, an artist who spoke several languages, uninterested in politics but sidelined by the Soviet regime first and hostile to the Nazi regime later (when the Bauhaus was closed by political decision, Kandinsky could nonetheless comment sarcastically by noting that for two more years the school, by a commitment made by the Dessau administration, would continue to receive subsidies, while “we stand outside of political passions and will no longer depend on their imbecilities.”), in contact with some of the most eminent cultural figures of his time, Kandinsky was one of the most refined and least pigeonholed intellectuals of his time, who applied his attitude as a researcher to art as well. To arrive at outcomes that changed the fate of art history.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.