Water is, for a painter, one of the most difficult elements to reproduce with the brush. Impalpable, irrepressible, unstable, colorless, transparent. It undulates, it flows, it moves, it ripples, it adapts, it glows, it blurs. Matter and subject at the same time, a constant source of inspiration, a liquid laden with symbolic references, a force to be mastered and harnessed, water has always fascinated artists, but the representation of such an elusive element has always posed a problem: if the first to become aware of it was Cennino Cennini, who in his Libro dell’arte first provided technical indications on how to paint it (“when you wanted to make a water, a river, or what water you wanted, either with fish or without fish, in wall or true in table; in wall, remove that same verdaccio that aombri i visi in su la calcina; fare i pesci, aombrando con questo verdaccio pur sempre l’ombre in su’ dossi [...]. And if you do not wish to do it in oil, remove verdeterra or green-blue, and cuopri for everything equally; but not so much, that fishes and waves of water do not always shine through; and, if need be, white the said waves a little on the wall with white, and on the table with tempered white lead.”), Leonardo da Vinci (Vinci, 1452 - Amboise, 1519) nevertheless deserves the primacy in having made water the object of systematic studies. Irving Lavin and, before that, Kenneth Clark, have written that for Leonardo water constituted an obsession, and it is not difficult to believe them: it is one of the most present themes in his treatises, it is the main subject of the so-called Codex Leicester, and it should have become the protagonist of a First Book of Waters that was never completed. “Water,” Martin Kemp has recently written, “is present in more than half of Leonardo’s paintings, both explicitly, depicted as a visible subject, and implicitly, in relation to the powerful action exerted in the transformation of the Earth over very long periods of time.” It is beyond interesting to note how, in a drawing preserved in the collections of the royal family of England, Leonardo likened the surface of water to a fleece, and its motion to that of hair: “note the motion of the fleece of water, which makes use of the hair, which has two motions, of which the one attends to the weight of the fleece, the other to the lynching of the vaults; thus the water has its revertiginous vaults, of which one part attends to the impetus of the main course, the other attends to the incidental and refressed motion.”

Whirlpools, currents, eddies, ripples and waves do not appear in Leonardo’s work only in paintings or drawings depicting water. They often take the form of the flowing hair of his characters: a particularly emblematic case is that of the Scapigliata (or Scapiliata, if one wants to use the adjective that appears in the Gonzaga inventory of 1627, moreover on display in the exhibition, in which Leonardo’s “head of a scapiliata woman” is mentioned, and which many have wanted to identify with the famous work now in the National Gallery in Parma). In this archaic panel sketched with white lead and iron and cinnabar pigments, the protagonist’s hair takes on the appearance of small waterfalls that fall slightly moved by the wind, of rivulets that swirl in every direction, of waves that curl and twist. Kenneth Clark, while never mentioning the Scapiliata in his famous biography of Leonardo, wrote that the artist felt that movement, to be eternalized through art, should be a visible expression of grace. And although there are no formal, precise definitions of “grace” in the Renaissance, the latter is to be found “in fluid gestures, fluttering draperies, curly or wavy hair,” to use Clark’s words. Water, the “vettural of nature,” as Vincian called it, is a perfect metaphor for the continuity of movement that gives rise to grace: aesthetics and philosophy (the movement of hair that brings grace, that of water that brings life) merge in a continuous connection that aroused Leonardo’s attentions with great frequency.

These are some of the topics that animate the exhibition The Fortune of Leonardo da Vinci’s Scapiliata, curated by Pietro C. Marani and Simone Verde and set up in the halls of the National Gallery of Parma until August 12, 2019, to shine new light on the tablet (which most now want to be fully Leonardo-esque) on the 500th anniversary of the artist’s death. A small but dense review to take stock of three main issues: the authorship of the Scapiliata, its place within the context in which it would have been produced, and its later fortunes. There is also a focus on collecting in Parma: as is well known, the tablet attributed to Leonardo da Vinci made its entry into art history on a precise date, 1826, when the heirs of the painter Gaetano Callani (Parma, 1736 - 1809) offered it to theAcademy of Fine Arts in Parma, which, however, did not seize the opportunity since the work entered, in 1839, the collections of the Galleria Palatina (with attribution to Leonardo), without it having left the Parma collection since then.

|

| A room from the exhibition The Fortune of Leonardo da Vinci’sScapiliata |

|

| A room from the exhibition The Fortune of the Scapiliata by Leonardo da Vinci |

|

| A room from the exhibition The Fortune of Leonardoda Vinci’s Scapiliata |

The main novelty of the National Gallery’s exhibition concerns the results of the analysis to which the Scapiliata was subjected just in time for the event. And the starting point of the investigation conducted by Diego Cauzzi, Gisella Pollastro and Claudio Seccaroni is the beginning of an article, published in 1939, by Armando Ottaviano Quintavalle, who began by writing that the Scapiliata “is a sketch on shadow ground on board of m. 0.247 x 0.21 impiastricciato di vecchia ambra inverdita.” It is on thatinverted amber (whose presence was highlighted by Quintavalle not through technical analysis, but exclusively through the depth and experience of his eye) that the attentions of many scholars have focused: since Leonardo, in his Treatise on Painting, referred to a varnish of “oil of walnut and amber,” one wanted to see in this varnish a proof of his hand. In reality, works in which Leonardo uses varnish with amber are rare, and non-invasive analyses have definitively clarified that, in fact, the one affixed on the Scapiliata is a modern varnish (and it is worth noting that, as Seccaroni and colleagues rightly observe, no one has ever wondered “why Leonardo would employ a varnish on a barely sketched tablet”). Fluorescence x analysis then provided several interesting data. The most important result, the three scholars point out, is the information they were able to obtain about theimprimitura of the panel, "made up of a mixture of lead-based pigments (white lead in primis, but the use of lead and tin cannot be excluded), copper-based pigments and lead and tin yellow: this would be a preparation also described by Leonardo, and in particular in a note that appears on paper 1r of Manuscript A preserved at the Bibliothèque de l’Institut de France (Leonardo speaks of an “imprimitura of thirty parts of verdigris and one of verdigris and two of yellow”). The fact that the artist repeated verdigris twice is, according to scholars, a typo “amendable by re-establishing as the first ingredient the one used in greater proportions, white lead.” And again, the support was also examined: charitated with autopsy investigation that it is walnut wood (material used by Leonardo for all his Milanese paintings), emphasis was placed on the vicissitudes it has undergone over time.

In particular, the hypothesis according to which the Scapiliata could be the fragment of a large composition has been discarded: “the characteristics of the support,” say the scholars, “show that it has not been reduced except in a small part, as attested by the chamfer on all four sides, which indicates that the thin board should originally have been embedded in a frame with the function, also, to counteract the natural movement of the wood as a result of environmental hygrometric stresses.” A structure also documented in other coeval works. It is certain, however, that the work was resected and altered later, with obvious cuts and retouches, which is why, in all likelihood, the image we see today is not the same one Leonardo also saw. Pinin Brambilla Barcilon, a restorer with a deep knowledge of Leonardo’s work (she is best remembered for her restoration of theLast Supper), has written well on such retouching, pointing out that the face appears “repassed in some portions, evident at the profile and especially at the gaze, altered by a retouching in the cut of the left eye: the resulting shading generates a disturbance in the compositional balance and seems to modify the somatic data.” Brambilla Barcilon also believes that the wavy locks do not belong to Leonardo’s hand: in his opinion, the freedom of stroke that, on the contrary, seems to characterize the broad brushstrokes on the sides of the head does not fit Vinci’s genius.

Then there are the new hypotheses about the chronology of the Scapiliata within Leonardo’s production: on one of the last occasions when the Scapiliata had been exhibited outside Parma (i.e., the major exhibition on Leonardo at the Palazzo Reale, Milan, in 2015), Pietro C. Marani carded it with chronology 1504-1508, thus placing the panel next to the Leda, to whose realization the artist from Vinci waited in that turn of the year, and to the Madonnas that Leonardo was executing around 1508 for Louis XII of France (the “two our Women of various sizes” of uncertain identification). On this occasion, Marani instead proposes a different date, between about 1492 and 1501: to the last decade of the 15th century, meanwhile, would refer the conceptual proximity to a passage in the Treatise on Painting (datable to 1490-1492), in which indications are given on how to depict hair ("fa tu adonque alle teste li capegli scherzare insieme col finto vento intorno alli giovanili volti, e con diverse revolture graziosamente ornargli. And do not do as those who impiastrano them with glues, and make the faces look as if they were glazed; human follies in augmentation, of which it is not enough for sailors to bring from the east par

|

| Leonardo da Vinci, Head of a woman known as “La Scapiliata” (c. 1492 - 1501; white lead with iron and cinnabar pigments, on white lead preparation containing copper, lead yellow and tin pigments on walnut panel, 24.7 x 21 cm; Parma, Complesso Monumentale della Pilotta, Galleria Nazionale) |

|

| Leonardo da Vinci, The Scapiliata |

|

| Leonardo follower, Leda and the Swan (first decade of the 16th century; oil on panel, 130 x 77.5 cm; Florence, Uffizi Gallery) |

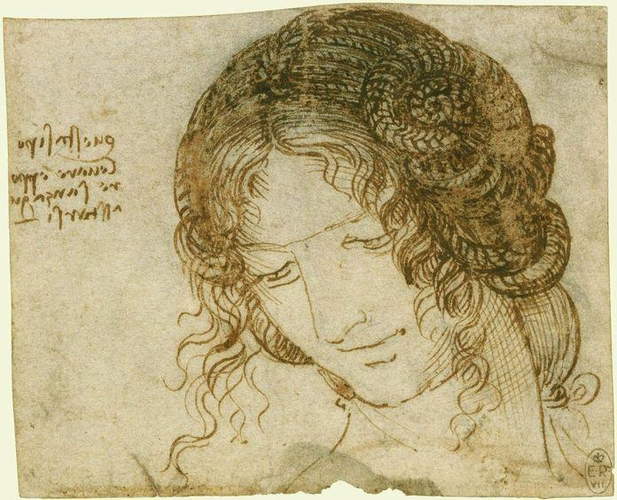

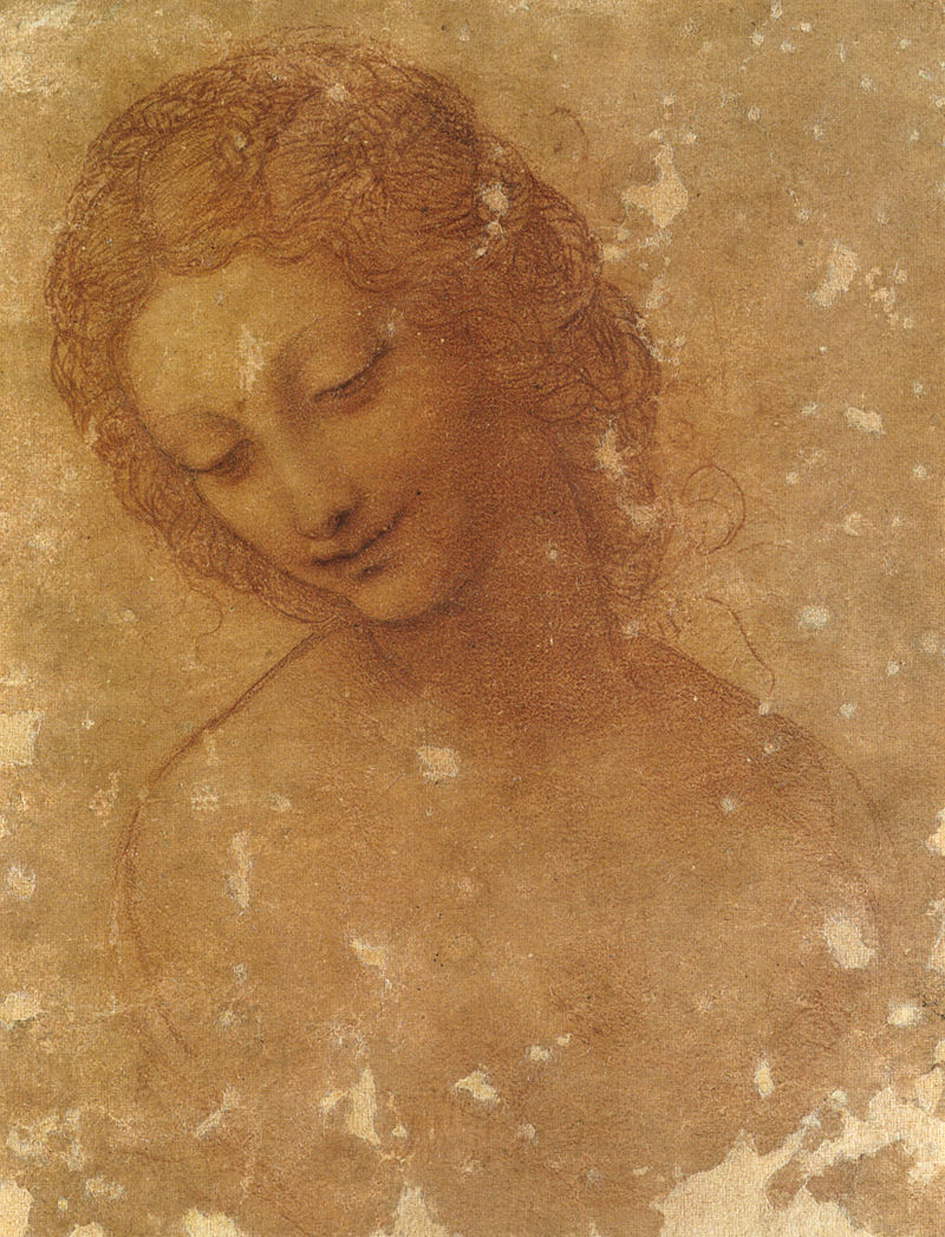

On this latter basis are grafted the possible comparisons with other similar works in Leonardo’s production, some of which are offered directly to the public in the exhibition. The drawings that come from the collections of the British royal family (two studies for the hairstyle of a woman, related to the Leda on which Leonardo was working in the early 16th cent: in Parma is the version drafted by a follower of the master and now in the Uffizi) demonstrate the effort that the artist from Vinci was putting, at the beginning of the sixteenth century, into outlining a female figure with windswept hair, with careful study of the hairstyles (and with the locks waving in a manner not unlike the way we see them in the Scapiliata): the fact that the artist paid more attention to the hair than to the face (which appears rather typecast, in contrast to the hairstyle) shows unequivocally that Leonardo’s attentions were focused on the former at that juncture. Yet one cannot help but notice that the inclination of the faces, the attitude and the gaze have several points of contact with the profile of the Scapiliata: to complete this crossroads of physiognomic similarities also comes the Study for the Head of Leda, a much-discussed work (some have even denied its autography) and in a less than optimal state of preservation, but one that fits into the fortunate vein of female faces on which Leonardo invented and experimented to find a hairstyle in line with his thoughts. Hair had, after all, long been an important field of experimentation for many artists (we need only recall Sandro Botticelli’s enchanting women or Pollaiolo’s accomplished damsels), but the novelty of Leonardo’s approach lies in his insistence on the movement of the hair to give naturalness and breathe life into the characters.

And it is precisely on the theme of movement (first understood in a broad sense, and then restricted to the movement of hair) that the exhibition avowedly intends to place Leonardo’s contribution historically: first, with the opening section, by framing the events that would lead to the Scapiliata, and then, through the second of the exhibition’s four rooms, by investigating the contributions of the artists who took up the challenge thrown down by the Vincentian. The first part turns out to be rather weak: except for a couple of ancient coins and a singular Couple in Flight from the House of the Dioscuri in Pompeii and preserved at the National Archaeological Museum in Naples, the only loan in this first part, the itinerary seems, if anything, aimed at tracing the lines of the iconography of female faces through a number of works from the collection of the National Gallery of Parma. And if the relations of the latter with the Scapiliata appear somewhat labile, their only function would seem to be to prepare a brief and concise summary of the stages that led Renaissance artists to develop a more natural painting also through reference to ancient art. Better structured is the second section, which examines the echoes of Leonardo’s lesson: Marani points out that Leonardo’s presence in Milan induced some painters, such as the Master of the Pala Sforzesca, Giovanni Agostino da L odi (Lodi, c. 1470 - c. 1519) and Bernardino Luini (Dumenza, c. 1481 - Milan, 1532), to reflect on "the typology of a female face ’framed’ by floating hair: such is the face of the woman with loose hair and a pearl necklace depicted by the Master of the Pala Sforzesca in a drawing kept in the Veneranda Biblioteca Ambrosiana in Milan (so similar to Leonardo’s graphic evidence that it was once thought to be an autograph), and similar features manifest in the striking Head of a Young Man with Thick Hair by Giovanni Agostino da Lodi, arriving from the Louvre, or Luini’s Salome, on loan from the Uffizi (a painting in which the protagonist’s profile, her hairstyle, and the inclination of her face closely recall Leonardo’s studies: in the catalog, Rosalba Antonelli goes so far as to explicitly relate it to the Scapiliata).

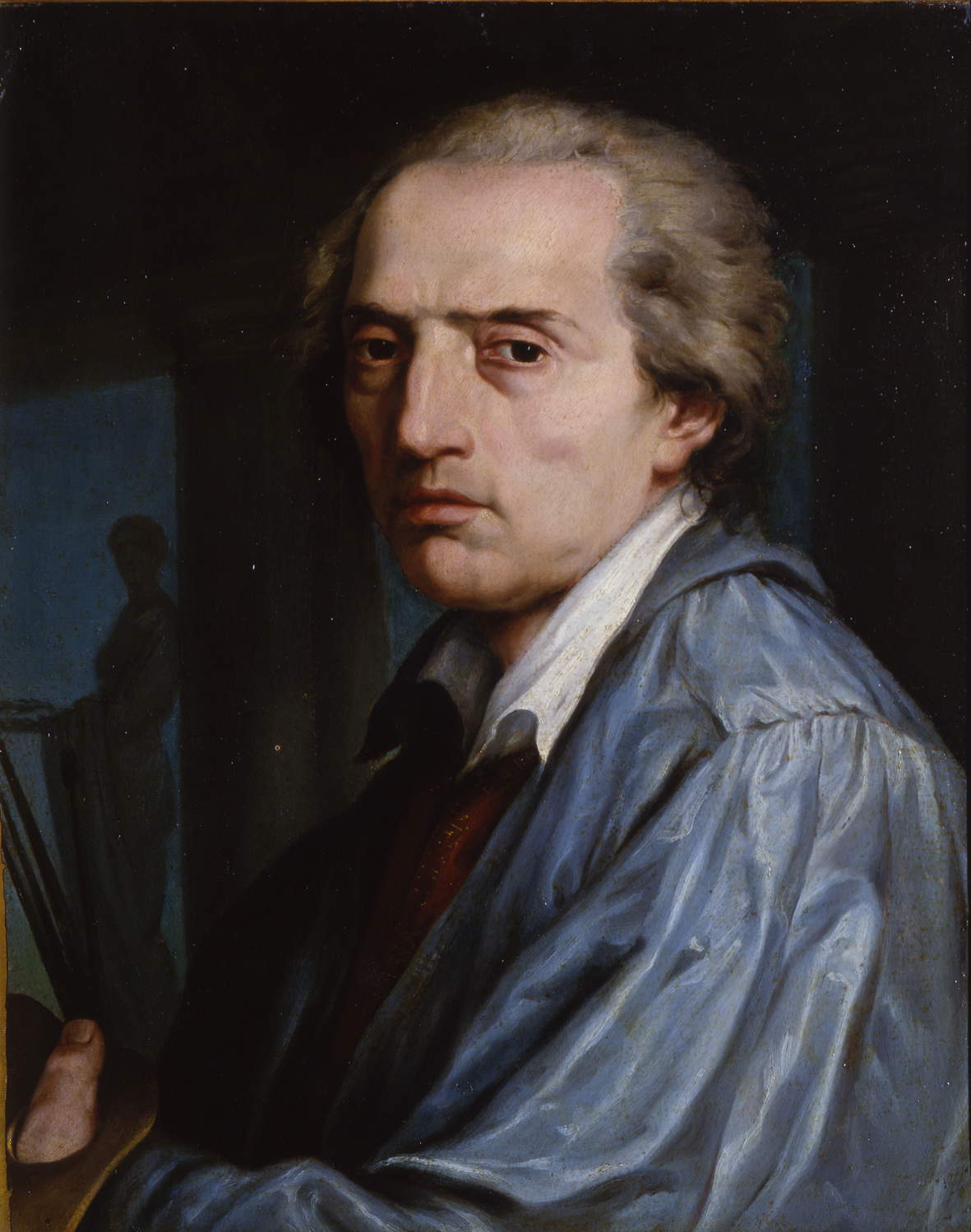

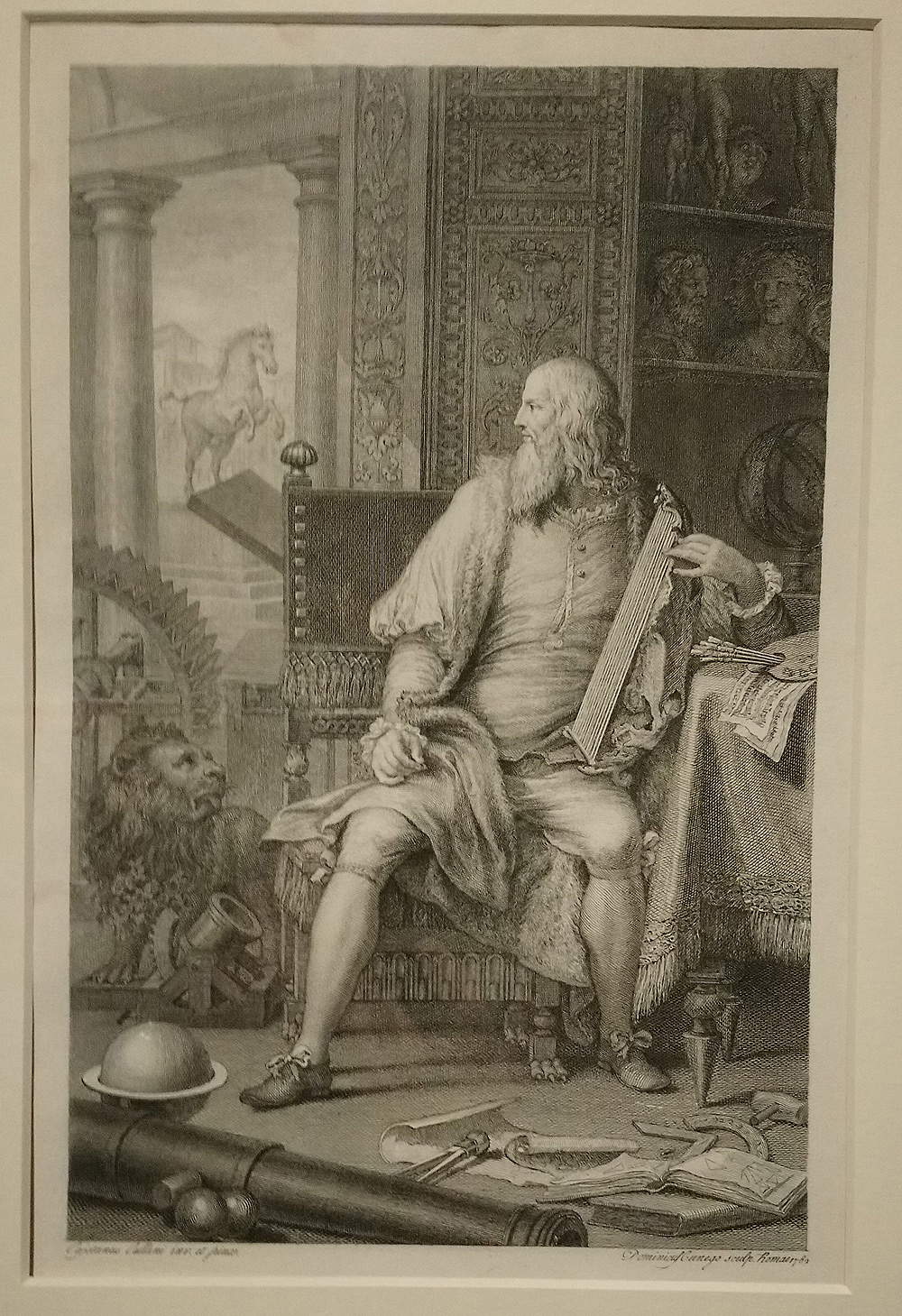

The last two rooms are devoted to collecting in ducal Parma, a theme closely related to the Scapiliata, given the circumstances under which the work arrived in the city. The importance of the figure of Gaetano Callani, “the artist of greatest fame in the Bourbon duchy at the end of the 18th century” (such is the opinion of the scholar Alberto Crispo) is thus emphasized by exhibiting a significant nucleus of his collection: Of particular note are his portrait executed by his daughter Maria Callani (Milan, 1778 - Parma, 1821), documents thanks to which it has been possible to reconstruct the events that brought the Scapiliata into the collections of the Galleria Palatina, as well as a watercolor on paper depicting Leonardo da Vinci in his studio, and the later translation of the latter into an etching print executed by Domenico Cunego (Verona?, 1724 or 1725 - Rome, 1803). The latter two works, in particular, represent clear evidence of Callani’s strong passion for Leonardo da Vinci (so much so that in the past there was even the suspicion that he, as a good copyist from antiquity, was the author of the Scapiliata): it was also thanks to Callani if interest in Leonardo and in the sixteenth century in general experienced a certain impulse. The reconstruction of the acquisition of the Scapiliata also allows us to admire some paintings that entered the ducal collections in the same period: they range from late 15th-century works such as theApostle by Bernardino Butinone (Treviglio, ante 1453 - 1510) and through the 16th century represented by a remarkable painting of local scope, the Portrait of Anna Eleonora Sanvitale executed by Girolamo Mazzola Bedoli (Viadana, c. 1500 - Parma, 1569), we come to the pair of portraits attributed to Frans Pourbus the Younger (Antwerp, 1569 - Paris, 1622), lofty examples of Flemish portraiture of the early 17th century. In short, we are going beyond the basic theme of the exhibition, but it should be emphasized that with these last two sections an interesting in-depth popularization has been created at no cost, since all the works on display are the property of the National Gallery and have simply been moved from one room to another: an operation that leads the exhibition to abandon the discourse on the Scapiliata, and, if anything, uses it as a starting point to give life to an interesting focus that demonstrates how a museum’s collection is enriched, how the purchase of a masterpiece is a practice that is part of the normal policies of expansion of a collection, and how the museum is a living organism.

|

| Leonardo da Vinci, Study for the Hairstyle of a Woman (c. 1504-1506; pen and ink on white paper, 92 x 112 mm; Windsor Castle, Royal Library) |

|

| Leonardo da Vinci (with later resumes?), Study for the Head of Leda (c. 1504-1506; natural stone on red-pink prepared paper, 200 x 157 mm; Milan, Castello Sforzesco, Civico Gabinetto dei Disegni) |

|

| Giovanni Agostino da Lodi, Head of Young Man with Thick Hair (c. 1505; red pencil, traces of black outlining, 82 x 99 mm; Paris, Musée du Louvre, Cabinet des dessins, Fonds des dessins et miniatures) |

|

| Bernardino Luini, |

|

| Maria Callani, Portrait of her father Gaetano Callani (1802; oil on panel, 49 x 40 cm; Parma, Complesso Monumentale della Pilotta, Galleria Nazionale) |

|

| Domenico Cunego, Leonardo da Vinci in his studio (1782; etching, 319 x 206 mm the print, 381 x 241 mm the sheet; Parma, Complesso Monumentale della Pilotta, Palatina Library, Ortalli Collection) |

|

| Bernardino Butinone, Apostle (c. 1485-1490; oil on panel, diameter 23 cm; Parma, Complesso Monumentale della Pilotta, Galleria Nazionale) |

|

| Frans Pourbus the Younger, Portrait of a Gentleman and Portrait of a Gentlewoman (first decade of the 17th century; oil on canvas, 57 x 47 cm the former, 57 x 48 cm the latter; Parma, Complesso Monumentale della Pilotta, Galleria Nazionale) |

One is accompanied toward the exit by a final in-depth look at Leonardo’s panel, all dedicated to the recent investigation campaign: photographs of scientific analyses and a rich illustrative apparatus allow visitors to delve into all the issues related to the restoration, from preparation to varnish, from support to pictorial film. And regarding the latter, it will be worth returning at this point to what emerged from the studies, not least because of the fact that an in-depth examination of the pictorial drafting could help us unravel the doubts regarding the possible destination of the work. It has been found that the work is brought to an almost final stage in the face (executed through various superimpositions of dark and transparent colors alternating with light ones that the artist laid down in broader brushstrokes), while the rest (the top of the head, the shoulders, the neck, the hair itself) has been left in a sketchy state.

What, therefore, is the purpose of a painting done in such a manner? Marani, in his essay in the catalog, wonders “whether the Parma painting is not an experimental sketch for a theme in which to represent precisely the effects of the wind, choosing as his subject either a mythological or antiquarian theme, drawn from the many examples provided by Antiquity [...] and suggested perhaps by the vision of some bas-relief depicting Nereids, Maenads or figures of dancing Nymphs.” A theme that Leonardo could later develop with his Leda, given also its remarkable proximity to the Scapiliata. In essence, an experiment, deliberately left unfinished, but Marani also puts a new hypothesis on the scales, suggesting a link between the Scapigliata and some biblical or New Testament theme: the scholar believes that certain works by Luini (one is seen above) on these subjects demonstrate a knowledge of the Scapiliata. And it is therefore plausible, according to the art historian, “that the Parma painting is nothing more than a study for a composition having one of these themes for its subject.” The new studies on the Scapiliata and the new hypotheses on its dating and destination help to make this exhibition one of the most interesting Leonardo appointments of the year (nor, however, should the well-conceived popularizing purposes be overlooked, which take the form of a very rich itinerary for the general public): and if in the end there is no particular news about that fortune evoked by the title of the exhibition (Luini’s proximity to the tablet had, after all, already been noted in the past), there is nonetheless material to give experts a chance to return to a discussion of the beautiful young woman with the uncombed hair.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.