by Federico Giannini (Instagram: @federicogiannini1), published on 01/09/2017

Categories: Exhibition reviews

/ Disclaimer

Review of the exhibition 'Labyrinths of the Heart. Giorgione and the Seasons of Feeling between Venice and Rome' in Rome, Palazzo Venezia, until September 17, 2017.

“To love without bitterness is not possible,” sentenced Perottino, the unhappy lover protagonist of the first book of Pietro Bembo’s Asolani, a treatise in the form of a dialogue on love, composed between 1497 and 1502 and published in 1505: it was a considerable success in the intellectual circles of early 16th-century Venice, and large hosts of art historians did their utmost to investigate to what extent the influence of the Asolani had extended into the field of visual arts. This love, which, according to the disconsolate Perottino, cannot exist without at the same time experiencing bitterness (so much so that the character traced the etymology of the term precisely to the adjective “bitter.” love “null’altro ha in sé e nelle sue operationi che amaro, da questa parola, sì come io mi credo, assai acconciamente così detto da chiunque si fu chi il quale prima questo nome gli dareè”), would be according to many the main protagonist of the painting by Giorgione (Castelfranco Veneto, 1477 - Venice, 1510) known as the Two Friends, a work around which the entire exhibition Labyrinths of the Heart revolves. Giorgione and the Seasons of Feeling between Venice and Rome, aimed at investigating the representation of feelings (and with it the links that, in that context, united art to music and literature: an example has just been given) in painting at the beginning of the 16th century, notably that produced in the Venetian sphere.

A hundred objects including paintings, sculptures, prints, manuscripts and documents: such is the base that concurs to give substance to the exhibition, one of the main exhibition events held in 2017 in Rome. It is an excellent exhibition that is distinctly informative (albeit with some flaws), curated by a great expert on Venetian art and Giorgione such as Enrico Maria Dal Pozzolo, and divided between two museums, the Museo Nazionale di Palazzo Venezia and that of Castel Sant’Angelo, which offer two different paths, brought together in a substantially unified discourse, so much so that one struggles a bit to follow the second section, that of Castel Sant’Angelo, if one has not visited the first, which serves as a guide and context. Perhaps one should also question theappropriateness of extending the itinerary to Castel Sant’Angelo, a place that has little to do with the exhibition’s themes (were it not for the fact that, to get to the rooms in which the exhibition is held, it is necessary to traverse the entire path of the museum a “labyrinth” in keeping with the title of the exhibition) and whose often cramped spaces (the itinerary was set up in the papal apartments) do not make it very easy to enjoy, even taking into account the fact that Castel Sant’Angelo is, taken out of the Roman Forum and Colosseum circuit, by far the most visited museum in Rome, with over a million visitors a year. One wonders, therefore, whether it would not have been better to condense the itinerary and have the entire exhibition held at Palazzo Venezia(or, rather, at the Palazzo di Venezia). Not least because the exhibition opens with a long (and perhaps unhelpful) introduction on the history of the palace.

The visitor, for three rooms, is informed about the events that led to the donation of the palace to the Venetian Republic, about the relations between Venice and Rome in the 16th century (admittedly resolved in a decidedly superficial way: nothing more than two allegories and two views), and about the vicissitudes of a couple of the owners of the building, namely Pietro Barbo and Domenico Grimani, whose presence in the exhibition is motivated by the fact that the two would have fostered cultural exchanges between Rome and Venice. For Domenico Grimani, then, another detail is added: the Venetian cardinal was a passionate collector, and his collection included works by Giorgione. The exhibition goes so far as to assert that because Domenico Grimani was a collector of Giorgione, the painter may have “passed through” the rooms of Palazzo Venezia: it is true that, to the writer’s memory, the hypotheses of a Giorgione trip to Rome date back to at least the 1950s, but the bases on which these hypotheses are founded are broader than the mere presence of works by the artist in Domenico Grimani’s collection, and they also involve that Giorgione-like classicism that represents one of the most important nodes in the production of the painter from Castelfranco. The issue emerges in all its importance from some works that may have taken more than one cue from ancient marbles present in the cardinal’s collection: one thinks, in particular, of the two panels conserved in the Uffizi, not present in the exhibition, and to which the so-called Homage to a Poet, one of the three paintings attributed to Giorgione that are instead present at Palazzo Venezia, has long been linked. In all three cases, however, there have been those who have questioned this attribution, but the exhibition is very clear in specifying that we have no certainty as to the author of the works, and this is especially true of the Two Friends. On the other hand, with regard to the so-called Homage to the Poet, which Dal Pozzolo assigns to the artist’s early production, it is pointed out that the work at Palazzo Venezia is identified as Phaeton before Apollo, a subject recently proposed in scholarly circles and presented here for the first time in an exhibition context. The other small Giorgionesque tablet with Leda and the swan, on loan from the Civic Museums of Padua, also fits coherently into the discourse: the subject is derived from that Cygnus concubans cum Leda, the ancient cameo now in the National Archaeological Museum in Naples, which in 1457 appeared in an inventory of Pietro Barbo’s collection.

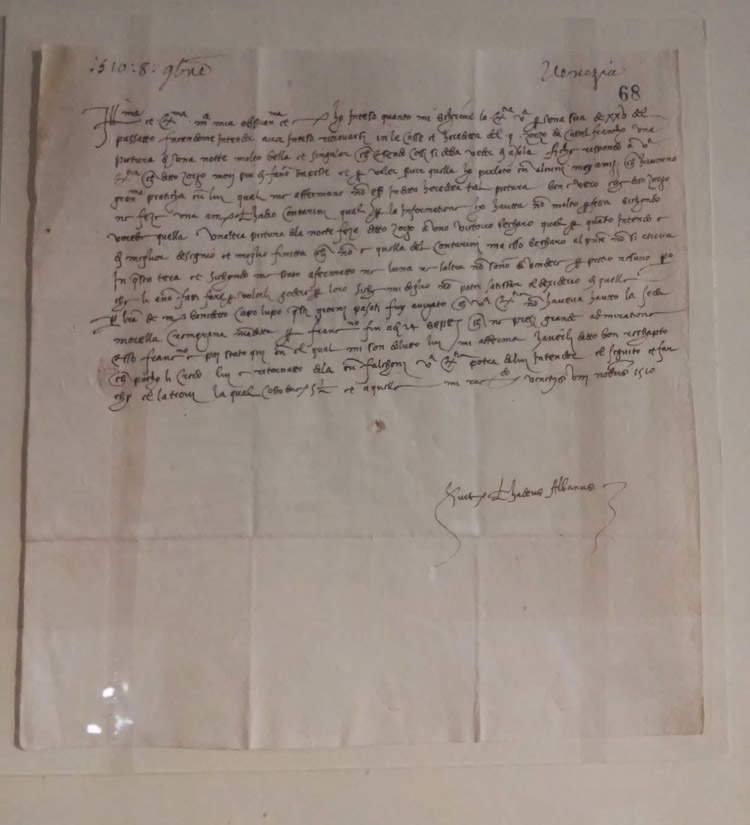

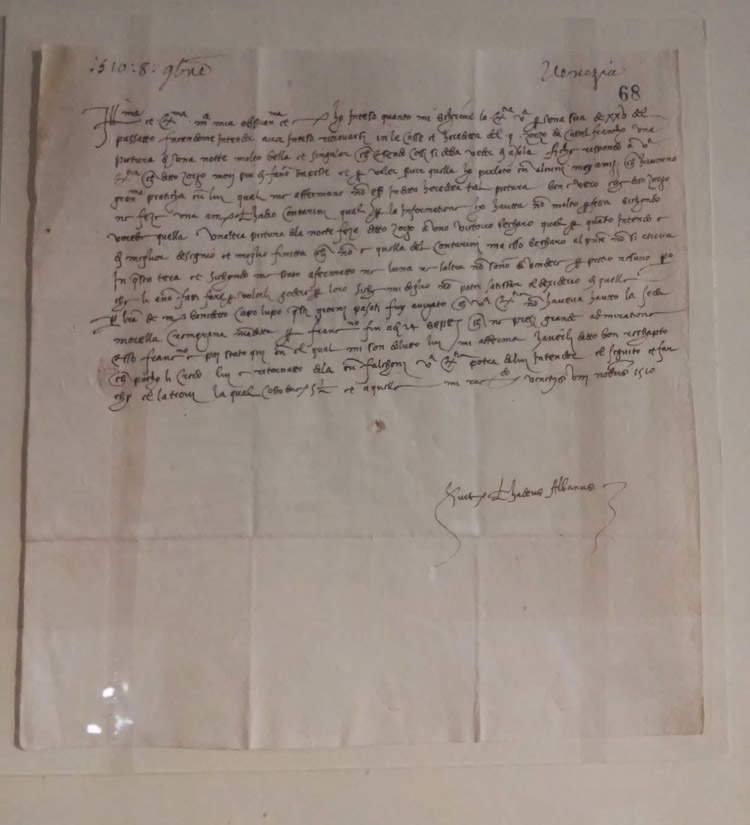

In the same room, the fourth, which aims to present to the public the elusive figure of Giorgione and, by extension, his relations with Rome, three of the very few documents concerning the activity of the Venetian artist are collected: in particular, we have the famous letter in which Isabella d’Este asks Taddeo Albano, her agent in Venice, for enlightenment about a painting by Giorgione, then we have Albano’s reply to the marquise of Mantua, informing her of the painter’s disappearance and the fact that the painting she requested does not exist, and finally we have theinventory of the property found in Giorgione’s house.

|

| One of the rooms (at Palazzo Venezia) of the exhibition Labyrinths of the Heart. Giorgione and the Seasons of Feeling between Venice and Rome. |

|

| Giorgione, Phaethon before Apollo (c. 1496-98; oil on panel, 59 x 48 cm; London, The National Gallery) |

|

| Giorgione, Leda and the Swan (1499-1500; oil on panel, 12 x 19 cm; Padua, Musei Civici, Museo dArte Medioevale e Moderna) |

|

| Letter from Taddeo Albano to Isabella d’Este (Venice, November 8, 1510; dark sepia ink on paper, 23.1 x 22 mm; Mantua, State Archives, AG, b. 1893, c. 68) |

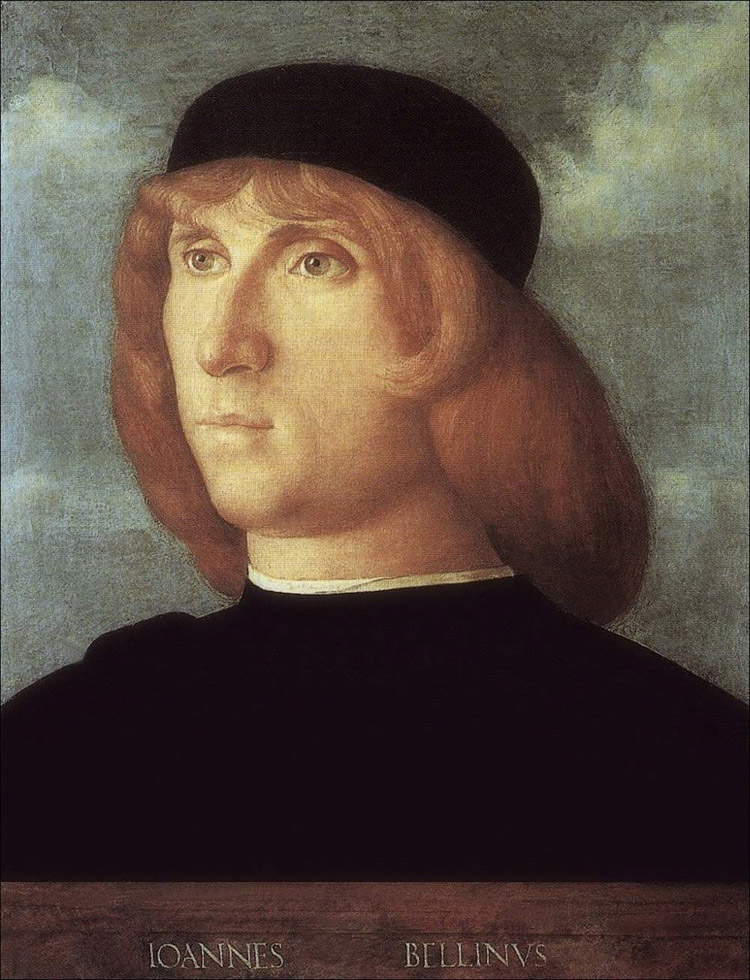

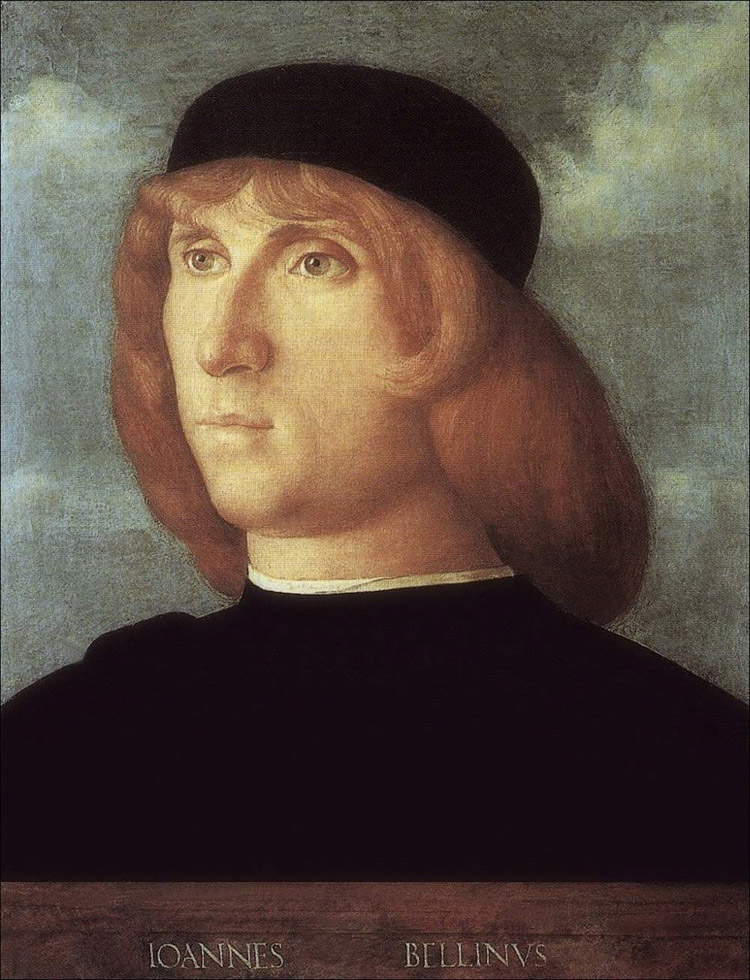

The portrait of the Two Friends is arrived at in stages. In fact, the curator’s problem is how the author of the painting came to elaborate such a peculiar theme, if we consider the fact that, at the time, the portrait genre was not used to make explicit a sentimental situation, but rather to give an account of a status achieved or to preserve the memory of the person portrayed. There is a shift, in essence, from emphasizing exteriority to investigating interiority. With the Two Friends, Dal Pozzolo assures us, we are faced with the first, highly original example of a new genre that finds its premises in Venetian portraiture of the second half of the fifteenth century, that of Antonello da Messina, Giovanni Bellini, his brother Gentile, Marco Basaiti, and Giovanni Cariani. Specifically, there is a more pointed desire to capture theindividuality of the subject, the traits that make him or her unique, even within the substantial gravity that characterizes the protagonists of such portraits. These specifics, demonstrated at Palazzo Venezia by some splendid portraits, starting with the two portraits of men by Gentile and Giovanni Bellini and continuing with the double portrait by Marco Basaiti (in which, however, the characters appear more juxtaposed than united by a real and solid psychological bond), are necessary premises for arriving at thepsychological investigation andautonomous rendering of the characters’feelings, whose state of mind is also probed through the literary sources of the time.

This is what was said at the beginning: the protagonist of Two Friends is in fact an unhappy love that torments the young man in the foreground, who holds in his hands abitter orange (a melangolo, as they used to say at the time) that symbolizes the sweet appearance of love which, exactly like the melangolo, nevertheless conceals a bitter heart. Painting that therefore implies a suffering on the part of the protagonist, who pines for the pains of love and seems indifferent to the friend placed further back, who, on the other hand, is not at all moved by the same feelings as the young man in the foreground and could therefore signify, allegorically, the steadfastness of the man who does not let himself be disturbed by earthly things, or simply the rationality little inclined to romanticism: what is certain is that, in front of this portrait, we are not only in the presence of two different (indeed: opposites), but we also glimpse a reflection of the culture of the time, which celebrated love with prose, lyrics, and musical compositions, and Giorgione (or whoever) seizes the stimuli coming from such cultural circles to produce an extremely evocative painting, which draws on Bembo’s Asolani, as suggested in the opening, but also, for this way of understanding the torment of love as a pain on which to meditate in silence and in one’s own intimacy rather than as a plague of which to complain openly, to Petrarch’s Canzoniere, another collection particularly appreciated at the time (it is worth noting that two early sixteenth-century printed editions of Bembo’s Asolani and Petrarch’s sonnets are present in the exhibition). Finally, a painting that demonstrates a sensitivity and capacity for psychological introspection that stand out from the ordinary.

|

| Giovanni Bellini, Portrait of a Man (c. 1490-95; oil on panel, 34 x 26.5 cm; Rome, Capitoline Museums) |

|

| Marco Basaiti, Double Portrait (c. 1500; oil on panel, 24.5 x 19.5 cm; Rome, Galleria Nazionale dArte Antica di Palazzo Barberini) |

|

| Giorgione, The Two Friends (c. 1502; oil on canvas, 77 x 66.5 cm; Rome, Museo Nazionale di Palazzo Venezia) |

After a look at Luca Brinchi and Daniele Spanò’s videomapping “The Garden of Dreams” (an “immersive video sound installation,” the authors clarify), which in the Sala delle Battaglie, in a cool room with comfortable chairs, closes the Palazzo Venezia section, one can embark on a half-hour walk to Castel Sant’Angelo: Having somehow overcome the inevitable crush and traversed, as mentioned, the entire museum route, one arrives at the Papal Apartments, where the second part of the exhibition(The Seasons of Sentiment between Venice and Rome) is organized by macro-themes and opens where Palazzo Venezia had left us, namely from the literary reflections on the theme of love: printed editions of Petrarch’s sonnets, Boccaccio’s Decameron, and then treatises by Bembo, Lodovico Dolce, Mario Equicola, Francesco Barbaro and others accompany the visitor in a sort of introduction to which is entrusted the task of letting the public know that love was one of the main concerns of the cultural circles of the time. Without wishing to go into the merits of the individual thematic rooms (they range from music to labyrinths, from love symbols to seduction), we would like to focus on some of the main works in the second part of the exhibition, starting with a Lady with Carnation by Giomo del Sodoma: in ancient times it was customary to exchange such a flower to seal an engagement, and the canvas is functional in emphasizing the role of the symbol in explicating a loving feeling. Carnations then, but also gloves, letters, assorted plants: the sampler on display is discreetly large. “From words and symbols to deeds,” then suggests the panel of the immediately following thematic group, devoted to seduction: in a slightly secluded niche (almost as if it were an alcove: the setting thus becomes somewhat consistent with the subject matter) find space for certain nudes of great procaciousness, but also portraits of wives uncovering their breasts as a sign of fidelity, since showing such a part of the body meant offering one’s heart, as explained by the erudite Giovanni Bonifacio in his treatise Arte de’ cenni, a print of which from 1616 is exhibited in Castel Sant’Angelo, open to the very page of our interest (“the opening of the cloths in front of the breast will be a gesture of wanting to show the heart and so of reality and sincerity”). Belonging to the latter is Bernardino Licinio’s Portrait of a Woman Uncovering Her Breasts, which in all probability depicts the painter’s sister-in-law (identification is possible thanks to other works in which we know for a fact that her brother Arrigo’s wife appears), while decidedly more seductive is Girolamo Siciolante da Sermoneta’s Nuda, which offers herself without any veil to the observer, inviting him to join her with gestures that are not even too cryptic.

A very prominent role is played by Bartolomeo Veneto’s famous Portrait of a Gentleman, which came to Rome from the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge. This portrait is famous because the gentleman, on his chest, bears that labyrinth that gives the exhibition this somewhat romance novel title, and which is interpreted as a symbol of the labyrinth of feelings that each of us carries within us. It should be specified that in reality there has never been an unambiguous interpretation of the Cambridge portrait: very fitting, for example, is the one that understands the labyrinth as an allegory of the deceptions of the world, which tempt theman of faith. All the more so since the form recalls that of the labyrinth that adorns the floor of Chartres Cathedral (labyrinths are often encountered in French churches: this detail, combined with the typically Burgundian style of the headdress, should leave no doubt as to the nationality of the subject depicted) and the theme is related to the well-known religious disputes that shook Europe at the dawn of the 16th century and beyond. However, the interpretation provided in the exhibition is also suggestive, strengthened by the fact that the man on his hat has a pin with a cameo depicting a shipwreck and that he is touching the pommel of a sword with his hand, as if he is about to prepare for battle.

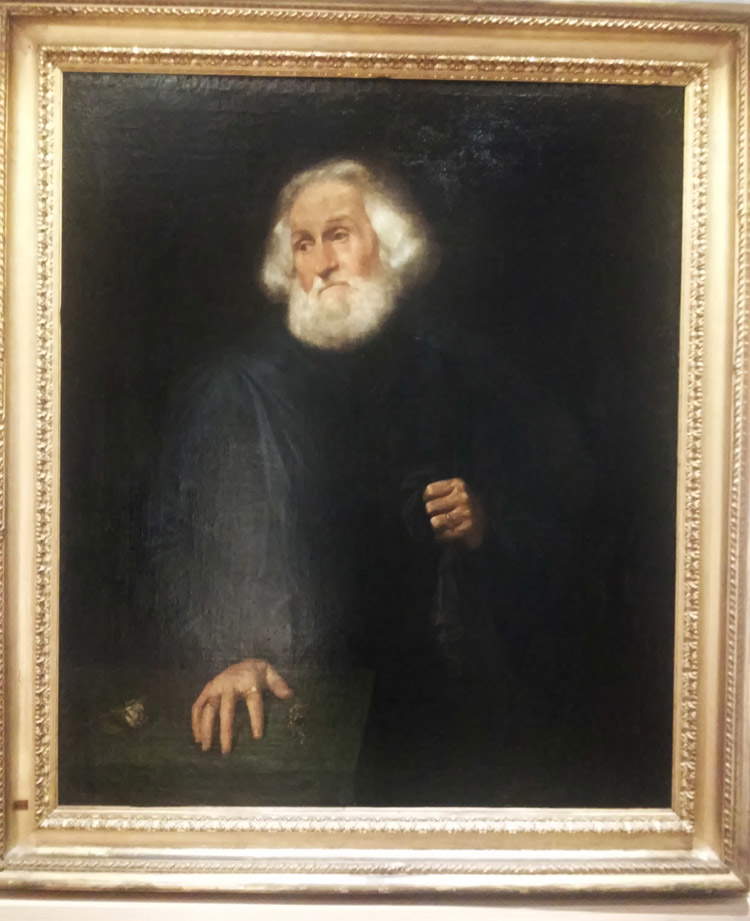

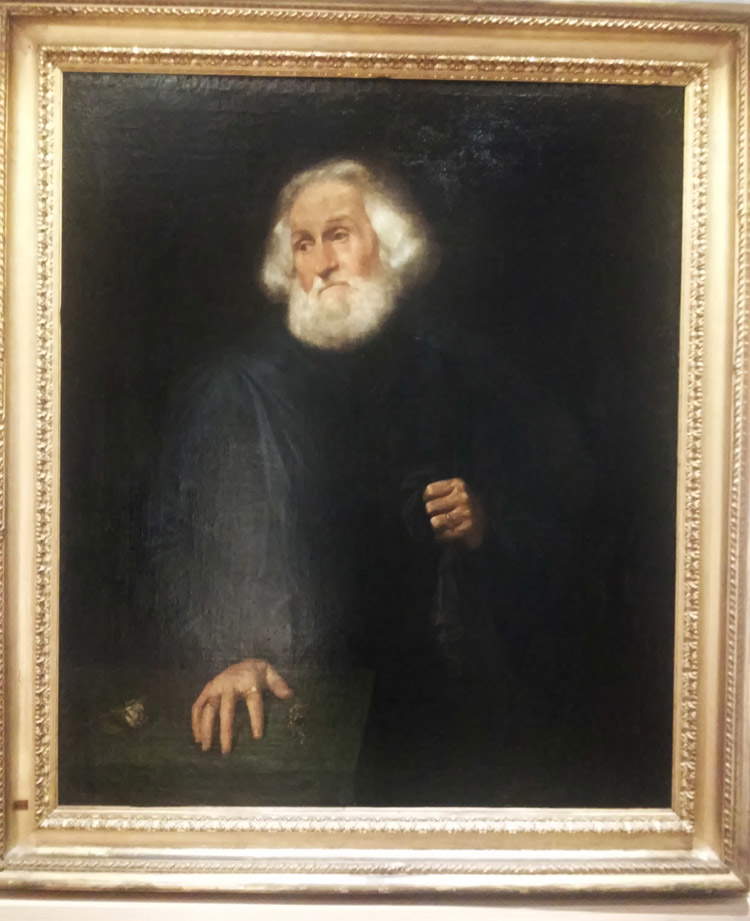

As the exhibition draws to a close, it begins to get a little lost: there is a section devoted to embraces as symbols of union, especially in the family sphere, in which a Portrait of Arrigo Licinio’s family stands out, painted by the aforementioned Bernardino, who at the time specialized in group portraits (and this is one of the highest examples: moreover, in the work, we find the sister-in-law we had already met in the group devoted to seduction). There is a section dedicated to Francesco I de’ Medici, justified on the basis of the disinterested love that the Grand Duke of Tuscany had for the Venetian Bianca Cappello: however, in an itinerary dedicated to Venetian art of the early 16th century, this “deviation” seems completely out of time and out of place. Closing the exhibition, finally, are the paintings dedicated to memoirs. Figure a Portrait of an Old Man of ancient and no longer accepted Giorgionesque attribution (a portrait of a widower: the memory is that of the bride whose absence fills the character’s eyes with melancholy), but the protagonist is still Bernardino Licinio, who ends the itinerary with a Lady holding a portrait of a male figure: almost certainly a bride holding the portrait of her absent husband. We do not know the reasons for this distance: certain is that this woman’s love is so strong that it leads her to embrace and caress, with a gaze veiled in brooding sadness, the image of her man.

|

| A moment from the screening The Garden of Dreams |

|

| Giomo del Sodoma, Lady with Carnation (c. 1540-50; oil on panel, 61 x 43.5 cm; Siena, Accademia Chigiana) |

|

| Bernardino Licinio, Portrait of a Woman Discovering a Breast (1536; oil on canvas, 83 x 69 cm; Bergamo, private collection) |

|

| Girolamo Siciolante da Sermoneta, Nude (c. 1548; oil on canvas, 190 x 93 cm; Rome, Capitoline Museums) |

|

| Bartolomeo Veneto, Portrait of a Gentleman (c. 1510-15; oil on panel, 72.8 x 54.3 cm; Cambridge, Fitzwilliam Museum) |

|

| Bernardino Licinio, Portrait of the Family of Arrigo Licinio (1535-40; oil on canvas, 118 x 165 cm; Rome, Galleria Borghese) |

|

| 15th-century Venetian painter (formerly attributed to Giorgione), Portrait of an Old Man (1530-40?; oil on canvas, 107 x 90 cm; Rome, Galleria Doria Pamphilj) |

|

| Bernardino Licinio, Lady Holding a Portrait of a Male Figure (1525-30; oil on canvas, 77.5 x 91.5 cm; Milan, Pinacoteca del Castello Sforzesco) |

Coming out of Labyrinths of the Heart. Giorgione and the Seasons of Feeling between Venice and Rome, one has the feeling of having had to deal with an opportunity that could certainly have been better exploited: certain curatorial choices that seem forced, the division between two exhibition spaces that risks losing the thread of the discourse, some solutions that frankly need to be revised in the exhibition design (such as certain captions that are located about ten centimeters above the ground, and moreover in dark rooms), are details that can certainly be improved. But summing up, one can safely assert that the exhibition is an overall good operation, and several positive aspects are: an itinerary that is certainly well thought out, works that are often surprising, an exhibition that succeeds in projecting the public into the atmospheres of the early sixteenth century, a popular slant that is as suitable as ever for a heterogeneous audience, the appreciable desire not to do an exhibition on Giorgione (just seven years after the great monographic exhibition in Castelfranco Veneto, with no particularly important novelties, would not have been the case at all), but to make the great artist from Castelfranco the protagonist of an exhibition that, moreover, could open interesting lines of research on the relationship between art and feelings in the early 16th century Veneto. This, at least, is the curator’s hope. Finally, special praise is due to the exhibition’s ability to keep the visitor’s interest constantly alive through a fascinating narrative punctuated by clear and strong illustrative panels with an almost colloquial language: details that should not be taken for granted and that infuse the exhibition with a freshness not always found in exhibitions of ancient art.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools.

We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can

find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.