Like a trip to the French Midi: what the Matisse exhibition in Mestre is like.

Constructed like a journey is the fine exhibition that the MUVE-Candiani Cultural Center has dedicated to Henri Matisse, a journey to that “Midi” in which, as art historian André Chastel guessed, “French modern art” was born, which in that part of the century meant modern art tout court.

An itinerary, therefore, that starts with some views of the ports of the North, neuralgic both in Matisse’s biographical story and in the construction of his own visual culture, and goes on to discover the light of the Mediterranean in the company of equally extraordinary artists.

In fact, the exhibition opens with a room with an ironic title - Modernity Comes from the Sea - because, as exhibition curator Elisabetta Barisoni explains, "another modernity had been born in the North, that of Symbolism, and the one to which Matisse looks to at the beginning of his career having himself been born in Le Cateau-Cambrèsis and thus in northern France. His early paintings display a pastiness close to the manner, and palette, of Van Gogh’s Potato Eaters. He is in short still far from the chromatic accents for which he is famous and which are due to the later revelation of the Midi, with its golden light dissolving shadows."

The narrative of this moment of passage is entrusted to The Tree, a small but intense cartoon from February 1898-from the Centre Pompidou in Paris-that marks precisely the discovery of the Mediterranean during a trip to Corsica, where “everything shines, everything is light,” as Matisse himself wrote to his friend Albert Marquet, who is also in the exhibition with Bougie from 1926. From a stylistic point of view, too, this olive tree is exactly in a middle position between Impressionism and a drafting of color by dense backgrounds of matter, as in the revolution of the Fauves with whom he would soon share the same Mediterranean locations.

That is, of that “unparalleled garden,” as Guy de Maupassant called it, which consolidated over the years as the ideal place where Matisse could cultivate his vocation for a painting of light, color and fatally of joy.

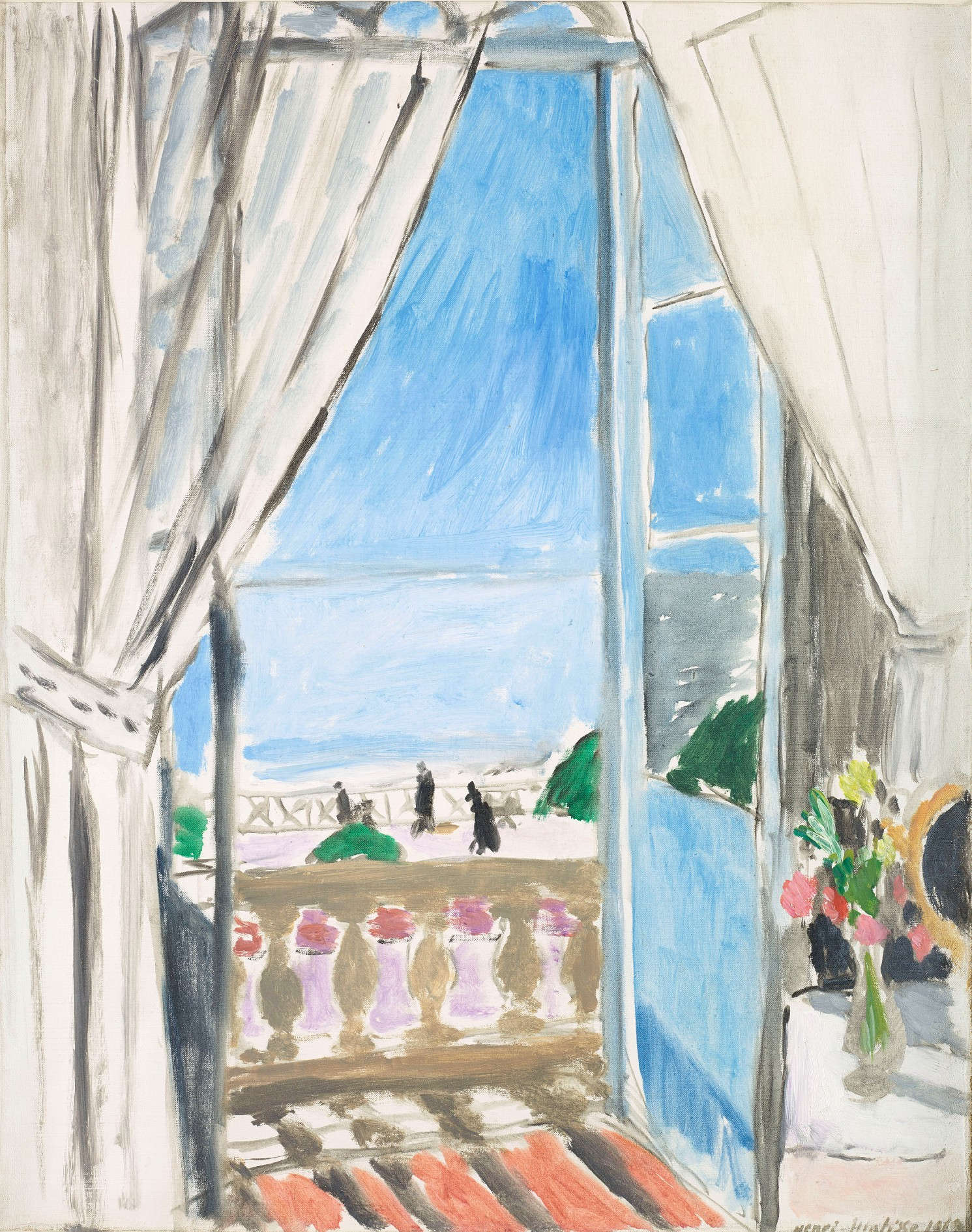

Matisse died in Nice, France, in 1954, in the same city he had immortalized well before as we are told by The Open Window of 1919-another important loan from the Centre Pompidou-which already recounts a seascape, laden with light and with that visual layout that passes for a vase of flowers in the foreground and a balustrade, perspective tools that would become one of the recurring elements of his painting.

Expanding the MUVE’s exhibition spaces beyond the Liberty Bridge means giving the opportunity to show-and sometimes reread-some rare works from the permanent collection that for obvious reasons of space are relegated to storage. This is the case with Cuno Amiet’s Siepe in the Garden (1943) or Filippo De Pisis’ splendid Grande paesaggio, unexpected in format, as much as it is anomalous but also in pictorial invention. The same two large drawings by Matisse(Fruit Fern and Female Figure and The Opaline Vase, both from 1947) that arrived at Ca’ Pesaro following the 1951 Biennale and from which the construction of this exhibition moves, are not routinely exhibited in the Venetian museum’s itinerary, “like many other important canvases that are today unfortunately difficult to include in a museum itinerary as articulated as that of Ca’ Pesaro,” - Barisoni goes on to explain “and which instead in an exhibition dedicated to French modernity establish a much more effective dialogue.”

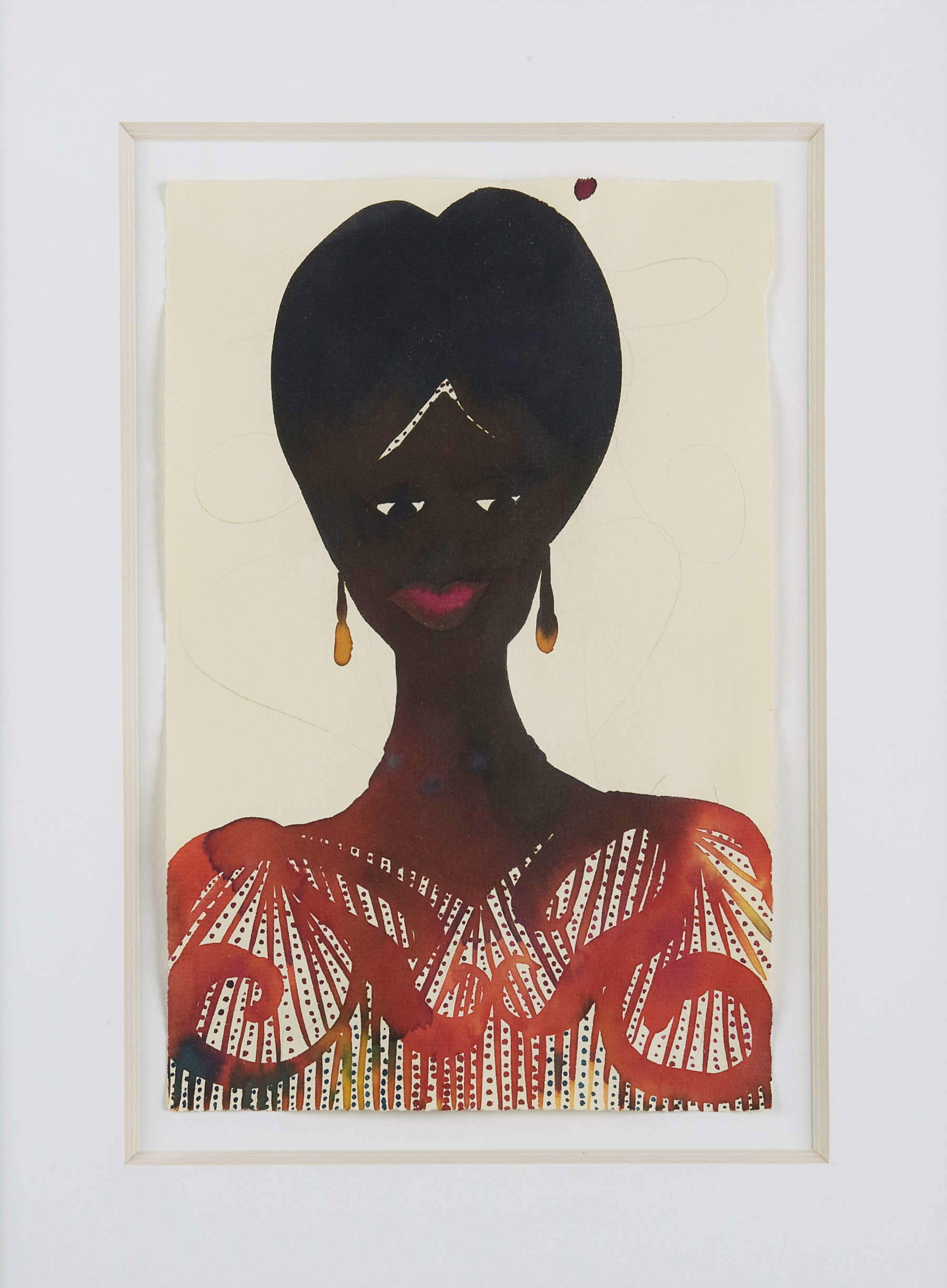

Matisse’s love for women, the prince subject of those interiors of light and color are told in a wall that holds together some masterpieces, such as The Odalisque (1925) from the Museo del Novecento in Milan and The Yellow Odalisque (1937) from the Philadelphia Museum of Art, in a fruitful dialogue with some fellow travelers such as Pierre Bonnard’s Nude in the Mirror (1931) or Raoul Dufy’s Study with Fruit Bowl (1942). Matisse marks a trail evidently also followed later by sculptors such as Emilio Greco - The Dancer (1961) - or painters such as Corrado Balest, who learned from the French master how to let the light of the Mediterranean enter the rooms, and even more recently by Chris Ofili, an artist of immense graphic elegance.

All that remains, then, is to immerse oneself in the light and color of the Mediterranean accompanied by the notes of George Garshwin’s Rhapsody in Blue to underscore how Matisse is always and everywhere the painter of joy.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.