Italy is a Desire. Photographs, Landscapes and Visions (1842-2022), on view through Sept. 3 at the Scuderie del Quirinale in Rome, is a meeting of the Alinari Foundation for Photography and with the Museum of Contemporary Photography-Mufoco. I saw it twice, this exhibition. The first one struck me, maybe I didn’t understand it, however, it had stuck with me like when you know a new love but you don’t know yet what it will become. And so I went back to see it, with a more conscious look, and I was overwhelmed. This is not to say that it is a difficult exhibition, or that it cannot be understood at first glance. Like great stories, it can be read on several levels, and enjoyed with the eyes, with the heart, and with the head; one or all, that choice is left to the visitor.

The exhibition offers a selection of more than 600 works, taken over 180 years, from 1842 to 2022, by artists, amateurs, and professional photographers. Structured according to a chronological path, it presents on the second floor of the Scuderie del Quirinale the photographs belonging to the Alinari Archives, one of Italy’s largest collections of photographic documentation that preserves works dating back to the dawn of photography. The second floor, on the other hand, displays works from the collections of the Cinisello Balsamo Museum of Contemporary Photography, a photographic heritage of two million images from after World War II to the present day. The distracted visitor, or simply fascinated, will notice no solution of continuity, thanks in part to what the curators have called “sparks,” moments of encounter between the two collections by themes, places or simple visual assonances that reshuffle the chronological order and suggest food for thought.

But first and foremost it is the gaze that is affected. The images fill the eyes, following one another with a rhythm that resembles a musical score: large, but also small, single or in groups, in black and white, or sepia-toned by time, but also in color. They are often recognizable representations, because they have already been seen or more simply because they are part of that photographic history that one step at a time has helped build our country’s collective imagination. Alongside these are previously unseen viewpoints, captured by the valuable work done on the archives by exhibition curators Matteo Balduzzi and Rita Scaroni, with overall coordination by Claudia Baroncini and Gabriella Guerci. There is almost no need to read the captions, which I imagined were intentionally small for this very purpose: just be overwhelmed by the succession of images to have a fulfilling experience. After the first impression, a second, stronger one emerges, one that strikes at the heart: the awareness that all this overlapping of visual impulses hides one wonderful story, that of the construction of our èaese, its identity, its culture. The key, the title declares, is landscape. But what is landscape?

Set-ups of the

Set-ups of the Set-ups of the exhibition Italy is a

Set-ups of the exhibition Italy is a Set-ups of the exhibition

Set-ups of the exhibition Set-ups of the

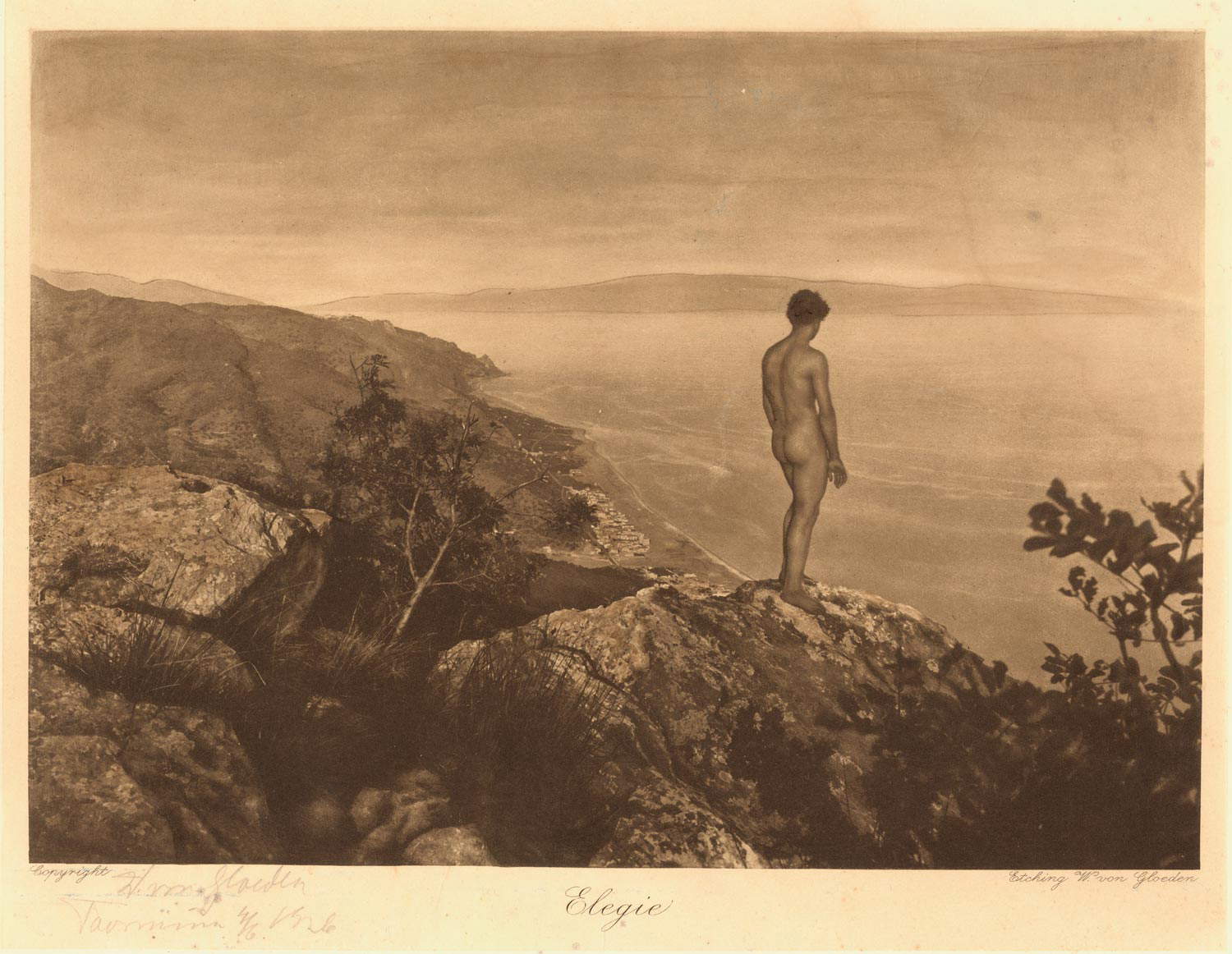

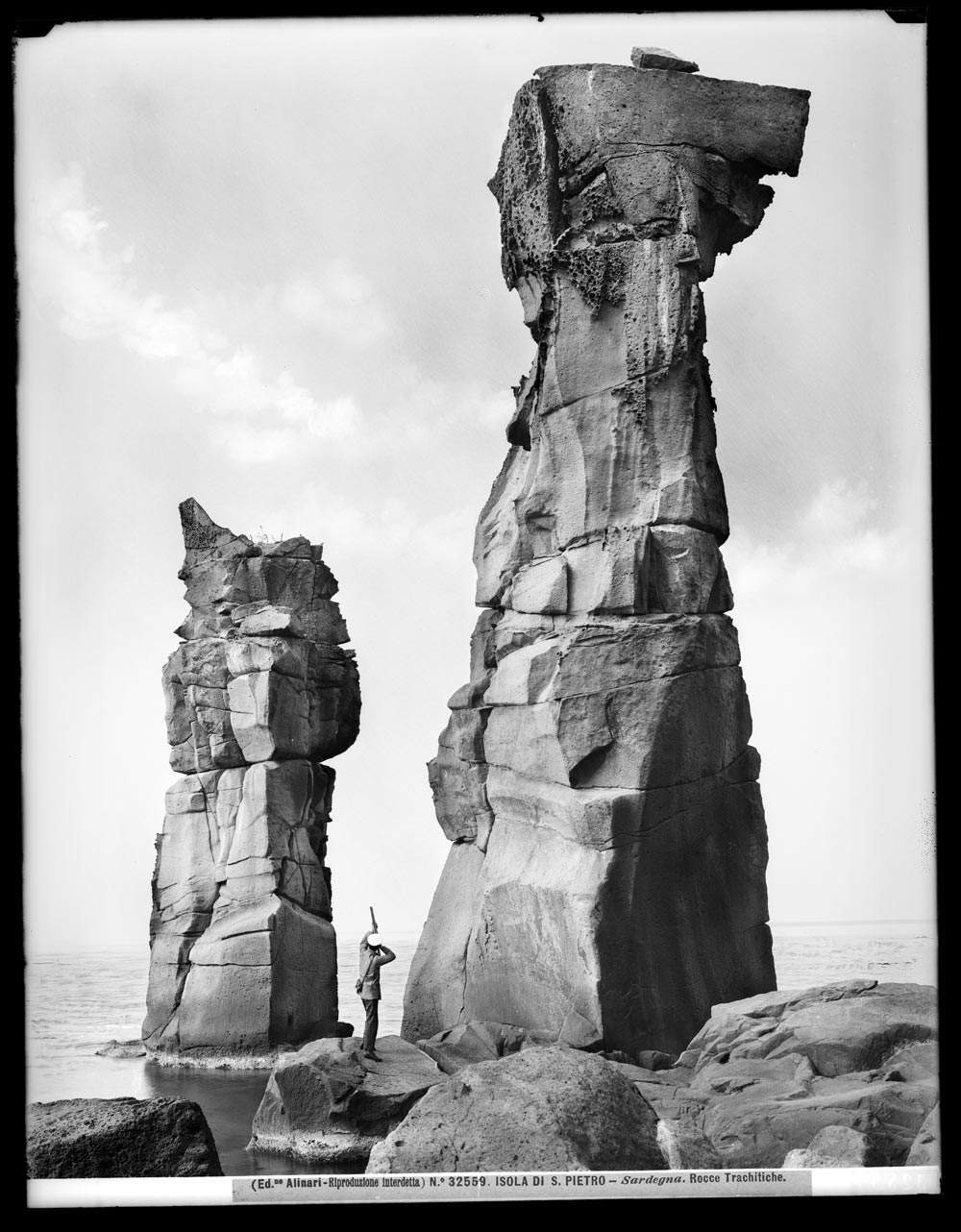

Set-ups of theIn the first part, nature, open spaces, and glimpses of the sea are the protagonists of the landscape. The gaze of the photographers of the nineteenth century and the first half of the twentieth century, whose works are preserved in the Alinari Archives, is on the great panoramas of Rome and Florence, but also the places of the myth of travel in Italy. It was thanks to those images, which were meant to tell the monto the most desired Italian destinations, that little by little the idea of Bel Paese that we exported to the world was formed. Through those same images came the knowledge and sharing of a territory that had recently been united under one state, and that always valued being deeply anchored in the province, in the different provinces that made it up, giving territory and landscape the highest place in defining cultural identity. “The real wealth,” says Davide Rondoni, president of Mufoco, “is the viewpoint. It is not what you have in your pocket, but what you hold in your gaze. Poets, strange beings who walk around with their eyes open, and translate the subtle and varied language of the landscape, know this. And photographers know it. They translate, yes, that mute language, synthesis of nature, history and culture, into human language, of words or images. Each place speaks, becomes a co-author of the poem. Or of photography. Would we have Montale without the roughness of the Ligurian coast? Pavese without the hills of the Langhe? Bertolucci without the heights of Parma, Pasolini without the landscapes of Friuli and then Rome, Mario Luzi without the Florentine and Sienese lands?”

Over time, the naturalistic landscape opens up to human presence, traditions, folklore, and the documentation of events that by different ways have directed the evolution of our landscape: the Messina earthquake of 1908(The Duomo destroyed by the Calabrian-Sicilian earthquake - Messina 1908 by Wilhelm von Gloeden), as well as the growth of the suburbs(Via Teulié - Milan 1939/1940 by Alberto Lattuada).

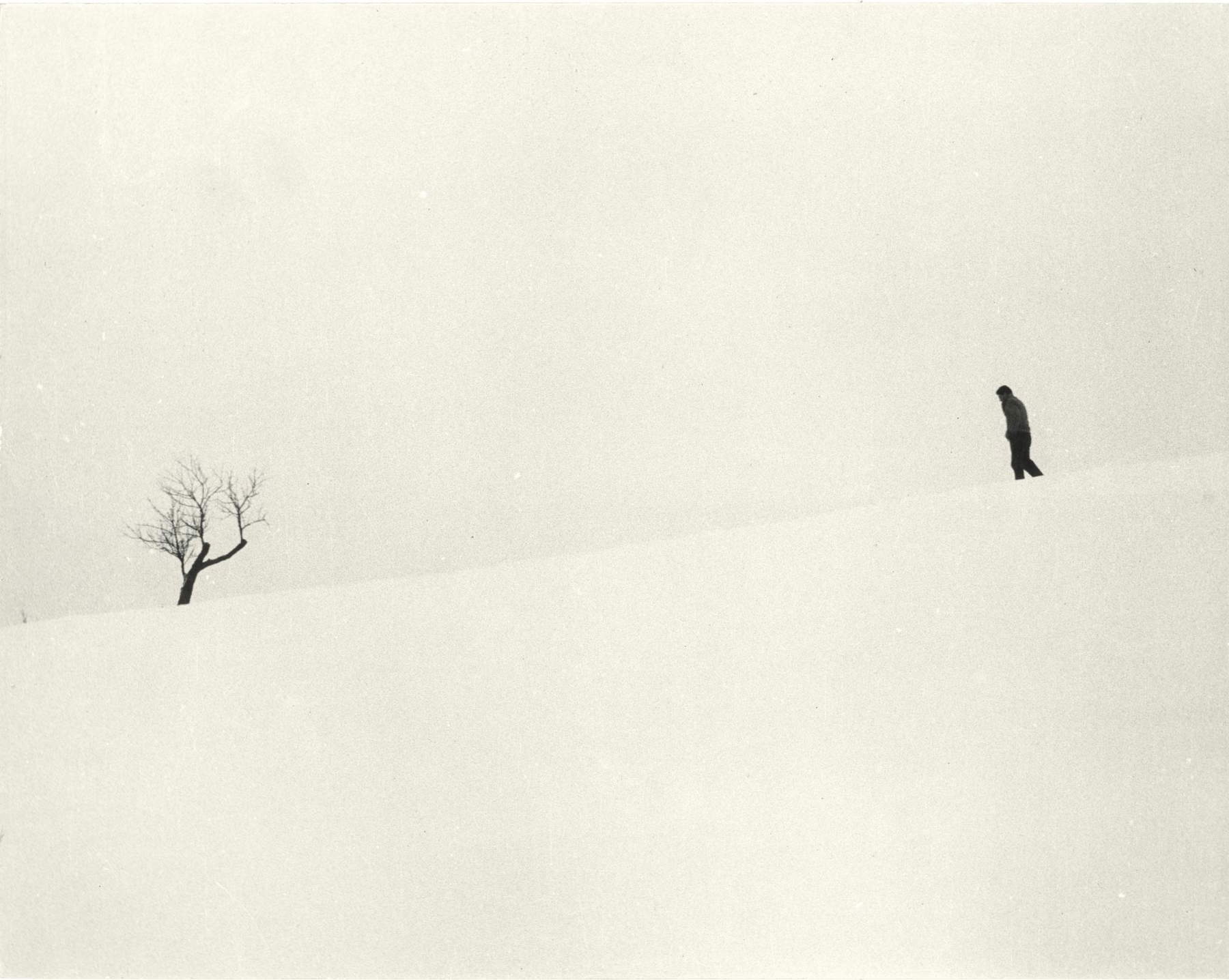

From the postwar period, the landscape becomes social and political. The room that marks the beginning of the Mufoco Collection also represents a change in perspective: humanity intercepts the lens and fills the image. These are the years of reportage, and here the photos on the Mafia by Letizia Battaglia and those on political struggles by Uliano Lucas are masterfully juxtaposed, as if they were a narrative unity, as well as Gianni Berengo Gardin’s calm account of the suburbs. One step leads to the conceptual experiments of the 1970s by Mario Cresci of Franco Fontana up to the series Presa di coscienza sulla natura made between 1976 and 1989 by Mario Giacomelli who, like no other, transformed the landscape into a unique and unrepeatable language.

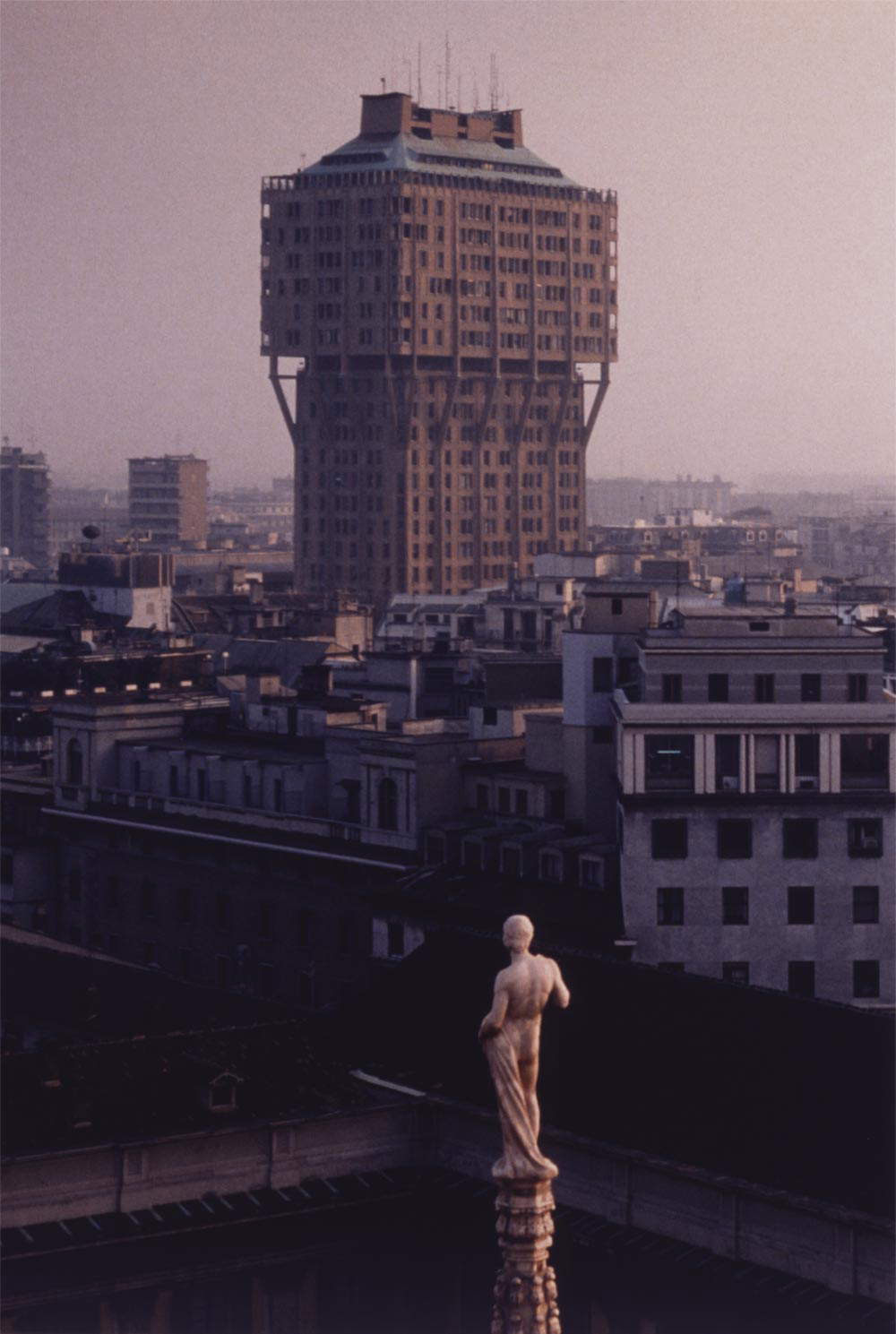

At this point the narrative path focuses on Luigi Ghirri’s Viaggio in Italia project, which in 1984 gathered together a series of visual researches that had developed in different places around the country. It was a kind of precursor to today’s exhibition at the Scuderie: a reflection on landscape made at the height of experimentation with photographic language that brought together works by twenty photographers, including Olivo Barbieri, Gabriele Basilico, Mario Cresci, Mimmo Jodice, and Claude Nori. In large strides along the exhibition we come to the new millennium, with spectacular large prints that recount the new landscapes, those of the metropolis, which are then the transformation of those same cities recounted in the years of emigration or further back in the era when nature was the protagonist. The suburbs are now under construction, as in Giovanni Chiaramonte’s series Attraverso la pianura of 1987, or constructed and spectacularly constructed as in Luca Campigotto’s Milano of 2014 or in Olivo Barbieri’s site specific_Milano 09 of 2009.

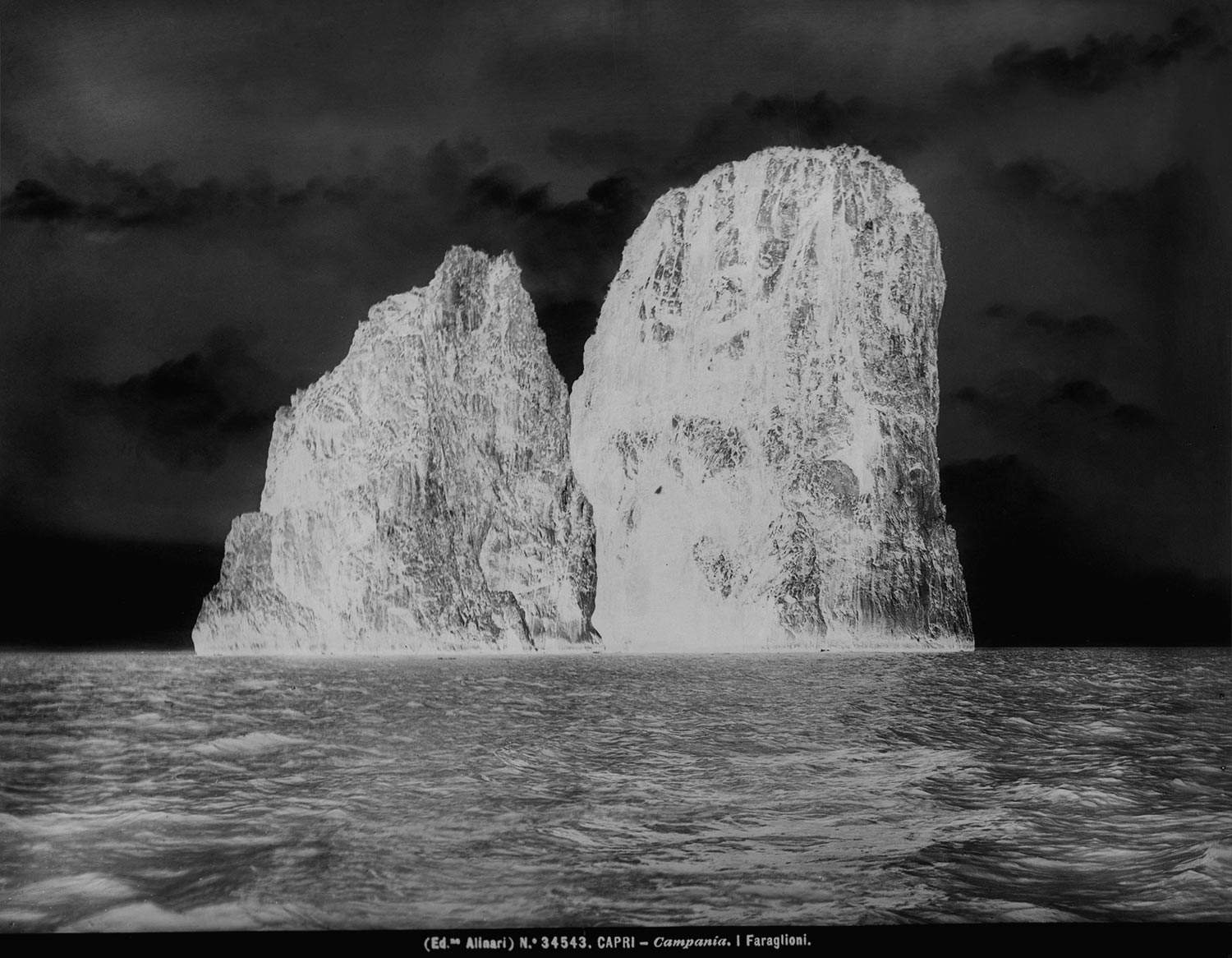

After all, at this point each image carries with it all the past that the exhibition has told us, and the works begin to return the history they have absorbed. The Faraglioni of Capri are the protagonists of Francesco Jodice’s experiments in Capri, The Diefenbach Chronicles of 2013, but also of an image by Fratelli Alinari pre-1915-the same one used in the public communication of the exhibition-that in its being displayed in negative becomes a kind of contemporary experimentation. And if you look closely, stacks are dotted throughout the exhibition, almost as if they were Thumbelina crumbs left for the visitor.

“Desire for Italy or Italy as Desire,” say the curators, “intends to detect the ongoing tension between an extraordinary past, which has seen in the Italian landscape an exceptional coincidence of nature and culture-in which we still feel we recognize our roots- and a more recent history, marked by rips, wild accelerations, aggressive interventions, dictated by economic development and globalization, which make the landscape complex and urge us to define a new Italian cultural identity.”

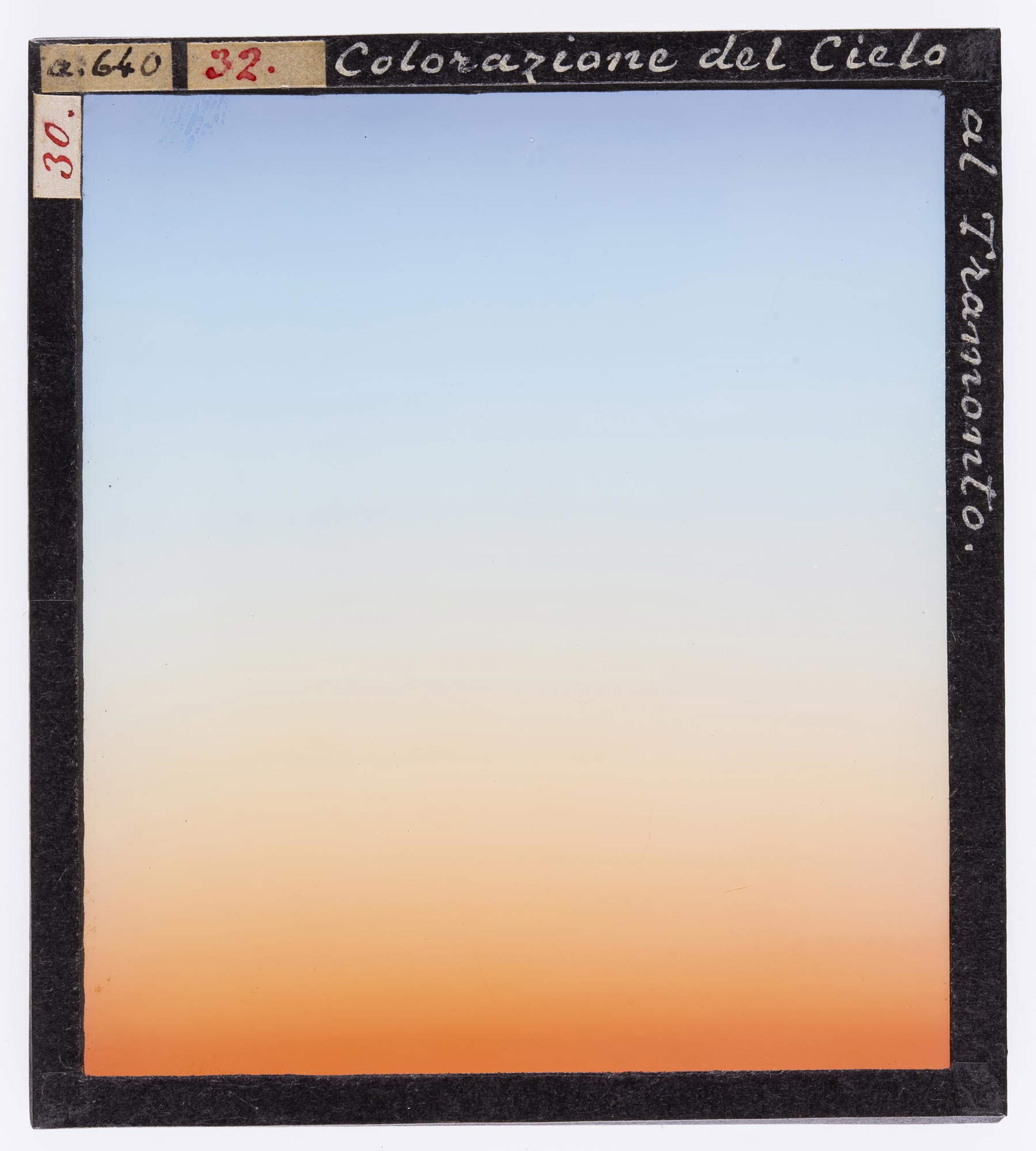

Then there is a third reading of the exhibition, which I associate with a leading awareness: that it is a narrative - inorganic but also very rich - about the evolution of the language of photography. Throughout its history, photography has not ceased to be experimental. If in the early years research was focused on technique, then it shifted to language, but in any case photographic art has never stopped evolving. And in this exhibition we can find all the traces of this history. In the early years photographers were not yet artists, but scientists, such as Giorgio Roster, who as early as 1872 offered “Slides on hand-colored glass plate.” These are images that are surprising because of the contemporary look, the 1:1 cut to which Instagram has now accustomed us, and the juxtaposition of colors that seems bold in an age we know in black and white.

Those who are passionate about photographic technique in this exhibition will find a wide variety of examples: daguerreotypes, primordial paper and glass negatives, slides, plates, autochromes, vintage prints and fine art prints from original negatives, up to large format color prints and more contemporary ways of presenting images. There are also incredible albums such as James Graham’s Italy with 131 photos made between 1858 and 1862 and printed on albumen then combined into a single album. Today we would call it a photobook.

While technological evolution in recent decades has extended the potential of the photographic medium indefinitely, and research has shifted to language, there are linguistically contemporary works even among the oldest. So of the beautiful images it becomes incredible if you read the year on the caption. I urge you to look for Vittorio Alinari’s series on Sardinia made in 1914, which reveals a photographic gaze not unlike today’s, with entirely contemporary image cuts and points of view.

I like to think that the last image of the exhibition is the landscape framed between the beautiful glass windows of the Scuderie del Quirinale: a sunset that laps the rooftops of Rome, all the way to St. Peter’s. A landscape that all visitors photograph and that will end up on their cell phones or social pages extending the boundaries of this landscape narrative to infinity.

The author of this article: Silvia De Felice

Da venti anni si occupa di produzione di contenuti televisivi per Rai in ambito culturale e ha ideato Art Night, programma di documentari d'arte di Rai 5. L'arte e la cultura in tutte le sue forme la appassionano, ma tra le pagine di Finestre sull'Arte può confessare il suo debole per la fotografia.Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.