Article originally published on culturainrivera.it

Among the most interesting exhibition events of the summer (and dare I add “nationally”) one cannot but include the exhibition that CAMeC in Spezia dedicates to the seminal figure of Giulio Turcato (Mantua, 1912 - Rome, 1995), one of the most representative painters of the 20th century in Italy. Giulio Turcato. Dalla forma poetica alla pittura di superficie (thus the title) is not only an exhibition of contemporary art (but by now codified to such an extent that one can safely speak of art history): it is a history of freedom, because Giulio Turcato was one of the freest and least tame of those working from the 1950s onward. And it is precisely this extreme freedom that seems to constitute the main leitmotif on which the exhibition wants to insist, which broadly traces Turcato’s entire artistic career, starting with the works of the 1940s and ending with his latest research.

|

| Giulio Turcato. From poetic form to surface painting |

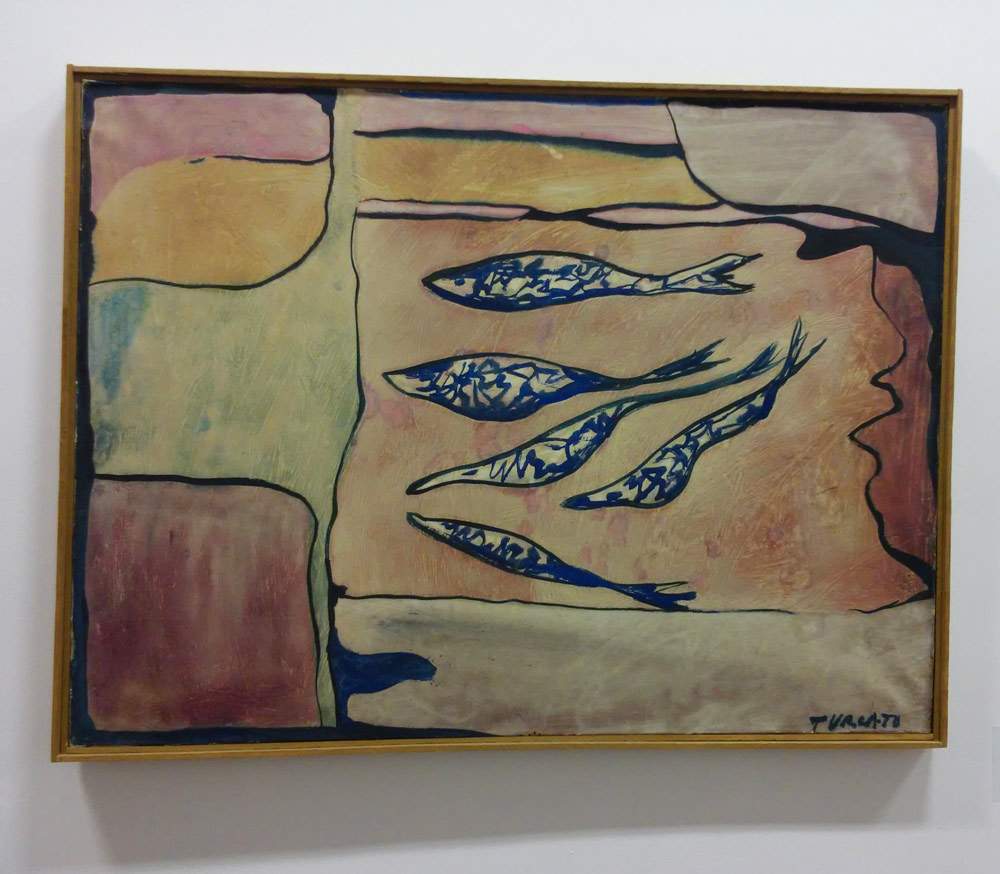

The early years, those in which Turcato first militated in the Forma 1 group, then in the Fronte Nuovo delle Arti and then broke away from it to join, in 1952, the so-called Group of Eight, are summarized in some works that the visitor finds in the first room: they are works in which the adherence to the natural datum is still completely evident, although the painter’s sensibility already appears to be oriented toward original forms that would be deepened in the years to come. This is the case with some works that still show Cubist references but already begin to open up to other experiences, such as that of Kandinsky, towards whom, starting in 1947, the year of his stay in Paris, Turcato will begin to feel a sincere admiration: thus we have a Still Life with Fish of 1945, from a private collection in Milan, and above all the Shipyard of 1951, a fundamental work for several reasons. The first: it is a work that inextricably binds the artist to the city hosting the exhibition, because with this work the artist won the National Painting Prize “Golfo della Spezia,” and because it is one of the two canvases kept in the permanent collection of CAMeC. The second: it is certainly the work in the exhibition that best testifies to Giulio Turcato’ssocial commitment at this stage of his activity (his most famous work in this sense, the well-known Comizio, is unfortunately not in the exhibition).

|

| Giulio Turcato, “Still Life with Fish” (1945; oil on canvas, 60 x 80 cm; Milan, private collection) |

|

| Giulio Turcato, “Cantiere” (1951; oil on canvas; La Spezia, CAMeC) |

Giulio Turcato in fact is a staunch communist, but he is certainly not a communist who has the line imposed on him: this becomes especially evident at the moment when the break between the figurative and abstract painters who constituted the Fronte Nuovo delle Arti was consummated. The PCI rejectsabstract art, deeming it ill-suited to the needs of the party, of whose demands, according to Togliatti, a realistic and immediate art would be better bearers. Turcato, however, accorded more importance to his own sensibility rather than to the party’s guidelines, so he joined, as anticipated, the “Group of Eight,” which was born precisely at the behest of a handful of artists who thought like Turcato, and continued his research, which veered definitively toward an eclectic and versatile abstractionism. In the words of Lionello Venturi, “his nature as an artist prevailed.”

Not that his connections with reality (and also with political engagement) disappeared overnight: this is evidenced by a work such as The Garden of Micurin from 1953, whose title refers to the figure of the Russian (and later Soviet) botanist Ivan Vladimirovic Micurin, who worked to create varieties of plants resistant to Russia’s harsh climatic conditions, an effort that earned him recognition from the regime (which even changed the toponymy of a city in his honor). In the painting, which belongs to an entire series on the same subject (this one, from a private collection in Milan, is the only one exhibited in La Spezia), black weaves evoke the branches of plants while variously colored figures suggest to us an idea, precisely, of the colors of flowers and fruits produced by the plants studied by Micurin.

|

| Giulio Turcato, “Micurin’s Garden” (1953; oil on canvas, 66.5 x 80 cm; Milan, private collection) |

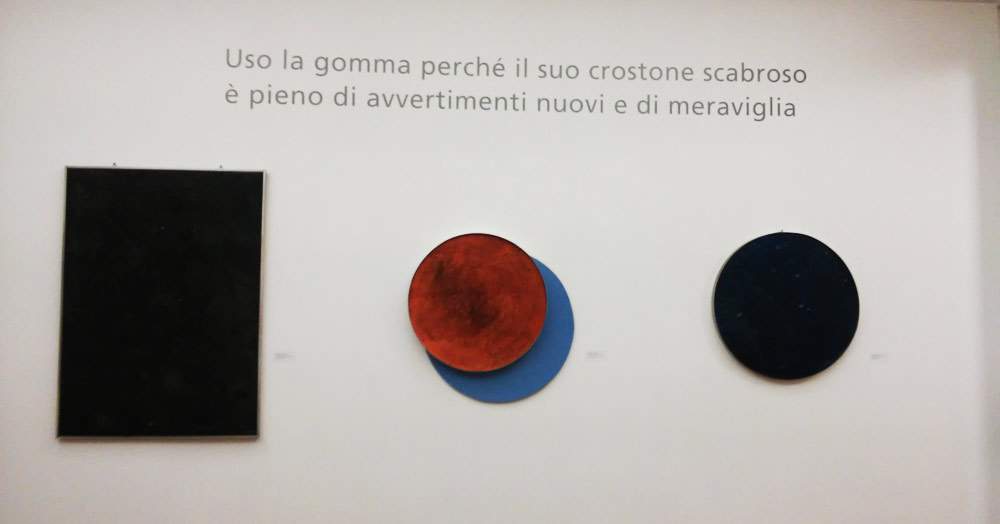

The innovative charge of Giulio Turcato’s art knows further evolutions dictated, in all probability, by the suggestions that the Spatialist artists but also, in a certain sense, the nouveaux réalistes could provide him with: works such as the Tranquillanti and the Superfici can be explained in this sense, of which the visitor can find several examples at CAMeC. These are researches that originated in the late 1950s but lasted throughout the following decade. With the Tranquillanti, the artist pastes real tranquilizer tablets onto monochrome surfaces: since the use of tranquilizers is widespread, the artist thinks, no one will object if you use them to create a work of art. The real object enters the artwork to evoke certain situations to the viewer, helped also by the almost always dark, nocturnal tones of the background. The Surfaces continue this search for new expressive possibilities: the material itself becomes a work of art capable of expression and evocation, as happens in the Lunar Surfaces, where the roughness, holes and cracks of foam rubber, one of Turcato’s favorite materials at this stage, suggest the craters and seas of the Moon. “I experiment to be able to move the limit of possible expression a little further,” Turcato says in an interview dated 1982, “to dilate language. It is necessary to create an intensely psychological form, working also on the tools,” and this search for new possibilities stems from the conviction that the painting needs “to be a vehicle of meaning and communication, to reach the eye immediately,” and that it is “the whole of the painting” that has to “slap the eye.” And the choice of foam rubber, as the artist wrote in 1966 but as the lettered inscriptions on the wall displaying Lunar Surfaces at CAMeC also remind us, was born “because its rough crust is full of new warnings and wonders.”

|

| Three “Lunar Surfaces” by Giulio Turcato |

|

| Giulio Turcato, “Lunar Surface” (1968; oil and mixed media on foam rubber, diameter 90 cm; private collection) |

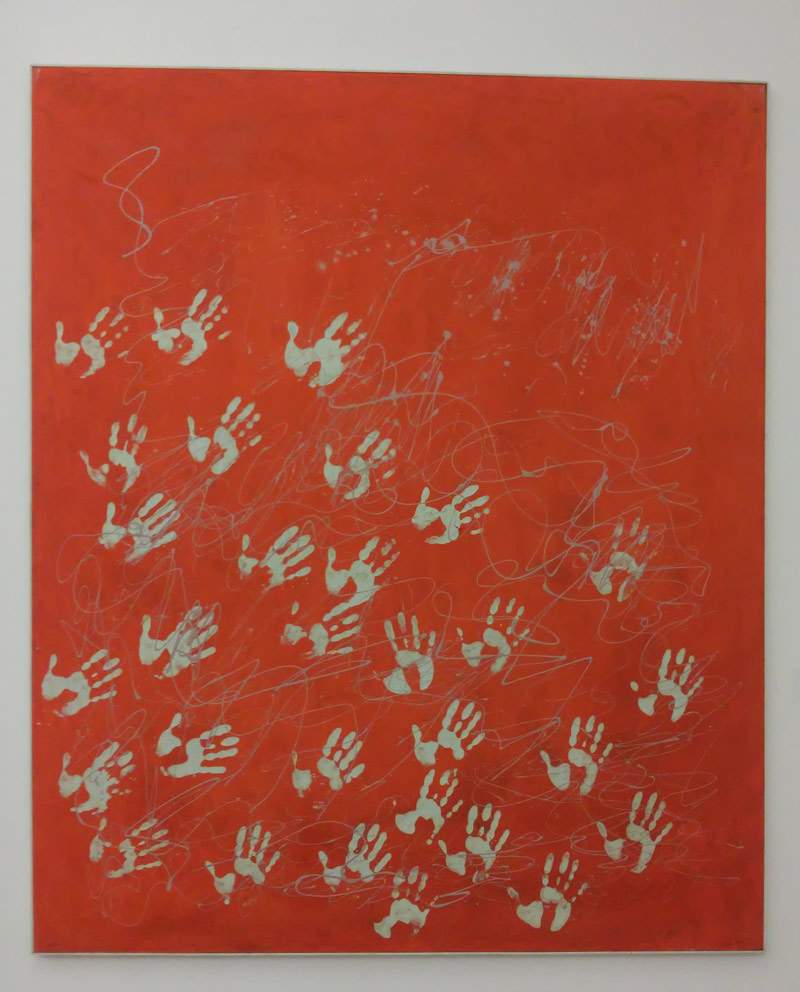

The new possibilities of expressive techniques then move to investigate not only objects and surfaces, but also forms, colors and lights. The relevance of the artist’s gesture emerges from a work such as Alleluia, where the white, curved, continuous and interlacing line, made with an abstract expressionist technique, is united with thehandprint: for an artist there is no simpler, more primitive gesture than to place a hand on a canvas, and this almost liberating gesture (hence perhaps the painting’s name) allows Turcato to “identify” himself in the work. Assumptions not far from those of the abstract expressionists themselves, with the difference that, writes critic Vito Apuleo, “Rothko’s existential anguish in Turcato becomes musical emotion.” Musical emotion also suggested by the works where the motif of these brightly colored graffiti returns, often trapping real objects: this is the case, for example, of the Lira, where the colored signs dear to Turcato create playful interlacements in complete freedom around real banknotes.

|

| Giulio Turcato, “Alleluia” (1970; oil and mixed media on canvas, 180 x 180 cm; private collection) |

The latest research, between the 1980s and the 1990s, concerns above all color and its possibilities: the Cangianti, canvases on which Giulio Turcato spreads colors by exploring combinations and tones and making his drafts perform almost a sort of harmonious dance , belong to this era (and it is no coincidence that in the last room of the exhibition, the one that houses the Cangianti, we move to a musical background designed for the occasion: a “sound installation” conceived by musician Andrea Nicoli who teaches at the conservatory in La Spezia). Color changes express mood changes, emphasize sensations, try to establish a relationship with the observer, in front of them “one can receive different signals: it depends on us if we want to move.” The conclusion of the exhibition is entrusted to two “variants” of the Cangianti theme, namely Astral Voyage and Archipelago, which fully demonstrate the aforementioned possibilities: with a single color, through various gradations, Turcato offers the possibility of taking an itinerary through space and seeing from above a set of islands emerging from a crystal clear sea.

The two curators, Eleonora Acerbi and Marzia Ratti, have been able to create a rich and complete itinerary, capable of retracing the entire career of Giulio Turcato by touching on the most important points of his artistic evolution, lingering intelligently on the most original peaks of his research, probing in depth the personality of one of the freest and most innovative artists of the 20th century in Italy. If one really wants to find a fault, one could say that, totally lacking works by other artists, the apparatus could have insisted more on the context within which Giulio Turcato worked, perhaps using a language more suitable for a general public (not everyone is expected to know, I quote from one of the introductory panels, “the orientations of Italian zdanovism” that led the painter to break with the artists of the Fronte Nuovo delle Arti more loyal to the party’s directives), and perhaps emphasizing relationships with other coeval experiences. But apart from that, Giulio Turcato ’s Visitor. From Poetic Form to Surface Painting will be pleasantly surprised by an organic exhibition capable of recounting a “protagonist of the twentieth century,” as Marzia Ratti defines him, in a pleasingly effective manner.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.