Life or Theater? The tragic and touching autobiography of Charlotte Salomon, who died at age 26 in Auschwitz

An exhibition that already appears at first glance to be different from the others, the one dedicated to Charlotte Salomon (Berlin, 1917 - Auschwitz, 1943) that will be hosted until June 25, 2017 at the Palazzo Reale in Milan. Different because it is an exhibition that brings into play not only admiration for the works of art on display, but above all the strong emotional charge that comes from knowing a real life story: that of an artist who made her art a kind of contrivance to succeed in living her existence. Different because of how it is presented from an organizational and exhibition point of view: after an introductory video in which the visitor is anticipated, in broad outline, the story that he will read and become passionate about in the exhibition, there are various sections that do not bear titles of themes or periods, but rather designations that refer to the writing of a narrative text or a play, such as prologue, part one, part two, epilogue. Different because this is not an exhibition dedicated to an artist well known to the general public, whose name alone attracts visitors from all over, but an exhibition dedicated to an artist unknown to most, even though her story deserves to be told and remembered by all and to all.

Just to give you an idea: at the time of our visit, a long line of people crowded the square in front of the Royal Palace to visit the various exhibitions, two in particular, that the Palace was hosting at the same time, while very few people were about to visit the exhibition dedicated to Charlotte Salomon. However, we noticed a great attention and eagerness for knowledge on the part of the visitors present and participating in lingering to read each individual panel and each individual caption accompanying each work, or rather each drawing. We specify drawing because the exhibition consists entirely of tempera drawings made by Charlotte herself and telling her story. A story that allows itself to be told in a succession of different emotions that make the visitor emotionally fragile. An alternation of sadness, passing joys, fears and disturbances that invades the works and makes us identify with the events narrated by Salomon herself through her drawings, just as we would during the reading of a novel.

|

| The exhibition of Charlotte Salomon’s drawings in Milan, Palazzo Reale |

|

| The particular arrangements of the exhibition |

|

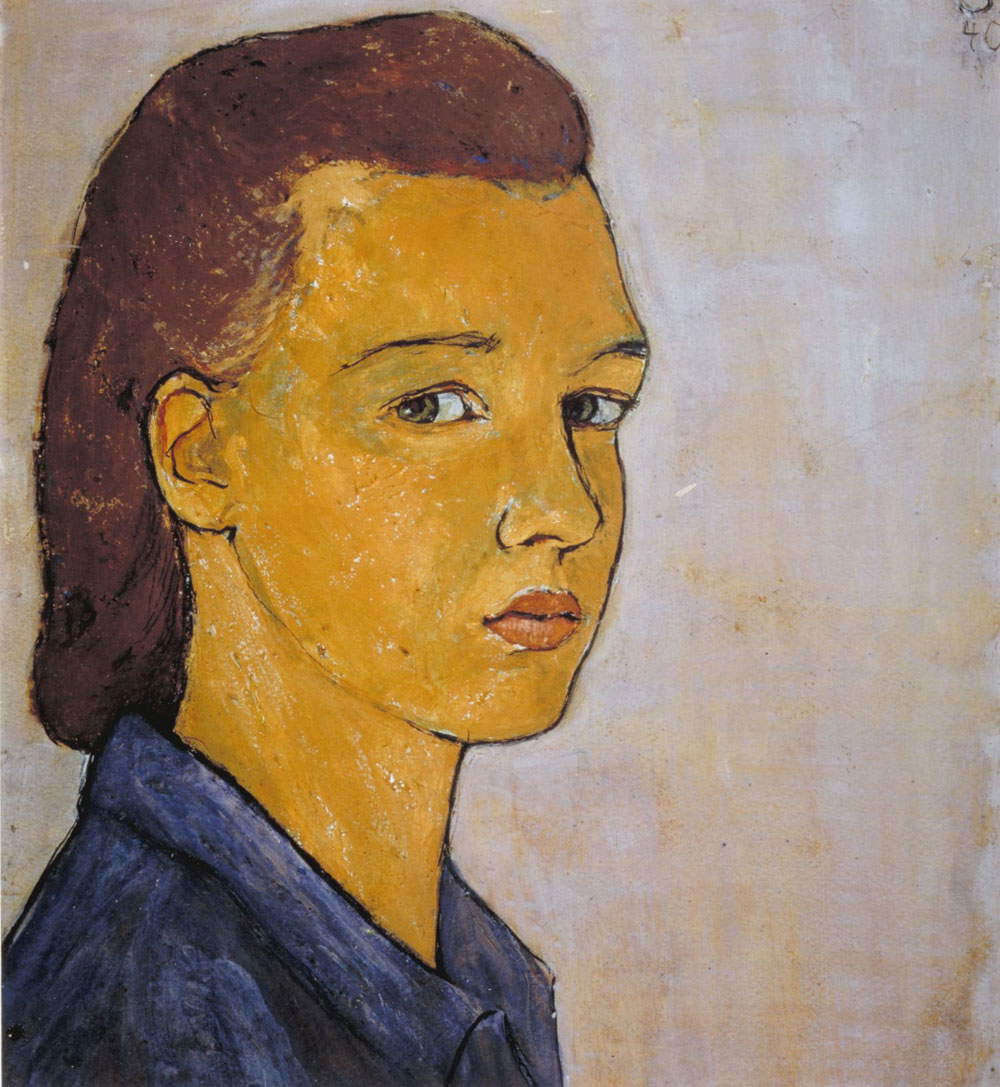

| Charlotte Salomon, Self-Portrait (1940; gouache on cardboard, 53.9 x 49.2 cm; Amsterdam, Joods Historisch Museum) |

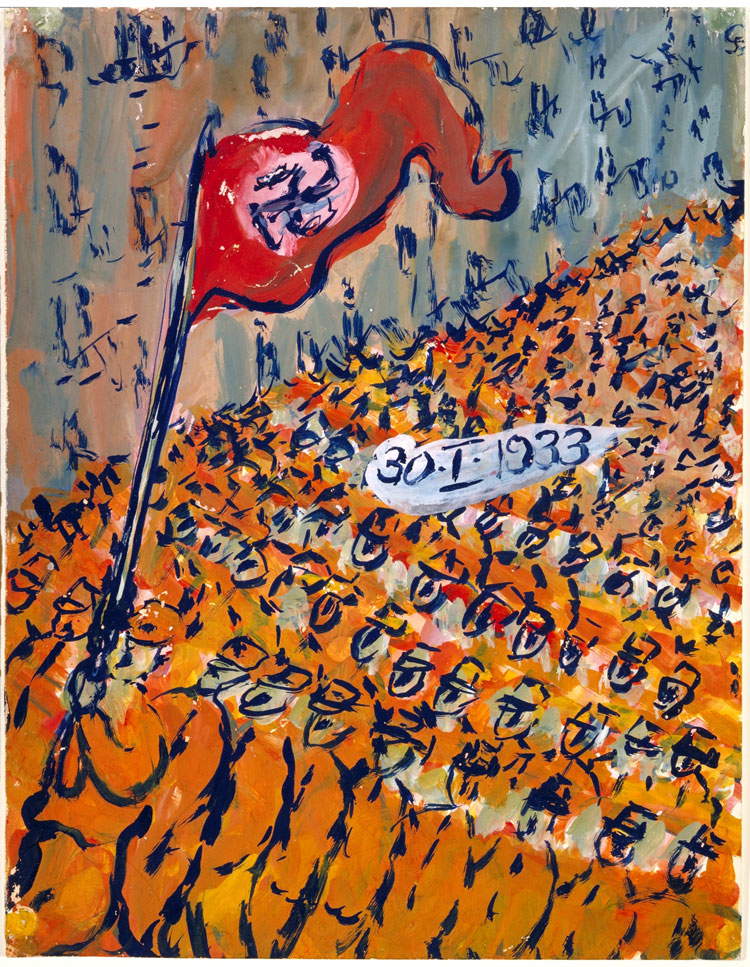

Her life was marked by a series of suicides in her family: her aunt Charlotte, from whom the artist inherited her name, threw herself into a lake; her mother took her own life by throwing herself out of a window when Charlotte was still a child; her grandmother committed suicide after an existence full of grief and suffering; it was only as a result of her grandmother’s death that the deep dark evil that had oppressed the women in her family for years was revealed to young Charlotte by her grandfather. However, these were not the only tragic events in the artist’s existence: the advent of Nazism brought further tragedy within his family since it was of Jewish origin, therefore subject to persecution and deportation to concentration camps, as in fact happened to Charlotte’s father, a university doctor, who was imprisoned and deported, but then fortunately freed thanks to the help and intercession of his second wife, Paulinka Lindberg, a famous opera singer, with whom the artist had a very good relationship.

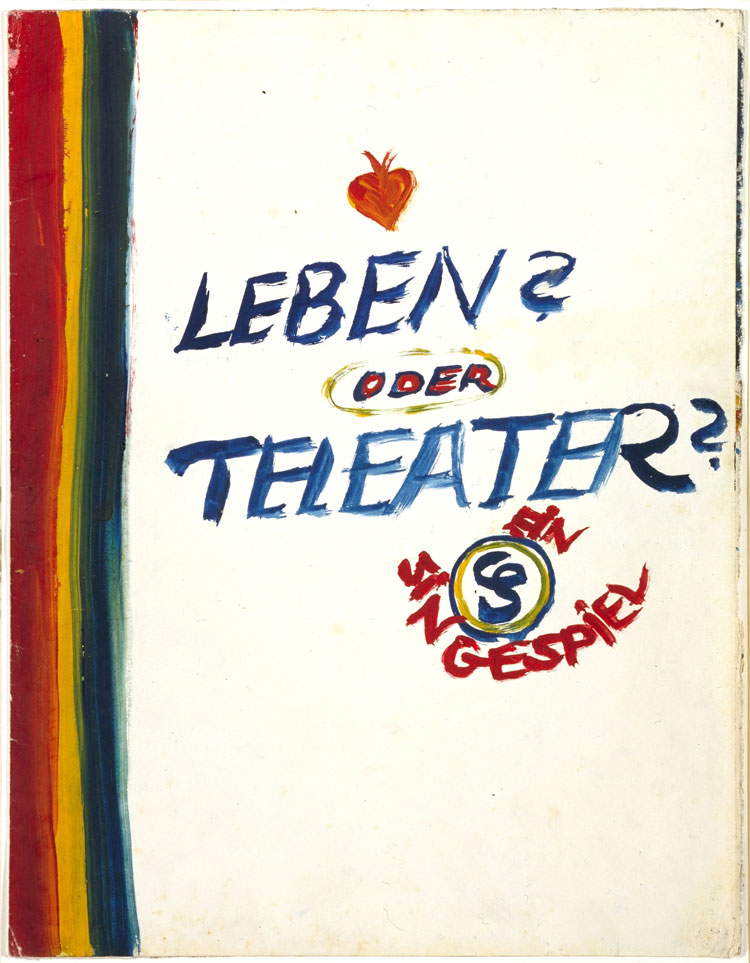

All these impatiences, fears, revelations, and misfortunes combined with the historical period in which the artist lived prompted her to create a long pictorial, theatrical, and musical narrative to which she gave the title Leben? Oder Theater? (Life? Or Theater?), which foreshadows the autobiographical matrix of the narrative. A Singespiel, that is, a poem consisting of theatrical dialogues, literary intersections and musical directions and depicted by tempera drawings by Salomon herself. Art, her greatest passion, helped her to live, to manage not to go mad, to keep going despite constant adversity. A kind of soothing for her existence.

|

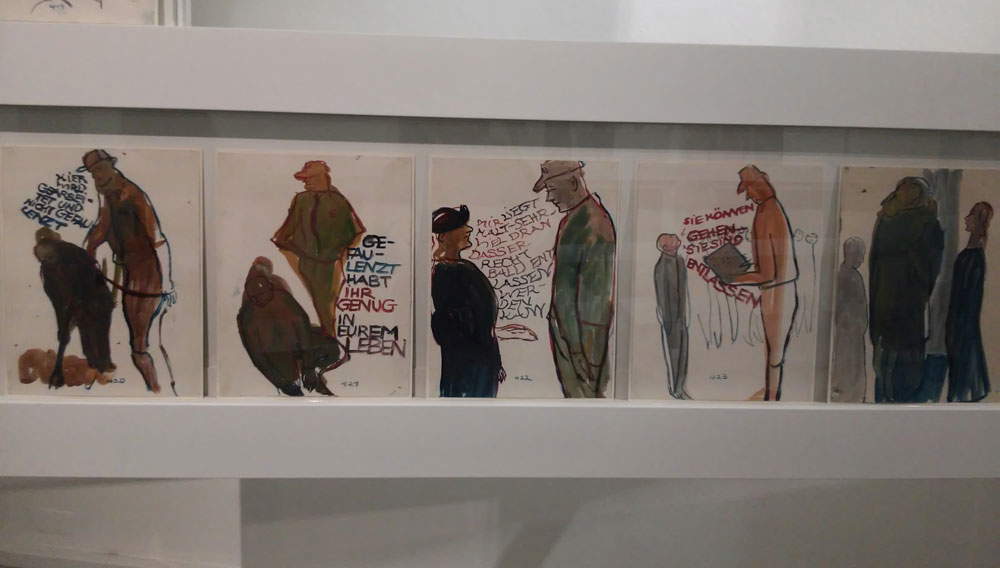

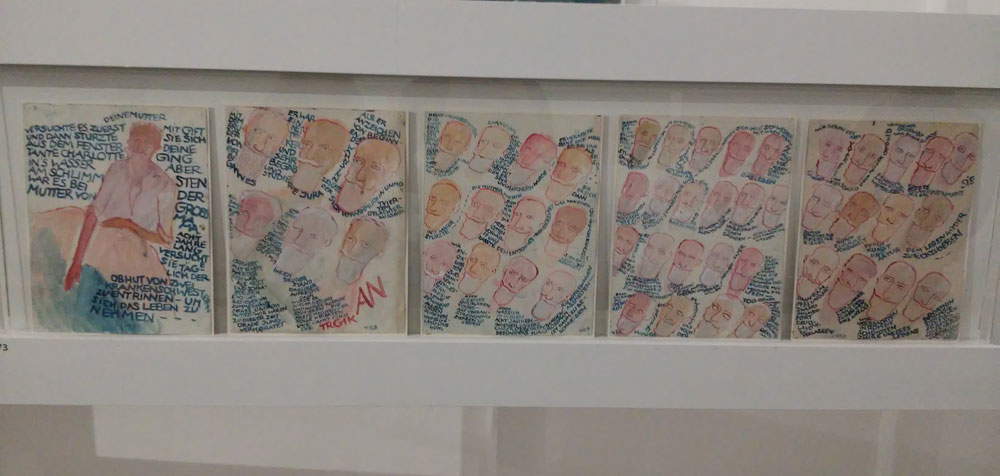

| Charlotte Salomon, Leben? Oder Theater? (1940-1942; gouache on paper, 32.5x25 cm; Amsterdam, Joods Historisch Museum) |

|

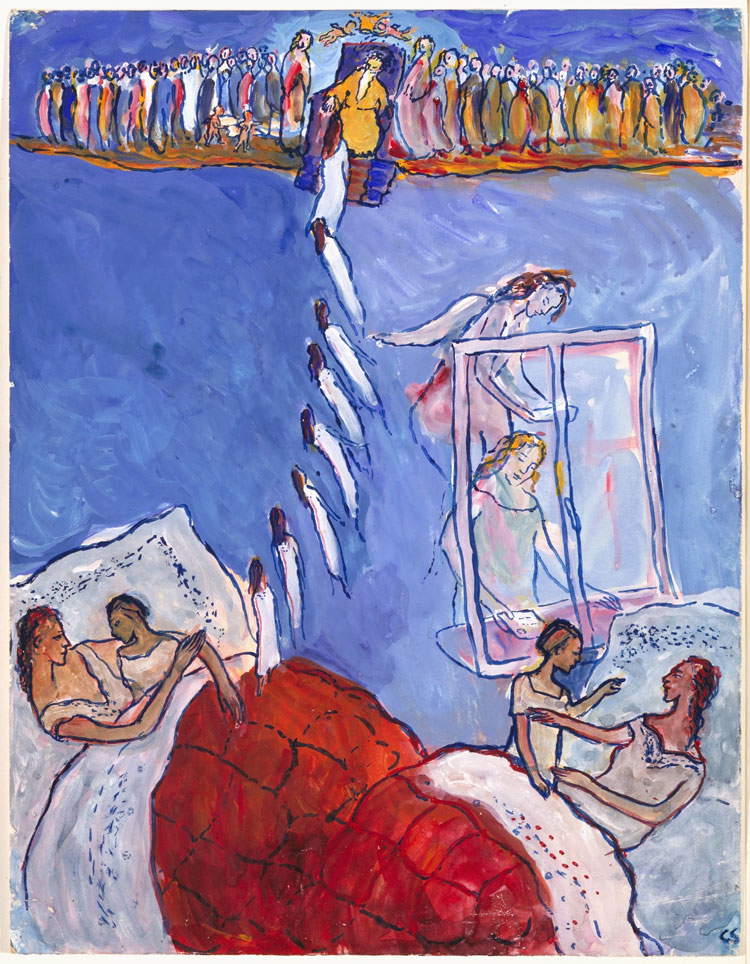

| Charlotte Salomon, Franziska often took her daughter with her in bed, and talked to her. “Everything is much more beautiful in heaven than on this earth. And when your mommy has become a little angel, she will come down and take to her little hare, bring her a letter to tell her how it is in heaven.” Charlotte found this to be very beautiful.... (1940-1942; gouache on paper, 32.5x25 cm; Amsterdam, Joods Historisch Museum) |

|

| Charlotte Salomon, On the hooked cross already hope fully appears...many Jews occupied state posts or other higher offices and after the National Socialists seized power they were all dismissed without notice... (1940-1942; gouache on paper, 32.5x25 cm; Amsterdam, Joods Historisch Museum) |

|

| Drawings recounting Charlotte’s father’s liberation from the concentration camp |

|

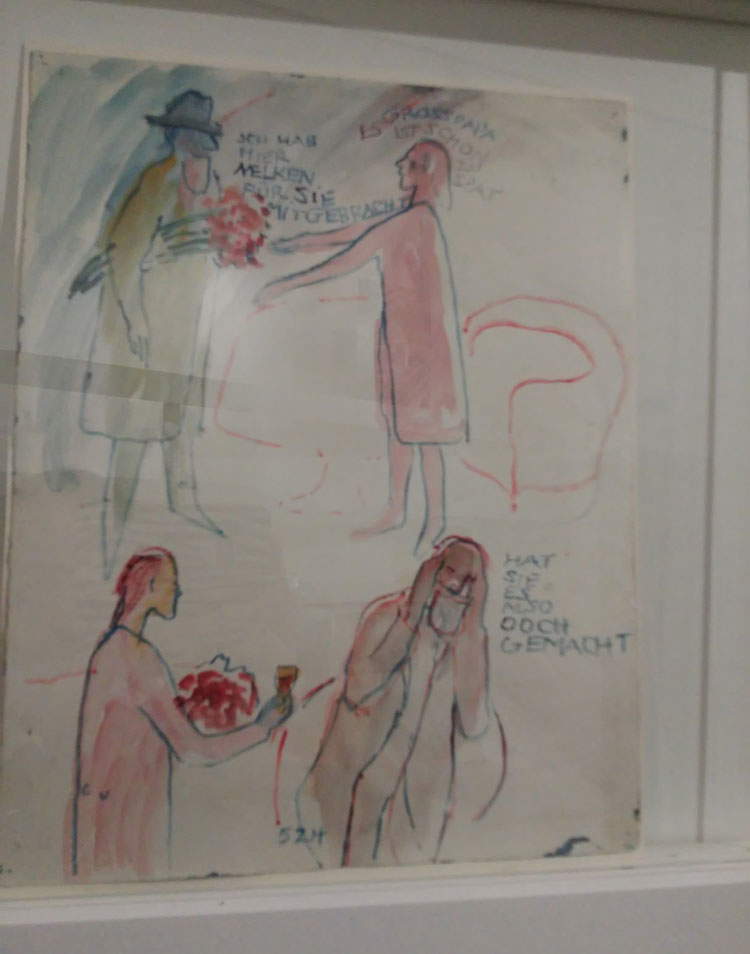

| Charlotte Salomon, Grandfather: “I got carnations for Grandma.” Charlotte: “Grandfather, it’s too late.” Grandfather : “So she finally did it” (1940-1942; gouache on paper, 32.5x25 cm; Amsterdam, Joods Historisch Museum) |

|

| Grandfather’s terrible revelations |

|

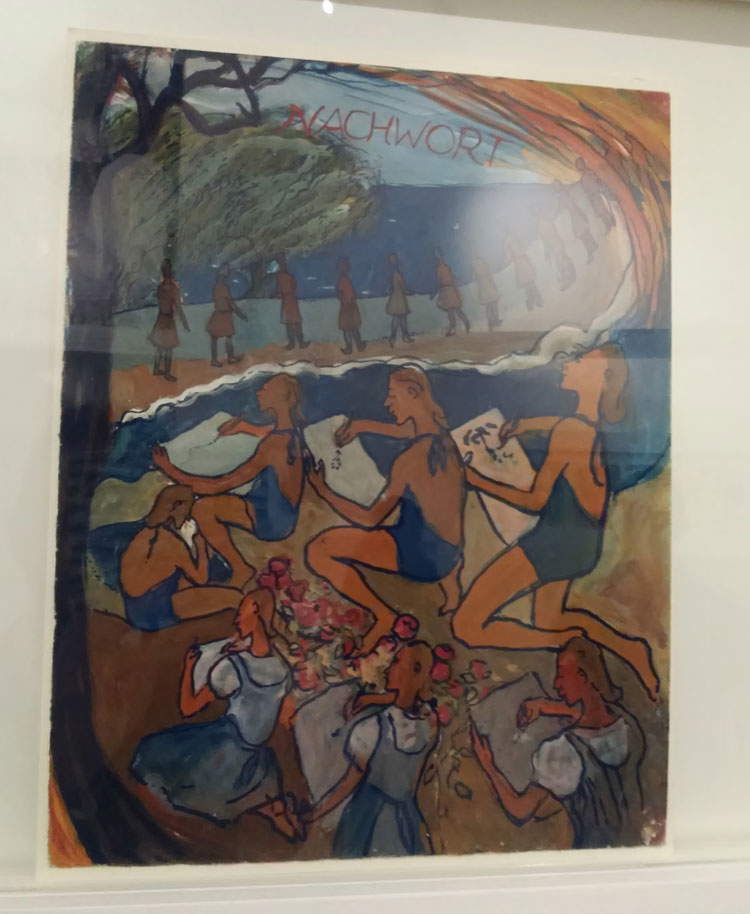

| Charlotte Salomon, On a cliff there high up grow pepper trees.... Softly the wind moves its silvery leaves. Down below dissolve the foams - in the endless expanse of the sea. Foams, dreams - dreams of mine on a blue land, what do you always manage to build again and bright from so much pain and sorrow. Who gave you the right? Dream, speak to me - and whose servant are you? Why do you save me? On a cliff up there grow pepper trees. Softly the wind moves its silvery leaves. (1940-1942; gouache on paper, 32.5x25 cm; Amsterdam, Joods Historisch Museum) |

The exhibition presents for the first time in Italy a selection of about 270 tempera paintings belonging to Life? Or Theater?: the artist mainly uses primary colors, preferring dark tones for the depiction of dramatic events, as in the cases of the death of her aunt and mother , or colors that evoke death, such as red, for the depiction of her grandmother’s death. The death of her mother was conceived by little Charlotte as the becoming reality of a phrase that her mother used to repeat to her In heaven everything is much more beautiful than on this earth. And when your mommy has become a little angel, she will come down and bring her little hare, she will bring her a letter to tell her how it is in heaven. But that letter never came.

The autobiographical tale begins with her aunt’s suicide and ends with 1940, the year Charlotte decided to bring her great poem to life: she is shown pictured in front of the sea in Villefranche-sur-Mer, a town near Nice, where she had moved from Berlin with her maternal grandparents to escape Nazi persecution, intent on drawing. Three years later, she was arrested by the Gestapo along with her husband and deported to Auschwitz where, four months pregnant, she was killed.

Life? Or Theater?, finished a few months before the artist’s death, was entrusted before her arrest to the doctor in Villefranche-sur-Mer, and after the war was given to Charlotte’s father, who survived extermination by fleeing to Holland. The artist’s family decided to entrust the masterpiece to the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam until 1971, when it passed to the city’s new Joods Historisch Museum (or, in English, Jewish Historical Museum), where it is still kept today.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.